The Ferris Hotel is long gone from the streets of Rawlins.

It was once the elegant heart of social life in my hometown. Built by an early Carbon County copper baron and filled with Molesworth furniture, the Ferris featured a cafe that opened long before the sun rose.

Dad often took my brother, Mark, and me to breakfast at the Ferris when we were staying in town during the school year. I recall not wanting to crawl out of my warm bed into a cold pickup for the trip downtown. But Frank Miller – the best cowboy I ever saw or even heard about and the finest man I ever knew – wanted his sons to have a hearty breakfast, because there was work to do.

The dark street in front of the Ferris would be lined with battered ranch pickups that had a scant square foot of ice scraped from the windshield, just enough for the driver to see through. Loose hay from the feedings of the day before sprinkled the truck beds; the tire chains were still caked with frozen mud and ice, as were the thumb-busting handyman jacks, and coal shovels for digging out of snowdrifts.

There might be a stock dog or two in the bed of a truck, waiting for the boss to finish eating, and they’d bark a “good morning” at a couple of kids who walked past. Dad would say, “Don’t pet ‘em," and we’d go in for breakfast.

Inside the frosty windows of the Ferris the coffee shop was pretty modern, in contrast with the Gilded Age splendor of the rest of the hotel. Lots of formica and chrome on the counter and tables, and the chairs and booths were covered in blue Naugahyde. The place smelled like bacon, coffee and cigarette smoke.

There was room to accommodate maybe 50 hungry patrons, but the big, circular booth beside the front window was unofficially reserved for men who ran the ranches that surrounded Rawlins.

Dad’s contemporaries, 30-something cowboys and sheepmen who were scarcely a decade removed from the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific, would scoot around in the booth to make room for us. Mark and I were probably 6- or 7-year-old kids, but we would be welcomed to the table by name, and made to feel right at home.

