When lightning flashed over the area of Blackwater Creek 35 miles west of Cody in the Shoshone National Forest on Aug. 18, 1937, an alpine fir 100 feet west of the creek became a matchstick.

Thousands of volts of heat and light unleashed from the heavens split the tree, creating wood shrapnel and starting a wildfire in a dry, heavily timbered area in the Absaroka Mountains.

For two days the fire slowly simmered, moving up a mountain slope and as winds hit it back down to the creek bottom.

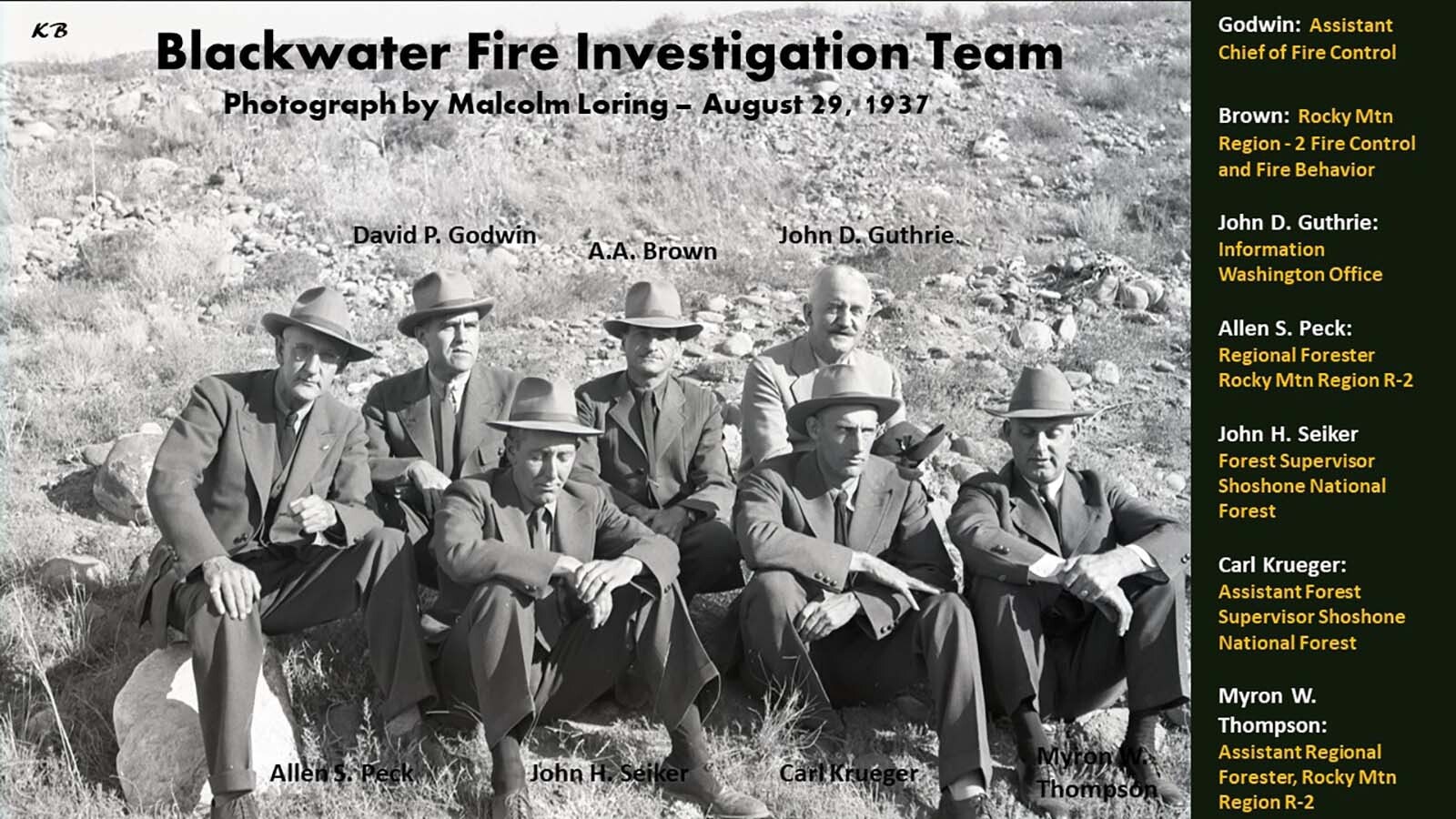

An official fire note penned by U.S. Forest Service Assistant Chief of Fire Control David Godwin dated December 1937 states that on Aug. 20, U.S. Forest Service Supervisor Carl Krueger flew over the area, saw the smoke and flames, and estimated the fire to be the size of two acres in the creek bottom.

By 3:45 p.m., the Wapiti ranger station had been alerted and Ranger Charlie Fifield headed to the area, first calling in Wapiti Civilian Conservation Corps members for manpower, eventually getting 70 men. He arrived at the fire around 5:10 p.m.

So began the incident named the Blackwater Creek Fire that remains the deadliest fire in Wyoming history, and the fourth worst in the nation in terms of lives lost.

“Forest Fire Takes 13 Lives, 40 Injured in Fighting Shoshone Flames,” the Casper Tribune-Herald headline read on Aug. 23, 1937.

In the end, 15 men would die, and 38 others suffered injuries.

Retired U.S. Forest Service forester, firefighter, and smokejumper Karl Brauneis, of Lander, has written a book about the fire called “The Blackwater Fire and the Men Who Fought It: How Firefighters Turned Tragedy Into New Beginnings.”

He said the fire proved instrumental in several ways in bringing changes to how fires were fought and its impact can even be linked to United States preparedness for World War II.

‘Slept For A Day’

Brauneis said the fact that the fire “slept for a day,” creeping along after the lighting strike, was common.

“It blew up on the evening of the 20th and they were calling for more men,” he said.

Communication during the fire was critical, and Brauneis said in 1937 that it consisted of a runner who would take a note from the fire scene to the main trail, where a man on horseback would get it to the Blackwater Lodge, which had a phone.

