Jack O’Rouke had been living on the Marshall Islands for more than a year preparing for this moment.

It was 1968 and the U.S. government was about to launch its antiballistic missile answer to Russia’s ICBM warheads that could fly 4,000 miles to their target.

It was the Cold War and O’Rourke was part of the effort to protect America from attack.

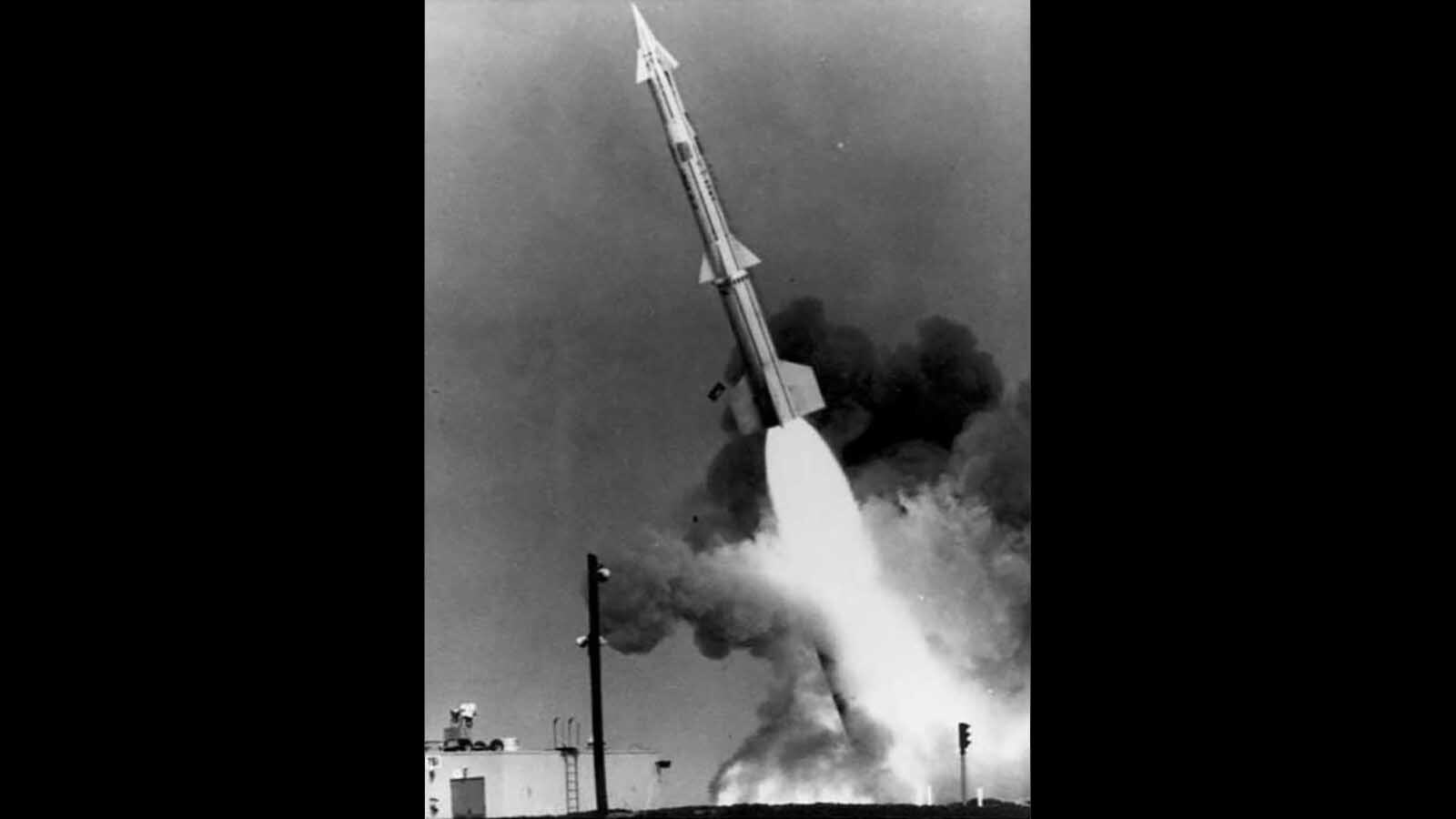

The LIM-49 Spartan was designed to intercept attacking nuclear warheads from ballistic missiles at long range.

A 5-megaton thermonuclear warhead was planned to destroy the incoming ICBM warheads, but the test missile had a dummy warhead.

It was still an awesome sight for a young man from Wyoming on the front lines of America’s next level of high-tech defense.

“It was really fun when they launched them, because that sucker just rattled the ground,” O’Rourke said. “We fired 18 while I was there and only three failed.”

O’Rourke, the son of a forest ranger in Buffalo, had just graduated from the University of Wyoming with an electrical engineering degree.

The Vietnam War was underway, and he had just passed his physical for the draft when he heard of an opportunity to work for McDonnell Douglas.

“I was highly motivated because it was a defense job, highly desirable in 1966,” O’Rourke said. “I did not want to go to Vietnam immediately, so instead I went to work for McDonnell Douglas on their missile program.”

O’Rourke got in right at the start of the program in L.A. and was put to work on the engineering team assigned to design the missile's telemetry system, which measures all the test data on the device.

