LARAMIE — Everett Spackman was 16 when he bought his first car — a 1926 Model T Ford he paid $6 for.

It was used, but then hardly a classic.

Spackman’s coming-of-age achievement of getting his own car and instant mobility happened in 1941.

“It was once a fire truck that I paid $6 for,” he said. “There was no seat where one was expected to sit. I sat on the gas tank.”

And like many rural kids who grew up in farm country, Spackman was hardly a novice behind the wheel. He’d been driving for four years by the time he was “legal” to drive.

“I had two Model Ts,” recalled Spackman from his home in Laramie, where he celebrated his 100th birthday in March.

He can’t fully recall which, but with one of the Model T Fords, he learned the hard way that even those early cars won’t run on kerosene. He’d heard somewhere they would, “but it didn’t very well, I found out.”

During his century on the planet, Spackman remembers living through the Great Depression, severe rationing during World War II, getting his family’s first television and watching Walter Cronkite with millions of other Americans as Neil Armstrong took humanity’s first steps on the moon July 20, 1969.

Spackman now lives life a little slower, but is still remarkably spry for a man who’s seen the terms of 17 presidents (18 if you count Trump as Nos. 45 and 47) and grew up with outhouses and party-line telephones.

There’s no secret, he said, although in the weeks since hitting triple digits people seem to ask that a lot.

“It’s just not having died yet,” he said, adding he doesn’t feel any different than he did at 99. “No, not really. Feels the same.”

