When Stephen Tucker climbed to the top of the Hole in the Wall near Kaycee in Johnson County with Wyoming’s cowboy historian Clay Gibbons, it was to film a short tourism video for the county.

What Tucker saw as he stood on that legendary outlaw hideout rimmed in red rock not only took his breath away, it also blew his mind.

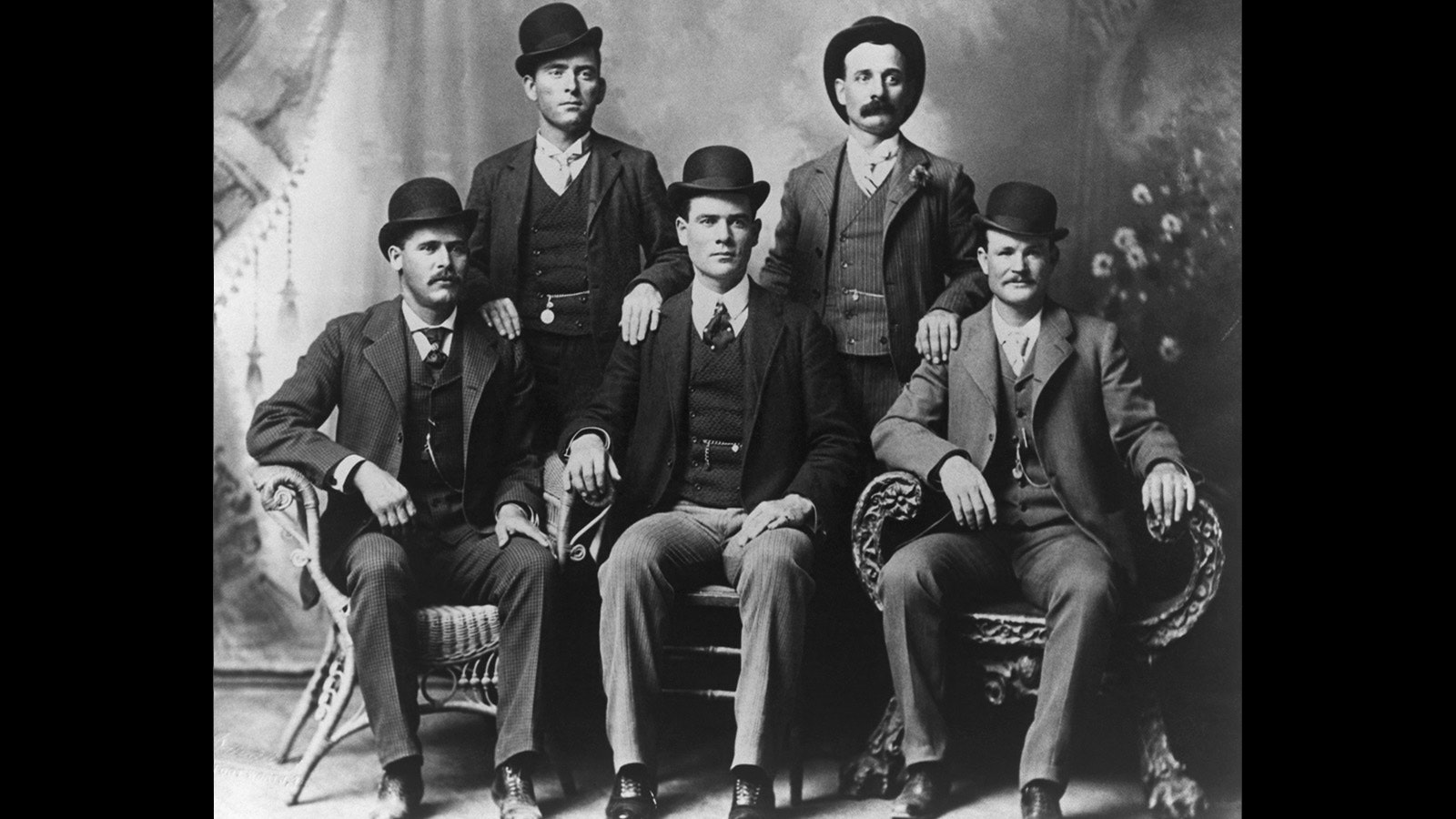

Here he was standing where some of America’s most infamous Wild West outlaws had no doubt also stood. Butch Cassidy, Flat Nose George Curry, and Black Jack Ketchum are just a few of the Wyoming outlaws who passed through this stunning and scenic hideout.

