For decades, the Hitching Post Inn was known as Wyoming’s legislative dormitory, the digs where lawmakers and lobbyists hunkered by the hundreds each legislative session.

It was a place where rivalries softened, deals were made, and political foes became just folks brushing past each other in flannel pajamas.

“I had legislators tell me, ‘You can fight all day, but when you’re passing your foe in the hall when you’re in your pajamas, it’s hard to stay mad,'” said Sue Castaneda, author of the “Hitching Post Inn: Wyoming’s Second Capitol.”

They called it The Hitch, and Wyoming’s old guard say it was just as vital to passing legislation as anything that took place at the Capitol, in part because it meant lawmaking happened around the clock.

There were dinner parties seven nights a week. Small-hour conversations at the lounge bar, and an infectious ethos of good will and geniality, which began from the bottom up with a staff required to memorize the names of every legislator.

“That building on the hill might be the Capitol during the day, but the Hitching Post was the capital during the night,” said Dan Sullivan, former chair of the Senate Banking Committee.

“Everything we did to move things forward during the day as a legislator or a lobbyist, we were doing the same things at night, just at a different location,” he said.

The sense of camaraderie helped lubricate negotiations, and so might a dirty gin or two, readily acquired from a communal martini fountain.

Think of tiered fondue, but with booze.

It was “spewing from every spout. Guests could just walk over and refill their glasses out of the fountain. It was a crazy time,” said Sullivan. “But it was more of a schtick. No one’s drinking from a fire hose. We still had to wake up the next morning and function.”

Schtick or not, Wyoming’s old political establishment could hang one on, said Lynn Birleffi, former marketing director for the Hitching Post Inn.

“I will say there were probably people who had to be hauled back to their rooms occasionally,” Birleffi said. “But they could get away with that maybe one time. If they always drank like that, they wouldn’t make it through the session.”

Open Door Policy

It was sprawling hotel where doors stood wide open, conversations poured into hallways, and the midnight oil was always burning somewhere nearby.

“I mean, 90% of the legislators were there. So any night after a reception, you could just wander down the halls and somebody’d have their door open, and if the door was open, that meant come on in,” said Sullivan.

For longtime powerbrokers like Sullivan, who segued to a career in lobbying after leaving the Legislature, the place in hindsight was sickeningly familiar, specifically room 270.

“I actually figured it up one time, and I’d spent three and a half years of my life in that room. It’s just kind of sickening,” he said.

Lawmakers jockeyed for rooms with southern sun and drive-up parking, and the pecking order shifted each election cycle, said Del Peterson, former general manager.

“It got to be really contentious toward the end, because they all knew who had which rooms," said Peterson. "After the session, I’d get a call from some legislator who’d say, ‘You know, so‑and‑so got beat in his election. Can I have his room?’

“It became a real game of chess fitting everybody in just right.”

They also knew which rooms and areas to avoid. If they needed to focus on quiet work, they’d have been smart to steer clear of room 270.

Driving Range In Hotel Room

Sullivan described room 270 as his home away from home. He might have also called it his driving range away from home.

He removed one of the queen beds and threw down a turf mat. Then he whacked golf balls at the blackout curtains.

“If I wanted to clear my head, I could just stand up and hit golf balls for 20 minutes,” he said.

Meanwhile, in the room next door, then state Sen. Mike Enzi was losing his head.

“Mike … had a hard time concentrating because I was hitting golf balls next door,” Sullivan said.

The Hitch took a hit here, too — on curtains, suddenly riddled like the OK Corral.

“I didn’t realize it, but over time I wore holes into those curtains. One day I closed them and the sun was coming through and shining little round blobs of light all over my room,” Sullivan said, going on to declassify a key detail.

“I didn’t tell anybody about the curtains, and I don’t know if they ever replaced them," he added.

That moment might have been Enzi’s reprieve. Instead, Sullivan brought in a real golf net.

‘Spiro Agnew Made Me Move’

It was not just local politicians who vied for rooms here.

Spiro Agnew, then U.S. vice president to Richard Nixon, stayed at the Hitch.

His special services agents scanned the wing and deeply inspected his room ahead of the visit.

But someone still managed to breach security.

“I got a call at 2 in the morning from Agnew’s lead security guy and he said, ‘Del, we’ve had a security breach. It’s a problem. Somebody went into the secure area and they’re sleeping there,'” said Peterson.

Flanked by personnel, Peterson knocked on the door an hour later.

Alan K. Simpson, then serving in the Wyoming House, answered indecently.

“Alan opened the door in his underwear and said, 'Del, What’s the problem?' I said, 'Alan, I’m sorry' but I gotta move you right now," Peterson said.

Simpson and Peterson crossed paths many times afterward, and their conversations were always the same.

“Every conversation I had with Alan K. Simpson after that started off this way: 'Del, you remember when that asshole Spiro Agnew made me move in the middle of the night?’” he said.

Presidents

The place welcomed other big timers, celebrities and U.S. presidents among them.

