Editor’s note: This story deals with suicide, mental illness and subjects some may find disturbing. Read at your discretion.

Joran Cochran was a sociable kid, sometimes too sociable for his own good.

His middle school teachers moved him around like a chess piece to stop him from talking to friends during class. But it hardly fixed the issue, because Cochran made friends with everyone they put him next to.

“I remember one of his teachers called me to say she had to move him three times in the same class,” said his mother, Kari Cochran, born and raised in Rock Springs. “He would make friends in any situation that he was in. He was so social and he just really liked people.”

That outsized personality paired well with his bouncy mop of brown curly hair and sky-blue eyes. Though it stood in contrast to his figure: when he entered Rock Springs High School standing 4-foot-11 and weighing 95 pounds, making him among the smallest students in his class.

What he lacked in stature he made up for with a competitive nature, especially in contact sports like wrestling.

As his teammates were cutting weight for advantage, he was bulking up simply to meet the minimum weight, which paid off when he won the status of a freshman letterman.

Even so, his small size was a source of insecurity as well as a point of belittlement from his peers and coaches, his mother said.

Kari Cochran said her son was the victim of pervasive verbal and physical disparagement that compounded his mental health and set him down a path to self-harm. That path reached its end point Feb. 3, 2023, the day 18-year-old Joran took his own life.

His experience offers a lens into some of the biggest factors driving Wyoming’s intractably high suicide rates, which have only grown worse since Joran’s death, making the lessons of Cochran’s personal story as urgent as ever.

His young adult years were punctuated by a series of demeaning incidents, spiraling mental health and failed interventions.

In hindsight, it paints a picture of a culture with broken guardrails for at-risk youth, beginning at the public high school.

Are Schools Failing At-Risk Kids?

As a freshman, Cochran sprung into Rock Springs High School with his hallmark social buoyancy.

Four years later, he limped out with the shrunken spirit of a trauma-altered soldier returning from a foreign war, beleaguered by years of micro aggressions and cruel acts of hostility.

The trouble began in his first year.

During a nighttime bus ride home from a winter wrestling meet, he was pinned down by a larger student and sexually assaulted; the student attempted to put a finger in Joran’s anus.

He screamed for help and was released once the coach made his way to the back of the bus. But the nature of the assault did not surface until later.

In a state of hysteria that night, Joran divulged to his mother what happened. The next day, she started petitioning the school district to pursue a sexual assault charge under Title IX. Following an internal investigation, the district declined, explaining its reasoning in this way:

“... the incident with the respondent's finger occurred outside the clothing, did not penetrate the anal opening and is an isolated incident. Therefore, this incident does not meet the criteria of Title IX as it is not so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive that it effectively denies equal access to the District's education program or activity,” wrote Sweetwater County School District Human Resource Generalist Teresa Wells in a text message to Cochran that she shared with Cowboy State Daily.

More Torment

The incident and its lack of redress left Joran feeling distrustful, unsafe and alienated from his wrestling community. Those feelings got worse from there.

It wasn’t long after that Joran was choked unconscious and dropped to the floor by a fellow student just feet from the principal's office in the school’s crowded main hallway before first period, an incident that was captured by surveillance cameras.

The school’s vice principal intervened when he saw Joran on the floor. He was cleared by the school nurse only to be diagnosed with a concussion by the family’s primary care doctor later that day.

This time, his aggressor was penalized with suspension, but the torment was far from over.

Joran would soon find himself deeply humiliated after email correspondence between his woodshop teacher, Harvey Dalton, and wrestling coach, Brad Profaizer, was leaked to the student body.

The email belittled Joran by name and suggested the wrestling team was better off for the fact that he hadn’t qualified for the state tournament. It was left open on the teacher's desktop computer, where it was secretly read by a student who then took a photograph and shared it among peers.

Warning Signs

Each additional embarrassment and betrayal exacerbated his mental health, fueling a feedback loop as he fell into worse habits and behavior as a result.

His junior year, Joran was written up for poor behavior in class that resulted in a stiff reprimanded from his wrestling coach. This was the beginning of the end, said Kari Cochran, because it ultimately drove him from the thing he valued most.

“Wrestling had been what he identified with, it was who he was,” she said. “It made him feel strong and big and part of something. When those coaches ringed him at practice to the point where he burst into tears, calling me just losing his mind, that was the start of the complete downward spiral because that’s when he quit wrestling.”

Through the eyes of his mother, peers and authority figures put a target on Joran’s back. Over time, he internalized that target and eventually he began taking aim at himself.