But he was also listening to cowboy historian Clay Gibbons spin the unbelievable, but true, Western stories of the Hole in the Wall in a way he’d never heard before.

It was a magical moment.

Gibbons made history come to life, and also hinted at other secrets and mysteries to discover in Wyoming.

It stirred up old dreams for Tucker of becoming a filmmaker. Right there on a sunny day in September 2023, Tucker stood on a precipice — not just the remote hideout that still had so many secrets to tell him.

“We got lost in the Hole in the Wall,” Tucker would later tell a small group of supporters gathered in Buffalo to watch a private screening of his recently finished documentary about the infamous outlaw hideout.

“We took a turn, and we ended up back in the late 1800s at Al Smith’s cabin,” he added. "We helped Butch Cassidy rob the Union Pacific Railroad. We taught Owen Wister how to ride before he wrote ‘The Virginian,’ and we even pushed back invaders with Sheriff Red Angus and Nate Champion.

“When we finally came out and made it back to civilization, we realized we had just come out of a portal. And that portal is the Hole in the Wall.”

Vanishing Window For A Dream

Sharing that legendary portal with others in a big way quickly became a personal mission for Tucker.

A 5-to-6-minute tourism video wasn’t going to cut it here. This was iconic American history, and the only way to tell it properly would be with authentic Wyoming voices.

“It just brings it back to our tagline,” Tucker told Cowboy State Daily. “Anything that happened in any Western movie happened here first. Owen Wister’s inspiration for ‘The Virginian,’ like the first real Western novel in our Western literature history, got his inspiration from Johnson County.”

The timing also was motivating.He quickly realized that he had a closing window to tell this story the right way.

“With aging historians and artifacts disappearing and all these different things, I felt like this could never be told this way again,” he said. “It felt like it was my duty, like my cinematic service. It became a personal mission to complete this in the name of vibrant American history and the culture of our state.”

The legends surrounding the Hole in the Wall seemed endless.

“The more I learned about this interesting history, the more I had to find out,” he said. “And with each local expert we interviewed, the scope of the project grew. It became more culturally significant.”

An Impenetrable Fortress Of Secrets

There are conflicting stories about how Hole in the Wall got its name.

There’s one story about cowboy Al Smith, who told people he got all his mail from a “hole in the wall.”

There’s another about a rancher named Moreton Frewen, who is supposed to have named it sometime between 1878 to 1885.

But the name had also appeared in Wyoming newspapers by the 1860s in reference to that location where outlaws were known to congregate with rustled cattle and horses.

That makes some sense, too, in the origins story. At that time, the word “hole” was broadly applied to any valley surrounded by mountains.

Some accounts claim there is only one way in and out of the Hole in the Wall, but there are actually two, according to Gibbons, who has studied Hole in the Wall extensively and gives private tours to the location.

The front door was a narrow, secret pass through the Red Wall of the sandstone cliffs. The pass is all but invisible to the naked eye from a distance, which makes it seem as if someone going into that pass has disappeared through a seemingly impenetrable wall.

That particular approach was highly defensible with a few men since it is a very narrow passage. Any posses trying to chase down an outlaw would have to come through one at a time. It would be easy to cut down.

The back door, meanwhile, was a secret trail over the mountains, rough and steep.

The higher elevation escape route could be used to quickly leave the area undetected. It was also the route the outlaws used to drive stolen cattle or horses into the valley until they could be taken to market in other states.

