For a minute, Mark Corbett thought he might get away with it.

As he sped from the Alpine Federal Savings and Loan in Craig, Colorado, toward the Wyoming border with around $10,000 stashed beside him, he felt a brief sense of relief when he heard on the radio that police were looking for a suspect in a red Fiat with Oregon plates.

That wasn’t him.

Corbett, who has since legally adopted his biological father’s last name but back then went by Mark Farnham, was driving a tan Dodge as he barreled down the highway.

That brief fleeting feeling of hope, however, was immediately replaced by a sense of dread that this wasn’t going to end well.

Up until now, luck hadn’t exactly been on his side. In fact, a long laundry list of bad decisions and missteps got him here in the first place.

At age 24, it was safe to say that Corbett’s life had veered drastically off course, starting with a mounting pile of debt, fueled in part by a cocaine habit he’d picked up back home in college in Minnesota.

Corbett came up with a plan to leave school, kick his drug habit and move to Wyoming, where he’d read there was big money to be made in the oil fields. This was the early 1980s with sky-high unemployment and interest rates.

The trouble was that he lacked any mechanical skills and, after a six-month disastrous tenure on a rig near Rock Springs, he quit and headed to Jackson where he waited tables and tried to sell a coupon book that further put him into debt.

As Corbett would later write, he “was out of options, out of money, and the rent was due.”

As the financial pressures mounted, Corbett thought robbing a bank was his best option because he didn’t have it in him to tell his parents he was in trouble or to ask for help.

In his words, he’d gone from being “a college student, former military policeman and son of a police officer to a bank robber. A crook. Things would never be the same.”

Little did he know it was about to get much worse.

Pulling Over The Wrong Car

Waiting down the road about 20 miles south of Rock Springs was 26-year-old Wyoming Highway State Patrol Trooper Steve Watt. A three-year veteran, Watt had finally landed his dream job of being a state trooper, a goal he’d had since he was just a boy growing up in rural Upton, a small town in eastern Wyoming with a population under 900.

Watt wasn’t supposed to be working that day because he had a funeral to attend in the afternoon and had just planned to do a little light paperwork in the morning when the call came in that there had just been a bank robbery in Colorado with the suspect heading his way.

Because it was a short day, Watt hadn’t bothered to put on his bullet-proof vest for the first time in his career. It was March 18, 1982, a day that will forever be seared in his memory.

He’d been told to be on the lookout for a red sportscar, but when he saw Corbett drive by in a tan car, he decided to pull him over to see if he’d passed or seen the car authorities were looking for.

Corbett pulled over to the side of the road as Watt slid his patrol car behind him and started to get out of his vehicle. As he opened his driver’s door, shots rained in through the windshield with one hitting him in the left eye.

He tried to get his bearings, laying on his side on the front seat with his service revolver under his body, when he saw the barrel of a handgun pointing down above him. Corbett shot Watt four times in the left side before running back to his car.

Severely wounded, Watt managed to get out of the car and empty his service revolver into Farnham’s back windshield with one bullet hitting Corbett in the shoulder. Watt then radioed that he’d been shot and called for backup.

Troopers blocked the road 3 miles outside of Rock Springs, prompting Corbett to ditch the car and try to flee on foot with the money. Officers caught him in a field.

