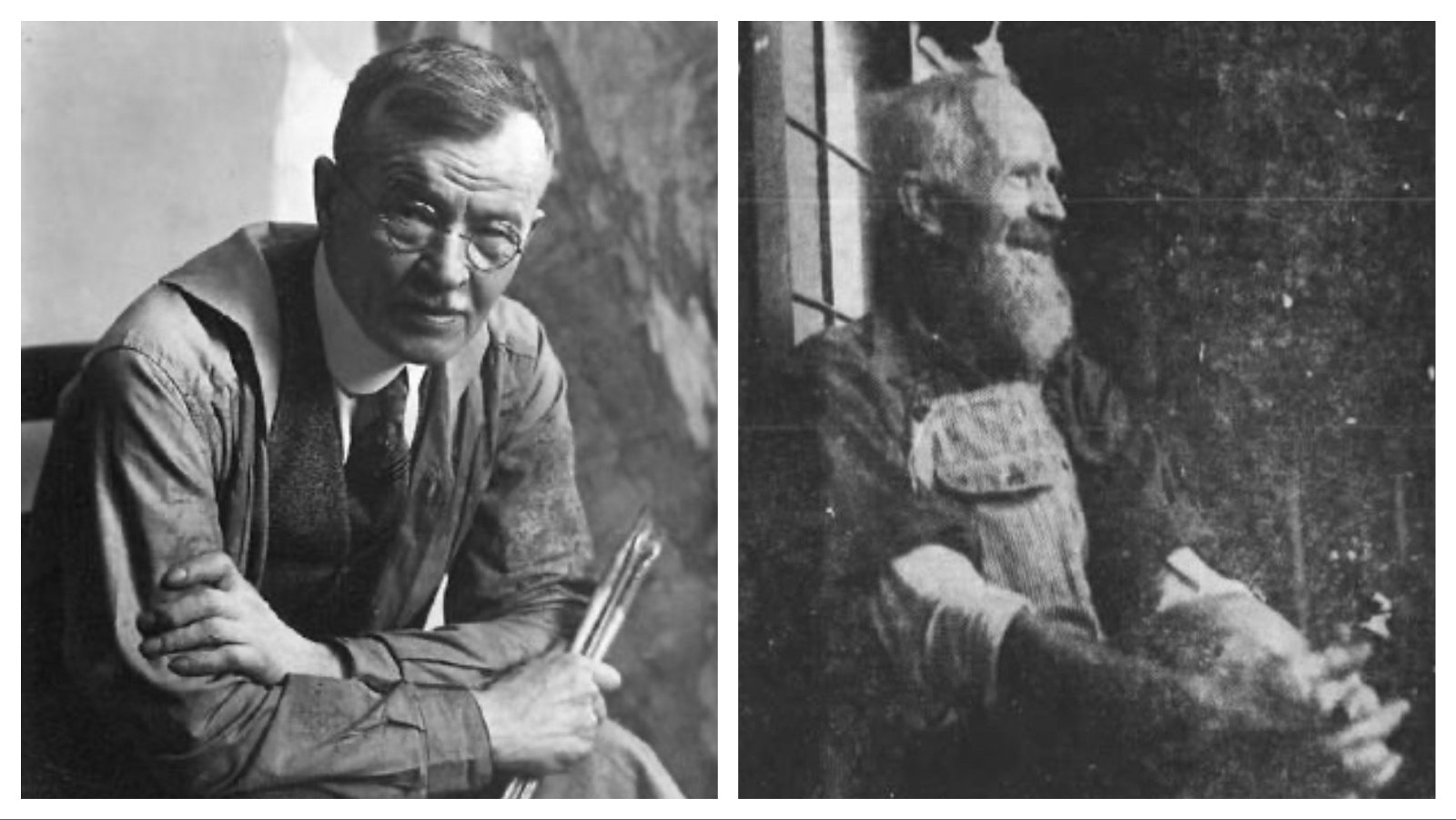

Albert Nelson was Wyoming’s most noted early outdoorsman and wildlife expert. He was a taxidermist, rancher, hunting guide and the state’s first game warden.

From Kelly, Wyoming, and later living in Jackson, Nelson was an expert shot, could survive for weeks in the back country and, in a pinch, set a broken leg.

It was this last skill that led to a famous artist giving him a painting that for many years passed down in the Nelson family after being saved from the 1927 Kelly Flood.

Great-grandson Russell Nelson, 67, now serves as a deputy coroner in Teton County. He said the story of German immigrant and North American wildlife painter Carl Rungius, and his friendship with his great-grandfather, continues to resonate through the family.

In fact, some have called Rungius America’s greatest wildlife artist who still is “widely regarded as the preeminent painter of North American wildlife,” according to the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson.

Immigrants Wind Up In Wyoming

The story of Rungius, who started his wildlife art career in Wyoming, is “kind of one of those known things” in Neslson’s family, he said.