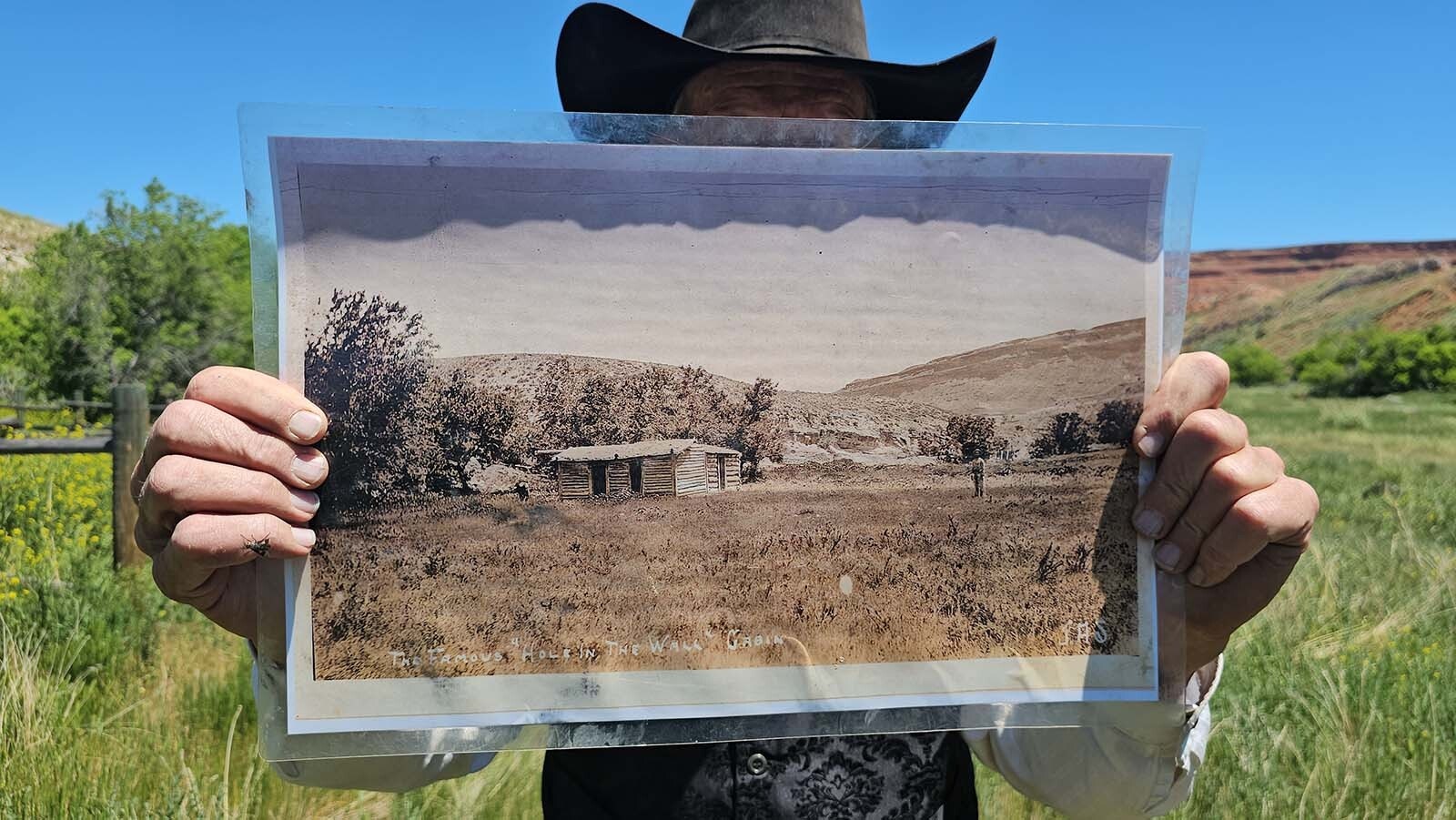

Cassidy’s Hole In The Wall Cabin Is In Cody

Cassidy had a cabin at the Hole in the Wall where he and his outlaw “Wild Bunch” would meet up, but the Hole in the Wall wasn’t his only hideout.

He had two others more frequently used.

There was Brown’s Park on the edge of Wyoming, Colorado and Utah. That the location touched on three states wasn’t lost on Cassidy, who knew that meant he could readily scoot from one state to another, depending on which lawmen were after him.

There was also Robbers Roost on the edge of Utah and Wyoming.

Cassidy’s cabin no longer hides in the Hole in the Wall. It was moved to Old Trail Town in Cody some time ago, where it is now part of a living history museum.

There are the remains of other outlaw cabins at the location, slowly giving way to time and weather.

Gibbons has a story to tell about each one, some of which illustrate how Hole in the Wall also sheltered dreams of a better life, not just outlaws.

Honor Among Thieves

The Hole in the Wall was in active use for about 50 years and was used by many gangs. No one gang was ever in charge of it, although there was a code of conduct.