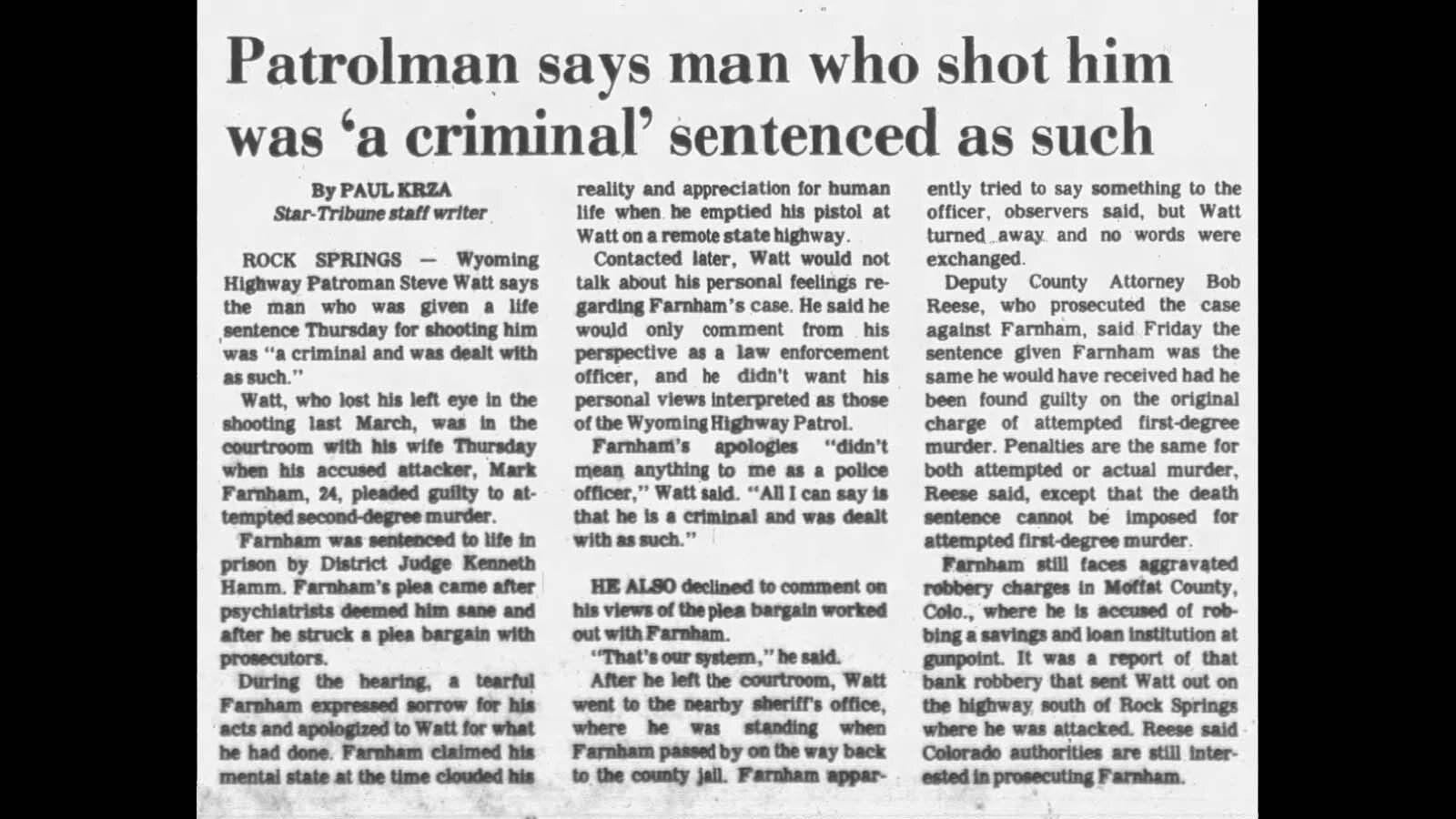

Corbett was charged with first-degree attempted murder, but ultimately, pleaded guilty to the lesser attempted second-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison.

Unlikely Friends

Looking back today, the two recount events of that day and what they now see as God’s hand in bringing them both together in ways that drastically altered the course of their lives.

For Watt this meant finding it his heart to forgive Corbett and becoming a Christian.

The fact that Corbett is now a free man after serving 41 years in Wyoming prison is largely owing to Watt’s forgiveness after having his sentence commuted by Gov. Mark Gordon in 2023 following the recommendation of the Wyoming Board of Parole.

Corbett is one of six inmates who have had their sentences commuted under Gordon since he took office in 2019.

