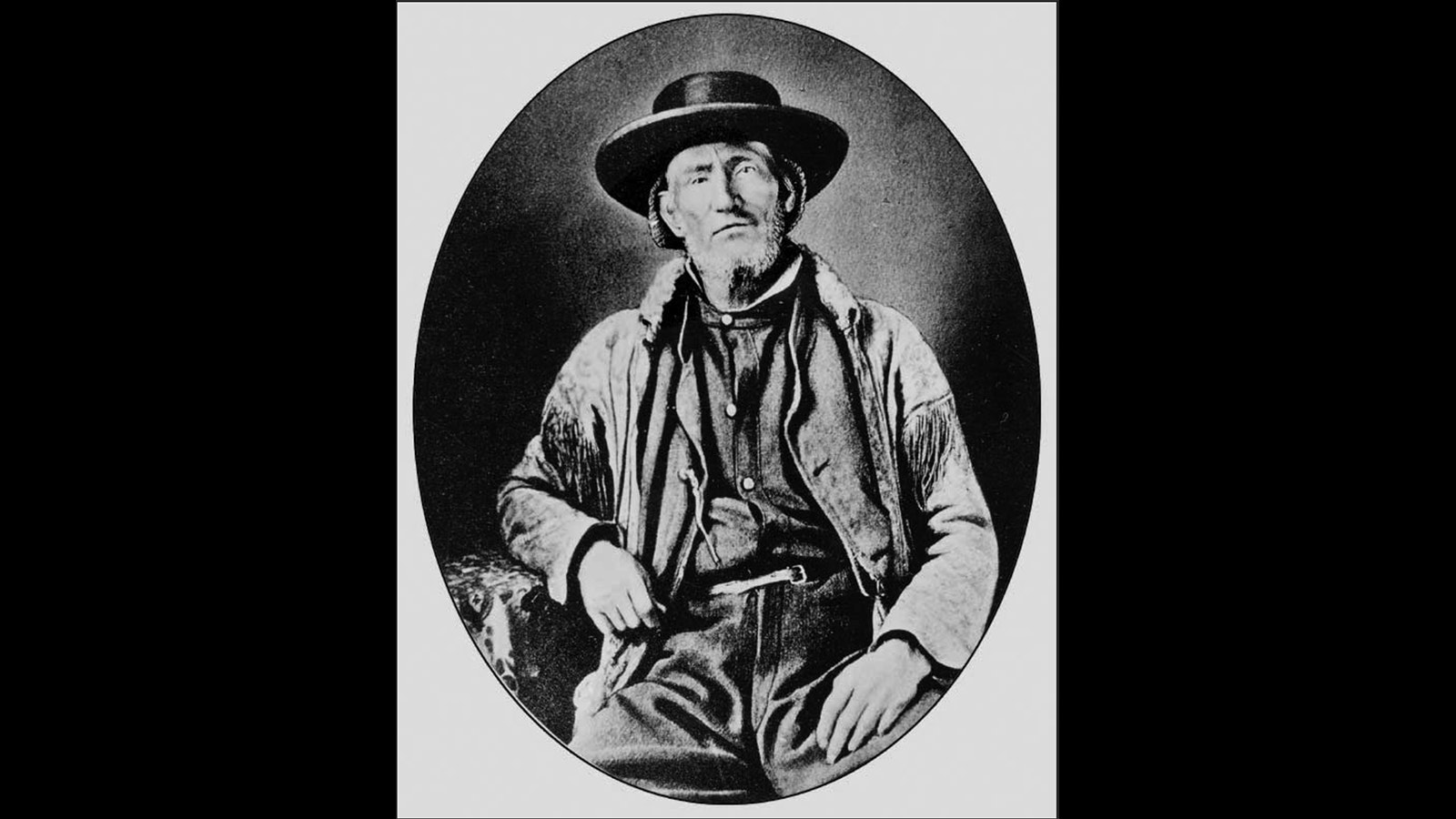

In the 1850s, members of Congress thought that the stories about Yellowstone were too fantastic to be true.

They believed that they were just the tall tales of trappers Jim Bridger and Joe Meek. These stories, known as “Bridger’s Lies,” flooded back East and spoke of glass mountains, boiling mud and a petrified forest.

The Centennial Post of Wyoming on 1909 wrote that Bridger had sought with much enthusiasm and sincerity to make the world acquainted with what he had seen, but he was not believed.

