By Ike Fredregill, Cowboy State Daily

Snubbing out a disease that causes cattle, elk and bison to abort their calves may not be feasible, but Wyoming is working to ensure it remains contained.

Brucella Abortus, a bacteria and one of the causative agents of brucellosis, was discovered in two northwestern Wyoming cattle herds in October. The latest in a line of several outbreaks of the disease since 2003, the affected herds were quarantined. But Wyoming State Veterinarian Dr. Jim Logan said the quarantine won’t prevent other herds in northwestern Wyoming from potentially contracting the disease from its primary vector — wildlife.

“In animals, (Brucellosis) is transmitted orally,” Logan explained. “If an (infected) aborted fetus or placenta or fluids get on the ground during the time the bacteria is active, cattle, bison and elk are pretty curious and will lick at stuff like that.”

Brucellosis is at its most dangerous February through June, when the affected species are calving, but he said the bacteria could be active for months if environmental conditions are right.

Humans who are exposed to direct contact with Brucella Abortus are also at risk, said Hank Edwards, supervisor for wildlife health at the Wyoming Game and Fish Laboratory.

“It goes to humans, but it doesn’t cause abortions,” Edwards explained. “It does cause undulant fever, which is not usually fatal, but that means it’s a fever that rises and falls, rises and falls. It is a nasty, nasty disease.”

Both Edwards and Logan said meat from infected animals is edible. “This is not a food safety issue as long as the food is properly prepared,” Logan said. “To my knowledge, brucellosis has never been transmitted in that way.”

It is most commonly transmitted to humans from unpasteurized milk, he added. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, about 100 people are infected in the U.S. with the disease annually.

Infected wildlife

Introduced to the Greater Yellowstone Area around the mid-1800s, Brucella Abortus spread unchecked through local fauna until the 1950s, Edwards said.

In 1954, congressional funding was allocated for a cooperative state-federal brucellosis eradication program, USDA documents state. At the time, Brucellosis was rampant across the country with about 124,000 affected cattle herds identified through testing across the U.S. in 1956. By 1992, only about 700 herds were affected and in recent years, affected herds nationwide are frequently in the single digits, the USDA reported.

All 50 states are now listed by the USDA as brucellosis-free, but Edwards said Wyoming is home to one of a few remaining Designated Surveillance Areas (DSA) for the disease.

The DSA in Wyoming consists of Park, Sublette and Teton counties in their entirety and parts of Fremont, Lincoln and Hot Springs counties.

Game and Fish Department personnel regularly test the elk and bison populations — the disease can infect other wildlife, but is primarily transmitted by elk, bison and cattle — in the DSA. Edwards said approximately 30 percent to 40 percent of elk and about 60 percent of bison in the area have been exposed to Brucella Abortus.

“This is an incredibly complex disease,” he said. “We now have that disease in our wildlife population and that spills back into our cattle population.”

In some cases, the disease spreads through wildlife herds at state-run feedgrounds, then the infected species move to feed lines on private property where it can spread to livestock.

“We’ve always figured that to control brucellosis, we could eliminate those feedgrounds,” Edwards said. “But, in another case, we found brucellosis in elk herd near Cody, which did not have access to feedgrounds. So, closing feedgrounds is not going to solve the issue.”

While vaccines exist for cattle and bison, one has not been successfully developed for elk. Even if one did exist, Edwards said administering it to the entire elk population of northwestern Wyoming would be extremely challenging.

“All a vaccine does is limit the severity of the disease,” Edwards said. “It does not stop it from spreading.”

Livestock interaction

After decades of aggressively targeting the brucellosis in the U.S., the federal and state campaigns were successful and the disease disappeared from Wyoming’s log book for nearly 20 years.

One livestock case was recorded in 1988, then Brucellosis in cattle disappeared until 2003, Logan said. Since, about 12 cases have been recorded, occurring in ones and twos every couple of years, he recalled.

