The year 1918 was not a particularly safe one in the booming Wyoming oil patch.

Especially if you were hired by the Independent Torpedo Company and charged with delivering nitroglycerin to oil wells to blast them loose.

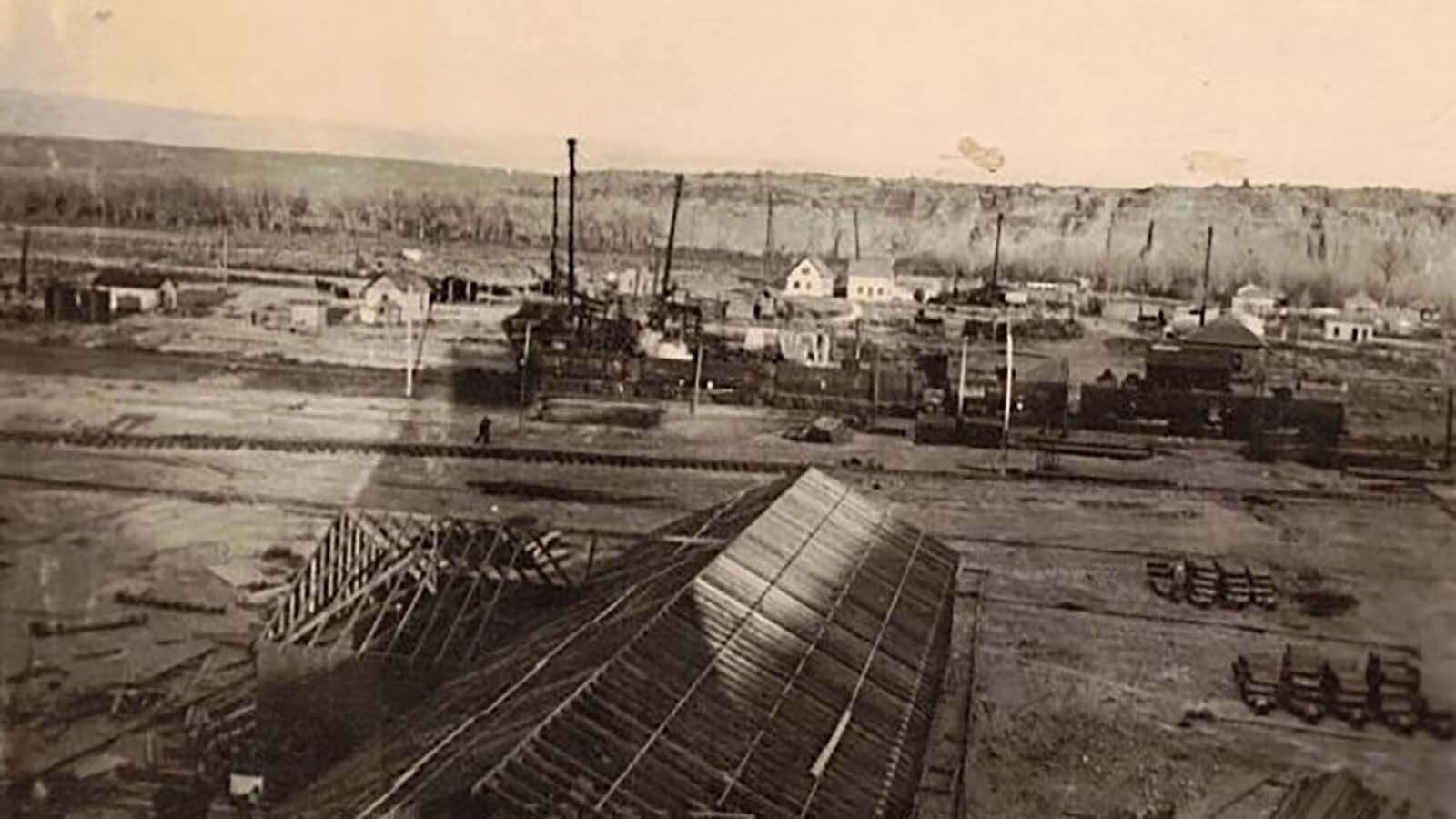

The company, formed in 1905 in Findlay, Ohio, arrived in Wyoming early in 1918.

The Casper Daily Tribune reported on March 18 that new companies were “chartering” in the state nearly every day.

The Independent Torpedo Company arrived that year worth $500,000 in stock value or $11.8 million in today’s numbers when calculating inflation.

In the first half of the year, the company’s commitment to manpower and materials would be tested repeatedly.

But the legacy of the firm’s human losses would help lead to a change in Wyoming law.

