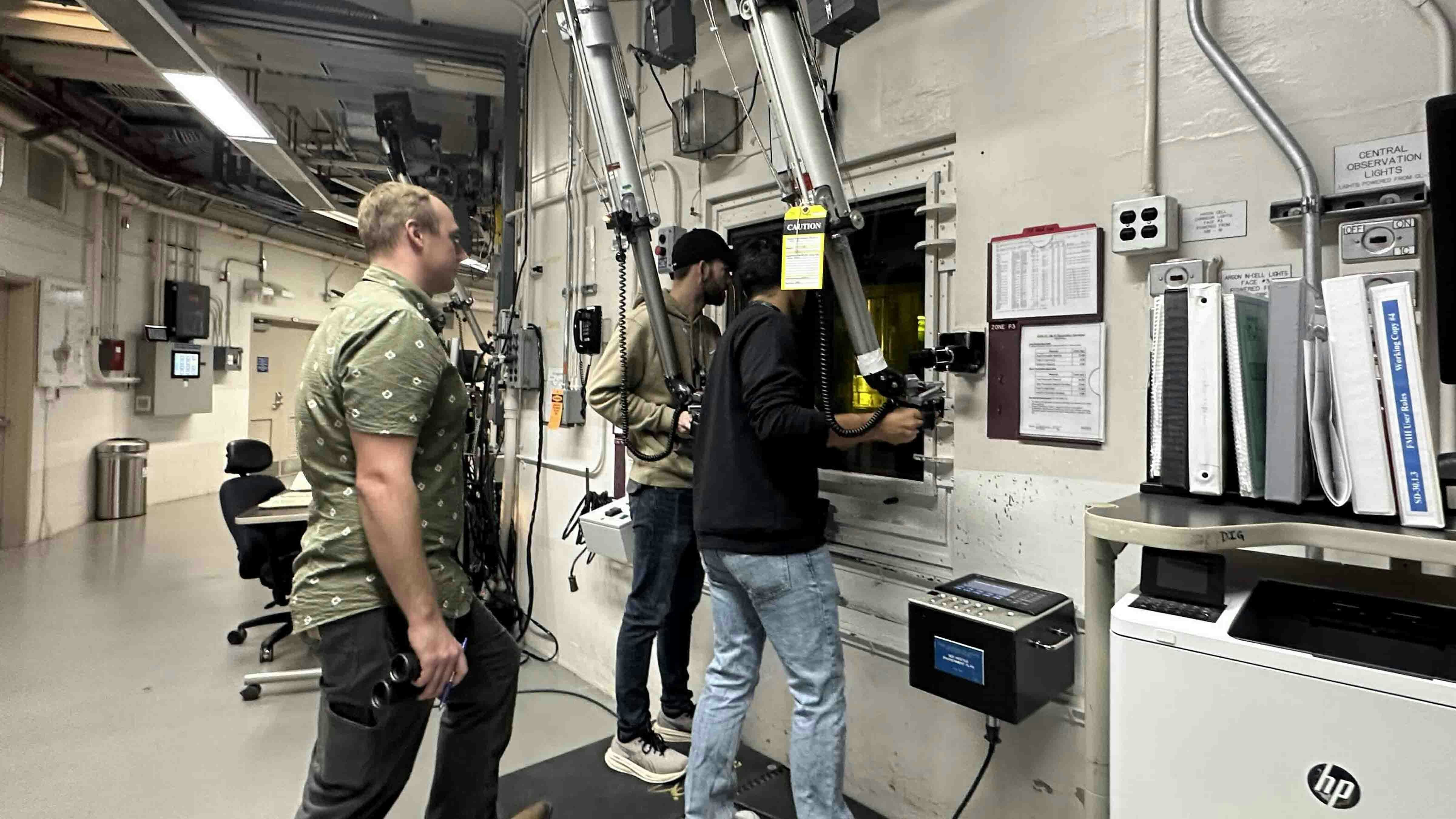

U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright took the controls of a robotic arm operating behind five feet of protective glass. He was at the controls of a high-tech version of an arcade mechanical claw machine. Instead of snatching stuffed animals and other prizes, this mechanical arm is designed to grip highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel.

As staff from the Idaho National Lab coached him along, Wright manipulated the robotic arm and gripped a spent fuel rod ready to be transformed into a type of fuel known as HALEU — High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium.

"That's pretty cool. You're picking up highly radioactive fuel rods," Wright said as he watched the robotic arm move spent fuel rods contained within a waste enclosure at INL's Fuel Conditioning Facility.

For Wright, the moment captured something larger — what he described during his Monday visit as the current "nuclear renaissance."

Wright didn’t use the word waste, calling it “fuel at the end of life.”

There are more than 200 types of spent nuclear fuel stored at INL, according to information shared during Monday's tour. The facility sits atop the Snake River Aquifer, and concerns about radioactive waste somehow contaminating underground water continue to animate opponents of the work and waste storage happening at INL.

As Wyoming communities recoil from nuclear waste — with some Natrona County residents opposing a proposed microreactor manufacturing facility and the Campbell County Commission recently passing a resolution banning the storage of high-level nuclear waste — the Idaho National Lab continues to embrace waste as an untapped resource.

In an interview with Cowboy State Daily, INL Director John Wagner framed the waste question as a policy decision informed by science and safe storage.

"I would say nuclear is the only energy form that accounts for every single gram of its waste material and has it in a safe and secure place, even as we've been running for over 60 years," Wagner said. "And so we have it safely stored. It's secure. Now the nation needs to make a policy decision. Do we recycle it or do we dispose of it in a geologic disposal like what was proposed at Yucca Mountain?"