Watt, for one, is happy to see Corbett free after years of trying to help his perpetrator get out of prison. This included attending at least 16 of Corbett’s parole hearings over the decades and lobbying on his behalf to every sitting governor, some of whom shaved years off his sentence.

Watt felt the weight of his guilt because he was responsible for Corbett getting a life sentence in the first place as opposed to the 10 to 20-year sentence offered as part of his plea deal. When the judge asked Watt if he wanted Corbett to serve life, he said “yes,” and that request was granted. TCSAR

Over the years, the two have forged an unlikely but close bond.

They’ve shared their story on many occasions to church groups, college classes and have appeared in a documentary together, “Unlikely Friends.” They were also featured in the 2010 book, “Shots Fired, Shots Forgiven: The Steve Watt Story” as well as numerous media articles.

Now 68, Corbett lives in Gillette where he works as a janitor at a coal mine and regularly volunteers with his church at the local soup kitchen. Though out of prison, Corbett will remain on parole until 2041.

Watt has since moved to Colorado but was in northeastern Wyoming in late May visiting family, where he met Corbett at Dalby Park in Gillette.

Sitting at a picnic table across from one another, the pair bantered back and forth and joked about what Watt would have to do to embarrass Corbett – a lot, it turns out – before the conversation turned toward transformation and how long it took Corbett to finally let Christ into his life.

Fighting Flashbacks

For Watt, the conversion came much sooner. But first, he had to overcome his intense hatred and anger toward Corbett, stemming from his injuries that ultimately cost him his career.

A big guy at 6-foot, 3-inches with an imposing frame, Watt’s left eye leaked a little as he squinted in the sun. He shifted on the bench from his latest round of hernia surgeries. At his feet is Sam, his service dog, a Labrador Retriever given to him by a former inmate in Colorado who trains service dogs and was touched by Watt’s story and his living lesson in forgiveness that ultimately changed his own negative views about correctional officers and cops in general.

Though his injuries have mostly healed, Watt still battles post-traumatic stress disorder that, in part, cost him his last job and first wife. He’s optimistic about his latest therapy involving brainspotting that seems to be working better than anything else he’s tried thus far.

It’s been a long, arduous process to get to this point, he told Cowboy State Daily, including about 20 surgeries over the past four years to reinforce the doctor’s earlier work following the shooting.

Along with losing his eye, doctors removed part of his liver and most of his intestines. One of the bullets is still lodged in his spine because it’s too dangerous to remove.

Tipping Point

Despite the lasting scars, Watt is an upbeat guy who revels in the ability to wake up every day and share his story of forgiveness and to ask as many people as possible – including this reporter – if they know Jesus as their lord and savior.

He thrives on this message, which he said completely changed his life.

Following the shooting, the physical pain was excruciating, prompting Watt to rely on alcohol and pain pills.

Then there were the dreams and PTSD that made it impossible for him to stay on the job.

His tipping point came one day months after the shooting. He had pulled a motorist over for speeding, and when the man went for his wallet, Watt went for his gun.

“He was only doing what I asked,” Watt said. “I knew I couldn’t do this job anymore.”

The incident led to Watt going on disability while he continued to work through the aftermath of his injuries both seen and unseen.

At the time of the shooting, he’d only been married to his first wife, Marian, for about six months. They were just two young kids struggling through it, Watt said, as they both grappled to find a way.

Watt recalled attending Corbett’s sentencing and shaking with rage as his hatred and bitterness grew like a cancer. He resented the life sentence that he, too, was given. He resented himself for not killing Watt when he had the chance.

As it stood, he’d waited until Corbett got into his vehicle per police protocol instead of shooting him in the back as he retreated.

Desperate for some relief, he went to see the police chaplain who suggested he try to forgive Corbett to which Watt said not a chance.

Power Of Forgiveness

Finally, Marian started attending church, which threw Watt. Religion, he said, had never been a part of either of their lives. She would come home energized on Sundays, talking to Watt about the power of love and forgiveness.

She spoke to him about forgiving Corbett for God, who forgives all men.

