When the level-headed surveyor heard his employer wanted to reward him for saving the company thousands of dollars by renaming a train stop after him, he countered.

Edward Gillette asked the chief engineer of surveyors on the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad if the company would consider giving him a percentage of the savings that he accomplished in finding a new and better route to what was then called Donkey Creek.

In exchange, as an employee he would pay for all the surveying costs on that part of the rail line.

His boss’s answer, as recorded in the 1925 book Locating the Iron Trail, was like a loving pat on the head.

“He replied that we would get rich too fast,” Gillette wrote. “However, it was not so much a question of pay with us as to do good work and the company had our best efforts at all times.”

Despite the rejection, the Connecticut-born civil engineer would go on to do well for himself. He married the daughter of a Wyoming congressman, established a home and political base in Sheridan, and near the end of his career would serve as a respected state treasurer in the administration of Wyoming Gov. B. B. Brooks.

At the Rockpile History Museum in Gillette, Justin Horn, museum assistant in charge of collections and exhibits, said that part of the reason Gillette adorns the signs of the 33,500-person city today is because the railroad didn’t think much of the name “Donkey Creek Station" or "Donkey Town" as it was nicknamed.

Honored Man

Donkey Creek flows through the south part of the city. And in the late 1880s, Gillette arrived in the region as the railroad surveyed a route for tracks through northeast Wyoming.

“He came through as a surveyor and found the quickest way to build through the Powder River Basin,” Horn said. “So, that is why they named the City of Gillette after him as a way to honor him for finding a route for the railroad to go.”

Gillette would go on to have an opinion about the city bearing his name, but Horn said he is not aware of any special connection that followed between the city where the railroad arrived in 1891 and the man who saved the railroad from laying five miles of track and constructing 30 bridges over Donkey Creek. Those extra miles and bridges were on a previous survey crew’s route.

In a biography of her grandfather published in the Sheridan County Heritage Book in 1983, Virginia Kleitz Mosley wrote that Gillette, who was born in 1854, remembered he was playing ball in his yard when his family learned President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in 1865.

She shared that he graduated from Yale University with an engineering degree in the same month and year as the Battle of the Little Big Horn in June 1876.

Looking back at his life, Gillette wrote in his book Locating the Iron Trail that after college, he worked in 1878 on a United States Coast Survey party on Long Island Sound.

He later received an assistant topographer appointment with the engineering department of the U.S. Army as part of official U.S. surveys west of the 100th meridian. He was ordered to report to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

He had never been west of New York or Washington, D.C., and the “trip was quite an experience,” he wrote.

Wild Trip

In Missouri, he reported that a “political organization” that had nominated one of its members for Congress got on board. Whiskey was shared, demands were made on the candidate for a speech, then a song, and then things got crazy.

“Everybody was talking, shouting and drinking although they had about all they could carry,” he wrote. “The uproar continued and finally a few shots were fired through the top of the car.”

At El Moro, Colorado, the railroad ended and he took a stagecoach to Santa Fe. The stagecoach driver was drunk and shared that he had been at a Mexican dance, got into a fight and shot a couple of partygoers.

Then things got dark.

“There was a total eclipse of the sun, and we saw Mexicans crossing themselves, muttering prayers and chickens going to roost,” Gillette wrote in his book.

The still drunken stagecoach driver drove at a “break-neck speed around sharp curves in a canyon and sent the stage off the road,” according to Gillette, who had gotten up beside the driver because it had been too rough riding inside the stagecoach. He jumped off into a cactus as the stagecoach wrecked. The driver broke ribs as the horses pulled the stagecoach down the trail.

Being an engineer, Gillette was able to temporarily put a wheel back on the stagecoach, put the driver inside, and drive the stagecoach to the next station. He received free meals for his efforts for the rest of the trip.

In Santa Fe, the survey party had not arrived, but he became friendly with the territory’s leading politician, who was also the author of Ben Hur.

“Governor Lew Wallace, who was living at the hotel, kindly furnished me with everything I desired, and I had an enjoyable time until the party arrived from Fort Garland, the outfitting point, a week later,” he wrote.

