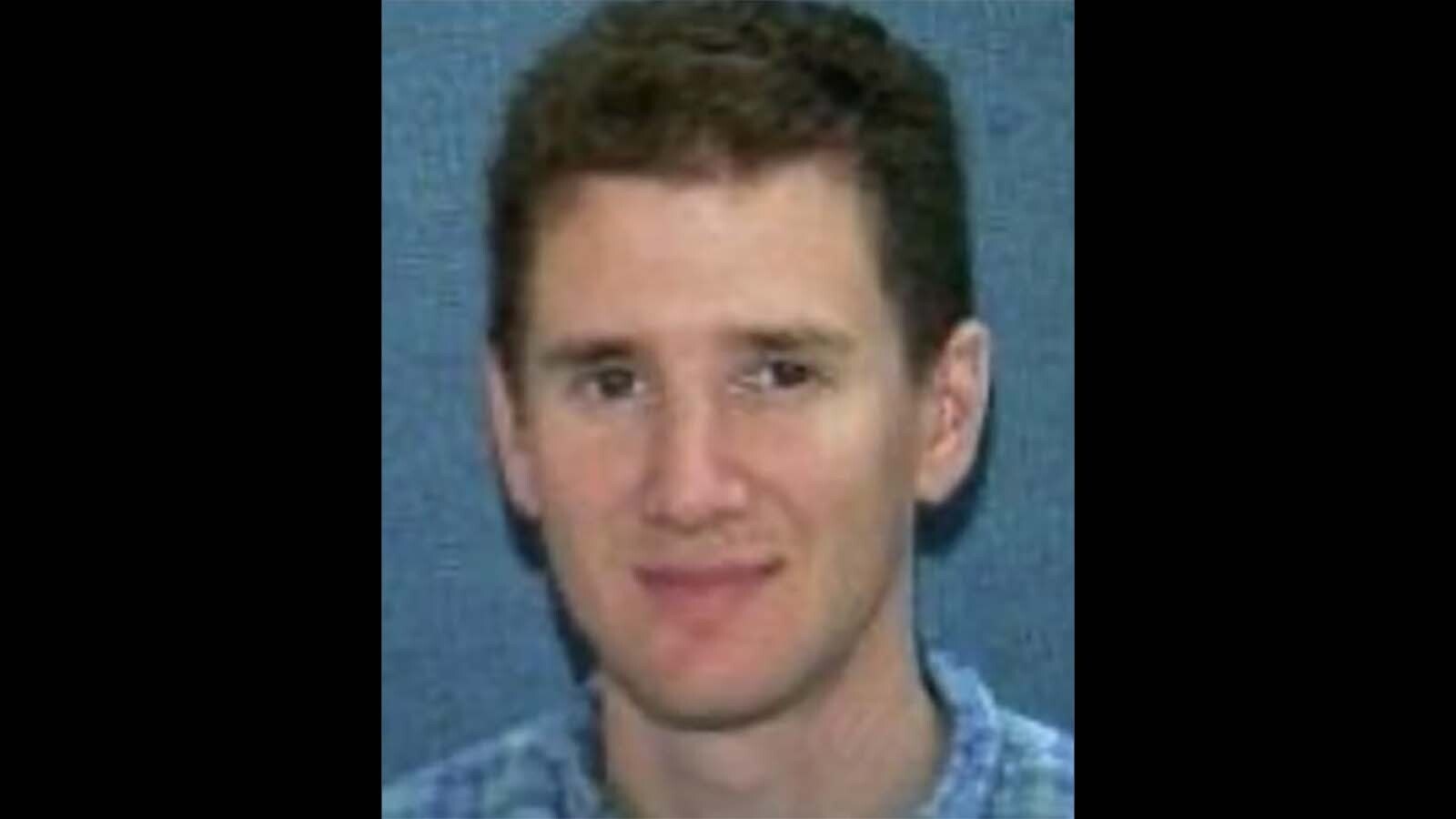

It’s been nearly three decades since a 27-year-old Maryland man disappeared in the Wyoming mountains during a weeklong camping and fishing trip with friends.

