On May 29, 1931, in Newark, New Jersey, Amelia Earhart climbed into the cockpit of an autogiro, an experimental aircraft, to embark on a transcontinental trip across the United States. She had set an altitude record of 18,415 feet in an autogiro the month before, and now she wanted to become the first pilot to make such a journey in the autogiro. During this adventure, she stopped at several Wyoming towns.

Beech-Nut Packing Company, the chewing gum manufacturers, owned this craft built by Pitcairn, an open-cockpit propeller airplane with 45-foot-diameter rotor blades above, that could take off and land like a helicopter. Earhart’s husband of three months, promoter George Palmer Putnam, made arrangements for her to fly the vivid green autogiro. Some pilots called it “the Black Maria” because of numerous accidents, but Earhart told interviewers it was “the answer to an aviator’s dream.”

The autogiro required refueling every couple of hours, and Earhart, accompanied by mechanic Eddie de Vaught, sometimes made ten stops in a day, traveling at an average speed of 80 miles per hour. Her 76 stops during that early summer trip included Cheyenne, where she arrived on June 2. The Wyoming State Tribune called the aircraft a “weird windmill.” She flew to Denver, Colo., the next day, and then returned to Cheyenne. Additional Wyoming stops included Laramie, Parco (now Sinclair), Rock Springs, and LeRoy, near Fort Bridger. Crowds numbered in the thousands to see her in Cheyenne and Rock Springs. The Laramie Republican Boomerang’s front-page report touted her “jovial” attitude during her 20-minute refueling stop there on June 4, explaining that she greeted “even the countless school children who gathered about her feet when she descended from the high cockpit.” The Denver Post reported that people stood on rooftops there to watch the “sandy-haired sky goddess” flying the rotorcraft.

Pilot Johnny Miller became the first person to cross the country in an autogiro, so Earhart planned a return trip so she could set a round-trip record instead. However, she crash-landed in Abilene, Texas, on June 12. She steered into an open area to avoid onlookers, and she said the wind had stilled beneath her wings, but she was formally reprimanded for pilot carelessness. She was not banned from flying, however, and her husband booked her on two more autogiro tours.

On May 20, 1932, Earhart piloted a single-engine Lockheed Vega in a solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, becoming the first woman to do so. But she had flown the ocean before.

Her first famous Atlantic crossing occurred when she rode as a passenger in a Fokker trimotor, the Friendship, in 1928, becoming the first woman to fly across the ocean, and gaining fame as “Lady Lindy,” a nickname that recognized the achievement of Charles Lindbergh, the first pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic on May 20, 1927.