At 9 p.m. on Friday night, Aug. 20 the fire was estimated at 200 acres and Forest Service Supervisor John Seiker who arrived on the scene and Fifield believed the fire would not spread appreciably over the nighttime hours.

They were wrong.

Godwin’s fire note detailing the fire investigation said after midnight the wind picked up and the fire made it into the tops of the trees. More CCC men were ordered from the Deaver CCC camp, 50 men from Cody also were employed, and a request was made to the Tensleep CCC camp for men as well.

As Saturday progressed, newly arriving men were assigned to the fire line. Nearly 500 men from nine different communities mostly representing CCC camps were at the fire by Saturday afternoon.

“In those days there were no fire weather forecasts and what happened on the afternoon of the 21st of August 1937 was they got hit with a cold front,” Brauneis said. “There was no warning. They basically had the fire backing down the hill, and they thought ‘OK, we’ve got this.’ Things were looking really good.”

However, what most firefighters were unaware of was a second “spot fire.” Crews including Tensleep CCC workers who arrived Saturday afternoon were deployed to extend a fire line.

The 1937 fire note stated that the men did not know there was a “sleeping spot down in the hole” or that relative humidity was down to 6% as measured at Wapiti Campground at 1 p.m. on Saturday.

Drought Conditions

Brauneis said because of the drought conditions, the same conditions that brought about the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, timber was extremely dry.

At 12:40 p.m., the Forest Service supervisor noticed two strings of smoke from spot fires below the fire line being constructed and ordered those worked on. He did not see the spot fire “down in the hole.”

At 3:30 p.m. that spot fire in the hole “blew up,” the fire note stated.

Brauneis said a combination of factors including the shift of wind direction and the alignment of the slope and fire with the spot fire pushing up at the firefighters brought the deaths.

“Depending on where you were, you either got to safety or you got burned over,” Brauneis said. “Wind speeds were relatively calm until the cold front hit and then it shot right away to 30 miles an hour as it ran up the slope path.”