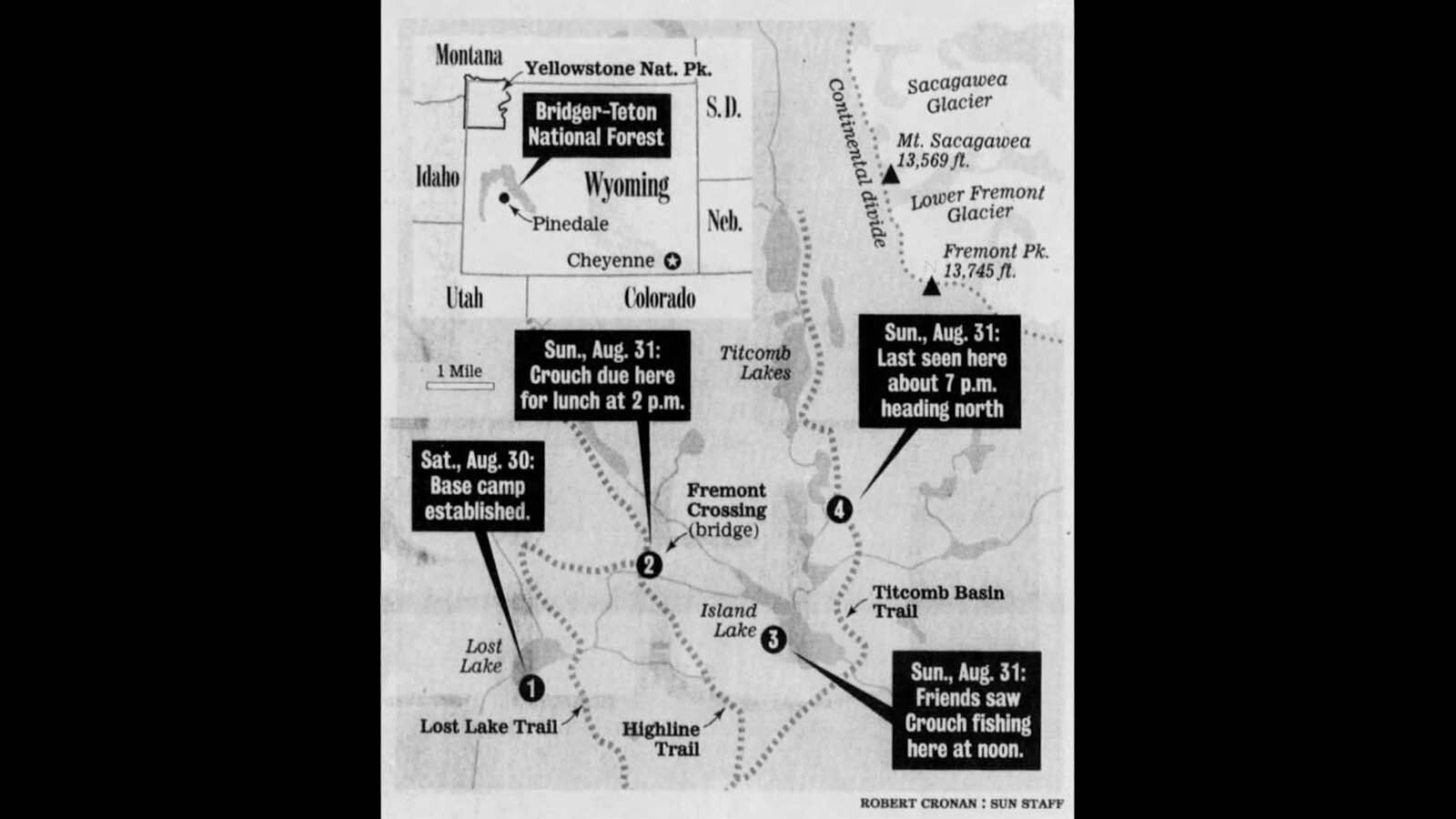

David Crouch had been camping in the Wind River Range in late August 1997 and was last seen on the banks of Island Lake with a fishing rod in hand.