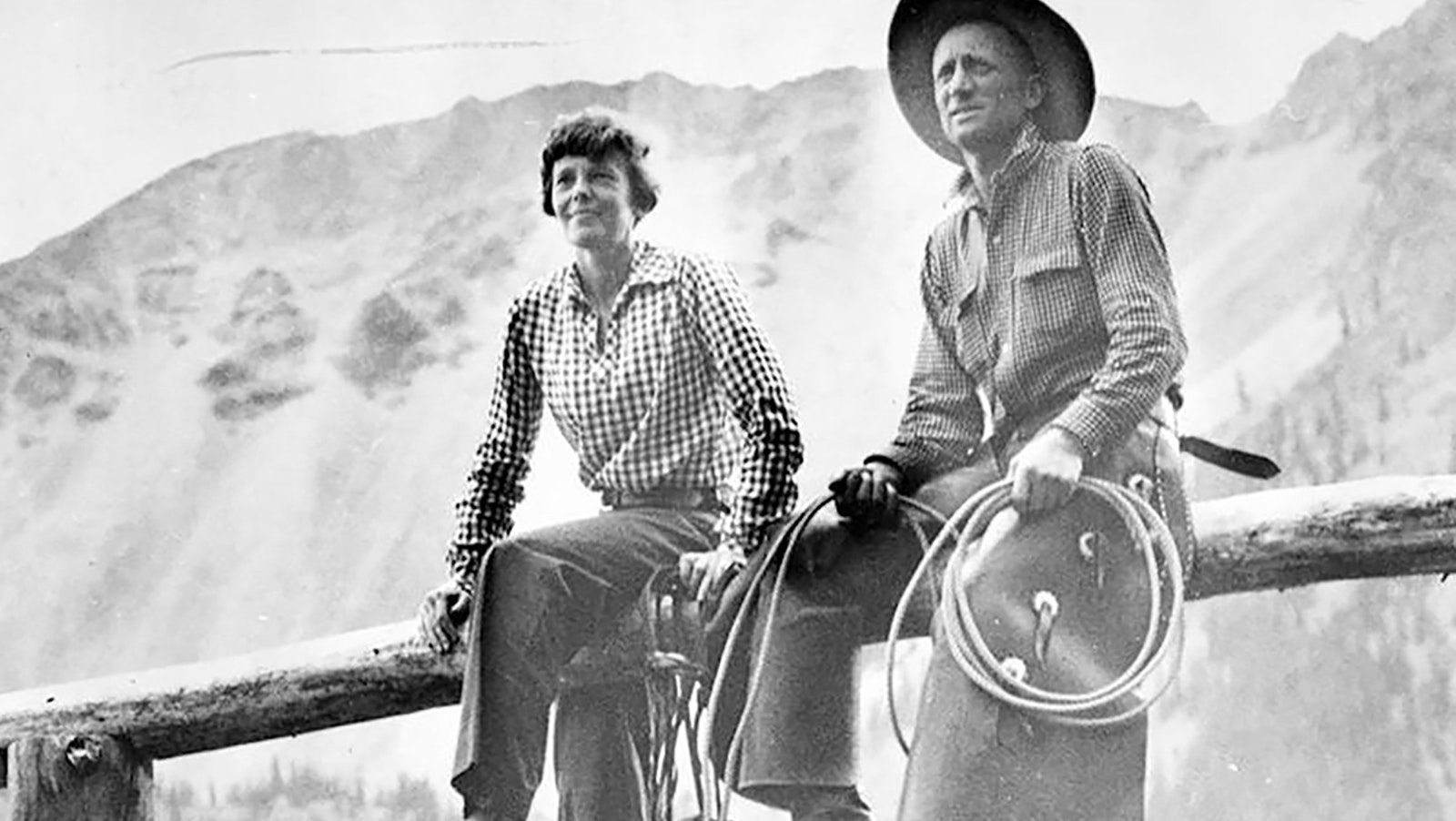

Putnam, longtime friend of Carl Dunrud, who had guided him on a 1921 pack trip in Yellowstone National Park and who owned the Double Dee Ranch near Meeteetse, vacationed at the dude ranch in 1934 with Earhart. They were in the process of building a log cabin overlooking the Wood River when she began her ill-fated 1937 round-the-world trip, piloting a Lockheed Electra, and planning to become the first pilot to accomplish the feat. By early July, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, had logged 22,000 miles, but after departing from Lae, New Guinea, headed to Howland Island, just weeks before her fortieth birthday, they were lost.

When Earhart did not return, the heartbroken Putnam spearheaded search efforts for her. Work on the cabin ceased. The mystery of their disappearance remains unsolved, although costly searches by various groups continue, sometimes with reports of evidence to support differing theories.

There was still “a log or an impression of a log on all four sides” of the cabin site a few years ago, according to Meeteetse Museum Executive Director Alexandra Deselms.

In late July, near the time of Earhart’s birthdate of July 24, the museum hosts an annual tour of the Double Dee, which is part of the Shoshone National Forest and often includes a reenactor playing the role of Earhart. High clearance vehicles are necessary because of the rugged terrain.

More information about the tour and the cabin location are available at the museum. The cabin site is “on the parking lot side of the river, past the Tumlum Mine and behind the Dollar Cabin and a Forest Service cabin,” probably about a mile from the old mining town of Kirwin.

Carl Dunrud’s sons, Jim and Richard, remembered Amelia Earhart with fondness in a 2005 telephone interview and recalled her generosity and graciousness. Their mother Vera told them Amelia loved the “restless sound” of nearby JoJo Creek. She sent gifts to the youngsters at Christmas and sent two coats to Carl Dunrud before her world flight. The leather flight jacket and a buffalo coat from actor William S. Hart later became part of the collections at the Buffalo Bill Center for the West in Cody.

Lori Van Pelt is the author of Amelia Earhart: The Sky’s No Limit. She can be reached at lori.vanpelt@aol.com