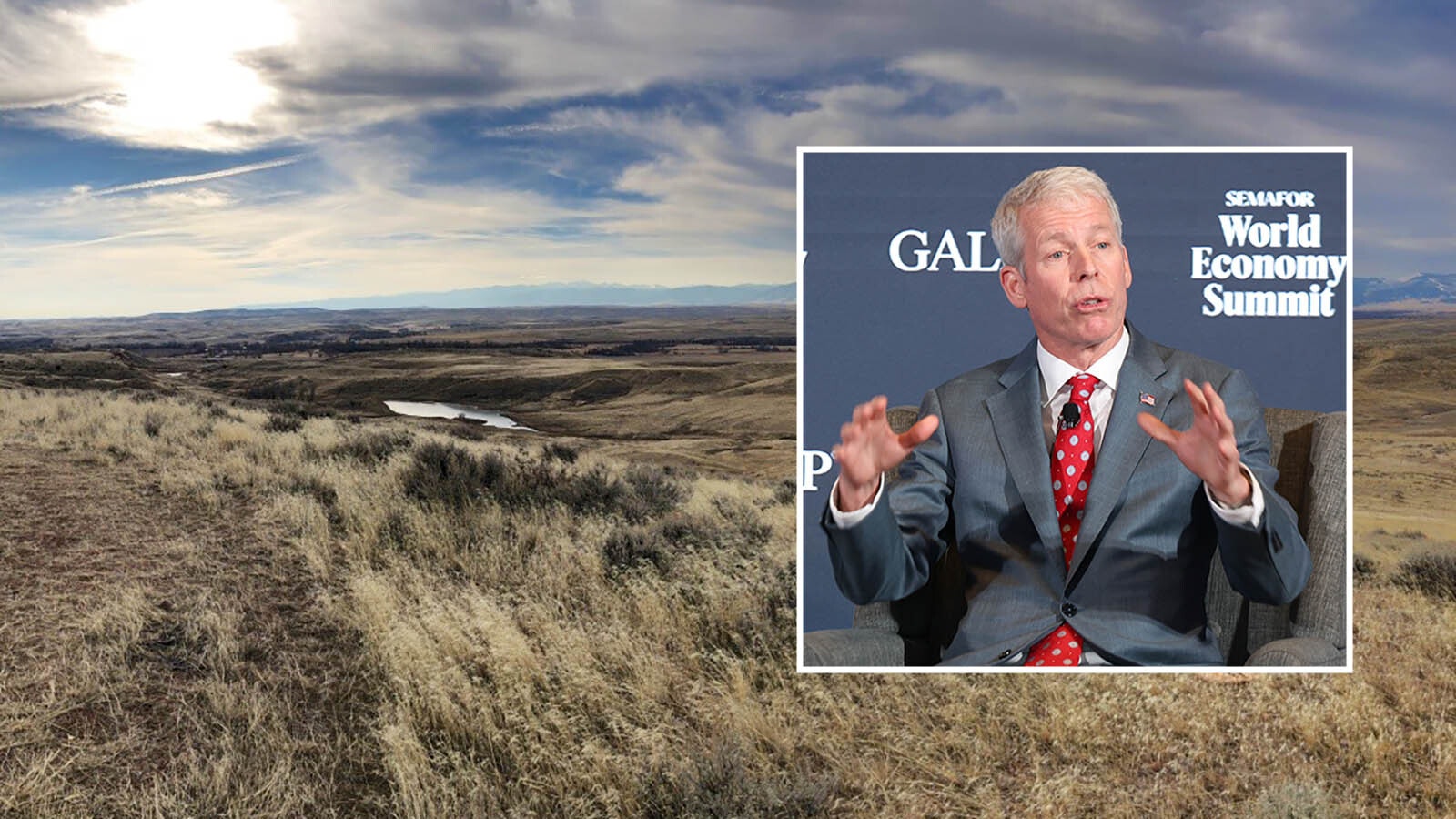

People driving on the highway in and out of Kemmerer can see construction work underway at the site of TerraPower’s new Natrium reactor.

But what they’re seeing is not the nuclear plant itself.

Instead, what’s under construction is a sodium test and fill facility for the future plant, the first step of many to come before the nuclear plant will come online sometime in 2030, according to projections.

Bill Gates founded TerraPower and was in Kemmerer in June for a ceremonial groundbreaking for the plant.

The test and fill facility is a key step in building this novel nuclear plant, a first of its kind in the United States. It’s where Bill Gates-backed TerraPower plans to test out and prove a first-of-its-kind nuclear cooling system, a process expected to take about a year.

“Sodium is a metal, and at room temperature, it’s a solid,” TerraPower’s Director of External Affairs Jeff Navin. “When you heat it up a bit, it becomes a liquid, and that’s what the coolant in our reactor will be.”