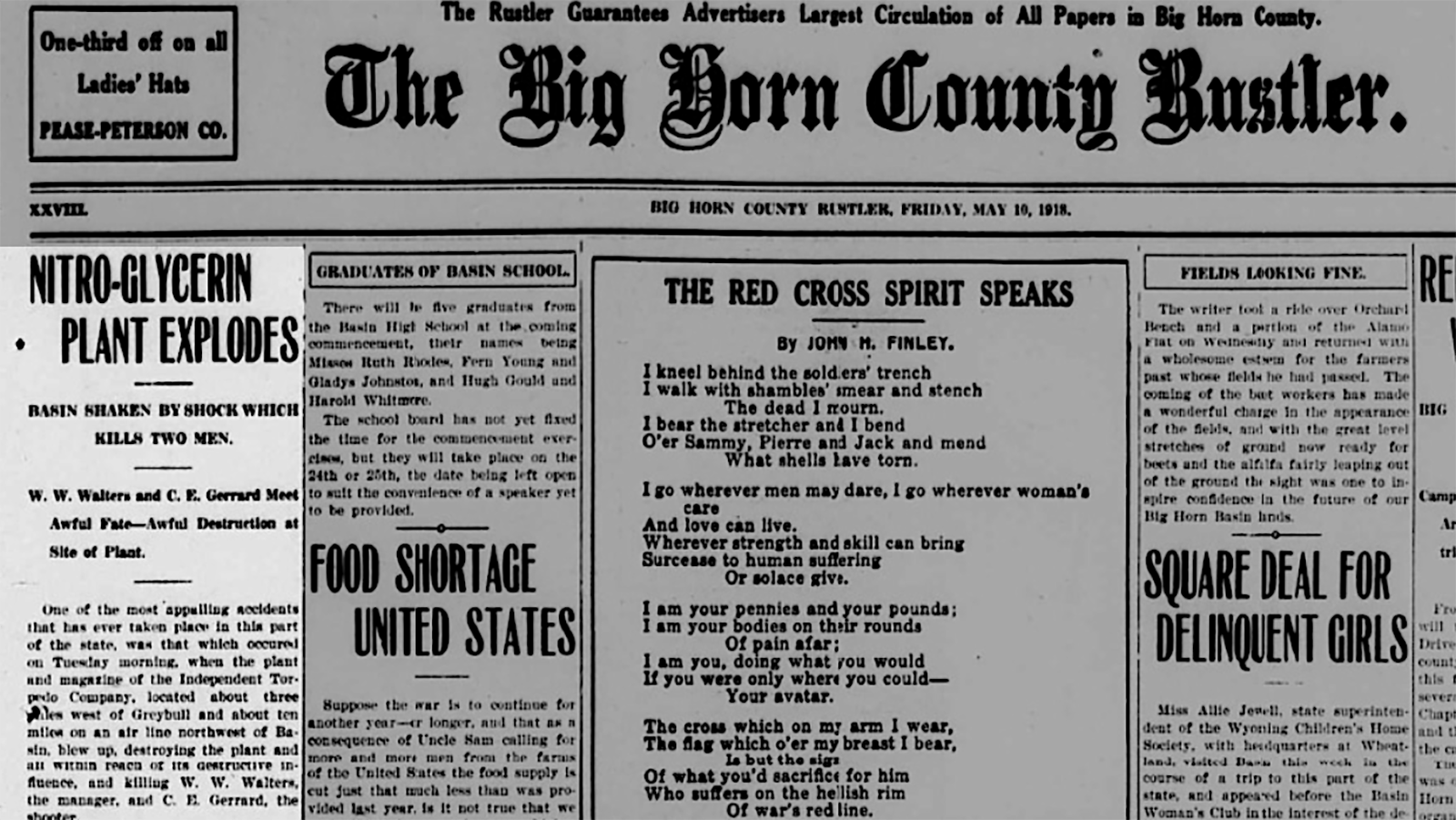

“Nitroglycerine Plant Explodes,” the Big Horn County Rustler reported on May 10, 1918. “Basin Shaken by Shock Which Kills Two Men.”