“His tales of the park region were scouted as fiction, and the incredulous attitude of the world made him resentful,” the Post reported. “Whereupon, to avenge himself, he made it his custom to tell fanciful tales about his experiences, most of which were of the impossible kind.”

According to Gen. Grenville Dodge who knew Bridger personally, a favorite story of the explorer was about a freshwater lake that was next to a boiling lake. Bridger said that he could catch a trout and slowly reel it in so that it would be fully cooked by the time he landed the fish.

Politicians in Congress openly scoffed at these stories and refused to believe that any of it was true. Captain Eugene Ware, who spent many hours listening to “Old Man Gabe” Bridger, said that admittedly the trapper would regale his audiences with ludicrous stories mingled with truth.

Bridger’s Tales

“One evening he told me that Court House Rock had grown up from a stone which he threw at a jackrabbit,” Ware said. “(Bridger claimed) rocks grew the same as trees and animals grow, only they grew larger and for a longer time.”

However, Ware said that Bridger was not an egotistic liar nor boastful.

To prove this point, Ware recorded a story Bridger had shared of Yellowstone that rang true. According to Bridger, he had watched two Indian braves cross a valley when suddenly they disappeared.

“The crust of the earth gave way under them, and they and their ponies went down out of sight and up came a great powerful lot of flame and smoke,” Bridger said. “I bet hell was not very far from that place.”

Ware said that it wasn’t until later that he realized that the Indians must have dropped through the ground in some part of the hot-spring or geyser country of Yellowstone.

Bridger had described to his disbelieving audience about water so hot that meat could be cooked in them and an acid spring that he had discovered.