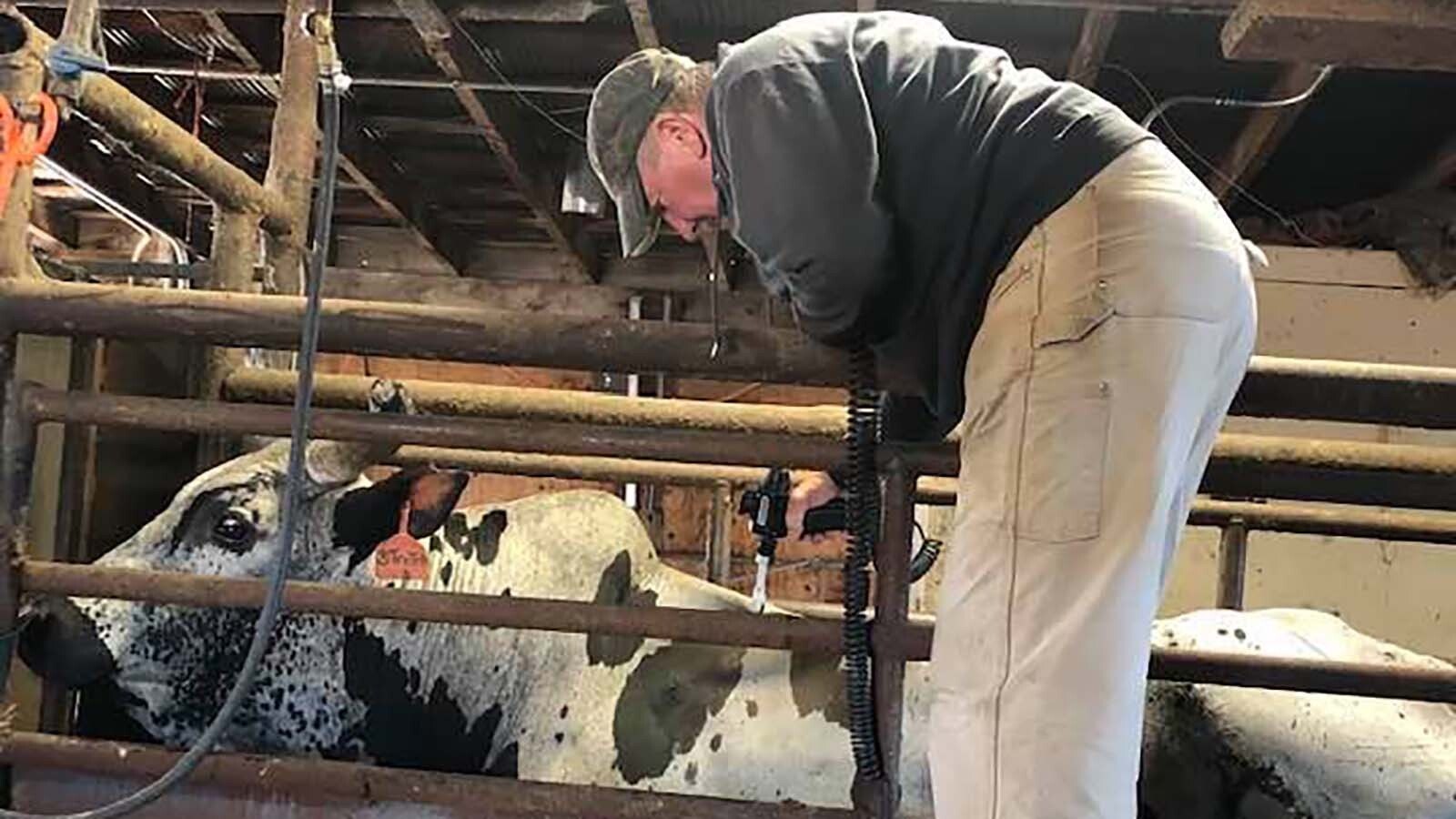

“If we get a positive result from a lab test … we immediately quarantine the herd from which the animal came,” Logan said. “That herd will be under quarantine until it has undergone three consecutive negative herd-wide tests.”

In the DSA, livestock producers are required to test their animals regularly. If an animal tests positive, producers are responsible for the quarantine. A positive test in the fall might not significantly affect their livelihood, because the herd would likely be on the home range during the winter months anyway, Logan said. But he explained a positive test in the summer could require the producer to keep the cows at home during prime range season, burning through valuable feed stores needed for the following winter.

There are several theories about the recent proliferation of Brucella Abortus, but Logan said he didn’t believe it could be attributed to a single reason.

“I think there are lots of factors that come to play in this,” he said. “Some of it is urbanization, some of it is the elk population increase and an increase in large predators. If you look back in history, a lot of this has a lot to do with the reintroduction of wolves (in Wyoming).”

Wolves were reintroduced to the Yellowstone National Park in 1995 and 1996, and a few years later, ranchers started detecting brucellosis in their livestock again.

“What I have been told from various producers is wolves are moving elk where elk had not been before,” Logan said. “As a result, there is more likelihood of interaction with elk and cattle.”

Some ranchers believe using a different vaccine — the original vaccine — would eliminate Wyoming’s livestock brucellosis problem altogether.

In 1997, state veterinarians nationwide banned the old vaccine, Strain 19, because it left a residual trace or “titer” in some animals, creating a false positive for brucellosis in later tests. The vaccine was replaced with RB51, which Logan said is just as effective.

“It creates immunity a little different than the old one,” he said. “But it does not create the titer.”

For now, constant testing and quarantines could be the best way to manage brucellosis in Wyoming, but Edwards said a solution might be needed soon.

“Brucellosis was introduced into the Greater Yellowstone Area around the Civil War, and for the most part, it stayed there — that’s something we can handle,” he explained. “But in the last six years, we’ve discovered it in the Big Horn Mountains. Here’s the scary part, because we have a disease we can’t really control, if it was to become established in a population like the Big Horn Mountains, there’s not a lot we can do to stop it outside of flying in a helicopter and culling all the elk.”