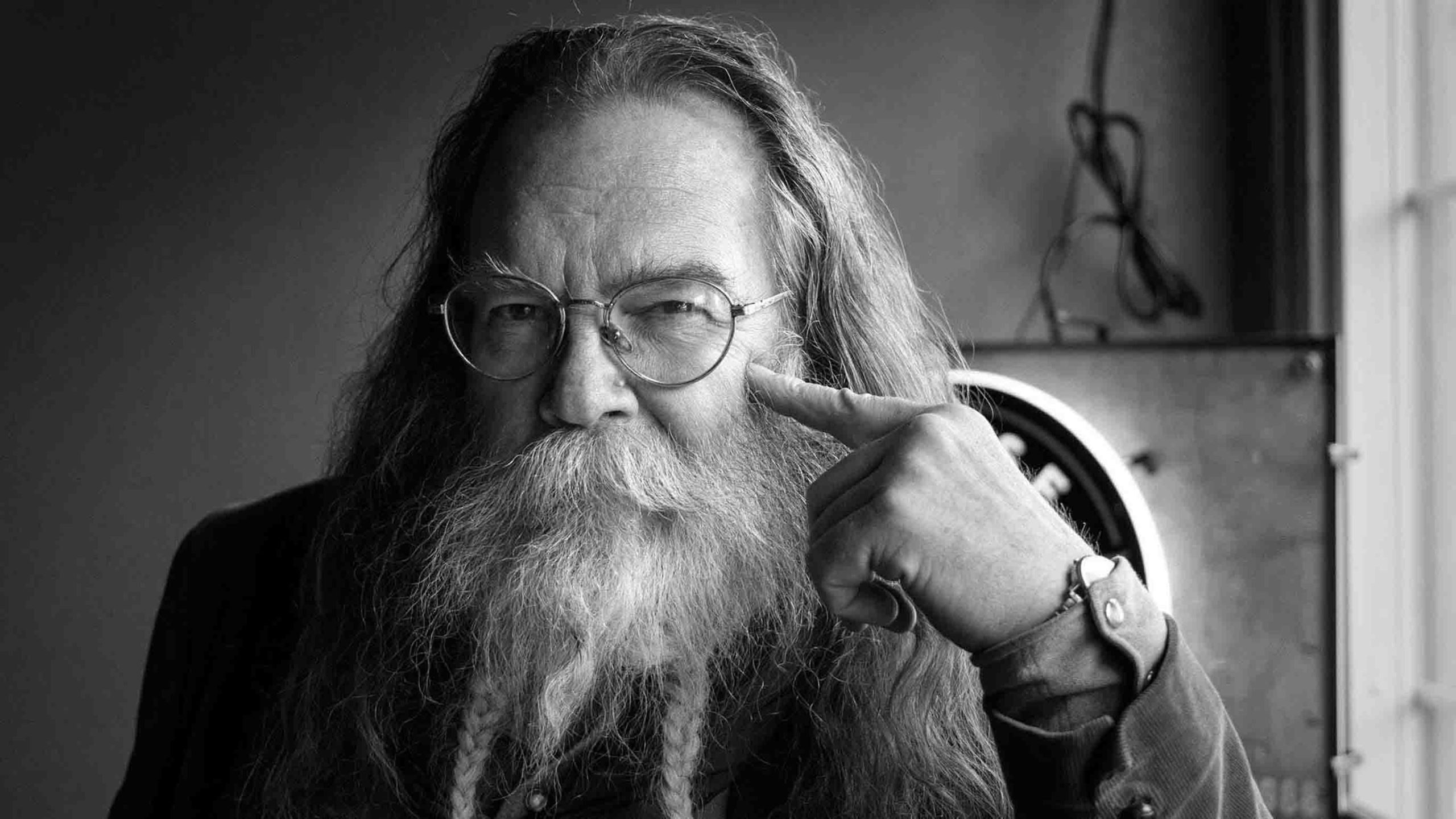

Anyone who spent the slightest bit of time in that country would recognize the names of these men: Grieve, Vivion, Espy, Peterson, Stratton, Sun. Rendle, Niland, Strand, Rochelle. Time in the saddle had weathered their faces and given them a certain way of walking.

The hatrack held their creased and sweaty Stetsons or wool ranch caps. They wore Pendleton shirts for warmth, over cotton pearlsnaps so the wool wouldn’t itch. Silk neckerchiefs were knotted loosely at their throats. They wore Levis with the cuffs rolled up, and five-buckle overshoes over their cowboy boots.

Shirt pockets held a tally book on one side, and a pack of cigarettes, a Copenhagen can or a sack of Bull Durham rolling tobacco on the other. The little paper tag on the drawing string of the tobacco sack looped over the lip of the pocket.

It would have been a breach of protocol to eat Rice Krispies or corn flakes at this table, so Mark and I ordered buttermilk pancakes, scrambled eggs and spicy link sausages that we dipped in syrup and ate with our fingers.

Talk around the table never touched on politics. It was all about weather, the cattle market, bankers, snotty broncs, and more weather. Nobody spoke ill of anyone who wasn’t at the table, but they teased and cussed each other mercilessly and got teased and cussed in return. It’s difficult to describe the camaraderie among them except by how they spoke.

Wives were mentioned with something approaching reverence. “Hardest workin’ gal on the outfit," “The brains of the family," “Don’t know what I’d do without her.” These were rough and dignified men who always stood when a woman entered the room, who pulled chairs out and opened doors, who never cursed around women.

Except for Mark and me, they are all dead now.

It was only later in life that it dawned on me that Frank Miller wasn’t merely taking his sons to breakfast. He was teaching us. He was introducing us to our tribe of neighbors who, over the years, would play such a large part in our lives. He was letting his friends instruct us by their example.

Dad was telling us, in no uncertain terms and without saying a word, “This is where you belong.”

Rod Miller can be reached at: RodsMillerWyo@yahoo.com