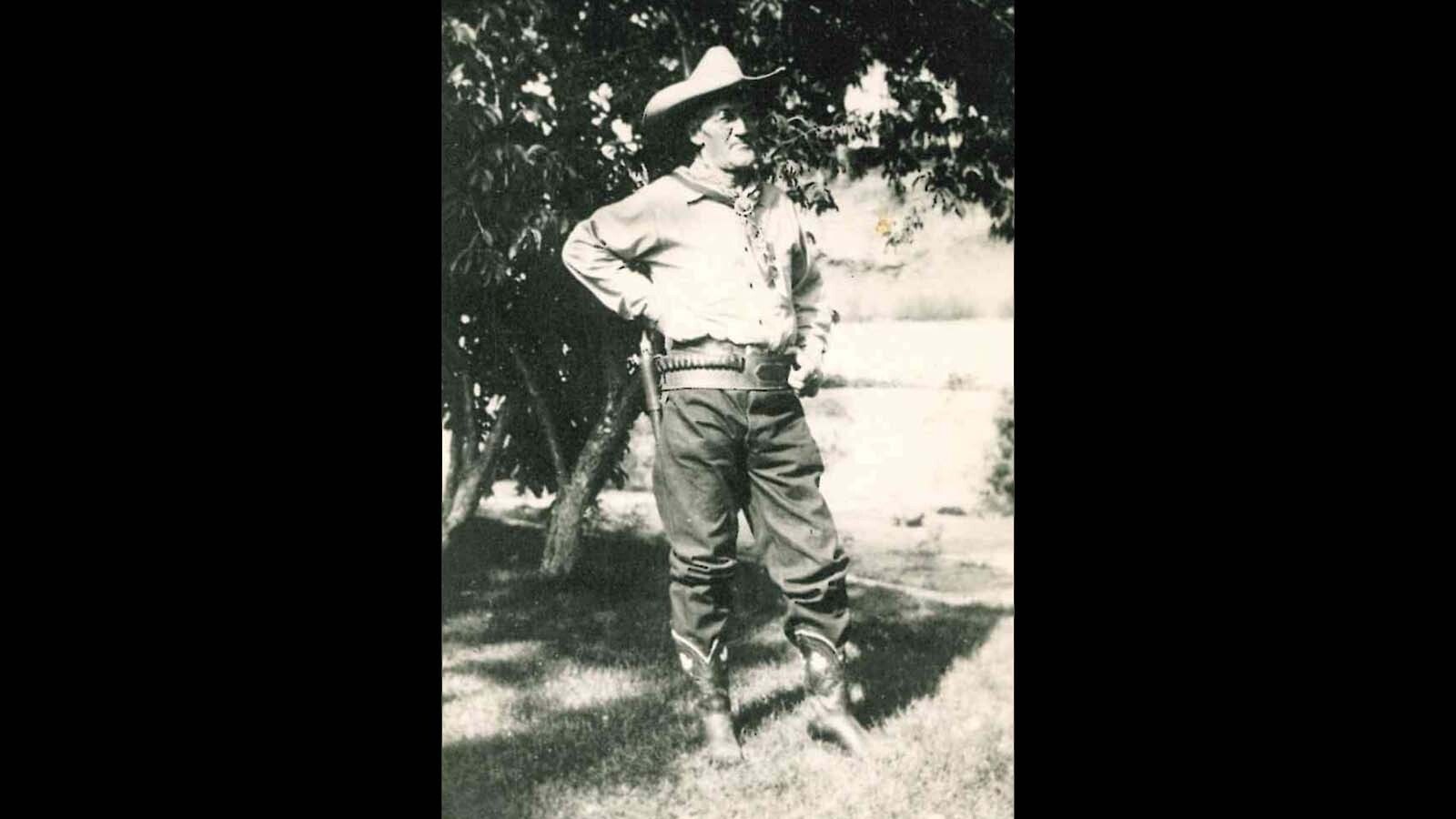

Dick Nelson arrived in the Black Hills by railroad and stagecoach in 1887 when he was 12 years old.

The Wyoming Territory was still a wild, lawless land, and since most of the prime land was already taken in Spearfish, his father Alfred Nelson headed into this wilderness, anxious to stake out his own land on the western edge of the Black Hills.

Dick Nelson’s great-great-grandson, Drew Hester, is keeping the family legacy alive in the territory and state his ancestors helped tame.

Hester works on the family land with his father as a fifth-generation rancher and wants to preserve the way of life his family has worked hard to keep for nearly 140 years.

And Dick Nelson had a front-row seat to the shootouts and loose Wild West attitude of the territory’s railroad towns.

“Dick came here in 1888 with his family, and they homesteaded outside of what is now Newcastle, Wyoming, today,” Hester said. “Their first house was a dugout on Oil Creek. Eventually, they moved and built a log cabin in Tubb Town.”

Hester grew up listening to family stories about his ancestor and the adventures Nelson lived through.