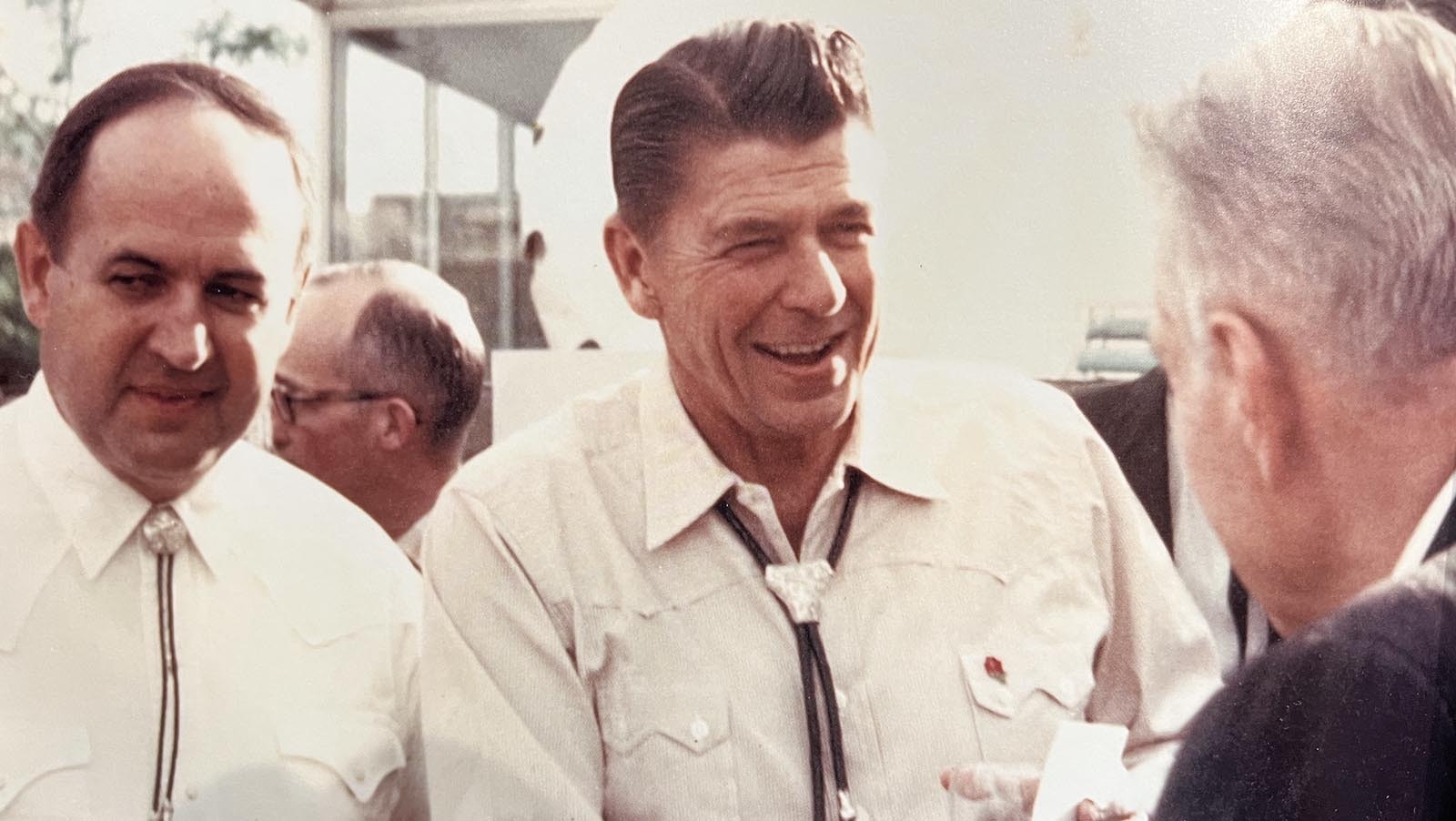

Ronald Reagan worked the ropes during a rally there dressed in a Western shirt, stone bolo and silver belt buckle. George Herbert W. Bush wore a dark, sober suit for his Hitching Post meet-and-greet.

Robert F. Kennedy left a big impression on Cheyennites during his stop there in 1968, one month before his assassination.

Banquet Waitress Doris Woodcock recalled the atmosphere following his death.

“The Hitch was like a morgue the day he was shot. A chill goes down your spine when it is someone you’ve actually met,” she wrote in the “The Hitching Post Inn.”

These visits underscore how far the place came from simple beginnings.

Simple Beginnings, Family Feud

It began in 1927 with a Russian Jewish immigrant named Pete Smith, who started the Lincoln Campground at the site, and later built it into the Lincoln auto court.

Pete passed it to his son, Harry Smith, who modernized, expanded, and rebranded as the Hitching Post Inn.

In the 1960s, he made a full-court press to get the legislators — and the lobbyist dollars that followed them — to stay during the session by offering rock-bottom room rates as low as $5 a night.

They knew a deal when they saw one.

“They all came, only the Cheyenne delegation was not staying at the hotel,” said Peterson. “We didn’t have enough room … some of the legislators actually doubled up. But we continued to build rooms every year.”

'Tale Of Two Men'

The Hitching Post went through a stark transition when Harry Smith decided to step away. He entertained a variety of offers before deciding to sell to his son, Paul Smith.