An Associated Press reporter in Cody for a story published in the Casper Herald-Tribune on Aug. 23, 1937, quoted Bureau of Public Roads foreman Earl Davis, who brought 50 men out of the fire as saying that the “wind blew flames at us faster than we could run.”

Davis led 40 young CCC men onto a rocky ledge and forced them to lie down. Some of the men panicked and ran and Davis and some of his men were burned trying to keep them out of the flames.

A man named Roy Blevans, a CCC worker from the Tensleep crew, but a native of Texas, was burned but told an ambulance worker: “God, how lucky I am.” Seven of his coworkers dropped in their tracks, burned by the flames trying to escape.

Blevans would die the next day in the hospital, the Casper Herald-Tribune reported on Aug. 24, 1937.

Also among the dead was U.S. Forest Service Ranger Al Clayton, 45, who was found with six others all in a straight line, burned as they kneeled on their hands and knees in the heat and flames.

“Al Clayton and a man named Post were two of the finest forest fighters we had, but they and their party of six were caught by a 40-mile gale as they worked up the mountain,” Seiker told a reporter. “They all ran for a rocky ridge, but the fire caught them and all found flat on the ground in the bare hope of escaping.”

‘Almost Cooked’

Seiker said somehow Post escaped, and he was sent to his home in Basin. The others among them “were almost cooked.”

The Cody community responded with residents volunteering to drive cars to haul the injured. Private houses offered to care for those less severely burned. Sheets and blankets were donated by those in the town.

Doctors from Cody, as well as two doctors visiting the region, hiked into the darkness to set up a triage and trauma station near the fire. A doctor from Billings and nurses from that city also traveled to Cody to help with care.

Ten burn victims from the fire, all CCC enrollees ages 17-18 years old, were sent to Cheyenne’s Fort Warren Hospital for treatment by train. Nine of the 10 were from either Texas or Oklahoma. One was from Sheridan, Wyoming.

Following his investigation of the fire, Washington-based Godwin wrote in his fire note that he “found no reason for criticism or organizational change.” He noted that the Tensleep CCC crew arrived later on Saturday than expected, and that may have had an impact, communication could have been improved, and locals who were anticipated to help with the fire did not arrive.

“On the other hand, it is clearly evident that this fire was handled in a manner reflecting sound experience and knowledge,” he said. “The placement and construction of control lines were well done in spite of rough terrain and bad fuel.”

Brauneis said another result of the fire a few years later was Godwin’s conclusion that the Forest Service needed to get men to fires faster. The Forest Service had been employing parachute drops of food to firefighters starting in the 1920s and 1930s, but suggestions about using parachutes to get men to fires were dismissed as too dangerous in the mid-1930s.

Smokejumping

But in 1939, Godwin would oversee an experiment in the Pacific Northwest region to test parachute jumping. That led to the first use of smokejumpers on fires in 1940 in both the Pacific Northwest, based out of Winthrop, Washington, and the northern Rocky Mountain region, based out of Missoula, Montana.

In June 1940, the U.S. Army sent Major William Cary Lee to observe parachute training in Missoula. That following Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940 using paratroopers. The U.S. at that time had no paratroopers or even a program.

Brauneis, a graduate of the 1977 smokejumper program in Missoula, said Lee adopted the smokejumpers use of static lines and reserve chutes.

“So, then you have implications of the (Blackwater Creek) fire going statewide to national, and into worldwide, with the adoption of those techniques into the Army paratrooper program,” he said.

Brauneis said in addition to the need to get to fires more quickly, the 1937 fire was also studied by a U.S. Forest Service chief in the late 1950s as he developed the 10 standard firefighting orders. Those included keeping informed on weather conditions, identifying escape routes and safety zones, maintaining prompt communications as well as others.

Brauneis, who published his book on the fire last year, said he has worked on filming a Wyoming PBS special on the fire that initially was proposed to come out next year.

“We actually packed in horses and got a drone in there and all of that,” he said. “It’s in the process of being worked on, but I think things are kind of in limbo right now with funding … we’ll just have to see.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.