Despite two weeks of thorough searches by the Sublette County Sheriff’s Office and about 50 local search and rescue volunteers who combed miles of rocky and forested terrain with dog teams, horses and helicopters, no trace of Crouch was ever found.

Sublette County Sheriff Hank Ruland was the lead investigator on the search for Crouch, and nearly 30 years later still vividly remembers it to this day.

Ruland, a four-term sheriff who retired in 2005, said Crouch’s disappearance has stuck with him as the mystery lingers. During his tenure, searching for missing hikers and campers in the mountains was not uncommon.

The difference is that typically they are found within a day or two, but not Crouch.

“We tried everything,” Ruland said. “It’s the ones you don’t find that really bother you.”

Need To Explore

Crouch had come from Maryland to Wyoming to fish and camp with three friends.

The group had hired a Pinedale outfitter, Terry Pollard of Bald Mountain Outfitters, to take the group on horseback for a week of camping and fishing in the Wind River Range in western Wyoming.

Pollard did not respond to a request for comment, but he told the Baltimore Sun in 1997 that Crouch couldn’t sit still and was eager to explore the wilderness.

Though he was an avid cyclist, sailor and runner, Crouch reportedly had little experience camping in the wild, an acquaintance told the Baltimore Sun in the same article. As such, he “was charged up for the Wyoming journey,” the acquaintance said.

Given his exuberance, Crouch had a hard time sitting still, despite repeated reminders from both Pollard and his group that they had an entire week to explore.

Repeatedly, they’d warned Crouch that they all needed to stick together out of safety concerns, according to media reports.

“It’s beautiful, pristine country, but it’s also really wild and rough,” Ruland told Cowboy State Daily.

Last Known Sighting

The night before Crouch disappeared, the group had agreed to travel from their campsite a few miles to Island Lake that Sunday, where they planned to fish then meet up for lunch at nearby Fremont Crossing trail junction at 2 p.m., according to the Baltimore Sun.

After making it to the lake, Crouch was last seen fishing on the west side around noon. When that person looked for him again later, Crouch was not there, nor did he turn up for their scheduled lunch.

Initially, the group was not worried. It was a busy Labor Day weekend crowded with hikers and campers, and they figured he would be safe as long as he stuck to the trails. However, hours later when he still failed to appear, they called law enforcement.

Potential Sighting

Despite the relatively high number of people in the area that weekend, only one group of hikers reported seeing someone who matched Crouch’s description, Ruland said.

The group told Ruland they passed a guy in a red and black flannel shirt carrying a fishing pole on a trail several miles to the north and east of where Crouch was last spotted at about 7 p.m.

They’d said “hello” to him, but he passed by without responding.

There’s no way to know if that was actually Crouch, Ruland said, without positive confirmation. If it was him, he had wandered off quite a distance, Ruland said.

Going uphill when lost is consistent for people lost in the woods, according to “Lost Person

Of those lost hikers, 32% to 48% head uphill from their last point of reference in order to get a better view or cell coverage.

Koester also determined that uninjured hikers lost in the wilderness have a 97% survivability rate if located within 24 hours. However, the odds of survival begin to plumet at 96 hours or longer where lost hikers have only a 49% chance of surviving the elements.

Then there’s the weather, which that late August weekend, was not in Crouch’s favor. Not only was it a moonless night with limited visibility, but the temperatures dipped into the 30s the night he disappeared. They further dropped in the proceeding days accompanied by light snowfall, according to news reports.

Crouch was not equipped to survive the cold temperatures or rough terrain.

Dressed only in jeans, a plaid flannel and hiking boots, he didn’t have any of the necessary survival gear, including tent, sleeping bag, water, snacks, compass, matches or anything to help him last a night out in the cold.

He was woefully unprepared, Ruland said.

Family Flies To Wyoming To Help Search

Efforts to reach members of Crouch’s family in Stevensville, Maryland, were unsuccessful, but they have not spoken much about the case over the years. In 1997, the Baltimore Sun said they declined to be interviewed and asked those who had been on the trip with him to do the same.

