Murphy’s Law is simple — if something bad can happen, it will.

In 1999, Jim Hand, dubbed the unofficial champion for the Laramie Chamber of Commerce, an attorney and owner of the game and puzzle company The Grail Inc., claimed Wyoming as the birthplace of Murphy’s Law.

The origin of the phrase is disputed, however. It is more commonly held that the phrase was the result of a miswiring mishap at a base in California in 1949.

That story, which wasn’t published until 1978, claims an unknown engineer made a mistake, and engineer Ed Murphy was heard to curse the technician by saying, "If there is any way to do it wrong, he'll find it."

Hand argues, and offers proof, that the Wyoming origin story of Murphy’s Law was published 93 years before the Californian version and is more plausible.

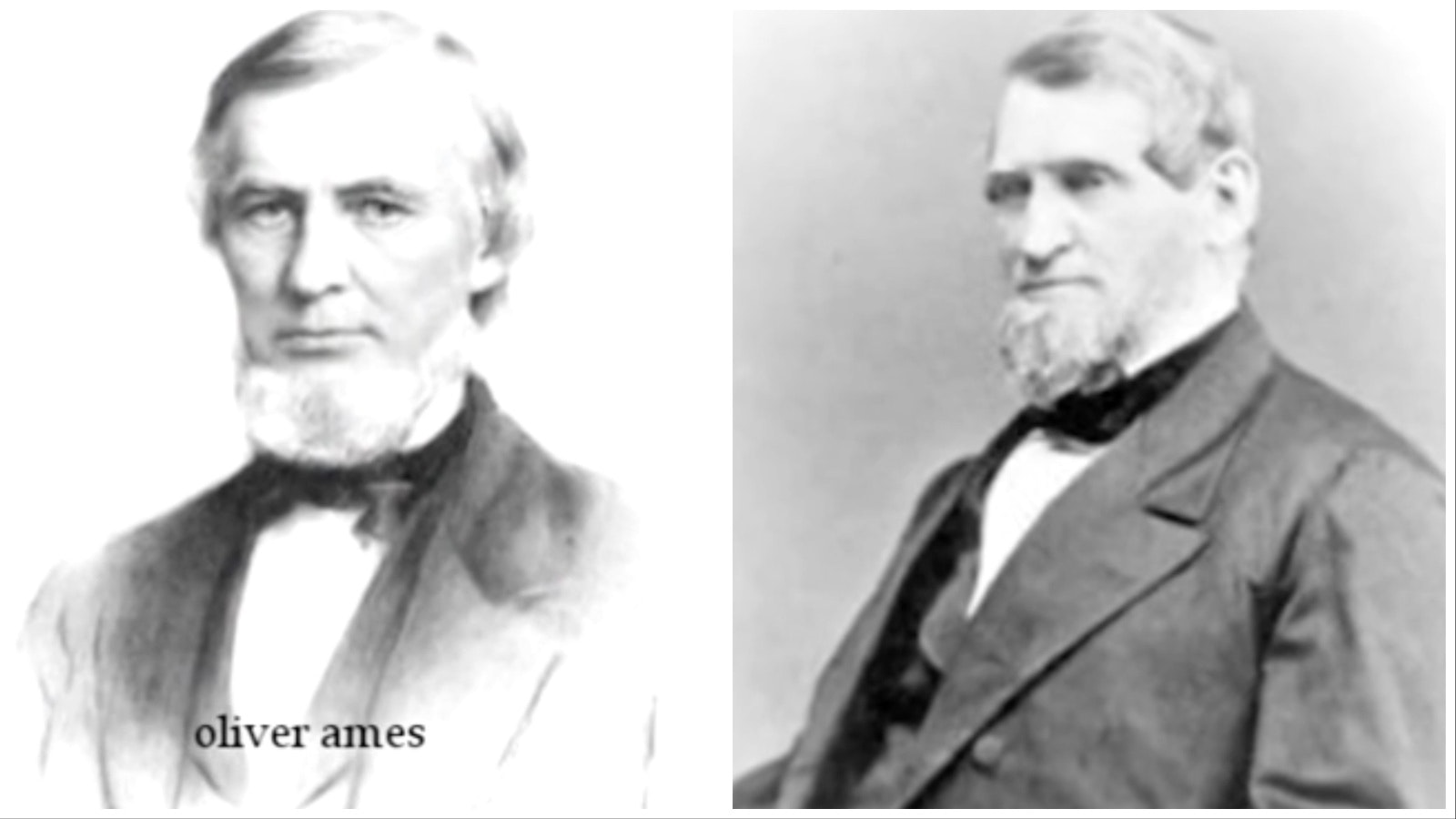

According to the Nov. 19, 1885, edition of The Weekly Boomerang, the Union Pacific Railroad Co. had just a few years prior spent $60,000 to build a monument of granite to the memory of Oakes Ames, a U.S. congressman, investor and businessman credited with being a major driver that helped build the Union Pacific railroad.