His great-great-grandfather had become associated with the railroad as a teenager and worked his way up the ranks for the next 45 years.

“Dick Nelson was born in 1875, lived to be 93 years old and died in 1969,” Hester said. “It's pretty amazing that my dad was able to know this Western pioneer cowboy railroad man and actually met the man.”

Over the ensuing years, Nelson was a witness to gunfights and hangings as he watched the railroad inch its way across the countryside.

In a 1965 letter, Nelson wrote about murders he observed from quick draw contests to recovering bodies that legendary lawman Joe LeFors had brought into town.

“I saw ranchman Eubanks shot and killed by one of his men he had trouble with,” Nelson wrote. “Another time, I was standing not over 10 feet away from Jess Freel and saw him shoot his Uncle Hank.”

Preserving The History He Lived

Nelson was a historian and recorded the early days of Wyoming, preserving what he lived himself.

“My grandfather Dick was just truly interested in literature,” Hester said. “It didn't matter if he was reading it or writing it.”

Hester has several handwritten notes and short stories that Nelson wrote about his time in Wyoming when he was in his late 80s and early 90s.

“He wrote about his life and stories that he knew that were true accounts of people he'd run into and gunfights and the whole nine yards,” Hester said.

One story his grandfather shared with author Elizabeth J. Thorpe was published in Bits & Pieces magazine in 1965.

It was the spring of 1891, and a 15-year-old Nelson was working for the railroad.

He was sent to man the commissary tent for the crews working on the branch line. They were in Irontown which later became Upton.

“The place was nothing but Billie Huff’s saloon, Club Foot Bill’s feed joint and Bill McKay’s load of hay he called a livery stable,” Nelson said.

The men rolled out their bedrolls in the sagebrush on the main street. During the night, they were awakened by fiddle music and shooting.

It turned out a wagonload of dance-hall girls had come from Newcastle, four girls and two fiddlers.

“We rolled out at sunup and as we passed the saloon, two cowhands came out with a girl between them,” Nelson said. “We heard one of them tell her she needed a bath.”

The cowhands steered the girl toward a well that supplied Irontown and threw her in.

“She hit bottom and came up headfirst,” Nelson recalled. “They pulled her out, her loose calico dress looking as if it had been glued to her body.”

Nelson and the railroad crew then went to get some breakfast, and one of the workers showed up with a bucket of water.

“We sat down at the slab board table and were drinking our coffee when one of the fellows suddenly said to the flunky, ‘Where did you get that bucket of water?’” Nelson said.

But they knew the answer before it came.

The water had come out of the town well.

“We finished our breakfast with neither more coffee or a drink of water and left,” Nelson said.

A Tough Breed

Nelson had started working first at a saloon then a sawmill when he was 13. By 14, he was working at the Cambria mine.

“When he was 15, he was employed by the commissary company that fed and supplied the railroad,” Hester said. “By the time he was 20, he was working for the Burlington rail line.”

Living this life toughened Nelson.

Nelson shared another story with Thorpe that illustrated just how tough one had to be as a teenager in the rowdy railroad towns.

The 15-year-old was working on the Moorcroft townsite when three cowhands from Texas arrived, each with two guns strapped low on his hips.

Nelson said that when they got a few drinks under their belts they started shooting up the town.

“Too bad there was no TV outfit present to take it in,” Nelson said. “They kept it up for three days.”

Nelson was walking to dinner one night and had to walk past the saloons where the Texans were entertaining themselves.

“As I passed Scrub Peeler’s, two of the celebrators stepped out in front and saw me,” Nelson said. “One dropped a bullet about 10 feet ahead of me. As I didn’t stop or run, they put a couple right behind me.”

Saloon owner Peeler came out, spoke to them and they stopped shooting.

Peeler later told Nelson he told them, “You can’t scare that kid. He was born right here in Crook County under a tarp in a cow camp.”

“While that wasn’t so, Scrub sure paid me a real compliment,” Nelson said. “He had these fellows bluffed, too. In all the shooting they didn’t fire a single shot inside his saloon.”

Back To The Railroad

By 1892, Nelson was persuaded by his dad to leave the commissary job and join him in ranching.

However, ranching didn’t hold any interest for Nelson, so he studied law and continued to work odd jobs until he finally returned to his true love, the railroad.

Nelson began as a brakeman and retired 45 years later as superintendent.

Throughout those years, he saw Wyoming go from a lawless land to a tamer version of itself.

“We wouldn't be here without the old timers,” Hester said. “Reading these stories just blows my mind because you have no idea the hardship that these people went through.”

Hester said that as he looks at the legacy of his grandfather, it shows how Nelson had helped put the rail line across the state and the stories that Nelson wrote to preserve the history of the Cowboy State.

“He was just the spirit of Wyoming,” Hester said. “Wyoming still to this day is full of pioneers getting up and working long hours every day to raise our families and put food on the table and stay humble and honor our traditions.”

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.