By James Chilton, Cowboy State Daily

CHEYENNE — Once upon a time, coal helped to usher in a new technological age. So much concentrated energy in such a convenient package helped power the steam engines that drove the Industrial Revolution, transforming the way we live and work. Now, with coal’s future anything but certain, innovators are looking for new uses for the mineral that could fuel a new carbon-based high-tech manufacturing industry.

Coal’s fortunes have fallen in recent years – once the preferred fuel source for power plants, the mineral has been supplanted by cheaper, cleaner-burning natural gas in many places, while renewable energy sources like wind and solar have also been ramping up. And while coal is far from dead as a fuel source – China and India alone consumed about 4.56 billion tons of it in just 2017 – international pressure to ultimately phase out coal as an energy source remains strong, with at least 10 European Union nations now vowing to eliminate coal power by 2030 and similar draw downs and moratoria on new coal plants announced even in large coal-consuming nations including China and India.

Wyoming produces more coal than any other state in the U.S., and the mineral severance taxes paid to Wyoming for its coal comprise a large portion of the state’s annual revenues. But where once that amount rose steadily, from $85.3 million in Fiscal Year 1999 to $294.3 million in FY 2011, it has since been in decline, with the state’s Consensus Revenue Estimating Group (CREG) projecting coal severance taxes of $192.3 million for FY 2019, and continuing to drop through 2024.

The shift in coal’s economics have led innovators to look for new uses for the mineral, and Randy Atkins, CEO of Ramaco Carbon in Sheridan, is among those leading the push locally. Atkins said that while coal is best known today as fuel for power plants and as a reducing agent in the steelmaking process, it was once believed to have potential far beyond just those uses.

“There used to be a thing called the ‘coal tree’ in the early part of the 20th century. In Germany and even the U.S. they had these tree drawings, it was all the various things you could make from coal,” Atkins said. “We were making all sorts of chemical products, drugs, cosmetics, you name it; all from coal.”

That changed following the invention of catalytic cracking, the process by which crude oil is broken up into smaller molecules that are then made into refined products like gasoline, plastics, and a myriad of other uses. From then on, Atkins said, exploration of coal’s alternative uses effectively evaporated.

“I wouldn’t even say it was left by the wayside, it’s just all the technology advanced through the use of petroleum,” he said. “If you go back to the ’80s there were a couple attempts to make coal to fuels, and that involved making what looked like a refinery for processing coal. … But it’s really been the last three years that some of this stuff has started to come together in ways that began to make the argument that coal needs to be given a second look for uses beyond combustion.”

