Cody’s Heart Mountain isn’t the result of one of the largest known landslides in Earth’s history. It’s the result of two of the largest landslides in Earth’s history separated by nearly 50 million years.

There’s a lot that makes Heart Mountain, the iconic peak north of Cody in Park County, unique in the geological context of Wyoming. That’s saying a lot, considering the Cowboy State is one of the world’s most lauded geological wonderlands.

It’s a story of a block of rock the size of Rhode Island moving at 700 mph, an eruption of the Yellowstone supervolcano, and two separate but equally cataclysmic events in Earth’s geologic history.

Thomas Bown and Albert Warner are the authors of “The Heart Mountain Detachment: A Critical Reappraisal,” which was published in February.

It’s a comprehensive look at the geology of Heart Mountain that presents a new interpretation of how it came to be, revealed by the complex geological landscape and evidence scattered across the northwest corner of Wyoming.

Their conclusion is that it took less than 30 minutes to make Heart Mountain, but that 30 minutes was stretched across 47 million years.

“We believe that Heart Mountain constitutes the world’s largest known landslide, but there are two different structures from two different events,” Bown told Cowboy State Daily. “They’re contiguous but separate. It’s complicated.”

The World’s Largest Landslide

Heart Mountain is a geological anomaly for several reasons. For one, the rock at the top of its iconic peaks is significantly older than the rock at its base, violating the geological law of superposition.

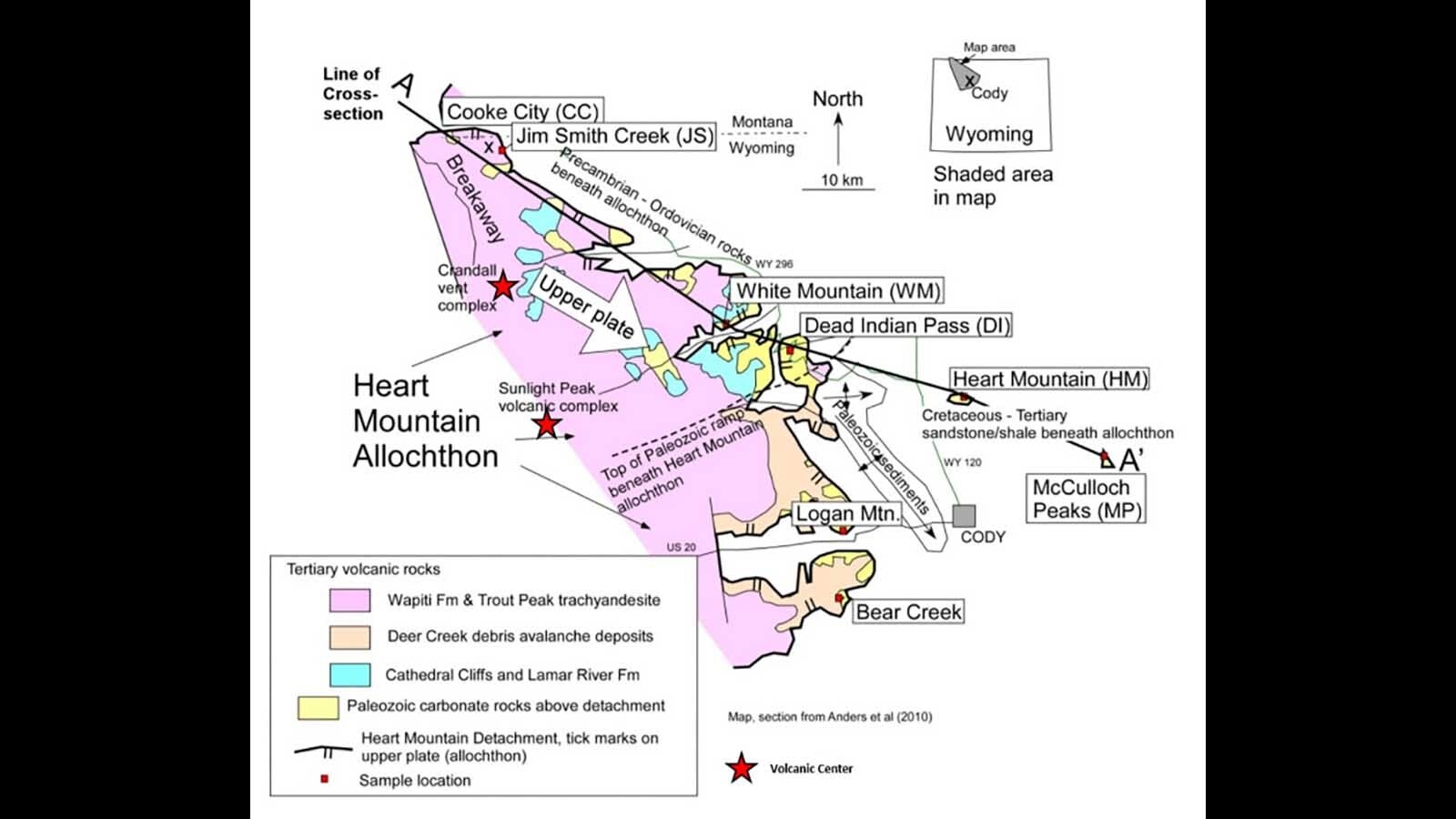

Also, the mountain belongs nearly 50 miles northwest of Cooke City, Montana. All the evidence indicates that the geology of Heart Mountain is a massive block of Bighorn Dolomite that was initially attached to the rest of the formation exposed along the Wyoming-Montana state line at the northern extent of the Absaroka Range.

