When a Minnesota backpacker disappeared in the Bighorn Mountains last summer, dozens of local search and rescuers raced against time, scouring the rugged mountainous terrain to find him.

Grant Gardner, a 38-year-old experienced hiker from Lake View, Minnesota, disappeared on July 29 after summiting the 13,166-foot Cloud Peak Mountain in north-central Wyoming.

Search and rescue ( SAR) personnel led by the Big Horn Sheriff’s Office along with neighboring SAR groups and the Wyoming Army National Guard scoured the area for 20 days by foot, horseback and multiple helicopters and airplanes.

Those search efforts were not successful, but Gardner’s remains were found a month later by a professional hiking team from North Carolina who found the deceased man between two rocks on the mountainside with his body obscured from view in an area that had been searched by aircraft.

Local SAR professionals were dispatched to recover his remains.

In light of the tragedy, what doesn’t get discussed is the exorbitant cost of the rescue efforts conducted mostly by volunteers who donate their time – and in this case – aircraft with local pilots stepping up to help.

Big Horn County Sheriff Ken Blackburn credited the generosity of these volunteers who made the 20-day search affordable at around $65,000.

Without the volunteer support, Blackburn estimated it would have cost about $1.7 million when factoring in the 1,785 of documented manpower hours at around $20 per hour and the 220 flights with each running about $5,000 an hour.

“There are so many good people in the Big Horns and so many volunteers that stepped up to help with that search,” Blackburn said. “That’s the price of volunteerism right there.”

How It Works

The number of out-of-state visitors topped an estimated 8.8 million last year on top of a booming outdoor recreation industry attracting both locals and visitors alike. Wyoming outdoor spaces are getting increasingly busier.

Depending on the remoteness or breadth of the rescue, costs can escalate into the thousands of dollars within the first couple days.

And when a person gets lost or hurt in these outdoor spaces, the cost of finding or saving them diverts back to that county’s SAR group, which by state statute falls under that county’s sheriff’s office. SAR services are free to the person or persons being helped.

Most – if not all – SAR members are unpaid volunteers who conduct searches on their own time, sometimes using their vacation time to attend trainings. These volunteers stand ready to dispatch at any time and day of the year.

Often neighboring counties step in to help each other and SAR groups can also request assistance from the National Guard, Civil Air Patrol and other private entities with specialized equipment such as helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft or underwater search tools.

SAR teams are funded by their county commission who typically cover the costs of vehicles, gear, buildings and sometimes help with SAR retirement programs.

Private citizens can also donate to SAR groups as in the case of Gardner’s family.

His sister, Heather Widness, who was on the ground helping with search efforts, is currently doing a GoFundMe to support Big Horn Search and Rescue in conjunction with her running the Atlanta Marathon on March 1.

Widness writes on the GoFundMe that she and her brother were supposed to run together, so now she’s running in his memory with the goal of giving back to the people who helped find him.

Other county SAR teams such as Teton and Carbon counties have turned their groups into 501(c)(3) nonprofits in order to garner grants and donations.

Additional SAR funding also comes from those who voluntarily choose to donate $2 or more when purchasing a fishing, hunting, boating or snowmobile licenses as well a small percentage from ATV and snowmobile stickers.

These funds are overseen and administrated by the Wyoming Office of Homeland Security, which reimburses SAR teams for training, fuel or any broken or lost items or damage to vehicles that occurs during a search and rescue operation.

Groups can also apply for reimbursement for expenses well beyond their budget such as the cost of renting aircraft.

Reimbursement of the funds is determined by the 11-member Wyoming Search and Rescue Council appointed by the governor that meets twice a year to review the requests.

Currently, as of Jan. 31, the state fund sits at just under $1.9 million, according to Ashley Paulsrud, grants and finance chief for the department.

In 2025, there were 422 state-wide missions for which the council reimbursed $220,000 for mission costs and training that may also include missions from 2023 and 2024.

The bulk of those expenses were for aircraft used on missions, which Paulsrud said is very costly expense on top of training expenses that continue to rise as SAR volunteers attempt to keep up with extreme athletes including swift water, advanced rope and high-angle rescues to name a few.