Before any of that molten sodium metal goes into the coolant facility, all the components of the facility must first be tested. That will ensure there’s no reactivity with the sodium, and ultimately, that there are no unexpected surprises when the nuclear part of the plant finally comes online.

“That work’s going to continue through next year,” Navin said.

In the meantime, TerraPower’s construction permit for the actual nuclear plant is in the hands of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, undergoing an 18 to 24-month review process.

The 3,000-page application is something TerraPower has already been working on with NRC for years, with white papers going back and forth between them to answer NRC questions about this novel approach. The papers have explained and described every aspect of the Natrium plant’s expected operation in excruciating detail, so that when the plant is finally operational, there should be no surprises for anyone.

Less Likely To Melt Down

The premise behind TerraPower’s Natrium reactor is that a sodium-cooled reactor will be less likely to melt down than conventional nuclear reactors. The boiling point of sodium is much higher than water — and much higher than the reactor temperature. All of that means there should never be a situation where the coolant can boil or vaporize away.

The system also doesn’t need to be pressurized to work, the way water does, eliminating another potential failure point.

But there is one caveat to that. Liquid sodium can catch fire if exposed to air or water.

And that’s where the test and fill facility comes into play. It will be used to game out every possible weakness before the nuclear reactor goes online.

“Once the test and fill facility is operational, then we’ll have people working there, testing components, working with the sodium, making sure that it’s acting in the way we anticipate that it will,” Navin said. “Then, in 2026, we anticipate that we’ll start working, we’ll have our license from the NRC, and then we’ll start working on the actual nuclear reactor at the site.”

Even then, however, the plant will still not be operational. TerraPower will apply for it’s operational permit the following year, in 2027.

“That will take a couple of years as well,” Navin said. “It’s a two-part licensing process. The first is to build the reactor, and the second is to operate it.”

Many Moving Parts

Because the plant is unprecedented, there are lots of additional moving parts happening concurrently with TerraPower’s construction of facilities.

Among the most critical is standing up a domestic supply of High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) at commercial scale, which doesn’t presently exist in the United States.

That’s going to be important not just for the TerraPower Natrium plant. There are now more than 20 U.S. companies developing various advanced nuclear reactor concepts that will need a higher grade of enriched uranium.

The conventional nuclear fleet runs on uranium-235 enriched up to 5%, but HALEU is enriched beyond that, in the range between 5 to 20%.

Department of Energy projections suggest America needs more than 40 metric tons of HALEU by the end of this decade for other similar nuclear plants already on deck, working their way through the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s processes.

Idaho National Laboratory is working on two chemical processes that can provide some HALEU in the near term. These two processes recover highly enriched uranium — greater than 20% — by recycling used nuclear fuel. The product can then be downgraded to make HALEU fuel.

For the longer term, Department of Energy is working with an enrichment facility in Pinkerton, Ohio to build a demonstration plant for the enrichment of uranium hexafluoride gas, which can be used to produce HALEU in the large quantities that will be required.

Once that demonstration is complete, the technology will be available for commercial deployment.

Two appropriations bills have already kicked funds into these HALEU manufacturing projects, Navin told Cowboy State Daily, one at $700 million and another at $2.7 billion.

“Once that program gets stood up, we’re hopeful that we’ll be able to use a domestic source for our fuel,” Navin said. “But that is still a little bit of a question mark as to how quickly the government’s going to be able to move, and how quickly the private sector will respond. But we’re continuing to operate under the assumption we’ll have the fuel available, and we can start the reactor in 2030.”

The Ohio plant can already produce about 900 kilograms of HALEU, Navin said.

“And then Uranco has a facility in Eunice, New Mexico, that can currently produce LEU, that they, we believe, will apply to produce high assay, low-enriched uranium as well.”

Once the HALEU is produced, it would then head to North Carolina, where there is a fuel fabrication facility that can manufacture the fuel rods that will go into the reactor.

Wyoming Uranium Will Get Tapped

While HALEU production is unlikely to happen in the Cowboy State any time soon, companies like Uranium Energy Corp. are already ramping up Wyoming production of uranium to send to Ohio.

“Neither Ohio nor New Mexico have any commercial production of actual uranium,” Navin said. “So, our hope with UEC is that we can have not just this plant in Kemmerer, but subsequent plants as nuclear continues to grow, and restart the uranium mining industry in Wyoming.”

With the largest deposits of uranium in the United States, and a long history of mining, the Cowboy State is ideally positioned to capitalize on the comeback of this ore.

“We see this as an opportunity not only to produce electricity in Wyoming from nuclear power, but we can use it as a way to increase demand for uranium, and we can get some more of these uranium mines that have been mothballed in the state, bring them back into production.”

Navin added that he would support HALEU production in Wyoming in the future.

“I know there is some interest from folks looking at that possibility” he said. “And we would certainly fully support and welcome that. But it probably couldn’t be ready for the first core load, just because of the time frame it takes to get such facilities up and running.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.