Crouch was described as an avid runner and cyclist who managed a Stevensville bike store who was married for three years to his high school sweetheart.

Ruland remembers the family flying out as search efforts continued and said they were very polite and helpful and understood the arduousness of the efforts at hand as soon as they saw the difficulty of the terrain and what the searchers were up against.

To date, other than that one potential sighting by the hikers, no trace of Crouch or his fishing pole have been located in the decades since he disappeared.

Best Guesses And Speculation

In the absence of answers, searchers like Ruland were left to speculate what might have happened to Crouch based on his last known location and their own theories and speculation.

If Ruland was a betting man, he would guess that Crouch may have tried to take a short-cut back to their base camp and crossed an inlet above the lake and tripped and fell on the slippery rocks.

The shock of the cold water at the lake at above 9,000 feet would have been jarring to Crouch’s system, potentially causing him to drown with fishing pole in hand.

This theory gained a bit more credence in his mind when a couple years later he and his then-undersheriff helicoptered a couple cadaver dogs into that area, where the dogs alerted on the shore of the lake where Ruland thinks Crouch may have fallen in.

It’s still just a guess, Ruland acknowledged, but the lake was not searched at the time he disappeared.

Better Equipment

Back then, conducting a water search for Crouch would have been difficult given their limited technology at the time and the logistics of getting a search team and boat to the lake had there been credible evidence to suggest he’d fallen in, says John Linn, leader of the underwater team for Tip Top Search and Rescue (TTSAR), a volunteer group that works under the auspices of the Sublette County Sherriff’s Office.

Over the past 30 years, underwater search and rescue technology has improved greatly, and they seldom – if ever – put divers down in high-elevation mountain lakes given the associated risks at high altitudes, he said.

Linn, who has been with the group since 1985, said that today TTSAR uses more advanced technology, including a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) equipped with cameras and a claw as well as a $60,000 side-scan sonar used to locate people, vehicles or boats and other objects under water.

The scanner uses sonar technology that sends out signals that reflect off objects underwater and creates visible shadows and images that the team then analyzes to see if further investigation is needed. If so, the team marks that spot and sends the ROV, which is about the size of a carry-on suitcase, down into the water with live front and back cameras and a grasping claw to latch on to the person or object.

“We have the capability to go 500 feet deep, and it only takes a small generator to run it,” he said. “And you never risk anybody’s life with that robot.”

The TTSAR underwater team is the only one in the state with these particular capabilities and has conducted dozens of missions in Wyoming and surrounding states, Linn said, estimating they have recovered between 15 to 20 victims to date with these advanced tools.

The tricky part of high-mountain lake rescues – both then and now – is getting the equipment to the scene, which requires either being driven in or airlifted by helicopter, including their boats and search crew.

These efforts can be significant, Linn noted, and in Crouch’s case, would also require the permission of the U.S. Forest Service as well as funding to bankroll the extensive operation. They also work solely under the directive of the Sublette County Sheriff’s Office, so likely there would have to be new credible new evidence to get the okay to go in, Linn said.

They've worked on cold cases at the request of DCI and other agencies in the past, he said, but the request needs to come from law enforcement.

“It wouldn't be an active search like we normally do,” Linn said.

In the meantime, Crouch’s disappearance remains a mystery.

Into The Wilderness

Crouch is not the only person to have disappeared in the mountains on Ruland’s watch, though remains the only one yet to be found.

In 1994, George Clock also disappeared in the Wind River Mountain area in one of the more baffling cases of Ruland’s career.

Clock was a 44-year-old robotics engineer from Sacramento, California, who was living in Riverton at the time. He had told friends he was planning to backpack in the Green River Lakes area and possibly scale Gannett Peak, according to reporting by the Casper-Star Tribune.

After his hiking trip, Clock was supposed to meet friends on the East Coast. When he failed to show up, his family reported him missing on Nov. 3.