Those in the field worry that this funding is not enough and can be easily wiped out with one emergency such as the search for missing hiker, Austin King, who vanished after summiting Eagle Peak in Yellowstone National Park last fall.

That search falls on federal agencies who also pick up the tab, Blackburn noted, estimating that the cost for those efforts likely exceeds $1 million at this point as an example of how easily the SAR fund could be wiped out.

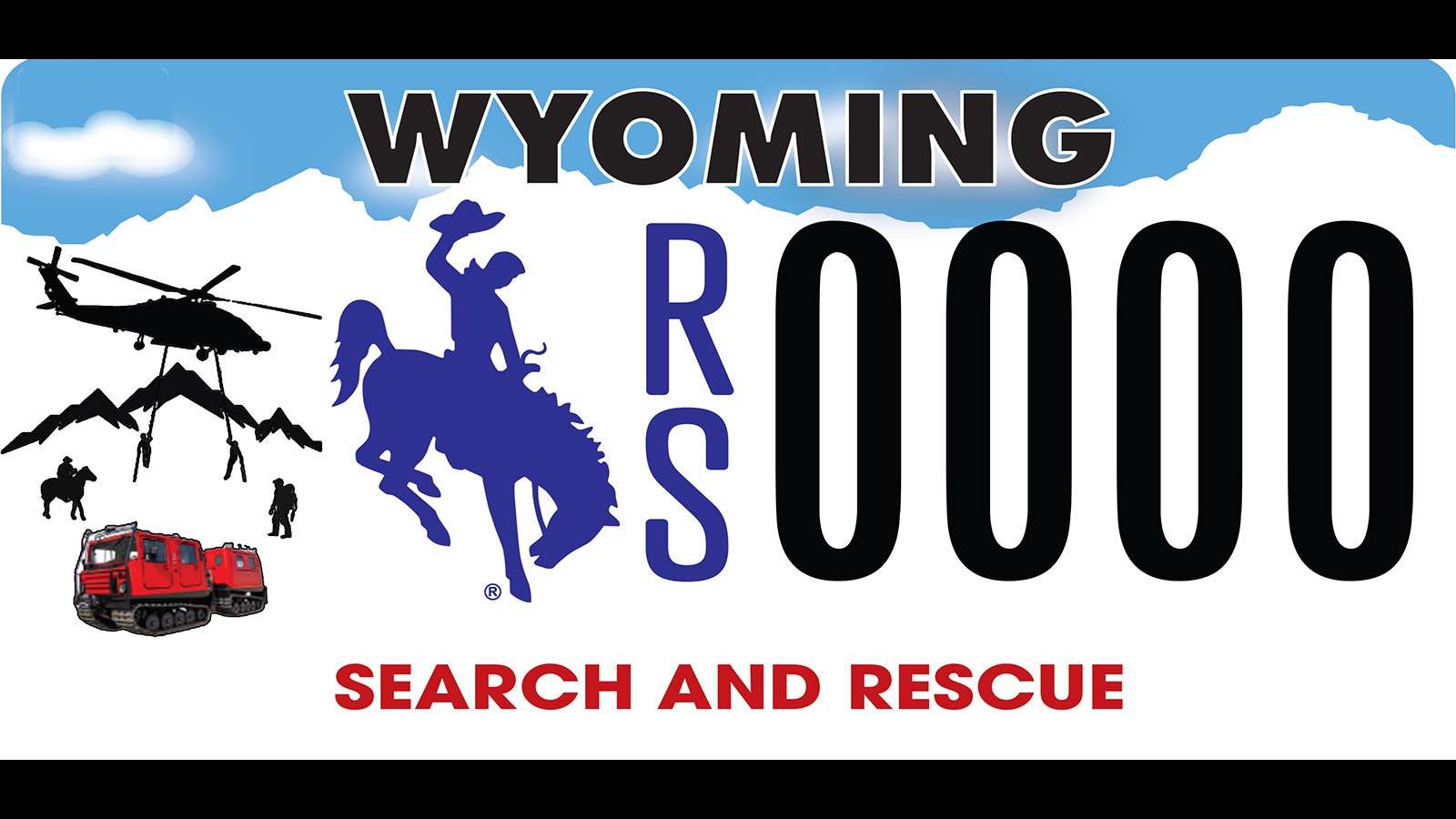

New License Plate

For this reason, SAR professionals like Converse County Sheriff Clint Becker, who is also a member of the Wyoming Search and Rescue Council, are getting creative for ways to pad the state-wide fund.