The message started to sink in. Slowly at first, but Corbett decided to go along with her to church. It wasn’t an instant transformation, Watt said, and he tried to lie at first to Marian and the pastor about having forgiven Corbett, until both called him out.

Finally, at the suggestion of Marian, Watt sat down to write Corbett a letter, telling him he’d forgiven him. He had no idea what to say, but with his pen poised over the paper, the words rushed to him: “Dear Mark,” he wrote, “I just want to share my joy with you. If you haven’t already, won’t you join me in Christ’s love.”

That was the release he needed. Watt immediately felt a sense of peace descend upon him as the anger and resentment lifted.

What followed in return was an 18-page letter from Corbett, apologizing and attempting to explain his life up to that point. The two continued to exchange letters, until later that year, when they met face to face when Watt attended a revival at the prison.

Watt recalled seeing Corbett for the first time standing there in his prison-issue blue jeans and white T-shirt, squinting up at him from behind his glasses.

He didn’t see a monster who’d shot and left him for dead, Watt said, but rather a guy like himself who had been struggling to survive, who’d gotten desperate and scared and hadn’t known where to turn.

“I wrapped him in a big bear hug,” Watt said.

In the ensuing years, the two would talk often. Forgiving Corbett cost him friends, Watt admitted, particularly those in law enforcement. Cops didn’t appreciate him taking a criminal’s side, something he said he understands.

Black And White

Up until he found Christ, Watt viewed the world in black and white. There was right and wrong and nothing in between.

As a lawman, he was firmly on the right side to the point where he once even pulled over his wife for speeding 74 mph in a 55 zone. To be fair, he’d already warned her once.

She gamely accepted it but asked him to cover it for her since he was headed over to the courthouse anyway. In the end, the judge dismissed it, while his sergeant told him he was jerk. Watt was upset no one took the law as seriously as he did.

Now, that guy is unrecognizable to Watt.

Today, he’s grateful his path crossed with Corbett because he wouldn’t be the same guy he is today.

After he stepped down from the WHP, Watt became a police chaplain in California before returning to Wyoming in 1992 where he took a job as a Sweetwater County Sheriff’s deputy in the public relations department.

He also served three terms in the Wyoming House of Representatives and was a member of the judiciary committee with an eye for judicial reform. Along with an unsuccessful push to repeal the death penalty, Watt was also outspoken about prison overcrowding and the cost of housing inmates both in and out of the state.

He didn’t introduce anything radical, he said, but he lobbied to provide an off ramp for inmates serving life or long-term sentences. His progressive judicial reform efforts fell on deaf ears in Wyoming, he said, including the financial arguments.

“People don’t care. They don’t want to think about that,” he said. “All they think is, ‘you committed a crime, and you’re going to do the time.’ … You don’t get elected for being soft on crime.”

Boom In Life Sentences

Just as Watt feels called to share his story about love and forgiveness, Corbett feels equally compelled to help other inmates like himself who are serving long-term or life sentences. As part of these efforts, Corbett founded a nonprofit, Compassion Wyoming, which advocates for providing an exit strategy for reformed long-term offenders.

Part of his mission, he said, is to let people know that people who do violent crimes can be rehabilitated and that the risk is low that they’ll reoffend once released.

“We’re building warehouses, and there's no exit strategy,” Corbett said.

The number of inmates serving life sentences, in turn, has skyrocketed over the past 40 years, particularly for those inmates 50 years or older.

In 1984, there were 93 lifers 50 years or older, according to figures from the Wyoming Department of Corrections. This includes those sentenced to life, life without parole, minimum years to life and those serving 50 or more years.

This number has continued to trend upward over the years, and in 2023, that there were 525 inmates serving life or long-term sentences, for a 400% increase, according to the same figures.

Meanwhile, the number of inmates housed in Wyoming prisons has also continued to increase slightly over the last four years. As of second quarter 2025, there are 2,510 inmates currently incarcerated in Wyoming prisons.