Yucca Mountain, Nevada, was on course to become the final resting place for high-level nuclear waste, but it was scuttled during the Obama administration around 2010. The U.S. currently has no place identified to replace Yucca Mountain, and so INL remains home to lots of highly radioactive waste.

Recalling Wright’s experience controlling the robotic arm to pick up spent fuel rods, Wagner said, “It looked like a clean metal rod, right? It doesn't look like green goo or any of that.”

Wagner described how, “We chop those rods up, and then we dissolve them and we separate the uranium.”

Wagner added, “I don't want to say nuclear waste is a non-issue, but nobody is being harmed. We have it completely where we know it is. None of it is leaking out.”

“We know engineering and technically how to deal with these materials,” said Wagner. “But we do need a policy decision on how the nation wants to move forward using those materials.”

Robot Masters

The INL staffers running the robotics are known as manipulator arm operators and they undergo extensive training, INL Ambassador Taylor Wilhelm told Cowboy State Daily.

Wilhelm explained that the low-light yellow glow of the waste containment space where the robotic arms operate is brightly lit inside. But the light is muted by the thick protective glass.

“The lead that can block us from the radiation that's coming out is also blocking light that's coming out of there. So, we see about a 70 percent reduction in light coming out of that,” said Wilhelm. “The manipulator arm operators working that equipment are highly specialized. They're incredible because obviously you can't go to school and learn how to do this. This is all on the job training for these guys. It takes about 18 months before you feel pretty comfortable with it."

"They're working on taking that fuel, used fuel, turning it into a feedstock of new fuel for advanced reactors," Wilhelm added. "They're showing that that's possible."

The facility's history stretches back to the Experimental Breeder Reactor II, which Sarah Neumann, INL media affairs lead, discussed during the tour.

"The Experimental Breeder Reactor II was here. And so that reactor operated for, I want to say, like 20 years. It used to power all of this whole complex," Neumann said. "And then in the Clinton administration, they decided, 'Hey, you know what? We know everything we need to know about nuclear. We don't need that reactor anymore.' And they decommissioned it."

"And so, after they decommissioned it, the lab's mission changed quite a bit,” she noted. “And it went to kind of a cleanup mission.”

Now that mission is evolving again.

"There's just been this resurgence where people are like, 'Wait a minute. You know, nuclear seems like that's a really good way to do things because it's baseload power. It's not as carbon polluting as some,'" Neumann said.

From Waste to Resource

The HALEU being produced at the Fuel Conditioning Facility is enriched for use in U.S. advanced reactors, and that fuel is now heading to some of the country's nuclear developers.

On April 9, the Department of Energy announced conditional commitments to provide HALEU to five companies TRISO-X, Kairos Power, Radiant Industries, Westinghouse Electric Company and TerraPower.

"The Trump Administration is unleashing all sources of affordable, reliable and secure American energy — and this includes accelerating the deployment of advanced nuclear reactors," Secretary Wright said in the announcement. "Allocating this HALEU material will help U.S. nuclear developers deploy their advanced reactors with materials sourced from secure supply chains, marking an important step forward in President Trump's program to revitalize America's nuclear sector."

Steven Petersen, a spokesman for INL, clarified the connection between the work being done with robotic arms at INL’s Fuel Conditioning Facility and this broader initiative.

"The HALEU being produced at FCF… is indeed part of the HALEU that DOE is distributing to the companies,” said Petersen, noting there are other sources of HALEU.

INL’s HALEU production is one example of how DOE is supporting and subsidizing the U.S. nuclear power industry.

During a panel discussion at INL on Monday, Wright outlined the Trump administration's approach to energy subsidies by pointing to what’s contained in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

"We cleaned out a ton of subsidies, over a half $1 trillion of energy subsidies, the wind and solar, for example, 33 years running — that seems like enough," Wright said. "And in there are tax incentives for eight years for nuclear and geothermal.”

Wright continued to beat the pro-nuclear drum, stating, "Nuclear really is emerging. For the second time, it emerged in the ‘50s. It thrived for about 25 years, and it's been smothered for 45 years. So, there's some tax incentives as well. If you put shovels in the ground and start building something in the next eight years, so it's not forever. We don't want it to be forever. It's just to get an industry moving again."

A Dissenting Voice

Not everyone is celebrating INL's mission and its role in leading the charge toward a future where significantly more electricity is generated by nuclear reactors.

Nuclear waste watchdog groups like Idaho's Snake River Alliance point to all the waste piled up at INL as a real problem, especially given the lab's location on top of the precious Snake River Aquifer, which feeds into the Snake River and ultimately the Columbia River.

Hannah Smay, board president of the Snake River Alliance, told Cowboy State Daily, “The story when it comes to waste in Idaho is that there is a bunch of abandoned nuclear power waste just sitting in Idaho National Lab with nowhere to go.”

"We've gotten burdened with this super long-lasting toxic waste that has no permanent repository in the U.S. And so INL, which is not a suitable site, has become the de facto nuclear waste dump for a lot of the nuclear power waste, including all of the reactor waste from the nuclear navy,” she said.

And the prospect of a nuclear renaissance? Smay has heard it before.

"There's been a promise of a nuclear renaissance since the 1950s," she said. "It's a false promise."

As the leading voice for nuclear skepticism in Idaho, the Snake River Alliance has been sounding the same alarm for decades.

"We've been talking since the ‘70s. So, we've seen the same story happen over and over," Smay said. "Oh, there's a new nuclear renaissance. Oh, that's too expensive. It's just like a broken record at this point."

David Madison can be reached at david@cowboystatedaily.com.