As of January, thanks to legislation that passed last year, residents can now help fuel these efforts by purchasing a specialty license plate for $180. Of this cost, $150 goes directly to the fund with a $30 fee going to the Wyoming Department of Transportation for the license plate. Residents can renew the plates annually for $50.

Residents do not need to wait until their registration expires to buy a specialty SAR plate and can do that at any time at their local treasurer’s office with the license plate expiring at the same time as their original plate.

There’s also a limited number of low-number plates one through 10 as well as 100 and 307 that are currently being auctioned off on the Wyoming Department of Transportation Surplusi website. The plates are being auctioned in three lots through the month of February.

Plate numbers one through 5 will be auctioned from Feb. 9 to 23. Plates six through 10 will be auctioned off between Feb. 10 and Feb. 24, with the final lot of plates 100 and 307 being auctioned between Feb. 11-25..

Anyone interested in joining the auction can register here.

Becker urges residents to help support SAR efforts because that person might never know when it’s their turn to be rescued.

It can happen to anyone, Becker noted, whether they take a wrong turn or get misled by their GPS and get stuck in the snow on an isolated road or have an accident while hunting, which recently happened to a hunter who had fallen about 20 feet off a rock while hunting outside Glenrock.

The man was unconscious from the fall and would have likely died of hypothermia had the SAR volunteers not found him in time with the help of locals who knew the area and knew where to take them.

“They saved the guy’s life,” Becker said. “It could have easily ended with a tragedy if they didn’t have the skills and training to get there in time.”

Becker also said a common mistake that lands people in trouble in his county is people misreading the weather and underestimating storm forecasts like a group of people in multiple vehicles who got stranded in a snowstorm on Laramie Peak in Converse County and had to be driven out in a snowcat.

More Extreme Sports, More Extreme Rescues

As Sheriff Blackburn noted, recreators are getting more advanced and daring.

“The higher up on a cliff the people go to recreate and run into a problem, the higher up the cliff the search and rescue people have to go to get them,” Blackburn said.

This includes not only honing the SAR volunteers’ outdoor skills but also includes buying more advanced types of technical equipment and gear to be able to access them. Ice climbing in his county is becoming increasingly popular, which is also rife with injuries given the risky nature of the activity.

Last year, his county was the second busiest with 55 rescue missions that totaled 3,675 man hours and a cost around $96,000 due to the Gardner search with some of that reimbursed by the council.

Volunteers put in an additional 2,156 hours of training. That alone would have otherwise cost the county more than $43,000, factoring in $20 per hour, had the SAR professionals not donated their time. Currently, their SAR budget for this year sits at $50,000, though they are expecting a 5% cut.

Increasingly, it’s getting harder for SAR teams to keep up with demand as this year is already starting off with multiple rescues across the state.

Teton County Slammed

As of Feb. 13, there have been 27 search and rescue missions across six counties in Wyoming, according to the Wyoming Department of Homeland Security website. Of those, the overwhelming majority – 17 – occurred in Teton County. Both Lincoln and Park counties followed at three incidents apiece.

Next was Carbon County with two snowmobiling rescues followed by Albany and Sublette counties that each had one incident involving motor vehicles.

January is already proving to be a busy month for Teton County. This month, Teton’s SAR team has conducted one rescue for hunters, six cross-country or downhill skiers, and 10 incidents involving snowmobile accidents, including at least two fatalities.

The majority of those rescues involved out-of-state visitors.

Historically, between 2009 to present, Wyoming SAR teams have conducted 4,990 search and rescues with an average of 9.4 hours per mission.

Much like this year, the majority occurred in Teton County at 1,205 missions, followed by Lincoln County at 583 and Fremont at 503. During this period, rescue missions were conducted in all Wyoming counties with the least in Goshen at two and Platte at four.

Jen Kocher can be reached at jen@cowboystatedaily.com.