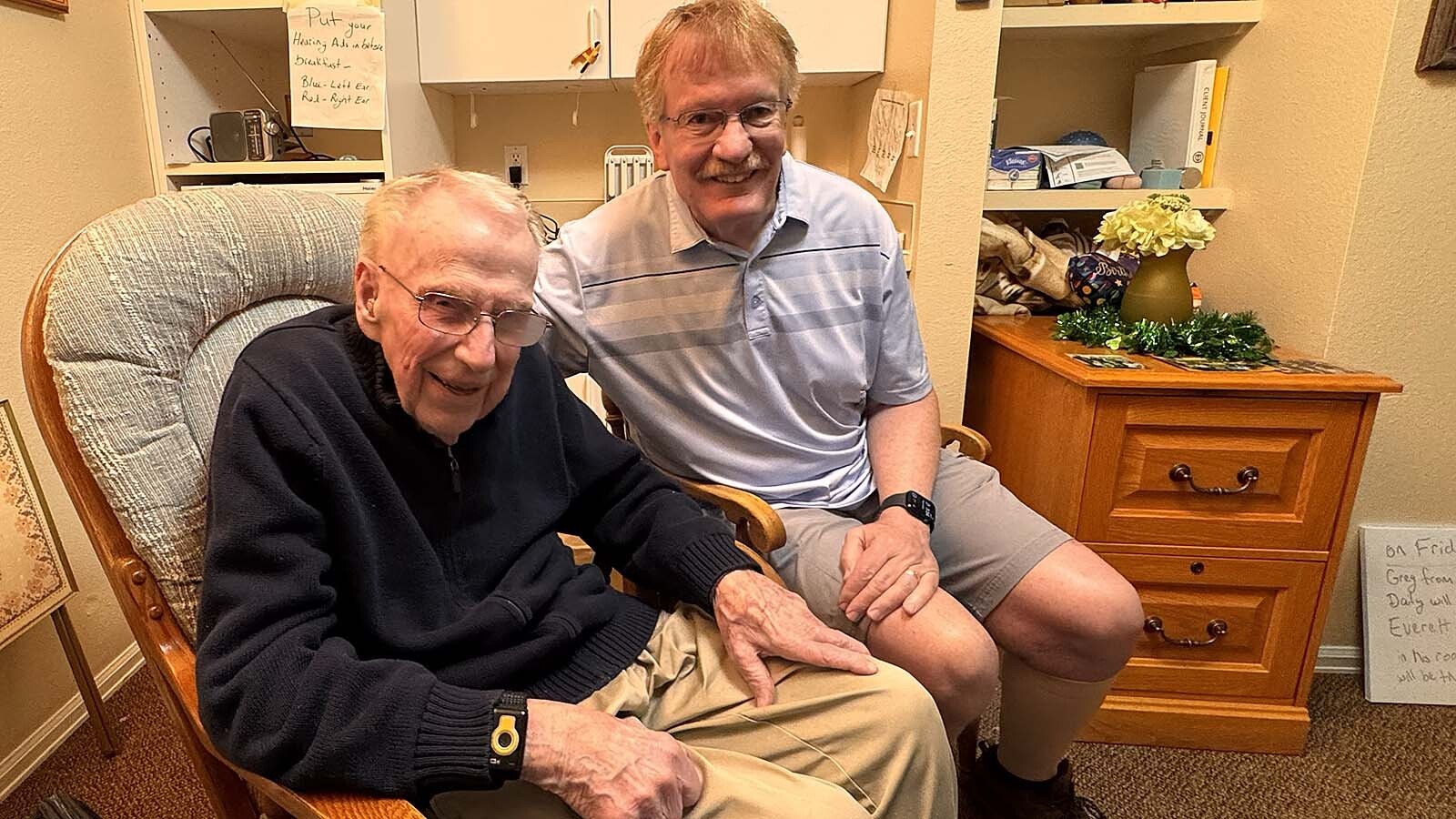

Cowboy State Daily recently sat down with Everett and his son Lowell to talk about a remarkable life that’s still going strong.

Along the way, he was married for nearly 70 years, raised four kids in Wyoming and held a 19-year appointment from Gov. Clifford Rogers.

This story is a product of that interview and those done by Lowell to chronicle his father’s life and shared with Cowboy State Daily.

Dad, The Veterinarian

Although Spackman has been in Wyoming longer than most native Wyomingites have been alive, he wasn’t born in the Cowboy State.

He’s the fourth of five children born to Edmund Paul and Garnett Irene Spackman on March 5, 1925, on a farm west of Fullerton, Nebraska.

Some of his earliest memories are intertwined with his father being the area’s veterinarian, a very important and critical job in the heart of farmland.

Aside for being on call 24/7 for whenever farmers and ranchers had sick animals, Everett recalls how his dad always had a car.

“Dad had to have a car to get around,” he said. “So, they had a Model T Ford soft-top.”

He only remembers his mother driving the car once.

“I think she may have backed into something in the yard, and I don’t believe she tried driving again,” he said.

Like most fathers in Nebraska — and later Wyoming when Everett had his own kids — he recalls learning how to shoot. People were taught young how to shoot and be safe doing it, and rarely had any troubles, he said.

He also said he and his four siblings learned early that “when my dad said no, he meant no,” Everett said.

Perhaps some of the most moving memories of his father are from the Great Depression, which hit their community hard.

Farmers often called him to come treat sick and dying animals even though they couldn’t afford to pay. They had no choice, Everett said. For them, the survival their cows, sheep, pigs and even chickens meant life or death.

“Many times dad would make a call and treat the animal and would not be paid,” he said. “And if he got a call about a sick animal, that call came first above any family plans.”

The family “was able to survive somehow,” Lowell added. “But he wasn’t getting paid much. But he was probably doing a lot better than some other people at that time.”

Growing Up Small Town

Everett smiles a lot talking about his early years growing up in Nebraska. To say it was a simpler time isn’t just cliché or hyperbole.

Families had outhouses as there were few houses with indoor plumbing, and Everett and his siblings walked nearly a mile to school every day. If the weather was good, they’d walk home and back for lunch.

There was no hot water, it was heated in a boiler by the cook stove, and his mother made her own lye soap to clean laundry with. She did that with the lard rendered from a pig that had been butchered.

Even on the first day of kindergarten, Everett was expected to walk to and from school.

On the way home, “I recall walking down the middle of a residential street, crying,” he said. “A man heard me, came out and tied my shoe. When he found out my name, he took me home.”

The boy children — there were three — were expected to do their chores. He laughed when asked if he think kids today would be up to doing the same daily chores he and his siblings were given.

“We had a milk cow so long as one of us boys was around to do the milking,” Everett said. “Sometimes, the gate to the cow shed would have been left open.”

That added an extra chore early in the morning, often before the sun was up — go catch the cow and bring her back.

“We were living in hard times,” he added. “One Christmas, I got a pair of house slippers, a sheath knife and a hand ax with a sheath. We never had a Christmas tree until my sister, Helen, bought one on her 10 cents an hour salary at the 5 and 10 Store.”

Coming Of Age

As he grew older, Everett said that meant more freedom and exploring.

There were no cellphones or touchtone phones when he was growing up. Every farmhouse had a telephone on the wall you had to crank to use.

There also was no call waiting, messaging or even direct lines. All the telephones were on “party lines,” he said.

“When we wanted to make a call, we raised the receiver and an operator would say, ‘Number please,’” Everett said. “You would tell her the number … then she would complete the call.”

There also was a reason and protocol for cranking that handle on the side of the telephone.

“You crank them to give off either short of long rings, and each person on a rural line would have his or her own combination of rings,” he explained. “You were expected to only answer when it was your ring. But whoever was on the line, they could listen in.”