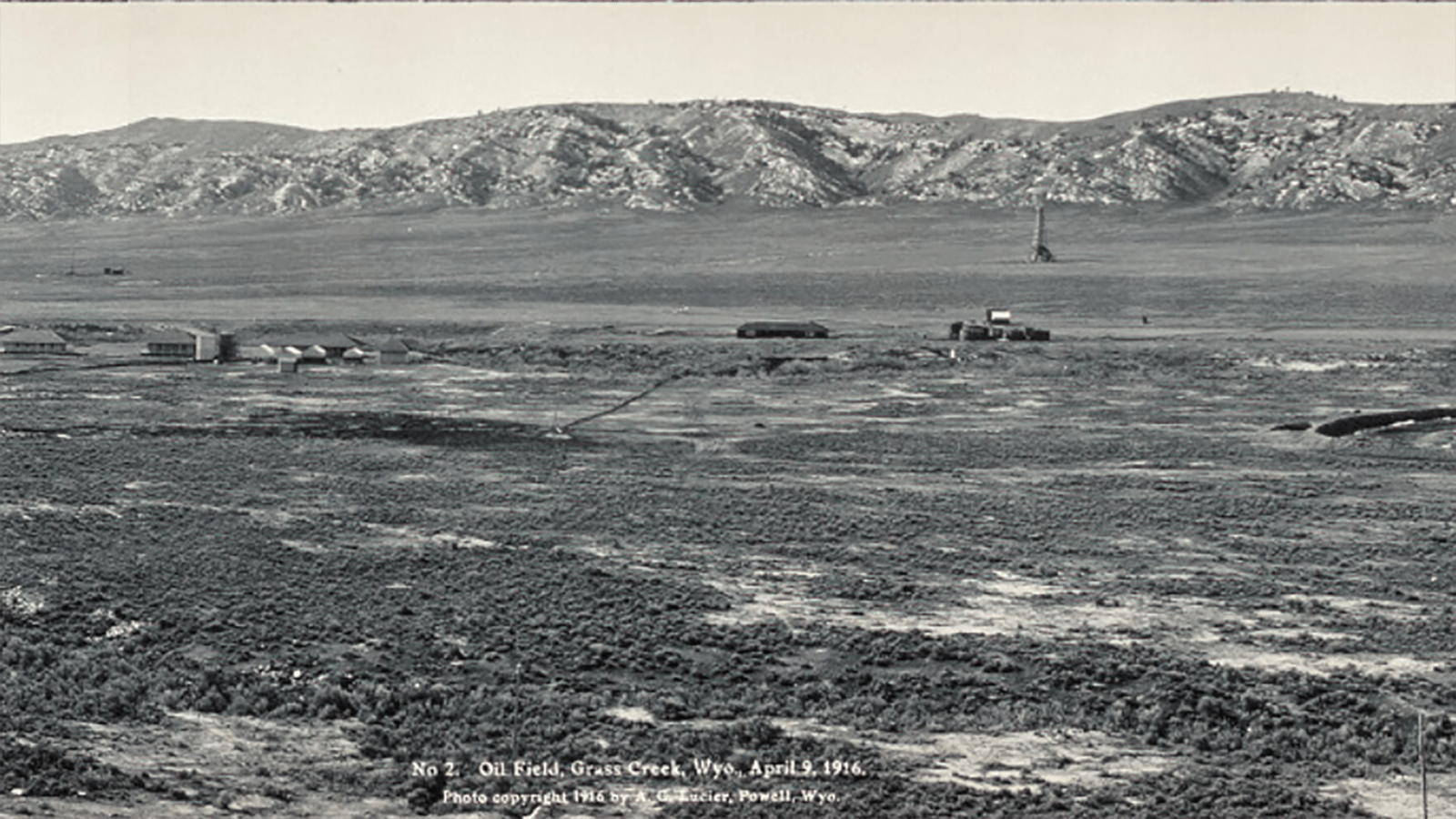

The Tulsa, Oklahoma Morning Times reported on May 23 that two more Independent Torpedo employees in Elk Basin were blown to bits.

The men were loading nitroglycerin in preparation for shooting wells for the Ohio and Midwest companies.