Over the next decade, Gillette’s work would take him across hostile Apache territory and the desert Southwest, and then into Colorado as he worked for the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad.

Joining The Burlington

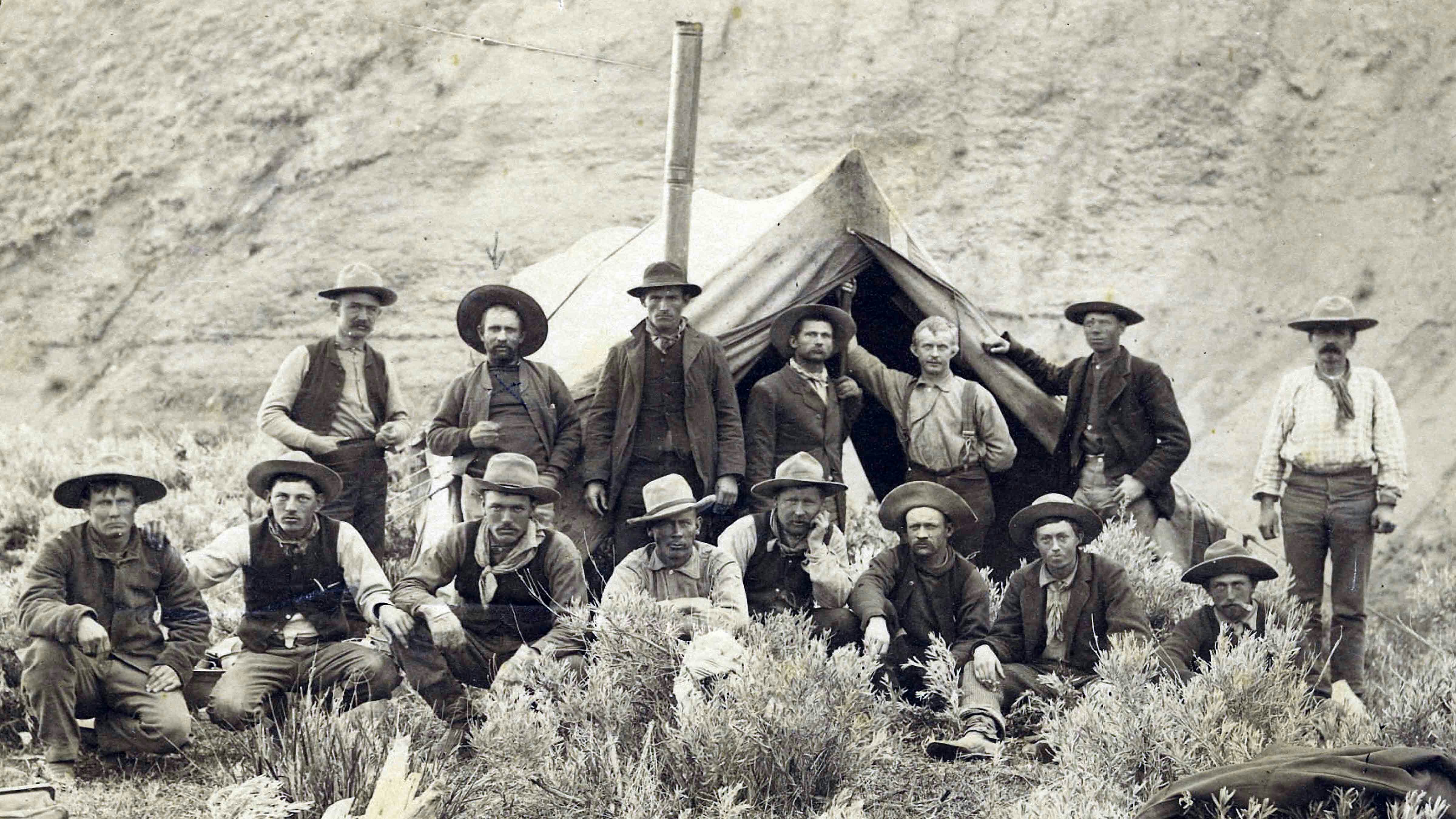

In 1884, he joined the Burlington and led a track locating crew through Nebraska, parts of South Dakota, and then Wyoming.

