Historian Mike Bell has studied Wyoming’s outlaws for several decades and has written several books about Butch Cassidy and the gang of horse thieves who roamed the Owl Creek region in the 1880s.

Part of the adventure of researching, according to Bell, is proving or disproving a story. That's what led Bell to uncovering the truth of Robert Parker, a man who was blown up in 1900.

Bell had come across a Facebook post by David Nickle on the "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" group page that claimed that the Robert Parker who was blown up by mishandling of dynamite in 1900, was in reality the outlaw Butch Cassidy.

Then just a year ago, the same rumor showed up in a YouTube video titled “Don’t Boil The Dynamite,” claiming that the producers had discovered a story with the potential of changing everything people thought they knew about the Wild Bunch, Buch Cassidy and the Western outlaw legend.

Namely, that Cassidy died in 1900 in an explosion and never even went to South America, where some historians believe he died.

“The debate about whether Butch died in South America or came back is a legitimate debate to have,” Bell said. “It's when somebody says, 'Not only did Butch come back, but he's this particular person' that I start questioning them.”

This pushback on myths resulted in a book, “The Counterfeit Cassidys,” that showcases Bell’s research into each of the men people claim was the infamous outlaw.

Parker, the latest myth Bell has explored, has a unique twist to his story.

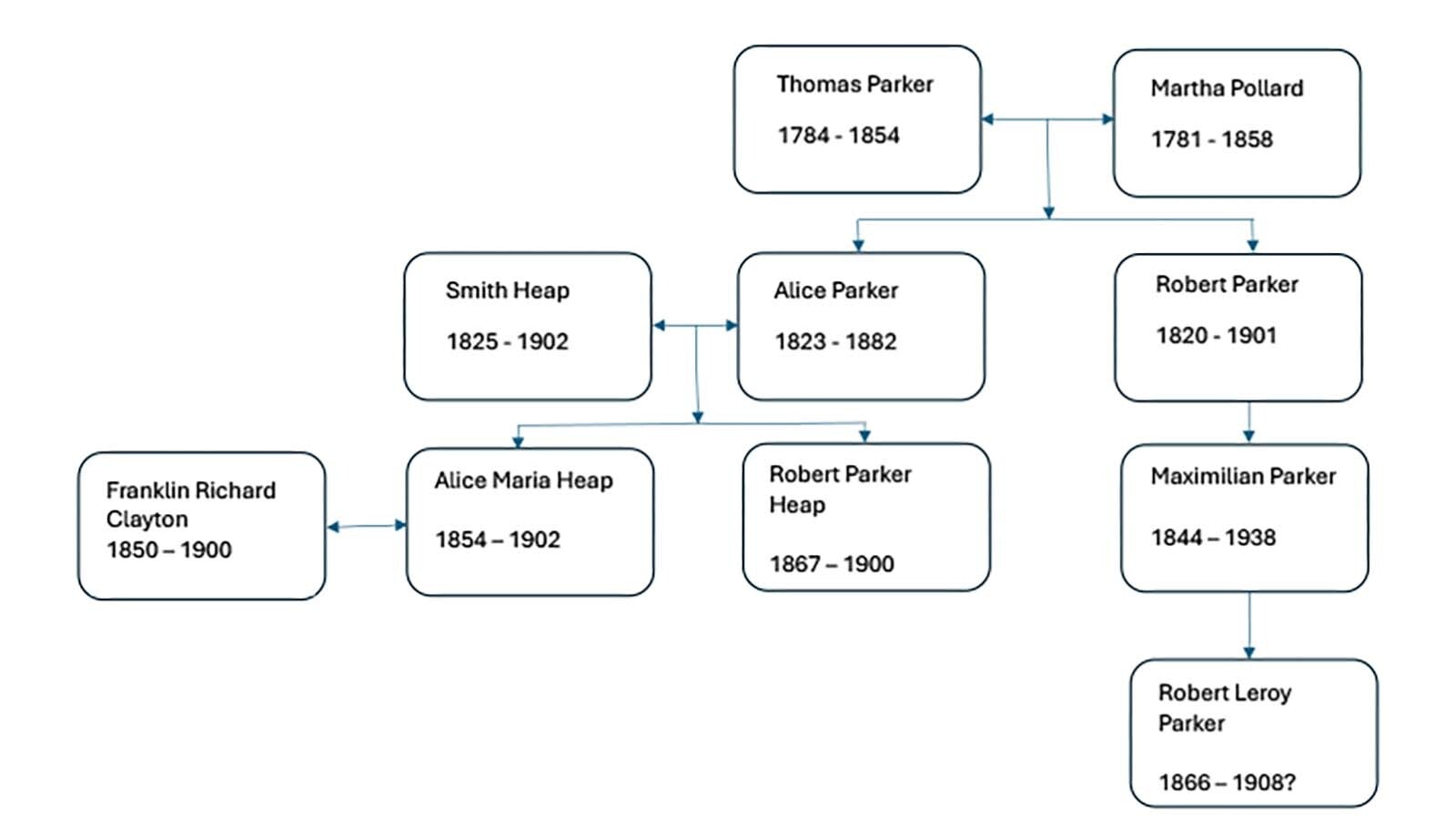

Parker is the only “counterfeit Cassidy” that is actually related to Butch Cassidy. They were first cousins, once removed and both descended from Thomas Parker and his wife, Martha Pollard.

