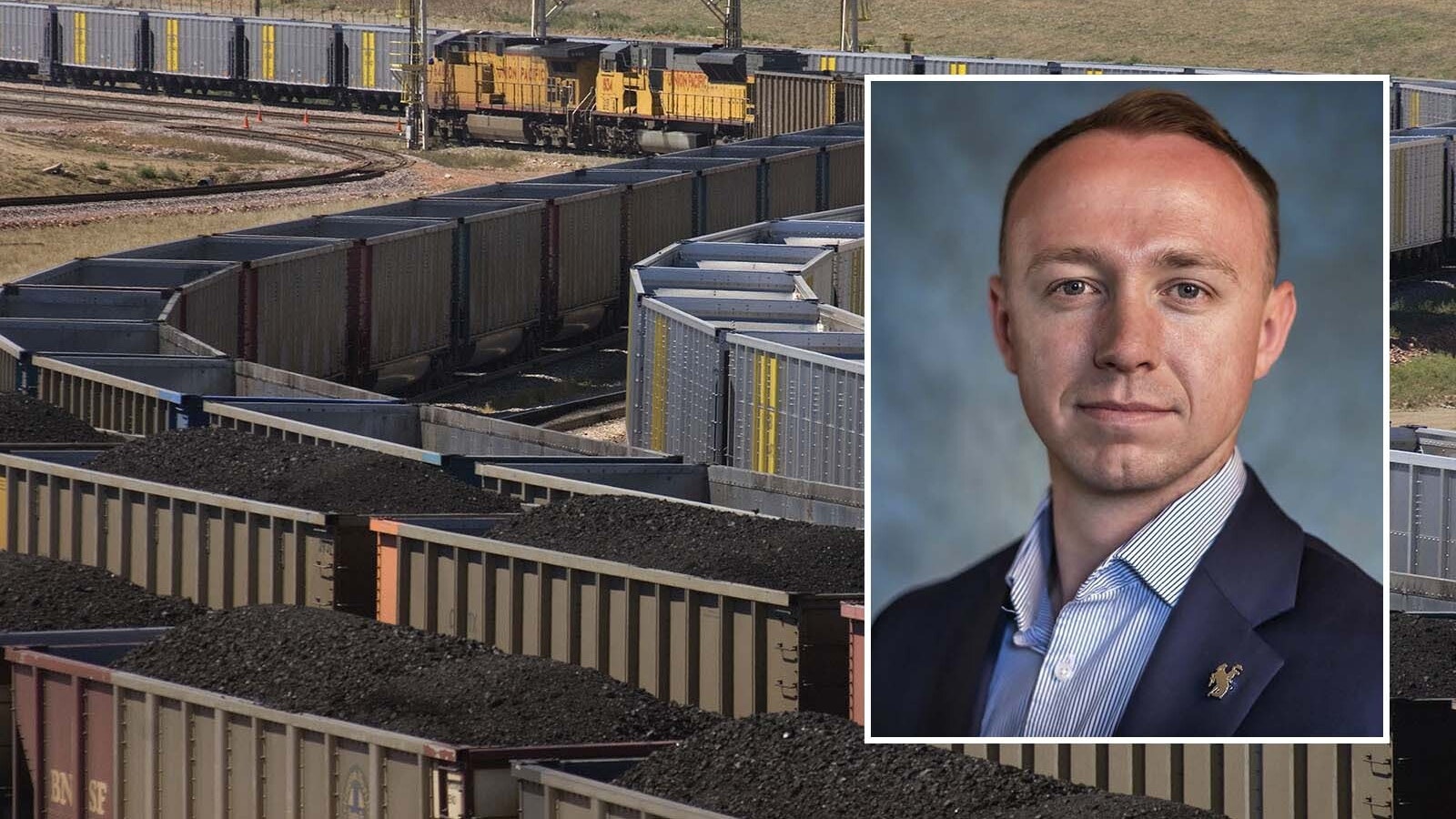

With two of Wyoming’s largest coal mines closed pending Blackjewel LLC’s bankruptcy filings and approximately 600 laid-off workers warming the bench, legislators and state economists are contemplating the future of coal in Wyoming.