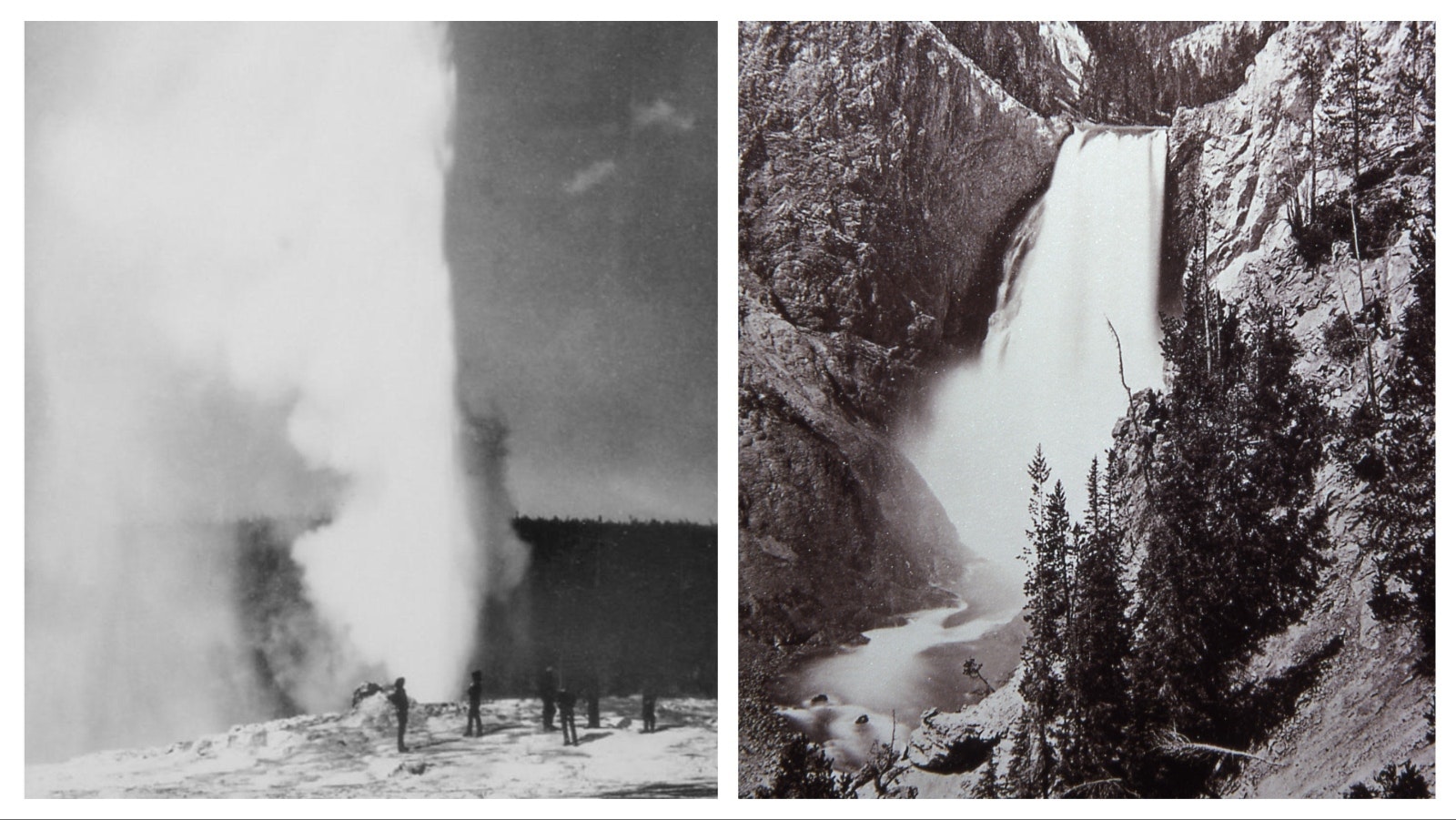

“Geysers spout up seventy feet high, with a terrific, hissing noise, at regular intervals,” Bridger said. “Waterfalls are sparkling, leaping and thundering down the precipices and collect in the pools below.”

No matter how often Bridger insisted these stories were true, his amused audience rarely believed him.

“For a long time the accounts of the wonders of the Yellowstone were received incredulously as trappers’ tales,” Dodge said.