They spent their early childhood only 15 miles apart from each other.

Both men are also named after the same man, Robert Parker, who was Cassidy’s grandfather and Parker’s uncle.

The real name of the accident-prone Parker is Robert Parker Heap, although he apparently dropped his surname and was known only by his first and middle name in Wyoming.

Explosive Combination

Parker had arrived in Laramie to work for the Union Pacific in the brutal winter of 1900. In January 1900, the U.P. needed to straighten out the sharp curves on their tracks and a gang of 60 men, according to the Laramie Republic, were tasked with reopening the gravel pits at Sherman Hill.

As Parker, as he was known, set to work, Bell points out that there is a theory that the men who robbed the Union Pacific later that year in August 1900, may have worked as part of this grading crews that were working on straightening out the railroad.

Whether or not that was the case, Parker himself would never live to see the robbery.

“It's literally freezing when the men get to work,” Bell said. “The job Robert and his crew have is to be blasting gravel out of a reopened gravel pit just south of Sherman Hill because they need gravel.”

The Union Pacific needed this gravel as a ballast for the new line they were laying to take out a great curve of the track heading north from Laramie to Medicine Bow.

“Robert is working with four other guys, and someone has the bright idea that to make the dynamite more effective, they should stick it in a can of boiling water and thaw it out,” Bell said.

The Weekly Boomerang reported that the five men were working in the west pit and thawing out four sticks of frozen dynamite by immersing them in a pot of warm water. It was said that they did not watch the pot carefully enough but allowed it to become dry and as soon as the dynamite touched the hot metal it exploded.

Eyewitnesses said that one of the men was thrown thirty feet down an embarkment by the explosion and all were hurled violently to the ground.

“If you let the dynamite touch the red-hot side of the tin can, the dynamite reacts and explodes, which is what happened,” Bell said. “Robert Parker Heap ends up in a heap by the quarry pit with part of his left leg blown away.”

The tin can had gone off like a hand grenade and Parker had bits of molten tin blown into his flesh.

Mistaken Identity

When the accident occurred a gravel train was waiting on the siding at Sherman, ready to come down the hill. The engine and caboose were immediately detached and made into a special train to bring the wounded men to Laramie, though some of the trainmen thought they should have been taken to Denver according to the Weekly Boomerang.

After an agonizing three hour wait for the surgeon, the injured men are taken to Laramie where the first two pass away within the first day. Parker hangs on but the effect of the amputation of his leg has taken its toll on him.

“He's taken down back to, um, Laramie and at some point, a journalist manages to get an interview with him,” Bell said. “The poor guy is delirious. He's been pumped full of morphine.”

Whether it was the pain or if he was already going by only his first two names, the newspapers all named him as simply Robert Parker, the same legal name as his outlaw cousin, Butch Cassidy.

“Sheriff Charles Lund puts a note in the press saying that this guy's been badly injured. He's not likely to make it,” Bell said. “Apparently, he was in such agony he begged for a pistol to take his own life.”

The news circulated in the press that Robert Parker had died, and the Union Pacific was attempting to find his family. All they knew was that he was from Beaver, Utah.

“Beaver, Utah is where Butch Cassidy, the other Robert Parker, was born,” Bell said. “So that gave rise to the supposition that this was, in fact, Butch Cassidy, the real Butch Cassidy, who'd been blown up.”

Not The Outlaw Cousin

When no one came forward to claim his body, Parker was buried in the Potter’s Field in Greenhill Cemetery. His age was listed as 32, the same age as Butch Cassidy.

Bell had scoured the newspapers for any more clues of the explosion and finally found a short note that had all the puzzle pieces falling into place. He finally knew who this mysterious Robert Clark was.