Many locals, the 1885 Cheyenne Daily Sun reported, considered the expensive monument “a pile of granite to gratify the vanity of the boss robbers connected with the Union Pacific.”

Hand claims that Murphy’s Law was born when an elected Justice of the Peace named "Billy" Murphy in Laramie talked to Albany County Surveyor W.O. Owen and learned that the monument had been built on "vacant" government land, not on a railroad section.

Murphy, according to Hand, was encouraged to file on the unclaimed property by Owen and received lawyerly advice from Edgar "Bill" Nye, the humorist andfounding editor of the Laramie Boomerang newspaper.

With their encouragement, Murphy went to the land office in Cheyenne and filed a Desert Land Homestead claim to gain legal rights to the land where the monument stands.

Following this legal move, everything that could go wrong for the Union Pacific had — the law was on Murphy’s side.

The residents of Wyoming celebrated the tycoon’s embarrassment and, throughout Wyoming territory and along the railroad route, dubbed the whole incident “Murphy’s Law.”

Judge Murphy

Known as “Billy,” Judge Murphy was well liked and ruled in many cases for the city of Laramie against petty criminals, collecting fines for disorderly misconduct and seen as a friend of the people.

According to his obituary from the 1918 Laramie Republic, Murphy was highly respected and bore a good name in the community, being honored by the people in the choice of an officer in the local courts.

Like many in the territorial lands of Wyoming, Murphy resented that the railroad received the best lands and was delighted to get the upper hand of the powerful Union Pacific at the urging of his friends.

Murphy’s Monument

The Weekly Boomerang of Laramie, edited by Nye, who was a fellow conspirator in the plot, ran the story under the headline: “Railway Rumblings From A Different Direction.”

Nye said that it was in September 1885 that Murphy, an upstanding citizen, filed a desert claim on the tract of land lying opposite Sherman station on the hill between Laramie and Cheyenne.

“The act was done in good faith,” Nye wrote in the Boomerang. “And with the understanding on the part of Judge Murphy that another railroad was shortly to put through there, over the hill, and that the site would be valuable to be converted into town lots.”

Murphy claimed only 40 acres, although Nye pointed out that he could have taken the full 640 acres to which he was entitled by law.

“It transpired afterward that the monument of granite, erected to the memory of Oakes Ames, who did such memorable service in the construction of the Union Pacific road, stood on the tract taken up by Mr. Murphy,” Nye added.

Murphy offered advertising space on his monument that the Cheyenne Sun had by then also named “Murphy’s Monument.”

He gave legal notice to the railroad company that its “rock pile” was trespassing on his farm and gave them a deadline to move it or lose it.

Lawful Claim

The embarrassed Union Pacific employees could not believe they had built and publicly dedicated their glorious monument on government land that Murphy now owned.

When they checked their legal rights, they were mortified to learn that Murphy could indeed lease advertising space on what was now his monument.

“The red-in-the-face railroad authorities realized that everything that could have gone wrong, certainly had gone wrong,” Hand said.

The contest for the possession of the ground in question became a quiet battle but caught the attention of the residents of Laramie who cheered for Murphy, although not openly.

They did not want the wrath of the railroad against them, according to Hand.

The Showdown

This monument that cost $60,000 had to be returned to the railroad’s ownership at all costs.

“The Union Pacific authorities naturally became alarmed at the turn of affairs,” Nye said in his 1885 article. “On last Sunday, Mr. Kennedy, of the land commissioners’ office; (John) A. Riner, United States attorney for Wyoming, and attorney (John) Symons, agent for the railroad lands in this territory, called on Judge Murphy to persuade him to relinquish his claims on the property in question.”

A fourth member of the party, according to Hand, was Nate Boswell, the former sheriff of Albany County.

“A top-level railroad lawyer was sent with a black valise, from Omaha headquarters to Laramie, with order to get clear title to the monument at any cost,” Hand said. “Murphy was tricked into meeting alone with the four powerful railroad negotiators who locked the door when he entered the room.”

Kennedy said they had learned that the judge had made a filing on the claim and that they were anxious to secure possession of the Ames monument.

“If the company had a claim on the property, why should they trouble the man who had made a bona fide filing?” Murphy asked, according to Nye.

“The object is to obtain a relinquishment of the claim in favor of the company,” Kennedy said.