One didn’t, for example, steal from anyone else in the Hole, and it was always best to mind one’s own business and not ask too many questions.

Each of the gangs built their own network of cabins and corrals inside Hole in the Wall, and each planned their own capers. It was rare to ride with another gang.

No lawman ever successfully entered the Hole in the Wall to capture outlaws during the 50-some years of its active use, nor did any successfully infiltrate it by going undercover.

Today, the Hole in the Wall is still extraordinary and remote, though it is no longer an outlaw hideout. It is part of Willow Creek Ranch.

There are public approaches to it, but those approaches are interwoven with private land, so a guide, either from the Hoofprints of the Past Museum or a historian like Gibbons, is helpful for those who want to find and understand it.

Elusive Dreams

Tucker took his tour with Gibbons in 2023, not long after moving to Wyoming in 2021.

His digital media business, however, had been launched in 2011 with an eye toward becoming a filmmaker.

It was a practical idea at the time. Tucker could support his growing family while also learning the tricks of the trade for what he really wanted to do, which was make blockbuster films and documentaries.

After about a decade, Tucker had built some great skills as he had planned. But the dream of making films was proving elusive.

“The road map to doing that independently, without living in Hollywood, without a bunch of money at your disposal, is just not (easy),” he said. “I’ve been trying to provide for my family while keeping an eye on what my passion is, without like giving up on myself.”

When Tucker took the Hole in the Wall trip, he was feeling restless inside. As he listened to Gibbons spinning out legendary tales of the West, he realized that this was a now-or-never moment.

“Either you’re going to do this or you’re not going to do this,” he said. “You can just keep making little commercial videos for the rest of your life, or you can go crazy for this year and maybe lose a lot of sleep and lose a little money but make something that is meaningful.

"Give it a chance and try for the filmmaking industry, because that’s where I’ve been headed my entire life.”

Losing money, he realized, is one thing. But losing himself? That was another.

More American History Told By Wyoming Voices Is Ahead

Regardless of whether Tucker’s finished Hole in the Wall documentary is picked up by a large streaming platform, Tucker has submitted it to all the major film festivals in hopes it can make a mark.

But he’s not waiting around to see the outcome.

He’s already thinking ahead to the next documentary and talking with Johnson County Tourism Association Marketing Director Toby Carrig about the possibilities for a series that would bring the Johnson County War to life.

He plans to use a similar approach as the Hole in the Wall documentary.

He wants to use authentic Wyoming voices to tell an iconic American West story, as well as authentic artifacts and local re-enactors like Nic Skalicky, who is an expert on life in the 1800s.

Skalicky played “The Outlaw” in the Hole in the Wall documentary, bringing all of his authentic costumes and props to the production, like the brothel coins The Outlaw shuffles in one of the documentary scenes.

Skalicky also brought along other re-enactors who could play roles like the sheriff or other outlaws and cowboys riding the range, all of whom have their own authentic costumes and props.

Tucker is realizing that Wyoming has plenty of iconic American history that he can bring to life with authentic Wyoming voices — enough to keep him chasing his biggest dreams for the rest of his life. But it’s also immensely satisfying to know he’s saving something that only exists here.

“I have all these skills that can finally be used for something way deeper and meaningful,” he said. “So it’s great to see things coming together.

Carrig believes both the Hole in the Wall and a series on the Johnson County War can really play into Johnson County’s biggest tourism strengths.

“The Hole in the Wall is a stunningly beautiful and undisturbed place,” Carrig said. “From the Red Wall to the Outlaw Canyon, and this documentary has some great visuals that reflect that. It’s also a place that offers unique recreational opportunities for camping, fishing, and hiking.”

All of that is showcased in an exciting way, Carrig said, one that he belies can draw more visitors to other parts of Wyoming besides Jackson Hole.

“The movie also provides some instruction that it’s wise to research the best way to enjoy the area,” Carrig said. “Seek out the tours from Clay Gibbons or the Hoofprints of the Past Museum if you’re looking for the history. Use resources from the Bureau of Land Management and Wyoming Game and Fish if you plan to spend time in Outlaw Canyon.”

Shorter videos are coming soon, which Carrig plans to use in tourism marketing campaigns to educate visitors about a legendary place, found in only one place in America, in Johnson County Wyoming.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.