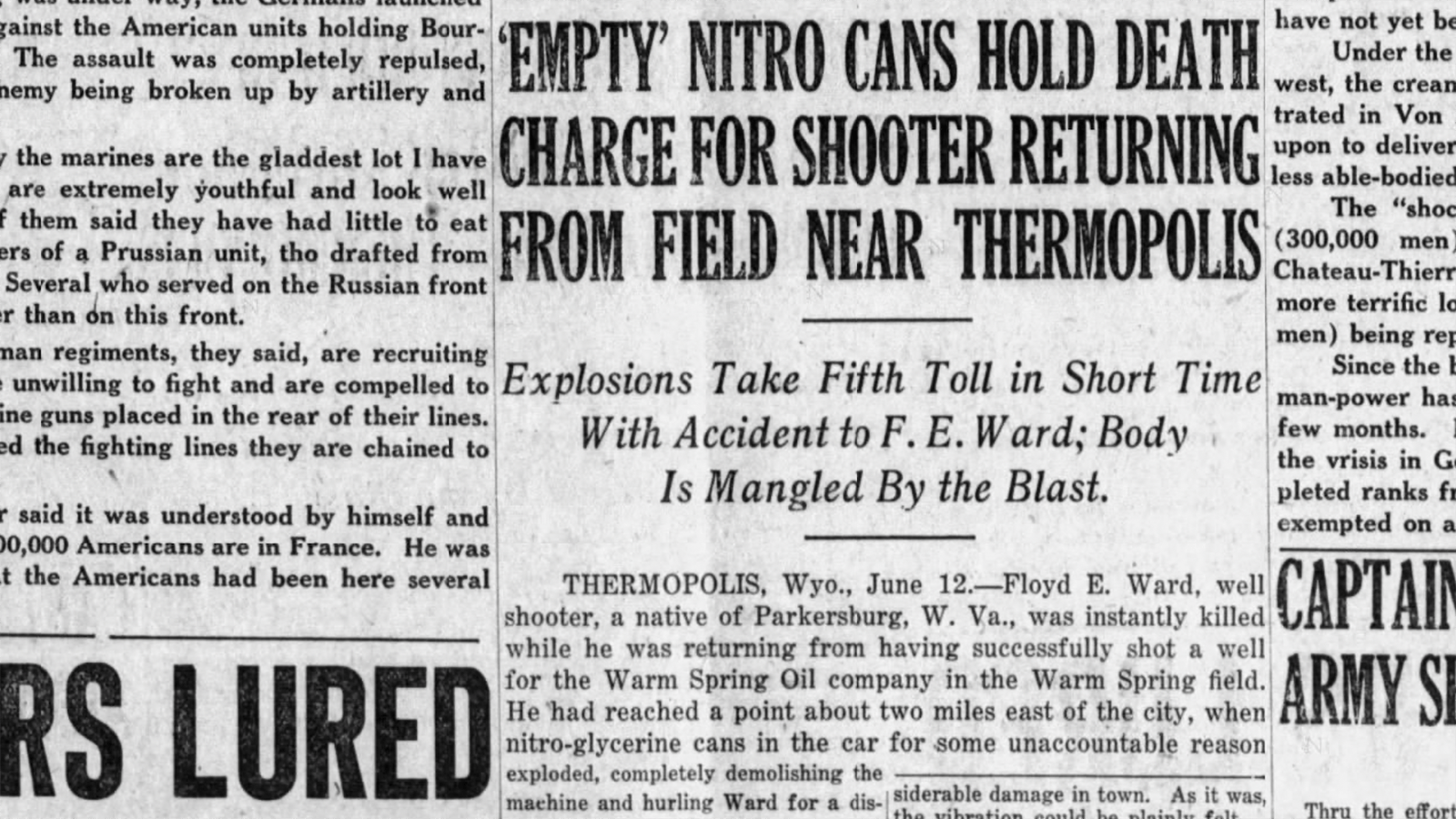

On June 12, the Casper Daily Tribune again had a front-page story about the death of another young man sent to the state as a replacement for those who lost their lives.

“Empty Cans Hold Death for Shooter Returning From Field Near Thermopolis,” the newspaper reported. “Floyd E. Ward, well shooter, a native of Parkersburg, West Virginia, was instantly killed while he was returning from having successfully shot a well for the Warm Springs Oil Company in the Warm Spring field.”

Ward’s car was 2 miles east of Thermopolis when the explosion blew his body and car parts into pieces, hurling him 200 feet. Parts of the car were found 500 feet away with the front tires undamaged and the rear tires of the vehicle completely destroyed.

University of Wyoming’s Department of Energy and Petroleum Department Head Soheil Saraji said the use of nitroglycerin torpedoes goes back to the early days of the oil industry in the late 1800s when the explosive liquid was used to frack rock.

“When you do that, your production improves,” he said. “There are a lot of dangers with it. Nitroglycerin is unstable and it has a ton of risks for transportation and handling. And then when you do the explosion down in the hole, you are not in control.”

Mini Quake

The dangers of the job were not lost on the men who signed on to work for the nitroglycerin company or those communities affected by the blasts.

On May 7, 1918, the explosion that took out the Independent Torpedo Company’s plant three miles west of Greybull created a mini earthquake that could be felt miles away.

A rancher near Manderson, 30 miles from the site, reported that the shock was “plainly felt,” and in Basin, dishes rattled in the cupboards, The Big Horn County Rustler reported on May 10, 1918.