Rungius came to America in 1894 from Germany at the invitation of a relative to hunt moose in Maine.

In 1895, he made a trip to Wyoming before going back overseas. In 1896, he immigrated to the U.S.

Nelson said he believes it was in the late 1890s or early 1900s when the painter and his great-grandfather became friends.

Albert Nelson, born in October 1861, had immigrated from Sweden after doing a couple of volunteer stints in the Swedish military and then when the military decided they were going to draft him, decided to get on a boat to America.

“When he was a child, he had read James Fenimore Cooper and wanted to go to the American West, sort of see that big open country which they apparently didn’t have in Sweden,” Russell Nelson said.

Albert arrived in the U.S. in 1883, spent time in Nebraska working the hay fields, then headed to Wyoming where he worked as a cowboy on ranches south of Rock Springs.

At some point, he moved into what is now Sublette County and built a cabin on the Green River before migrating to the Kelly area and homesteading the Savage Ranch.

He married Sarah Allen in 1900, began having children and served for three years starting in 1899 as the state’s first game warden.

Bad Break

Russell Nelson said his understanding of how his great-grandfather was gifted a Rungius painting was that they were both in what is now Sublette County riding and looking for train robbers. They may have believed the robbers were moving north from the Union Pacific line in the southern part of the state.

Rungius’ horse spooked and threw him, breaking his leg.

“So then, with a broken leg, they may have splinted it up, he manages to ride from somewhere up near the Green River … into the Jackson area and found a physician to set it,” Russell Nelson said. “The story is that the doctor was drunk and didn’t do a very good job of setting it, so they probably at that point in time had gone back to the ranch in Kelly.”

When Rungius realized the doctor failed to set the leg properly, he asked Albert Nelson, who knew about bones and joints as a taxidermist, if he thought he could handle the job of resetting it.

His friend told him he thought he could.

Russell Nelson said his great-grandfather then removed the cast, reset the artist’s leg and put traction on it.

“I guess they ground up the plaster into powder, so he had plaster of Paris and redid all of that, and reset it and it worked a whole lot better,” he said. “And Rungius was pretty grateful for that and that is why they sent him the painting.”