About a month later, a group of hunters found Clock’s abandoned vehicle hidden in the bushes on Moose Gypsum Road near Green River Lake, about 50 miles north of Pinedale, with its license plates and vehicle identification number stripped off. However, authorities were able to find a second VIN on the vehicle that tied it to Clock.

A few months later, a hiker found the license plates, again hidden in the brush in the same area.

The hidden car and missing plates suggested to Ruland that Clock either was a victim of foul play or had deliberately vanished on his own.

Ruland tends to believe that Clock may have intentionally disappeared and could have been inspired by Christopher McCandless, who like Clock, ditched his car and stripped off the license plates before disappearing into the Alaskan bush in 1992 with the goal of living off the land.

McCandless didn’t last long. His remains were discovered by a moose hunter on an abandoned bus about four months later after he’d starved to death.

Outdoor writer, Jon Krakauer, wrote about McCandless in a January 1993 article for Outside Magazine. He later expanded it into a best-selling book, “Into the Wild,” that was adapted into a movie in 2007.

Given the timing of that first article, Ruland believes there’s a chance that Clock may have read it and also felt inspired to tackle the elements and go off grid.

Despite the similarities in the two man’s stories, Ruland said there’s no way to be certain what his intentions were or if he truly wandered off on his own.

Regardless, given the time of year, Ruland said the odds were stacked against his surviving.

“That's kind of like committing a natural suicide when you go up and challenge the high country in October when a storm is coming,” he said.

Also like McCandless, Clock’s remains were eventually found when a hiker stumbled upon a partial skull north of the Green River trailhead about a year after he disappeared.

His abandoned campsite was also discovered close to where the skull was found, including Clock’s backpack containing keys to his abandoned vehicle, a knit cap, sleeping bag and other assorted outdoor equipment.

It would take authorities two decades to finally positively ID the skull as Clock in 2016, after two prior "inconclusive" lab results, thanks to advanced DNA technology.

Other Missing People

Along with Crouch and Olson, four other people from Sublette County.

This includes Tracy Jensen, who disappeared in February 1999 when he was 23, according to the Wyoming Department of Criminal Investigation’s missing person database. Very little information is available about how he went missing or the details surrounding his case.

Also missing is Vanessa Sue Orren, who was last seen on March 1, 2016, with her boyfriend in a red jeep outside the LaBarge post office.

Decades earlier, 16-year-old Lynn Dianne Olson disappeared while visiting her grandparents’ dude ranch in Green River Lakes on June 28, 1963.

She and her twin brother, Mike, had grown up in the area but had since moved to Salt Lake City with their mother.

Mike, who was also visiting Wyoming with his sister, told authorities that he last saw her walking over a footbridge at the end of one of the lakes.

Search teams scoured the area and dragged the lake where she was last seen.

Then, oddly, her clothing was found about a week later neatly stacked and folded on a rock near the lake in an area that had already been searched, roughly 200 yards from the shore.

This prompted authorities to drag the lake a second time again, with no results, and to bring in divers from Cheyenne to search the water, which Ruland said back then would have been an extraordinary move for law enforcement.

Still, no trace of her was found nor was any evidence recovered. Apart from some reported sightings in southwest Wyoming and Utah over the years that didn’t pan out, there have been no new developments.

Ruland, who at the time was the same age as Olson and her brother, said the mystery has plagued him all these years.

“It was always in the back of my mind,” he said.

He laments the lack of crime scene tools and technologies in the early 1960s but said the sheriff had brought in the FBI to help. Later, when he became sheriff, he dug into the old files and found Olson’s case. Here he discovered a letter to the then-sheriff from former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover promising to send out a couple agents to help.

“They did a pretty good job,” he said. But with no new clues or evidence all these decades later,

Ruland had nothing to work with.

These are the lingering mysteries that stick with the retired sheriff, though he thinks it's never too late.

Anyone with information about any of these missing people is asked to call the Sublette County Sheriff’s Office at 307-367-4378 or DCI at 307-777-7181. Tips can also be submitted anonymously on DCI’s tipline.

Contact Jen Kocher at jen@cowboystatedaily.com

Jen Kocher can be reached at jen@cowboystatedaily.com.