By his junior year, he was regularly vocalizing a desire to end his life, which showed up alongside other problematic behaviors, like drinking underage.

He was cited for underage drinking and court ordered to attend an evaluation group. The shifting cast of program supervisors and his inability to connect with the groups' far older members made him feel even more alone in his struggle, his mother said.

It motivated her to run for a position on the local school board, which she won in 2022 and began advocating for extra mental health support for students. But the student she cared about most was only proving harder to reach.

In that same year, Joran was found unconscious from intoxication on a residential lawn.

From there he was taken to Sweetwater County Memorial Hospital, where Kari Cochran hoped to get a mental health evaluation that would start the process of treatment. Neither Joran nor doctors seemed interested in the idea, according to her.

“He was screaming that he wanted to die, and it took six people to hold him down,” she said. “They gave him some [medications]. I was requesting that they put him in a behavioral health program, but nothing. No one gave us any options for that.”

She recalls a day in 2022 when Joran was expressing suicidal thoughts. Feeling helpless, she got him in the car and headed again toward Sweetwater Memorial Hospital, begging him to cooperate and look into transferring to a treatment program in Cheyenne.

“When I told him we’re going to the hospital, he immediately said, ‘No, let me out!’ And then he jumped out of the car,” she said.

“One of the biggest things for Joran was that he had so much broken trust. He didn't really trust that people, especially people with authority, were there to help him,” she added. “There was always someone there to blame him or to shame him, or insult or critique him. But not to support him. He had no trust in anyone in Sweetwater County.”

Joran's Last Day

On Feb. 2, 2023, Kari, Joran and his father Mike were together in the kitchen at 8:15 a.m., where they started discussing text messages Joran sent his mother saying he wanted to “crawl into a hole and die.”

The moment she raised the prospect of treatment programs, Joran erupted. He began screaming and yelling that he wanted to kill himself. She called police while following him from room to room attempting to calm him down.

“I was trying to talk to him about getting help, trying to get him to stay home and stay in the house and wait for the police to get there. I was just praying that they would get there and that they would keep him there,” she said.

He burst out the front door at 8:45 a.m. before the police arrived.

At the end of a long day of searching for her son, Cochran that evening noticed the family dog, Apollo, staring intently out the front window, his eyes fixed on Joran’s 1985 Toyota 4Runner. The car was not drivable and was parked on the side of the home awaiting repairs.

Through the dark tinted windows, she vaguely discerned the shape of a figure in the driver’s seat.

She grabbed her husband and they rushed outside. The driver’s side window was spiderwebbed with broken glass. Joran was slumped in the front seat with a gunshot wound to his head, deceased.

The gun belonged to his father.

Final Record

The family is now mired in a battle with the school district over Joran’s records, which are being withheld under the auspices of Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. Because his parents were not designated as Joran’s next of kin, the district says, it cannot share his records, she said.

The Cochrans contest this logic and believe the records are being unduly withheld over fears of legal liability.

What’s Being Done?

Joran Cochran’s story represents a vortex for so many of the individual and social problems that lead to suicide. Bullying, unhealthy media diets, easy access to guns along with insufficient and ineffective institutional support programs for mental health.