Seeking Proof

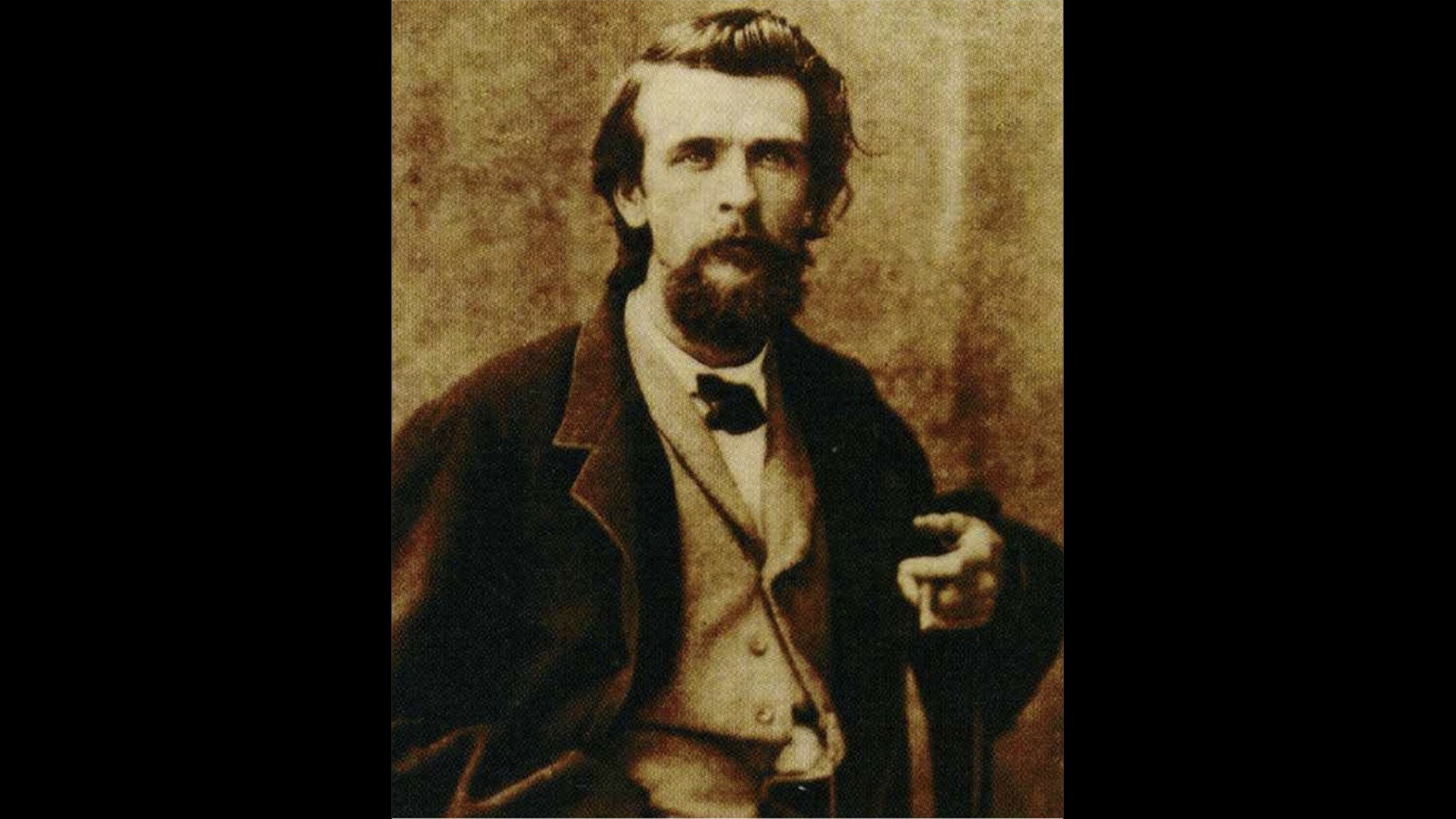

Geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden had been exploring and surveying the territories of Idaho and Wyoming in the 1860s for the U.S. Government and railroads.

He had never been to Yellowstone himself but was present at Nathaniel Langford’s 1871 lecture about the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition to Yellowstone of the previous year.

Intrigued by the fantastical stories and the added hope for building a railroad for tourism to this wonderous place, Hayden made plans to go himself. He petitioned the skeptical Congress for funding his fifth survey trip into the remote wilds.

This trip would soon play a prominent role in convincing the U.S. Congress that the myths of Yellowstone were real and to pass the legislation creating the park.

Included in the party was William Henry Jackson, Hayden’s photographer from his 1870 survey and Thomas Moran, a guest artist arranged by Jay Cooke, who didn’t even know how to ride a horse or shoot a gun.

The photographs and accurate sketches and paintings would finally prove to a disbelieving nation that Yellowstone was as fantastic as Bridger and the other trappers had said.

Proved True

“We found everything in the Geyser region even more wonderful than it has been represented,” Hayden said in a letter to the Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Dr. Spencer Baird.

These wonders were recorded in detail by Jackson and Moran who worked closely together to document the Yellowstone region.

Hayden’s surveys were annual multidisciplinary expeditions meant to chart the largely unexplored west, including the plants, animals and geology of the area. As the official photographer for the survey, Jackson was able to capture the first photographs of legendary landmarks of the West.

According to author Bradly Boner in “Yellowstone National Park: Through the Lens of Time,” Jackson used two cameras during the 1871 expedition. Jackson had an 8-by-10 camera, which yielded a single glass negative of that size, and a 6½-by-8½ stereoscopic view camera, which produced a pair of images side-by-side on a single plate, one slightly offset from the other.

While Jackson proved that the geological features were real, it was Moran who provided the color and emotion that truly sold Yellowstone to the world according to the historians at Yellowstone National Park.

The two men worked side-by-side and shared the same vantage points with Moran capturing the rainbow of colors created by the thermal basins.

The stunning photographs Jackson captured with these cumbersome cameras and the colorful landscapes painted by Moran played an important role in convincing Congress in 1872 to establish Yellowstone National Park, the first national park of the U.S.

Vindicated

After the trip, Hayden wrote to a member of the party that had to leave the expedition prematurely that Jackson had documented the trip with ‘abundant pictures’ and that Moran was enthusiastically painting the pictures of Yellowstone.

“We made a most admirable survey of the Yellow Stone Basin, the Lake, all the Hot Springs,” Hayden wrote. “I am sorry that you were not able to see the wonderful things in the Yellow Stone (sic) but when reports come before the world, you will get a pretty clear conception of them.”

As the pictures and paintings became known, Congress acted quickly and Yellowstone became America’s first national park.

“Quaint, honest old Bridger lived to hear his Yellowstone yarns vindicated, to see a railroad using his particular pass and trail, and to realize that his mountain days had not been wasted,” Dodge, the general, said of his friend.

Bridger’s “lies” about Yellowstone had been proved to be true after all. Bridger lived another decade, secure in the knowledge that he had finally been believed.

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.