So, how did it get from Cooke City to Cody?

“The debris of Heart Mountain constitutes the world’s largest landslide,” Bown said. “A block of Bighorn Dolomite that was the size of the state of Rhode Island rafted about 40 miles from its source around 49 million years ago.”

Calling this event a “landslide” understates its enormity. The state-sized slab of Paleozoic sedimentary rock moved at 100 meters a second, covering over 40 miles in less than 30 minutes at speeds over 700 mph, leaving behind a field of “mountains” and other debris across an expanse over 40 miles long and 15 miles wide.

“We believe it was caused by a massive subduction zone earthquake, 9.0 or higher,” Warner said. “An earthquake of that intensity would have lasted from 4 to up to 10 minutes.”

An earthquake of that length and intensity would have reduced the surface friction to the point where it barely existed. Bown compared the incredible geological phenomenon to an electric tabletop football game.

“The blocks skidded across the landscape like the football men on the field,” he said. “Paleomagnetic studies have shown that the massive block broke, and those individual blocks rotated as they went. It was like a vibrating conveyor belt.”

The “Heart Mountain Detachment” came to rest at the present-day location of Pat O’Hara Mountain, the prominent peak directly west of Heart Mountain, where 500-million-year-old limestone and dolomite sit on top of 55-million-year-old mudstone and shale. It took less than 30 minutes for the blocks to cover a distance of nearly 40 miles.

It’s hard to visualize the scale of this event, but the evidence of it is spread throughout northwest Wyoming. Many of the “mountains” visible from the pinnacle of Dead Indian Pass are pieces of the Rhode Island-sized block of Bighorn Dolomite that broke off and settled during the landslide.

“One of the more recognizable features along the Chief Joseph Highway is the Cathedral Cliffs,” Warner said. “That’s one of the largest breakaway blocks from this landslide. Republic Mountain right outside Cooke City is another one of these blocks.”

But, according to Bown and Warner, that event didn’t create modern-day Heart Mountain. It stopped just short of reaching that spot and needed another unprecedented geological event to finish the job.

Another One?

This is where the story of the Heart Mountain Detachment usually ends – a single event that occurred 49 million years ago. Bown and Warner believe there’s more to this story.

Their new book focuses on the bigger picture of the world’s largest landslide. They believe the McCullough Peaks, south of Cody, indicate another cataclysmic event that was associated with but not attached to what’s been understood as the Heart Mountain Detachment Fault.

“McCullough Peaks was believed to be part of the Heart Mountain Detachment Fault, but that’s all early Eocene in age,” Bown said. “The deposits around McCullough Peaks are all early Pleistocene in age. They both have older rocks sitting on younger rocks, and they're contiguous, but they sit on surfaces of very different ages.”

After studying the existing research and geology of the region, Bown and Warner concluded that there’s a distinct difference between the two deposits. That indicates that another event must have occurred to create the McCullough Peaks.

“It's completely different and separate from what most people consider the Heart Mountain detachment fault,” Bown said. “The mountain itself is not part of the fault. There’s one structure beginning near the eastern edge of Yellowstone National Park and going all the way east of McCullough Peaks. Now we believe that's the result of two structures, separated in time by 47 million years.”

In their book, Bown and Warner present their evidence for two different events: the Shoshone/Sunlight/Abiathar Detachment Fault, which created Heart Mountain 47 million years ago, and the Heart Mountain/McCullough Peaks Sturzstrom, a rock avalanche that only occurred around 2 million years ago.

Warner said these were “contiguous but separate events” with similar outcomes. Both involved enormous landslides that led to the creation of mountain ranges, but the 47-million-year difference makes all the difference.

“We believe that an earthquake of great intensity generated the older movement in the Eocene,” he said. “The younger movement, the one that created the actual Heart Mountain and McCullough Peaks deposits, happened during an immense volcanic eruption accompanied by earthquakes that took place about 2 million years ago in the Pleistocene.”

What was the source of “the younger movement?” Look no further than the supervolcano next door.

The Caldera Culprit

The source of the 49-million-year-old landslide earthquake is still disputed. It was possibly caused by “frictional heating” associated with plate tectonics, as magma deep under the Earth’s surface heated and lifted the dolomite, causing the Rhode Island-sized detachment.