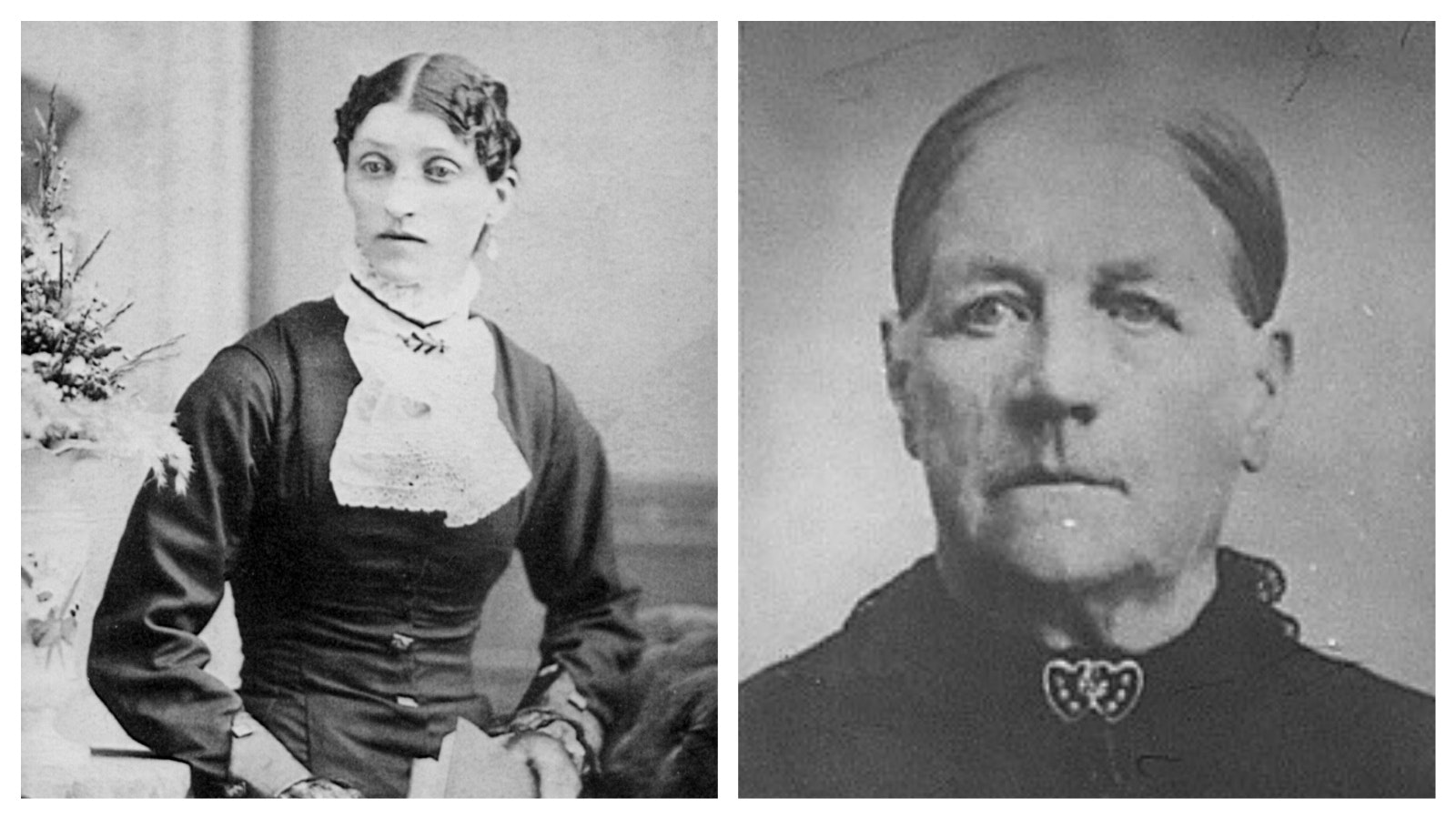

“A few weeks after the event somebody finally responded to the sheriff's note and that somebody was Alice Heap, who was the sister of Robert Parker Heap,” Bell said.

Alice had just lost her husband, and this caused her to either miss or delay in answering the post about her younger brother. She wrote the Laramie Press, identifying him by his full name of Robert Parker Heap.

“Once and for all, we can clear out the way the possibility that the man blown up was Butch Cassidy,” Bell said. “The heap family have pictures, and their Robert Parker is clearly not Butch Cassidy.

May Have Known Each Other

Bell is not done researching the fake Cassidy claims and has been trying to find more information on Robert Parker Heap. Especially any connections he may really have had with his more famous outlaw cousin.

“It's possible that the Robert Parker, who's knocking around the basin at the same time as Butch Cassidy, is this man who dies in the railroad explosion,” Bell said. “It's therefore possible that the two may have met each other by the time Robert Parker Heap blows himself up in February 1900.”

At this time, it is mere speculation on Bell’s part that the two met each other at some point in the Bighorn Basin but he will continue to hunt down clues to either prove or disprove the connections.

“We know that there's a Robert Parker rattling around in the northern part of the Bighorn Basin in the 1880s that is not Butch Cassidy,” Bell said. “He's a young cowboy working for Otto Frank, who had the Pitchfork ranch west of Meeteetse on the Greybull.”

This Parker signed a petition to put a bridge over the Greybull and then had a land claim in 1897, east of Meeteetse.

“He appears in the Fremont County tax records, at exactly the same time as Butch Cassidy, alias George Cassidy is also in the same tax records,” Bell said. “So they're clearly two different people, but they're in the same part of the Basin.”

Taken all the facts that he has dug up, Bell is firm that Robert Parker Heap is not the outlaw, although they are related.

“I say, somewhat flippantly, that the theory that Robert Parker Heap was Butch Cassidy doesn't have a leg to stand on,” Bell said. “Just like the real Robert Parker Heap, who sadly lost his left leg in the mining accident of the railroad accident.”

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.