“Just because a coal mine stops producing doesn’t mean the demand for coal stops,” said Dan Noble, Wyoming Department of Revenue’s director. “Because most coal-fired power plants use Powder River Basin coal, those coal customers may switch to the other producers in that area. At which point, there’s not a significant drop off of coal produced.”

Wyoming Sen. Cale Case, R-Lander, explained coal-fired power plants tune their operations to coal products from specific regions of the world.

“Another mine (in the basin) might be able to pick up (Blackjewel’s) contracts,” Case said. “While that’s a reasonable story for the tax receipts, it’s not at all good for the laid-off workers.”

As the Senate chairman of the Wyoming Legislature’s Joint Revenue Committee, he said Blackjewel’s bankruptcy was concerning, but he pointed to the larger issue: The coal industry is withering away.

“We are looking at a general reduction in production of Powder River coal,” Case said. Revenue Committee House of Representatives Chairman Rep. Dan Zwonitzer, R-Cheyenne, added coal mining in Wyoming might grind to a halt in little more than 10 years.

“The modeling used to say we’d be good until 2050,” Zwonitzer explained. “Now, the modeling is saying 2030.”

The loss would be a major hit for the state, he said.

Reviewing only severance tax, which is imposed on the extraction of non-renewable natural resources intended for use in other states, Noble said coal production generated about $211 million in revenue for Wyoming in 2017.

“The assessed value for all minerals in the state is (about) $10 billion,” he said. “And coal represents (about) 15 percent of all of the taxable value in the state.”

Labor force impact

While coal revenue could fill the state’s coffers for another decade, the Blackjewel layoffs might significantly hinder local economies in northeastern Wyoming.

“In May, unemployment (in Campbell County where the Blackjewel mines, Belle Ayr and Eagle Butte, are located) was down to 3.2 percent, which is pretty low,” said David Bullard, a Wyoming Department of Workforce Services senior economist. “We won’t have July’s numbers for a while yet, but just talking in round numbers, it could push unemployment (in the county) up to 6 percent.”

Wyoming’s average unemployment rate was 3.3 percent in May.

Campbell County’s labor force has trended downward in recent years with about 24,600 in May 2016 dropping to about 22,700 by May 2019, Bullard said.

“In general terms, if these 600 (Blackjewel) jobs disappear, we would expect that to have a negative affect across the local economy, and to a lesser extent, the entire state,” he said.

With about 4,000 jobs catalogued by Workforce Services, mining is one of the largest employment categories in the county, and Blackjewel’s employees accounted for about 11 percent of the sector, according to the department’s data. If the company is not able to secure more funding for its Wyoming operations, Bullard said the community could suffer.

“I expect a significant number of (the laid-off Blackjewel workers) would move away for other opportunities in other areas,” he explained. “That would impact the local economy by lowering demand for services and retail as well as tax revenue for governments and schools.”

More than three decades ago, U.S. Steel closed its iron mine in central Wyoming, but Case said the memory is still fresh.

“I’ve been through it in Lander, and when the mine shut down, we lost 550 good-paying jobs,” he recalled. “It is a killer — these are good jobs. You got $70,000 (a year) household incomes coming out of those mines. That money is in those communities. It’s scary. It’s truly scary.”

The future

As coal revenue wanes, legislators are reviewing options to keep the state afloat.

“It’s revenue that Wyoming has depended on for over 100 years,” Zwonitzer said. “With that gone — it’s a sizable chunk of the budget. There’s a lot of concern in the revenue committee.”

Increasing taxes on wind and solar energy is one possible avenue, but Zwonitzer said even the best estimates of potential revenue from renewable energy don’t come close to covering the gap left by coal.

“I think our two main options right now are a corporate income tax or a significant increase in property tax,” he added. “They may not be two good options, but they are the two palatable options right now.”

Case said some are looking to the oil and natural gas industries for answers.

“I’m just asking the question: what if oil were to go the same route?” Case posited. “We need to find a way to find long-term revenue for our state, our schools and our roads.”

As the era of coal-fired power plants nears its end, Zwonitzer said the revenue committee will continue to research ways of lessening the blow to Wyoming’s economy. But for now, the future is bleak.

“There’s no good news ahead,” Zwonitzer said. “It just keeps getting worse.”