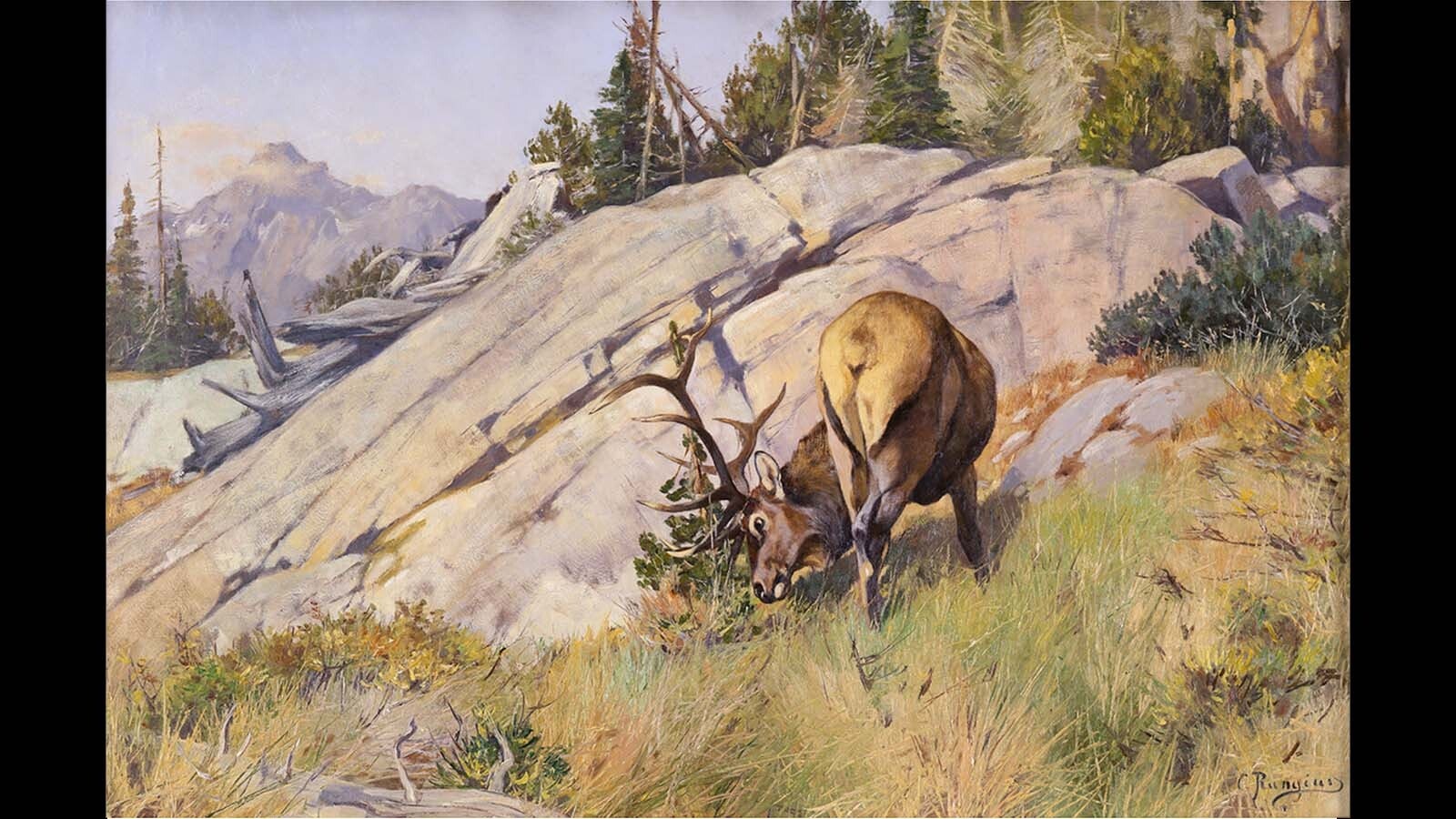

The painting known as “Last of the Velvet” arrived at the Kelly post office as a rolled-up piece of mail and sat there for a year or two, the great-grandson said.

The postmaster then asked his great-grandfather if he wanted it. If not, it was going to get tossed.

A Painting

When Albert Nelson opened it and unrolled it, he found the painting.

Since the family was still at the ranch homestead and wall space was limited, it never was displayed there.

It may have been on the wall after the family sold the ranch sometime in the second decade of the 1900s and moved into Kelly where Albert Nelson had a home for the growing family and his taxidermy shop.

Albert’s wife died in 1913, leaving him with seven children to care for. But Russell Nelson said whether the painting was displayed on the wall of the home or not is not clear.

During the 1927 Kelly Flood that wiped out the entire town, the Nelson home was in the path of the waters as residents scrambled to evacuate.

Albert, then 65, was looking around the home deciding on what to save as the waters rose. Russell Nelson said the family story is that two of his sons picked him up under his armpits and carried him out of the house.

“My great aunt Anna, who was 19 at the time, just looked around, saw the painting and grabbed it and a couple of taxidermy items, I think they were bookends,” Russell Nelson said. “And made it out the door before the waters came.”

Following the flood, the family moved to into a home Jackson. There, the painting did go on the wall for subsequent generations.

“It hung on the wall for quite some time, and it passed down and it wound up in my second or third cousin’s possession at her house,” Russell Nelson said. “And for whatever reason, she needed the money at some point and sold it.”

He said it was sold sometime in the 1960s or early 1970s.

Before it was sold, the family had a photographer take high quality photos of the art and prints were made. Russell Nelson said he and other members of his family have those prints.

Arizona Owner

Jackson’s National Museum of Wildlife Art’s Adam Harris, director of its Carl Rungius Gallery, has tracked the painting to an owner in Arizona who bought it from an art dealer.

He visited the owner and examined the 22-by-34-inch oil on canvas painting.

“The painting itself is a good early work by Rungius, an example you don’t see very often of the elk rubbing the last of its velvet off of his antlers,” Harris said. “Rungius typically wasn’t out in Wyoming quite that early that he would have seen that.

“He would have come out here later in the season normally, so it’s kind of cool for that reason.”

Harris said the location of the painting was likely somewhere between Jackson Hole and the Green River Lakes.

Painting ‘Conserved’

Having been rolled up at the post office for a couple of years, and then rolled up at the family ranch homestead before it was displayed for decades, the painting had to have shown it years.

Harris said when he saw it in Arizona it was in great shape.

“It had been to a conservation studio, so it has been conserved,” he said. “It may not have been in great shape after what it endured living through all those different experiences. Then again, sometimes these things are pretty hardy, and you’d be surprised at what they can survive.”

Works of Rungius can be found online for anywhere from a few thousand dollars to $250,000. Harris declined to put a value on “Last of the Velvet,” but said the artist’s paintings in the middle of his career are the most valued.

Born just three months after his great-grandfather died in March 1957, Russell Nelson said that in addition to the story about the painting and Rungius’ leg, there are several other tales about his great-grandfather, who is in the Wyoming Outdoor Hall of Fame.

Russell Nelson’s father, Albert “Boots” Nelson, told him the story about the family patriarch’s last hunt in the mountains with his 1903 Mannlicher Schoenauer 6.5x54mm rifle and his expertise as a marksman at long distance.

“There were a herd of goats that were passing in front of them,” Russell Nelson said. “He goes, ‘There’s a kid I dropped behind that sand dune over there,’” he said. “(They) went over and sure enough there it was. … He was evidently pretty amazing.”

Contact Dale Killingbeck at dale@cowboystatedaily.com

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.