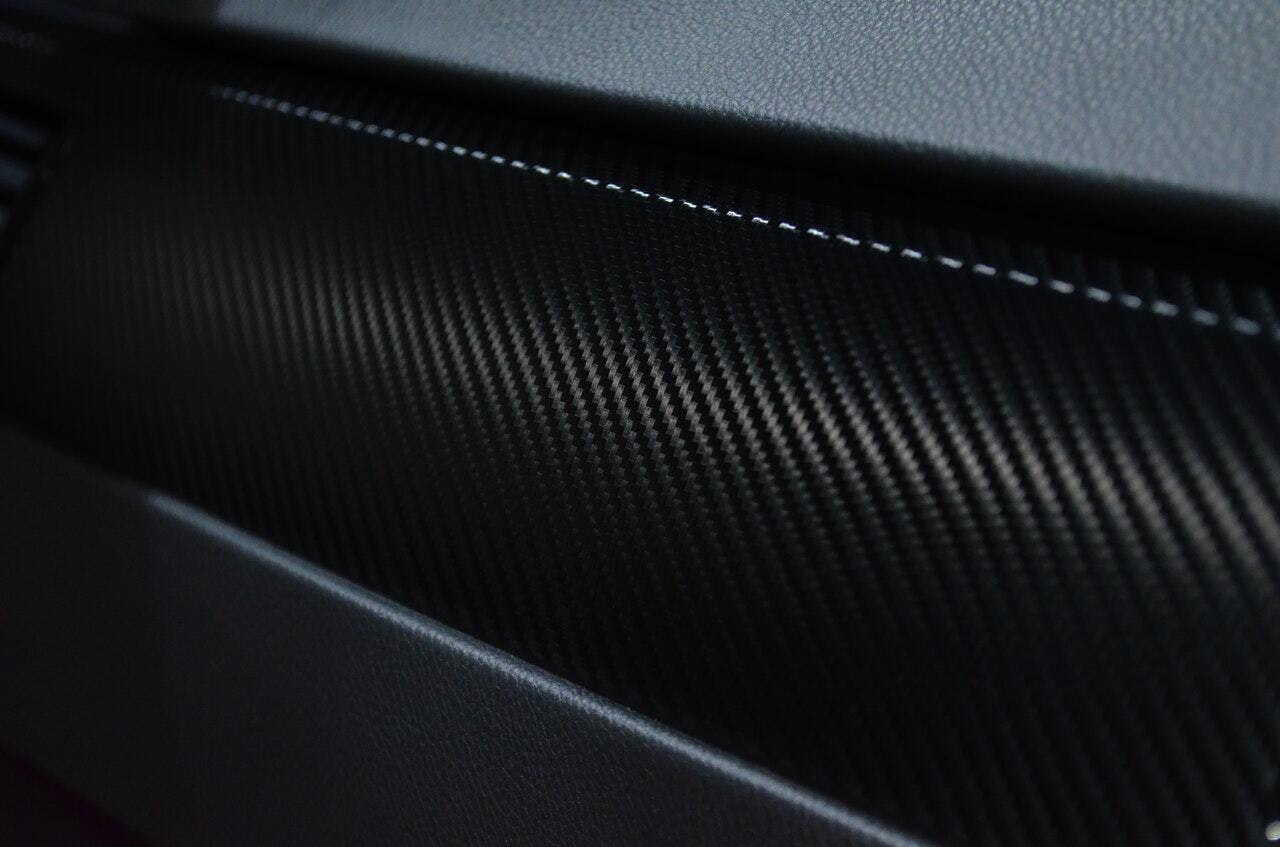

Since coal is primarily composed of carbon, Atkins and like-minded researchers have been looking at coal’s potential as a source for carbon fiber, a high-strength, low-weight material used primarily in aircraft and the aerospace field, but with the potential for many other uses.

“What we’re trying to do with carbon fiber is to make it dramatically less expensive than today’s use of carbon fiber from petroleum,” Atkins said. “Right now prices are $25 to $45 a pound for (carbon fiber) precursor made from petroleum. We think we can get that down to five bucks.”

In fact, Atkins, along with other members of the National Coal Council, contributed to a report published earlier this spring at the behest of the Department of Energy, “Coal in a New Carbon Age: Powering a Wave of Innovation in Advanced Products and Manufacturing.”

The report lists carbon fiber as just one of many potential coal products likely to see increasing demand in the 21st century. Other uses include advanced prosthetics, biosensors, electrodes, fertilizers and as a medium for 3D printers. And at a cost of $12 to $50 a ton versus nearly $500 a ton for petroleum, Atkins believe coal could find mass appeal again as further uses and innovations are discovered.

“As this becomes more widely known, I think we’ll see some fascinating breakthroughs in materials science,” he said. “Twenty or 30 years from now we may look back and say ‘My gosh, the 2020s were when we switched from widespread use of steel and aluminum to widespread use of carbon fiber from coal,’ that’d be huge.”

If and when those breakthroughs occur, Atkins hopes they’ll be under the roof of iCAM, or the Carbon Advanced Materials research park currently under construction in Sheridan. There, Ramaco Carbon plans to host researchers “from national laboratories, universities, private research groups and manufacturing organizations” in a collaborative effort to unlock the potential of coal’s carbon content.

Ultimately, Atkins’ plan is to develop an entire “Carbon Valley” akin to northern California’s Silicon Valley, with both research and manufacturing facilities fed by an adjacent coal mine.

That proposed coal mine, the Brook Mine, would be the first new coal mine in Wyoming in half a century, and one Atkins said would be relatively tiny compared to some of the extant mines in the state. But it has yet to materialize after Wyoming’s Environmental Quality Council rejected the mine’s permit application in September 2017 amid concerns over the potential environmental impacts. Ramaco’s appeal of that decision was heard in state district court in Cheyenne earlier this month, even as the company has submitted a revised permit application to the Department of Environmental Quality.

Even if the mine is ultimately approved, and in spite of his optimism about coal’s potential, Atkins says he doesn’t expect carbon fiber production will be what reverses the drop in severance taxes – at least not in the short-term. But in time, he believes coal’s high-tech uses could be what keeps mining a viable industry in the worst-hit parts of the state.

“As products develop over time … mines that can’t make it selling their coal at $12 to $15 a ton may be able to make it if they can sell at $25 to $40,” Atkins said. “I’m hopeful over a medium-term period this will provide an alternative demand for coal beyond its use as thermal coal.”

Travis Deti, executive director of the Wyoming Mining Association, believes Atkins’ proposals have promise, even if they don’t immediately offset the recent declines in production.

“What Ramaco’s doing with carbon fiber, graphene, graphite, 3D printing, that’s a great way to use our resource and make it viable in the future,” Deti said. “Is it going to replace the 300 million tons we’re mining right now? Probably not. But it’s an innovative use of the resource and it’s a great project.”

Deti said that while coal is still widely used internationally, especially in the Asia-Pacific region, it remains a hard sell domestically. While techniques for capturing and sequestering carbon dioxide from coal-fired power plants are still developing, he said, it’s important for stakeholders in the coal economy to find alternative uses of the mineral.

“We want to continue to use our coal for electricity generation, but it’s really a remarkable resource,” Deti said. “And looking at the direction of where we’re going right now in terms of electricity generation … we need to start looking at other avenues and ways of using the resource.”