His work in Wyoming saved the railroad a lot of money. He rerouted an earlier survey line northwest of Newcastle as the contractor following a previous survey encountered a lot of rock that required more time and money to deal with.

Gillette identified a much cheaper route to construct and operate and saved a mile of track as well. For his efforts, he received a $25 per month raise.

The railroad, as it went through the region, gave Gillette freedom to try different routes than those identified through previous surveys. At one segment of the line, he saved the railroad $90,000 in construction costs.

His work around Donkey Creek and the savings he brought by finding a better and less costly route had him hoping for more money each month.

“The savings made by this new line were so great that we had some curiosity as to the action of the company,” he wrote. But after being told the town formed around the railroad would be named after him, he didn’t complain.

Gillette characterized the place where his name dwelt as a “live town from the start” due to cowboys and the proprietors of saloons, gambling halls, prostitution, and other vices who followed the railroad tracks across the West.

But as he wrote his book approaching the last decade of his life, he was pleased with its progress.

“Finally, it settled down to an orderly development and is now one of the best county seats on the railroad, in which the state takes much pride,” he wrote.

In 1890, Gillette surveyed the railroad line into the spot that would become his hometown, Sheridan. He believed the region had “more natural advantages than any locality we had ever seen.”

It also had a woman who would become his wife.

Married

In 1893, the then 39-year-old bachelor married Hallie Coffeen, 27, daughter of U.S. Rep. Henry A. Coffeen. The couple had two children, Harriet Sibley Gillette and Edward Hollister Gillette.

An adventurer during his railroad days, Gillette and a gold miner made a trek through Big Horn Canyon in March 1891, despite being warned that the 55-mile journey had never been accomplished.

“The few who had ventured to make the trip had perished in the attempt,” he wrote. His journey included measurements of canyon walls. On their last day, they had to use a rope tied to each other from the bank and crawl across the river ice because it was so thin.

His survey journeys included a side trek into Yellowstone National Park where at the “Old Faithful Hotel” he met Theodore Roosevelt, who had followed their horse trail through the snow to the inn.

“Roosevelt at that time was a civil service commissioner and had been recalled to Washington by the president,” Gillette wrote. His interactions with the future president included Roosevelt asking about his trek through the Big Horn Canyon.

When they parted the next day, a companion named Larry shouted: “Here’s to Roosevelt for President in ’96!”

“Too soon, Larry, too soon,” Gillette wrote Roosevelt replied. “As it was 1891 at the time, little significance was given the remark.”

In 1899, Gillette was asked to explore and locate a railroad for the U.S. government from the southern coast of Alaska to the Klondike. And in 1900, Gillette was made assistant superintendent of the Wyoming Division for the railroad.

Entrepreneur And Politician

Gillette left the railroad in 1905 and was involved in the construction of irrigation reservoirs in the northern part of the state and in helping sugar beet factories get developed in the region. In 1906, he opened his own general practice for civil engineering.

His business ventures included being named as an incorporator of the Heart Mountain Coal Mining and Milling Company along with others, as reported by the Sundance Gazette on June 15, 1894.

A Republican, Gillette served on the Wyoming State Board of Control and as superintendent of Water Division II in the state from 1901 to 1905.

From 1907 to 1911, Gillette served as the Wyoming state treasurer in the administration of Gov. B. B. Brooks.

His death on Jan. 3, 1936, was covered by several newspapers across the nation.

In Sheridan, the Sheridan Press editorialized on the loss of the man who brought the iron rail to the city and was instrumental in the development of the West.

“Sheridan would have remained a dusty little ‘cow town’ had not the ‘iron trail’ of advancing railroad systems pushed its way over the rolling hills into this sheltered valley,” the editor wrote. “Many other towns today are paying him homage as a far-sighted engineer, but to us, the residents of the community he called home … that deserved homage is overshadowed by the genuine sorrow in his passing. Edward Gillette was a man that a community can ill afford to lose.”

Gillette is buried in the Sheridan Municipal Cemetery in Sheridan.

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.