This is up over last year. In 2024, there were an average daily population of 2,261, a slight decrease over the 2,208 housed in 2023, according to WDOC’s 2024 annual report.

Accordingly, the average population in 2022 was 2,180, which was slightly up from 2,176 the year prior.

The average annual cost to house an inmate is $75,000 per inmate, according to a 2022 survey published by the Visual Capitalist using figures from the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Justice. This puts the state in the top 20 states that spend the most on housing inmates.

By contrast, Massachusetts spends the most on inmates at $307,000 per year compared to Arkansas that spends the least at $23,000 annually, according to the same data.

WDOC did not immediately respond to a request on what this figure is currently.

As it stands, prisoners sentenced to life in Wyoming have limited options for reversing their sentences regardless of what they do in prison to better themselves. And unlike California, Washington, Massachusetts and other states, Wyoming does not have any second-look or compassion laws that reassess sentencing for reformed inmates.

The one exception is that Wyoming has a statute that grants medical parole to inmates with a terminal illness.

Apart from appealing or challenging their convictions in the higher courts, inmates can request commutations that are reviewed by the Board of Parole. The board then decides whether to send a recommendation to the sitting governor, who can either issue executive clemency to reduce sentences or pardon crimes completely.

Remember Willie Horton?

Over the years, commutations have become increasingly unpopular, according to Dan Fetsco, who just wrote a book on the state’s history of commutations, “Cutting Life Short: A Second Look at Life Sentences in Wyoming.”

Fetsco has seen the justice system from multiple angles. He currently teaches criminal justice at the University of Wyoming. Prior to that, he was an associate attorney in a private firm, a public defender, a Carbon County prosecutor and executive director for the Wyoming Board of Parole for 10 years.

Fetsco researched the number of commutations between 1954 and 2019 and said commutations have increasingly dwindled into the single digits through the years.

In 1954, former Gov. Clifford “Doc” Rogers signed commutations for 34 prisoners out of a population of 272. By contrasts, during his term between 1955 to 1959, Gov. Milward Simpson signed 116 out of 298 inmates.

This figure remained consistent for the next four governors, but rose dramatically under three-term Democratic Gov. Ed Herschler, who signed 856 commutations between 1975 to 1987.

This figure once again plummeted to 218 under Gov. Mike Sullivan, who served from1987 to 1995, before grinding to a dramatic stop under former Gov. Jim Geringer’s leadership who only granted 15 commutations during his two terms from 1995 to 2003.

Fetsco said this dramatic decrease followed a national trend following George H.W. Bush’s campaign ad that portrayed his Democratic contender, Michael Dukakis, as soft on crime. Bush highlighted Dukakis’ support of weekend furloughs for prisoners, including those serving life sentences.

This included Willie Horton, who was serving life for stabbing a boy and killing him during a robbery, who went on to receive 10 weekend passes that ended after he fled and kidnapped a couple, stabbing the man while repeatedly raping his girlfriend.

“This all but killed commutations during that time,” Fetsco said, and those numbers have yet to bounce back.

Compassion Laws

Fetsco supports parole for reformed lifers and long-term inmates as does Lori Garrison, a member of the Wyoming Board of Parole, who joined in 2017 after being appointed by Gov. Gordon.

Fetsco, Garrison and Corbett recently spoke at the Association of Paroling Authorities International conference in Atlanta.

Garrison, who made it clear she speaks only for herself and not the board, said reducing lifers’ sentences impacts their desire for rehabilitation and their ability to succeed once released. Even if it’s just means shaving off a few years or giving lifetime inmates numbers to give them the hope of one day getting out.

“I personally feel that giving people the hope that they can eventually get out of prison gives them an incentive to better themselves,” she said.

This means attending college, participating in work release programs, attending treatment and other activities rather than feeling hopeless with nothing to lose, racking up disciplinaries and being unruly, she said.

She also sees both a financial and societal benefit in paroling long-term, reformed inmates – particularly those like Corbett whose victims are in full support – given the relatively low recidivism rates for long-term violent offenders who have been released.