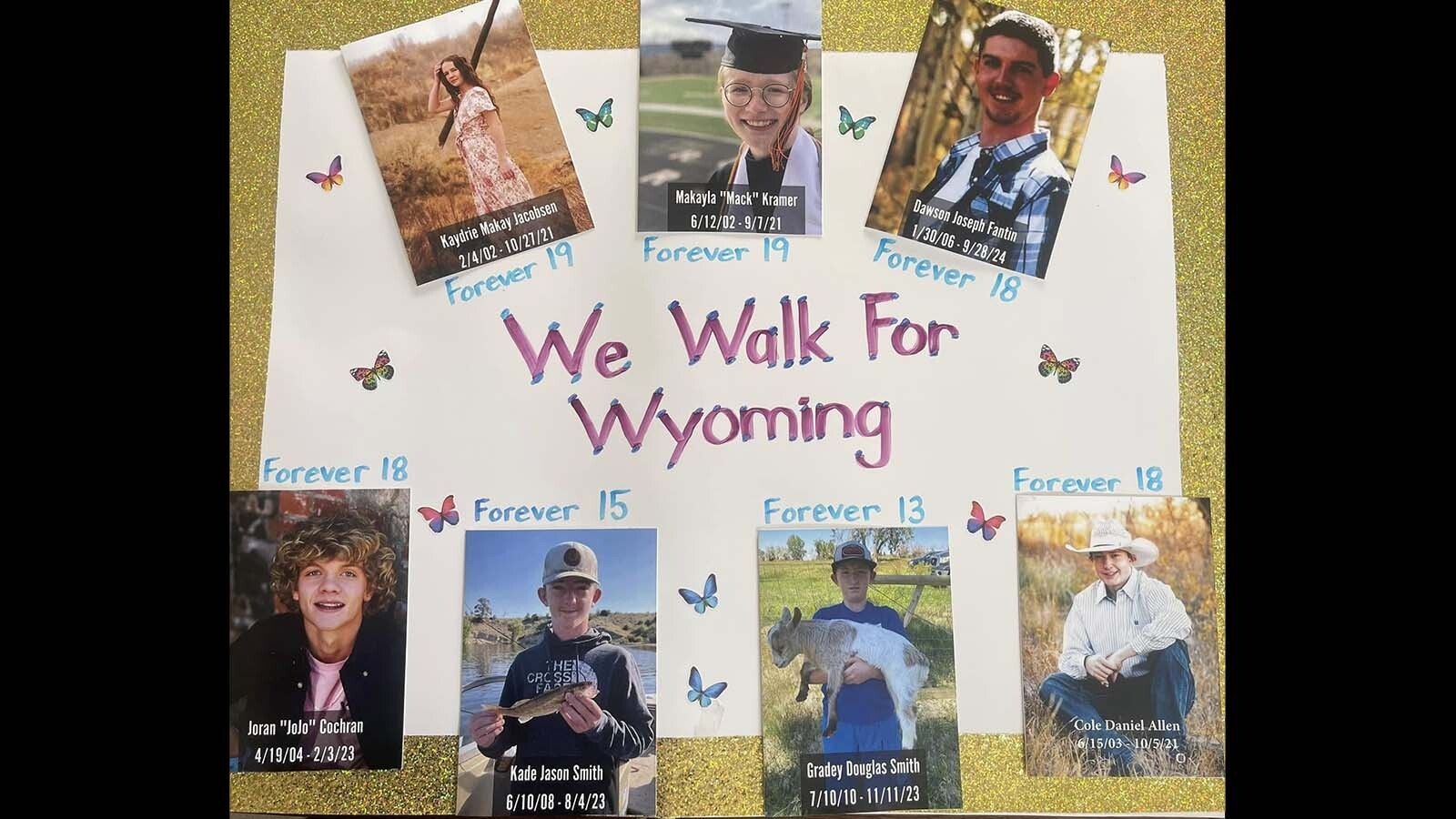

Cochran was one of 35 Sweetwater County residents to die by suicide in 2023, with 75% involving firearms. He was among more than a half-dozen Rock Springs teens to die by suicide between 2021 and 2024.

Cochran was one of 156 Wyomingites to die by suicide in a year when this state had the third highest per-capita suicide rate in the nation, according to data from Wyoming Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those figures have since grown more concerning.

Wyomingites in 2024 died by suicide in greater numbers than the previous three years, with most of those deaths happening among males using firearms, according to provisional data published last month the Wyoming Department of Heath.

Males accounted for 88% of resident suicide deaths in Wyoming in 2024, and about 72% of overall suicide deaths that year involved firearms. Roughly 12% involved hanging and over 8% involved poisoning.

It appears the state is taking notice.

Gov. Mark Gordan has made mental health a central focus of his second term, and last year rolled out a “Mental Health Roadmap” that includes state-funding for suicide prevention training programs like PROSPER.

Among other initiatives, Sweetwater County Prevention Coalition is promoting Man Therapy designed specifically to help men proactively combat suicidal tendencies.

From a statistical vantage, however, the problem does not appear to be getting better. This month, Rock Springs lost two more residents to suicide, including 30-year-old Austin Cave and 35-year-old Robert Todd.

Besides state efforts, the biggest encouragement, perhaps, is simply knowing that some Wyomingites are willing to fight for improvement for as long as it takes.

“I feel like we’ve dropped the ball as a whole and that we’re failing to help our community to realize and recognize how serious this problem is,” said Cochran, who remains an active organizer for suicide awareness in Sweetwater County.

“I was Joran's biggest supporter. I can't fight for him anymore, so I'm just gonna keep fighting in memory of him.”

Editor’s Note: Former Rock Springs High School administrators could not be reached for comment. The Sweetwater County School District 1 superintendent declined to comment for this story.

Zakary Sonntag can be reached at zakary@cowboystatedaily.com.