“The company has the best land in the territory and that what they do not keep for their own purposes is transferred to other corporations,” Murphy said in his defense. “Nothing is left for the natives but rocks.”

Nye said that the response was then angry and not fit to print.

“Mr. Murphy,” Cheyenne attorney Rimes said. “You are taking a d---d big pile.”

“I’ve done the best I could,” Murphy said.

Murphy Is Kept Quiet

With their badgering, the four legal experts had frightened Murphy into thinking he had broken the law by filing a homestead on the land.

“They told him all the witnesses who signed his homestead claim could be charged with perjury,” Hand said. “They told Murphy he would surely lose his Justice of the Peace position, ruin his reputation, and risk prison.”

Then they switched tactics and promised Murphy they would try hard to keep the matter quiet and save him from all those troubles. He only had to sign a relinquishment of his homestead claim and promise to never tell anyone.

Their bluff worked.

Several propositions were made to Mr. Murphy for the relinquishment of his rights, and the matter was at length settled on a basis which shows that he had no mere mercenary interest in the property, Nye said.

“In fact, the committee may be thankful that they fell into such good hands,” the editor added. “Many a monied man would have given $5,000 or $10,000 for the relinquishment of the claim.

“Mr. Murphy was much easier to settle with, and it is evident that he was not seeking a money consideration, or he would never have accepted the terms which he did.”

In exchange of his valuable claim of the Ames monument, Murphy was given the deeds to two vacant residential lots on South 8th Street in Laramie that were worth about $385.

“Alas, mild-mannered Murphy later learned that the railroad lawyer had been carrying $15,000 in cash in his black valise to pay for the relinquishment, and had authority to pay twice that amount, if necessary,” Hand said. “Murphy had the law on his side and could have profited monumentally.

“Even for Murphy, everything that could have gone wrong, had gone wrong.”

Although the Union Pacific officials tried to keep the story quiet and kill it off, it lived on in the newspaper story and in the memories of those that laughed at how the railroad was publicly embarrassed by the well-liked “Billy” Murphy.

The Other Version

Hand said that the historic record shows that this is where the term “Murphy’s Law” came into use. It was not, Hand said, from an engineer in California in 1949 as popularly believed.

Ted Bear, Flight Test Center historian, claimed that Murphy's Law, “If anything can go wrong, it will,” was born at Edwards Air Force Base in 1949 at North Base. His article and claim were published in The Desert Wings, March 3, 1978.

Bear claimed that Murphy’s Law was named after Capt. Edward A. Murphy II, an engineer working on Air Force Project MX98 designed to see how much sudden deceleration a person can stand in a crash.

The 1949 claim was based on a minor incident involving the miswiring of a transducer.

According to Bear’s 1978 article, Ed Murphy was heard to curse the technician and say, "If there is any way to do it wrong, he'll find it."

The contractor's project manager kept a list of "laws" and added this one, which he called "Murphy's Law."

"Actually, what he did was take an old law that had been around for years in a more basic form of ‘if anything can go wrong, it will’ and give it a name," Bear admitted.

Based on even the historian not having historical proof of the story, the 1949 claim was virtually withdrawn, according to Hand.

Historical Proof

Hand said that historical fact is the proof that Murphy’s Law was born at the Ames Monument in Wyoming Territory and not at a 1949 engineering minor mistake by a nameless technician.

Wyoming's 1885 incident that happened more than 50 years before the miswiring, involved a Murphy who was directly connected with the laws and legal effects.

Hand said that the homestead claim on the expensive monument impacted organized planners and schemers and involved a significant, astounding historic happening.

“It was an incident which was itself characterized by the humorous maxim of something special and well-planned ended up unexpectedly and laughingly wrong, not just an irritating error with a humorless ending,” Hand said.

He also points out that the home lots deeded by the U.P. on Nov. 23, 1885, still exist in Laramie and on each lot is a modest 19th century-style frame house.

Murphy’s Legacy

“It was a great story,” Hand said. “Murphy paid his $9.75 homestead fee and, with the law on his side, got a good laugh, a good scare, and two residential lots worth $385, but also lost a fortune!”

The words "Murphy's Law," eventually became code for the story's moral, he said: "Everyone must expect, and accept in good humor, that whatever can go wrong, will go wrong.”

The legacy of Murphy was not forgotten in Laramie County even though Murphy quietly left soon after. When Murphy died in Texas in 1918, his obituary contained the story of the Ames Monument.

Before his own death in 2017, Hands advocated that Wyoming should lay public claim to the birthplace of Murphy's Law and celebrate one judge’s successful and humorous move against the railroad tycoons of 1885.

Jackie Dorothy can be reached at jackie@cowboystatedaily.com.