But the baton didn’t pass gracefully.

The men were exceedingly different in business, according to Peterson, who went to high school with Paul and began working for his father as a bellhop at the age of 15.

Harry Smith, the immigrant’s son who turned a windswept auto court into Wyoming’s most famous political hub, ran the hotel with an old‑school and intensely personal style.

He was there from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. seven days a week.

“He knew absolutely everything that was going on there,” said Peterson. “He was the best hotel operator you could imagine. I was successful later in my life, in my own businesses, simply from what I learned from him. He was brilliant."

His son was of a different mind.

Paul Smith went to Michigan State University to study in the hospitality business program, and he returned with new ideas for The Hitch.

He excelled at creating experiences and atmosphere, and he had a touch for detail.

“Paul (Smith) would have flowers on the big table in the lobby and make sure it was all decorated, but he might not see that the roof needed to be fixed,” said former legislator Grant Larson in “The Hitching Post Inn.”

Safe to assume the martini fountain was Paul’s idea.

He also had the mindset to delegate.

“Harry carried everything around in his brain all the time, but Paul tried to delegate and he tried to set up systems that could really work,” said Peterson. “It was really a tale of two men, just a completely opposite way of operating.

"And it was part of the problem, because Harry didn’t accept that.”

Caught Between Father And Son

Harry agreed to retire when Paul bought the establishment. Instead, he set up a new office at the property and tacitly maintained control.

Peterson was caught between father and son.

“Harry stayed on, and he was there every day just like he was running it," he said. "I’d hear him whistle me into his office, and he’d say, ‘Don’t tell Paul I told you this, but make sure this gets done.’

"II’d worked for him for 20 some years, and he was like a father to me. I wasn’t gonna tell him no.”

It always came back around.

“Paul would say, 'You’ve been talking to dad again, haven’t you?' It made him so mad he left,” Peterson said, explaining that Paul stepped away from running the business for three years.

Peterson reasoned that if he himself left, father and son would reconcile, because Harry would become desperate enough to finally agree to Paul’s terms.

“If it hadn’t been for that dynamic, I’d have probably been with Paul to the bitter end because I loved it so much and we worked perfectly," Peterson said. "He was so good at taking care of people, and I was good at administrating."

It worked. Peterson left, Harry capitulated, and Paul came back.

By then, however, the institution was staggering with debt, too cash short to stay competitive.

Paul Smith died of pancreatic cancer in 2006. Under new owners, it continued to decline, and in February 2009, the hotel owners filed for bankruptcy with $3.6 million in liabilities.

That news was quickly followed by an announcement from Cheyenne Light, Fuel and Power.

“Someone called … and said the legislators had one hour to come and move their stuff,” wrote then-Senate President John Hines in the “The Hitching Post Inn.”

Hines made the announcement in Senate chambers and adjourned so legislators could move out.

Management negotiated to keep the power on through the session. Some left anyway, but not Hines.

“I knew the place so well I could have moved out in the dark,” he wrote.

‘Till The Absolute Bitter End’

The next year, the property was finished off in an arson fire as part of a scheme to collect on a $13.6 million insurance policy. They succeeded in burning down the hotel, but never collected the insurance, and one man was sentenced to six years in prison.

“That day I got a call at 6 in the morning from a friend of mine who said, ‘Del, you got to go to the Hitching Post. It’s on fire,’” said Peterson, explaining the emotional pain he felt as he stood in the flurry of embers.

“I stayed down there the whole day with 15 of my old co-workers," he said. "We sat there and watched that place burn down. It was so disheartening. Till the absolute bitter end, my heart was still with the Hitching Post.”

What Else Went Away With The Hitch?

In the years since The Hitch lost its corner on the legislative market, no other hotels have been able to replicate that same sense of loyalty among Wyoming’s governing set.

Lawmakers have scattered across Cheyenne, and they may never congregate in the same way again.

“I think the way we all approached things during the Hitching Post days was much better. But people serving now will tell you: 'That was yesterday, this is today, and it doesn’t make sense to do it like that anymore,'” said Sullivan. “You couldn’t really say it’s better or worse. It’s just the evolution of things.”

Yet there’s a sense among some that more than a hotel went away with The Hitch, and that its legacy offers lessons in need of attention.

Making connections unconstrained by the protocols of Wyoming's Capitol Hill, sharing meals and talking eye to eye, helped lawmakers see one another as people rather than opponents, said Liz Brimmer, chief of staff for former U.S. Sen. Craig Thomas.

“It’s a real difference when you have an earnest conversation over a meal or in a close setting. Sometimes you hear things differently. The real dynamic of the place is that people experience their own opinions being respected,” said Brimmer, whose first job at the age of 13 was working as a gardener for Paul Smith.

“That meant people who may have disagreed could still have a friendship," she said.

Sue Castanada, author of "The Hitching Post Inn,” expressed that sentiment this way:

“It was a place where people could just be real people, not be Democrat or Republican, or anything else,” she said. “Politics has always been contentious, but it feels way more contentious now than it was when the Hitching Post was there.”

Zakary Sonntag can be reached at zakary@cowboystatedaily.com.