The blast claimed the life of W. W. Walters and C. E. Gerrard who also carried the nickname “Dynamite” due to his role as a well shooter.

“F. E. Borner, who lives but a half mile from the plant, says that there were three explosions, the first from the plant, the second from the magazine, and the third a smaller explosion," the newspaper reported. “He says he rode for a short time with Gerrard, who left him at his home and that he is sure that Gerrard had no more than time to get to the plant and get out of his car before the explosion took place.”

Greybull residents drove to the site to find the plant completely destroyed, a hole in the hill where the magazine holding stored nitroglycerin once existed, and Gerrard’s body horrifically mangled. The vehicle the company used to transport the nitro was in pieces.

An initial search for Walters found no remains of his body. The next day a piece of skull with black hair resembling Walters’ pate was found on a hillside above the explosion.

Both men had told people in town they were hauling nitro to a couple of well sites that day. There was an estimated 1,800 quarts of the explosive at the site.

Walters, a widower, left behind two children. Gerrard left a wife. Men who knew them said they had both been in the business for several years and that both had told others they were going to get out of it “next year.”

Danger Known

The Big Horn paper reported Walters told an acquaintance who warned him about the potential of dying in an auto wreck due to problems with his car that it wasn’t going to happen that way.

“I’m going to be killed by nitroglycerin,” he reportedly said.

Walters formerly worked for the Swanson Torpedo Company, and it had been in business for years, but with the Independent Torpedo Company’s move into the state, the firm had been sold to them.

Just a few weeks later in Elk Basin, near Cody, the Independent Torpedo Company had employees out of Greybull working to load a truck with 130 quarts of nitroglycerin for shooting a well when the truck exploded.

Cody’s Northern Wyoming Herald reported little was left of Guy Macklehaney and Earl Glenn when people responded to the blast.

“The largest part of the men was found about 800 feet away,” the newspaper reported. “The country around was thoroughly searched to find as much of the victims as possible but only fragments were found.”

Two men passing by in a truck were thrown from their seat. The blast was heard and felt in Powell and Garland, and the mantles of glass lamps were shattered, the newspaper reported.

Meanwhile, the June 12 explosion that killed Ward left a shaken Thermopolis community. Ward, 32, had a wife and arrived in Thermopolis to replace the other men who had lost their lives in the previous blasts.

“Mrs. Ward was stopping at a local hotel at the time,” the Thermopolis Record reported on June 6, 1918. “She had usually accompanied him on his trips to the fields but by chance was not with him on the fatal day. Although almost an entire stranger here, she has found friends in the persons of some of the ladies in town who have given her all comfort possible.”

The paper reported that Ward had apparently used the nitroglycerin and was just transporting the container in its holder when the car exploded.

The Lexington Herald in Lexington, Kentucky, on June 18, 1918, reported that the deaths and explosions brought an effort by the Wyoming government to bring the Independent Torpedo Company employees under the protection of the workmen’s compensation fund.

“The Independent Torpedo Company has not been contributing to the compensation fund and the heirs of the victims of the recent explosions therefore are not entitled to payments from the state’s industrial fund,” the newspaper reported.

Changing Workmen’s Comp

During the Wyoming State Legislative session in 1919, the Wyoming State Library website shows lawmakers amended their previous legislation, House Act 77, from 1915 and 1917 related to workmen’s compensation.

The definition of “extra-hazardous occupations” included the oil field and “all employments wherein a process requiring the use of any dangerous explosive or inflammable materials is carried on …”

The law stated “every employer engaged in any occupation therein defined as extra-hazardous is required to pay into the State Treasury for the benefit of the Industrial Accident Fund a sum of money equal to one and one-half percent of the moneys earned by each of his employees…”

The amended law was signed by Gov. Robert Carey on Sept. 25, 1919. Incidents that occurred before the revised law took effect were not covered.

Saraji said the oil and gas industry moved away from nitroglycerin in the past 30-to-40 years to more modern techniques. Now drillers use shaped charge perforators with small charges that are precisely engineered to pierce the metal tubing and open the formation to the well bore.

Companies also use hydraulic fracturing or acidizing techniques that allow for more control over the well versus just blowing up the bottom with nitroglycerin.

The university’s Richard and Marilyn Lynch Multidisciplinary Advanced Stimulation Laboratory also is focused on new techniques of hydraulic fracturing including the use of foam created by 90% gas and 10% water. Carbon dioxide and nitrogen are the gases being tested to create the foam.

“If our project is successful and we can replace water with foam, we can save 90% of the water (used) in a Wyoming gas well,” Saraji said.

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.