Relax, take a deep breath, this isn’t another column about politics. This column is about something much more important than mere politics. Let’s spend a bit of time talking about the human competitive spirit.

Although competition is part and parcel of the political process, it was not politics that occasioned this piece. What prompted me to write is the fact that I’ll watch my granddaughter’s last home hockey game this weekend. Maya Miller is a beast on the ice, highly competitive, and I’ll miss watching her create mayhem and havoc next year.

I used to coach kids in several sports – baseball, football, basketball and soccer. Over the years, I’ve blown my coach’s whistle at over a thousand young ‘uns from 5 to 15 years of age. Four of the kiddos were my own sons, and I wouldn’t trade the experience for all the ice cream in Farson.

When I’d get the teams together for the first practice of the season, I’d always tell them, “It’s not all about winning, we’re here to learn the game and have fun.” They’d invariably glance at me with a look that said, “Horseshit, coach. We’re here to win!” Even the 5-year-olds.

There is something in every human being, innate and not learned, that revels in competition, and that responds very deeply to victory. It’s hard-wired in our architecture, and it’s been there since the dawn of our species.

Try as we might to condition it out of ourselves, it’s coded too deeply: as big a part of us as walking upright and symbolic language. We are competitive beings, and we love to win.

The softer side of our nature grasps that cooperation among us has also helped us build our societies and our cultural organizations. But, when push comes to shove, we compete hard, and we play to win.

Participation trophies be damned. The rubble of history is full of second place winners. Humanity didn’t survive and advance by celebrating the runner-up.

Adam Smith wrote the seminal work, “Wealth of Nations," and it became the go-to text for competition in the marketplace, a cornerstone of capitalist thought. But that was the last of his many books.

His first book was “The Theory of Moral Sentiments” in which he explored a hypothetical Utopian world where human cooperation was the norm rather than competition, and exclusivity was shunned in favor of inclusion.

There were no winners nor losers in Smith’s theoretical world, just participants. He concluded that a system built on that ethos would ultimately produce stagnation and entropy among humans. Because it left no room for innovation, nor the search for excellence. It left no room for mankind’s growth through victory.

We, as humans, can’t go very far up the road relying on nothing but group hugs.

Charles Darwin, in “On Origin of the Species,” reached the same conclusion in evolutionary terms. His concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest – whereby competition for survival results in clear winners and losers – likely sets on edge the teeth of proponents of DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion). But these are governing principles in the closed system that is our world.

Survival of the fittest, bleak as it may seem to some, is the ultimate meritocracy. We ignore it at our mortal peril.

So, on the eve of my favorite granddaughter’s last home hockey game, I’ll hoist one to the human competitive spirit, and to the drive, determination and sacrifice that that create winners. Join me if you get more satisfaction from competing than from merely participating.

Game on! And in the immortal words of Yogi Berra, “It ain’t over ‘til it’s over.”

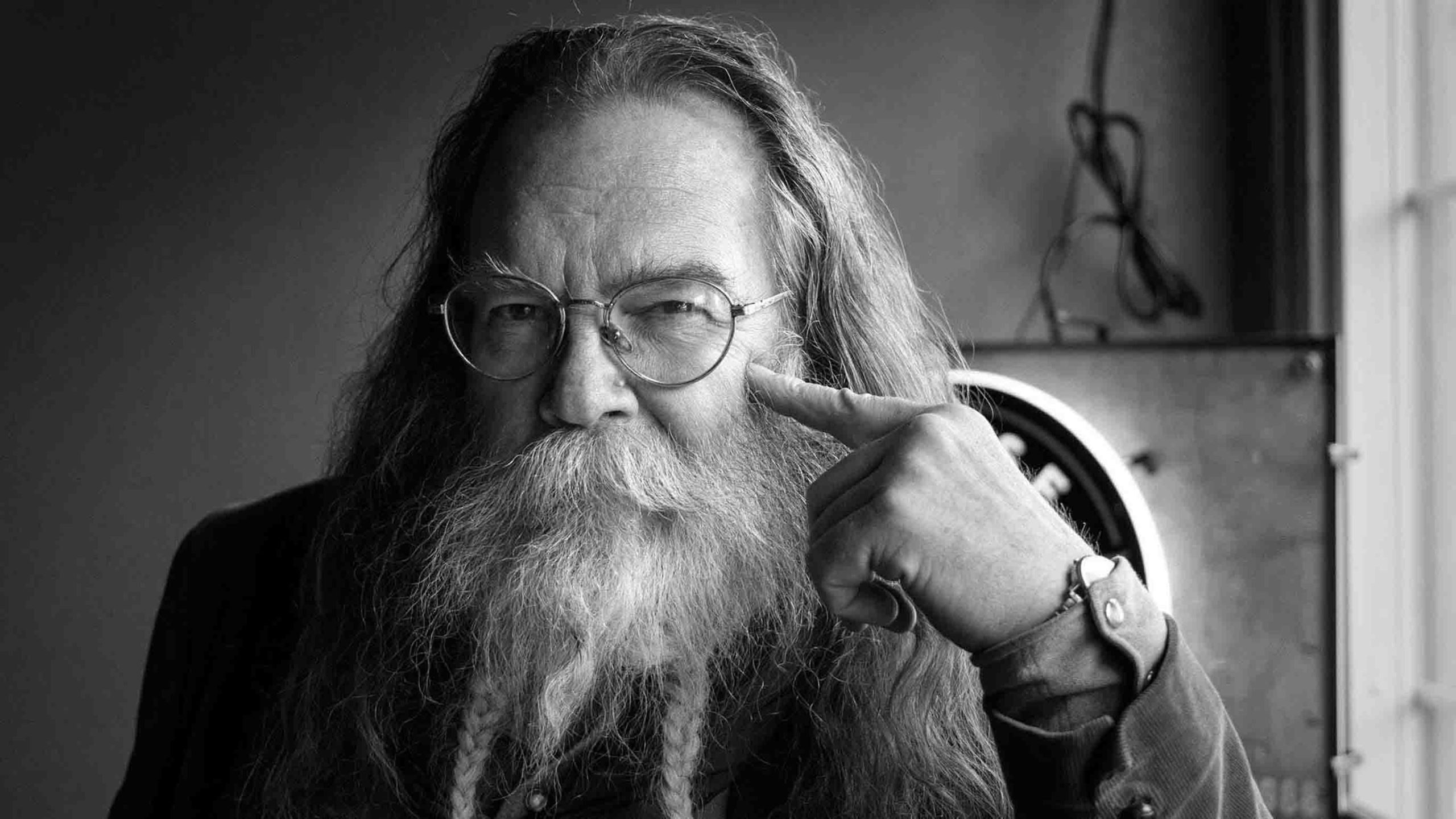

Rod Miller can be reached at: RodsMillerWyo@yahoo.com