Meanwhile, Bown and Warner think the source of the 2-million-year-old landslide earthquake can be directly traced to the volcanic hotspot that moved into northwest Wyoming during the 47-million-year gap between the geologic events.

“That was the result of silicic eruptions in Yellowstone National Park that resulted in the collapse of the caldera,” Bown said. “It was probably the most violent volcanism in the history of that range.”

Around 2.1 million years ago, the Yellowstone caldera underwent one of the largest eruptions in its history. It occurred right when the volcanic hotspot burned its way into the northwest corner of Yellowstone National Park.

Over 590 cubic miles of ash were ejected from the caldera, creating a layer of volcanic ash known as the Huckleberry Ridge ash bed. It stretches as far south as the Mexican border, as far north as the Canadian border, and across the Western U.S. from southern California to the Mississippi River.

An eruption of that intensity would have generated devastating earthquakes in its vicinity. A modern-day analogy would be the landslides and other events prompted by the eruption of Mount St. Helens in 1980, only on a much larger scale.

This incredible event is what Bown and Warner believe created Heart Mountain as it exists today.

Their research concluded that the original detachment ended in the Absaroka Mountains. The massive blocks that became Heart Mountain and McCullough Peaks didn’t descend to their current locations until the Yellowstone eruption 2.1 million years ago.

“The easternmost remnants of the Shoshone/Sunlight/Abiathar Detachment Fault came to rest in the area of the Natural Corral, north of Pat O’Hara Mountain,” Bown said. “They piled up and sat there for 47 million years, and then an immense volcanic eruption caused this mass to break away and sweep down the Shoshone River as a landslide.”

That would mean that Heart Mountain, which is composed of 500-million-year-old rock sitting on 50-million-year-old rock, is a massive breakaway of a much more massive block from a 49-million-year-old landslide but only reached its current location around 2 million years ago.

Two From One

If all these intricacies seem complex and confusing, welcome to the complexity of geology. The “controversial” takeaway from Bown and Warner’s research is that Heart Mountain wasn’t formed as part of the Heart Mountain Detachment Fault.

“The debris from the Heart Mountain/McCullough Peaks Sturzstrom is very different from the Shoshone/Sunlight/Abiathar Detachment Fault, which is an almost completely unique structure,” Bown said. “Both were earthquake-generated but have very different internal structures and mechanisms.”

Their research indicates that Heart Mountain wasn’t the result of a single event, but two separate events of similar scale. Bown and Warner recognize that their interpretation will shake up the accepted explanation for the geologic events that led to modern-day Heart Mountain.

“There's always more that you can study, so we can learn more about what happened,” Bown said. “With additional study, you can learn more about the speed, internal mechanics, and movement of these landslides, which isn't completely known today.”

Landslides and sturzstroms are relatively common in the present day and geological history, but not on the scale of what occurred in northwest Wyoming twice in 50 million years. Fortunately, many geologic processes look and behave similarly, even if their scales are immensely different.

Warner is examining possible analogies for the events in the Philippines. Insight into similar events from the past and any possible events in the future could reveal more information on what happened in northwest Wyoming 49 million years ago, and again 2 million years ago.

“The Philippine Area is an incredibly active tectonic region, so earthquakes there are very, very common,” he said. “There is a study of a particular block of Miocene rock that broke away and created a strip surface very similar to the surface of tectonic denudation originally described around Heart Mountain. A very similar situation, but on a much smaller scale.”

Natural Monuments

A lot has changed in the 50 million years since the initial detachment that led to the formation of the modern-day landscape in northwest Wyoming. Evidence that could reveal more about these incredible events has been lost to the inevitable passage of time.

“Part of the problem of studying the Shoshone/Sunlight/Abiathar Detachment Fault is that it immediately preceded a period of enormous deposition,” Bown said. “It happened right before the beginning of volcanicity and tremendous buildup of volcaniclastic sediments in the Absaroka Range, so much of that evidence has been buried.”

Meanwhile, the evidence of the Heart Mountain/McCullough Peaks Sturzstrom is eroding and readily available for scientific scrutiny. Bown and Warner hope their book will increase interest in the area and challenge more geologists to scrutinize their work and the geology that led them to their conclusions.

The geologists also hope that more people become aware of these incredibly dramatic stories of unprecedented catastrophes and mountain-building that created the striking landscapes in and around Cody, Cooke City, and Yellowstone National Park.

When someone looks upon the iconic peak of Heart Mountain, they aren’t looking at a traditional mountain. They’re glimpsing the result of the largest known landslides in Earth’s history — a massive mountain that’s just a small part of a much grander story scattered across the region.

“One of the things Tom and I have discussed is that there’s nothing about the geology posted at the summit of Dead Indian Pass,” Warner said. “We would love to see some geological recognition at that particular site, because there are a lot of natural monuments to these events. When you recognize what occurred there, it’s truly spectacular.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.