According to a 2002 survey by the U.S. Bureau of Justice that tracked 272,000 inmates who were released across 14 states from their life sentences for homicide, only 1.2% were re-arrested on homicide charges within three years of release.

Another benefit to releasing older inmates, Garrison noted, is that it saves the state the burden of paying their medical bills as they get older and need hips and knees replaced or suffer other ailments like heart disease and cancer.

That said, both Fetsco and Garrison agree that there are some inmates who should never be released based on the nature of their crimes, unwillingness to show remorse or a lack of effort to improve themselves. Likewise, their victims need to also have a say in the parole process, and their word goes a long way in the board’s decision, Garrison said.

For those like Corbett, however, both believe that commutation should be a viable option given the state constitution’s purported goal that the penal code be framed around the humane principles of reformation and prevention.

Better Option

Corbett can attest to the fact that inmates like him who have been incarcerated for decades will do whatever it takes to stay out of prison.

He also feels personally responsible to provide Governor Gordon with bi-annual updates on his progress to ensure that he’s living up to his end of the bargain to be a productive member of society, including working, attending church and volunteering in his community.

His gratefulness to the governor is underscored only by his gratefulness to Watt, who not only forgave him, but became his staunchest advocate. He even formed close relationships with family, including his father, a retired police officer, who disowned Corbett following his crime.

It was a call from Watt to Corbett’s father that softened his resolve when he heard how Watt had found it in his heart to forgive his son.

Second Chances

Jeannie Miller, executive director of Second Chance Ministries, a Gillette ministry that provides assistance to those re-entering society from prison, believes in second chances.

She also knows a thing or two about faith and forgiveness.

In 2020, her 21-year-old son Tanner was murdered by his friend, who was charged with manslaughter.

Like Watt, she and her family chose to forgive her son’s killer.

“We took a stand,” she said. “We decided we would stand on our faith and stand for grace, forgiveness, compassion and mercy because we want Jesus honored.”

She learned about Corbett from a pamphlet about he and Watt that she’d found while cleaning her desk, and decided to write him a letter.

Miller found his story inspiring and wanted to tell him that he and Watt’s story helped her in her own grief and forgiveness.

The two exchanged letters until his release in 2023, when he landed at the ministry’s House of Hope, which provides temporary housing for inmates while they get back on their feet.

When Corbett arrived, Miller gave him clothing and a hygiene bag and took him to Walmart for the rest of the things he needed.

A trip to Walmart is jarring for anyone released from prison who isn’t used to colors or crowds of people and used to constantly looking over his shoulder, she said.

That was a really hard experience, Corbett remembered. There’s the color overload, the crowds of people. Almost as hard as figuring out how to navigate a cellphone after four decades of technology passed him by.

Miller was there for him and later was impressed with Corbett’s attitude and constant positivity. At every house meeting, he would recite a list of positive things he saw other residents doing over the week.

“Everything he does, he does with intention,” Miller said. “A lot of that comes from the mistakes he’s made, but he wants to make a good impression in the world coming out of the negative.”

Getting A Person Out Of A Criminal

For Corbett, every day is a blessing, he said.

He does not take anything for granted and sees his mission now to help other inmates like himself who don’t have advocates rallying for them outside prison.

Miller said Corbett is like other men and women coming out of prison after serving long sentences.

“They’re my best residents,” she said. “They’ve learned what it means to really lose a chunk of their life and their freedom, and they don’t want to risk going back.”

She, too, is in favor of commutations and sentence reductions and feels the vetting process by the Board of Parole is thorough.

In the end, she’s sees firsthand what a person can do when given a second chance.

“I’ve found in my own experience that when you wrap around them and give them an opportunity to feel like a person instead of a criminal, you’ll get a person out of them,” she said.

Contact Jen Kocher at jen@cowboystatedaily.com

Jen Kocher can be reached at jen@cowboystatedaily.com.