The Test Site

After working on the missile system design for 18 months, O’Rourke was selected to go to Kwajalein, part of the Marshall Islands. His job was test the missile design in the field.

For a year, the team of engineers continued to work on the missile prototype and their calculations without launching the missiles.

During this time, O’Rourke was able to secure family housing and flew home to the states long enough to marry his sweetheart, Mary, and fly her black to the Marshall Islands.

She was soon hired to buy supplies, and they lived in “Silver City,” the silver trailer houses on one end of the tiny island.

“It was real interesting work,” O’Rourke said. “Once we got the missile developed and they got the radar system developed, they could launch missiles out of California at the Vandenberg Air Force Base, which is a typical downrange Russian ICBM distance of 4,000 miles.”

O’Rourke worked in a building they called the bay. Since the island was too shallow to dig a bunker underground, concrete and dirt were built up to protect the missiles.

“We built a launch cell up so that when we loaded the missile, we loaded it down inside this built-up mound that would replicate an underground cell,” O’Rourke said. “We had an office building where all of us worked out of and the bay where we did our electrical checkout was a few hundred yards away.”

The control center was in another building used to set up for launching.

As an engineer, O’Rourke was not authorized to pick up a wrench or a screwdriver.

He could use the test equipment, but he couldn't do anything else because there were inspectors who would monitor anything he ever touched on the missile.

“We put stuff on the missile in order to monitor every imaginable parameter such as vibrations, accelerations, current and voltage,” O’Rourke said. “We had somewhere around 400 channels of information.”

Launch

It was a fairly small program by aerospace standards, said O’Rourke.

There were only three electrical engineers at the test site on Kwajalein and the entire team was about 30 people.

Before the missile could be launched, O’Rourke had to test all the circuits and make sure that they were working properly.

“My job on the island was to test the telemetry system, which was state of the art at the time,” O’Rourke said. “I helped design all the parameters to measure everything on the missile and knew a little bit about everything on the missile.”

Prior to digital readings, the information had to be electronically transmitted. Telemetry, according to O’Rourke, was just another word for data that can be transmitted back to ground.

“We had three transmitters that were part of the telemetry system that transmitted all the test data back to the ground so we could see what was working and what was not working,” O’Rourke said.

During his time on the island, three missiles blew up out of 18, which O’Rourke said was a very good track record.

“We could look at the data and I knew which channels of information were going to go south first,” O’Rourke said.

Self-Explosion Safeguard

O’Rourke said that when a missile misfires, literally 1,000 different things could go wrong.

“On our missile, almost everything was redundant,” O’Rourke said. “So, if one little transistor failed, another system would back it up.”

On the three that ultimately failed, it was O’Rourke’s data that traced the issues so that they could be fixed on the other missiles.

“There were a lot of explosives packages built in to the missile to just pulverize the whole thing,” O’Rourke said. “Particularly, they wanted to destroy the guidance system in the warhead section in case it started getting off course, or we lost control of it.”

The safeguard was in place so that the Russians would not get America’s technology.

“The ones we lost were out of sight when they blew and it took probably less than 10 seconds,” O’Rourke said. “The ones that self-destructed probably occurred somewhere around the 15- to 20-second range, so they were close enough so you could see it.”

It was strictly confidential back in the day, but the missile only flew about 250 miles and could be controlled through jet propulsion rather that typical airplane controls.

“It blew propulsion out the back of the fins so that the fins would guide it, even though there was no atmosphere out there,” O’Rourke said. “We wanted to get out into the atmosphere and pick up the Russian nuclear warheads before it got back in the atmosphere.

"That was the idea. Fortunately, we never had to use it.”

The Frisbee

The concrete bunker was made so that if one of the missiles blew up in the cell, it would minimize the damage.

“You had to keep it from destroying the world,” O’Rourke said. “We had residential areas and office buildings within a quarter of a mile, so if one of these things decided to go crazy, it would have been a mess.”

All residents knew when a test day had arrived so that they would be off the ocean and secure in their homes when the missiles were flying.

“They had to know what was going on so that nobody was out in the boat or anywhere close by,” O’Rourke said. “There was the danger of debris coming back over the island which on at least one occasion it did.”

The missile that came back taught the crew a valuable lesson.

The wind was blowing away from the island and pushed the missile upside down and the fins were on top.

“It came back onto the island like a Frisbee coming into the wind,” O’Rourke said. “It landed about a hundred yards from the launch center.”

The missile buried itself in the coral and made a dramatic impact.

“That was an eye-opener,” O’Rourke said. “If that thing had come down through the launch center where everybody was sitting, it would have not been pretty.”

After that, the launch team was more analytical about wind direction.

By the time the missile had been tested and was ready for use, the technology had become outdated and the missile was never used in defense against an attack during the Cold War.

“It would have been used to if the Russians had attacked us,” O’Rourke said. “The first thing they're going to do is try to knock out our offensive nuclear weapons and so our plan was to go out and shoot the missiles down before they come in.”

Despite never being used in true combat, the project was still valuable to America’s security, O’Rourke said.

Engineers continued to build on the technology that he and his small team had tested decades ago in the Marshall Islands to help protect America during the long years standing off with Russia during the Cold War.

Contact Jackie Dorothy at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.