Everett said he and his friends also started early hustling to earn some money.

One job he had was handing out fliers for the local movie house. He also mowed lawns for 25 cents and caddied for golfers at the local course. He’d get $1 to carry bags for 18 holes.

Kids used to hitchhike 23 miles to St. Edwards, Nebraska, to swim, he said. They’d sometimes take the family .22 rifle to shoot rabbits.

“One time when some of the older boys got tired of swimming and it was watermelon season, they would swim upstream and steal melons,” Everett relayed through Lowell. “One time, some of them came back with buckshot in their backs.”

Everett The Military Man

A few years after buying his first Model T for $6, Everett graduated high school with the Class of 1944.

“I reported for induction into the military two days after high school graduation,” he said. “At the time I went in, they were giving you a choice of Army or Navy. I chose the Navy, and my cousin chose the Army the same day.”

He served during World War II through 1946, and said his ability to type likely saved his life.

Sent to Landing Craft School to train how to operate troop carriers like the ones used for beach landings, Everett was about set to deploy. It was a dangerous, and many times fatal, job because those troop transports drew heavy enemy fire.

That’s when someone noticed he could use a typewriter.

“That was a real (skill) back then. Not a lot of people could use a typewriter,” he said.

He was instead reassigned as a Yeoman 3rd Class and sent to San Diego, California, where he spent his whole deployment.

He’d go on to graduate in 1950 as an entomologist from Colorado A&M College — now Colorado State University.

He also made a decision that would pull him into the Korean War as well.

“I had some buddies, some guys, and we decided we would all join up into the Naval Reserves,” Everett said. “They said it was an easy $50 a month.

“Well, everything went as planned until (the United States) entered the Korean War.”

He was called up to active duty and served two more years in the regular Navy. This time, he was assigned to the USS Guadalupe, a tanker that would refuel and re-supply other ships.

Between both wars and the reserves, Everett Spackman served six years, nine months and 28 days.

On To Wyoming

It wasn’t long after the Korean War that Spackman found his way to Wyoming, where he would remain.

By then, he and wife Eunice Erdene Spackman were married, and they celebrated 69 years together. She’s passed away Jan. 25, 2019, but they lived a full life and raised a family along the way.

They met at college in Fort Collins, Lowell said.

“He was ‘batching’ with a buddy in the basement of a house and his future wife was living with her aunt in the main level of the house,” he said.

While caring for animals was his father’s calling, Everett aimed a little lower — literally.

He became one of the nation’s leading entomologists. He was appointed by Governor Rogers as Wyoming State Entomologist in 1954, a post he would hold until 1968.

After that, he began a long career as a Wyoming Extension entomologist at the University of Wyoming, which he did until he retired in 1995.

Insects are fascinating, he said.

Everett also bristles when asked what his favorite bug is.

“They’re not bugs, don’t call them bugs,” he said, firmly. “They’re insects, and insects have six legs.”

That leaves out other creepy-crawlers like spiders and scorpions. While not insects, he likes those just fine, too.

In fact, he probably loved insects a little too much. Lowell remembers there were always containers with insects in them in the refrigerator at home.

“I’m sure (mom) was tired of it, but she made sure they were in the refrigerator and not crawling around the house,” Lowell said.

It did, however, prompt everyone to learn early on to always check what they pulled out of the fridge.

No Secret

Although he can’t work with wood the way he used to — Everett was a talented carpenter, his son said — he likes to keep busy.

He also said keeping physically in shape throughout life has been a blessing as he’s grown older, but the signs of age are there.

He’s a little hard of hearing and can’t be as active as he once was, but Everett is upbeat, happy and smiles a lot. And he’s very proud to wear his Navy hats that proclaim the dates of his service.

For Lowell and his siblings, Everett is dad, and those old stories about using outhouses and paying $6 for a Model T are as entertaining as the first time they’ve heard them.

“They were always there for me,” Lowell said about what stands out most about his parents. “I was a swimmer, and no matter how busy dad was or where in the state he was supposed to go, they always made time to come to my meets.”

Asked for advice on getting to 100, “There is no secret,” Everett said. “I don’t know. People ask, ‘How do you feel?’ I guess I feel pretty good. I’m still very active.”

Lowell said he hopes longevity is in his genes as well, but admits he sometimes has to catch himself getting impatient with his 100-year-old dad.

“What he’s shown me is he does things pretty slow now, and it drives me crazy,” he said. “But then I remember he’s lived 100 years. He can do whatever he wants.”

Greg Johnson can be reached at greg@cowboystatedaily.com.