Myron Harrison remembers tagging along with his father on house calls.

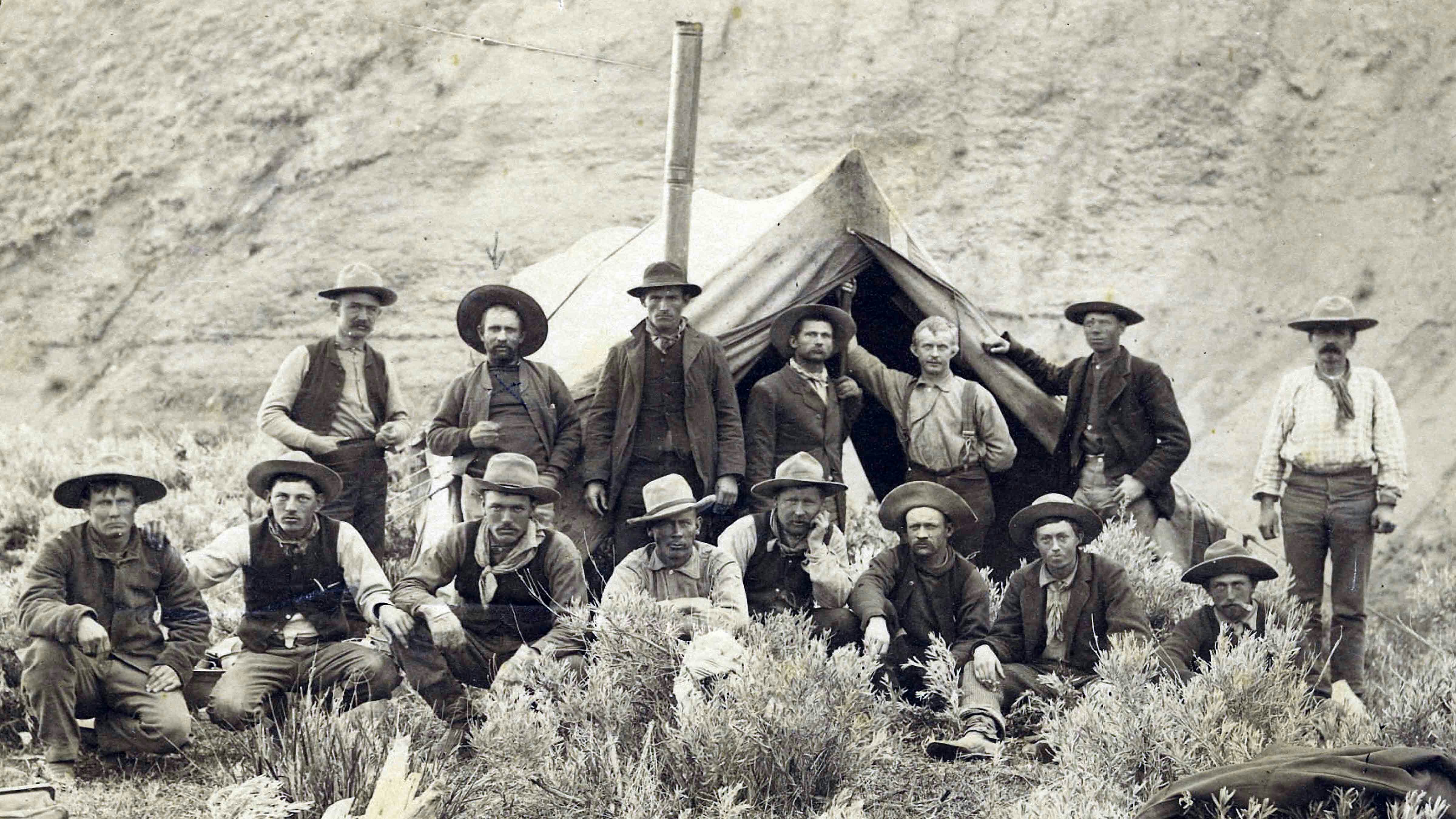

It was the mid-1950s, and Dr. George Myron Harrison was a small-town doctor in rural Sweetwater County. This meant Dr. Harrison had to do it all, from delivering babies and taking out spleens to making house calls in coal mining camps with his young son in tow.

Those house calls left an impression on young Myron, who can still recall the abject poverty of the camps and the tiny, shoebox-sized, drafty wooden homes with dirt floors that housed the miners and their families.

He appreciated his dad’s kindness as he examined sick children before administering a shot of penicillin.

Dr. Harrison was synonymous with penicillin, Myron joked, which he believed cured most ailments.

That Myron also became a physician is likely a testament to the impression those early years had on him, he said, though admittedly his career choice was a result of not knowing “what the hell I wanted to do.”

His father, who passed away in 1989 at the age of 74, never put any pressure on him to follow in his footsteps, Myron said.

The one house call that sticks out the most with him is the time Harrison was called out for an emergency on an oil drilling rig in rural Rock Springs.

It was a Sunday morning, Myron recalled, and he and his father drove through miles of desolate terrain and sagebrush just to get to the rig.

A worker had gotten his leg entwined in a Kelly bushing so tightly that he couldn’t move. The doctor had no choice except to amputate the man’s badly shattered leg to cut him loose.

Young Myron purposefully avoided watching that practical procedure until it was over, and the man was rushed off to the hospital in a waiting ambulance.

This was just part of the day-to-day job, which back then was an around-the-clock position, Myron said.

The family lived a block from the old Memorial Hospital, where Harrison went often at all times of the day and night to deliver babies and tend to patients with any number of health problems.

“He learned it all before you could just call in a specialist for everything,” Myron said.

Real Education

In many ways, Dr. Harrison’s early life prepared him for his eventual career.

He was born in Springville, Utah, in 1915. His mother, Alta Crandall Harrison, died when he was 7. Harrison was then shipped off to live with an uncle in Salt Lake City because his father, George, was an engineer on the Union Pacific Railroad and was gone for long periods of time.

Later, his uncle loaned Harrison money to attend college at the University of Utah, followed by medical school in Chicago, where he graduated in 1941 before joining the U.S. Army as an air medic.

It was in the Pacific Theater of World War II that Myron said his father got his true medical education working on “flying ambulances” patching up soldiers. He also contracted dysentery during this time, which led to bowel issues that plagued him for the rest of his life.

After the war, he took a job as a company physician for the Union Pacific Coal Co. in Superior.

He married Mary Straight, a teacher, in 1946. A year later, the couple moved to Rock Springs, where Harrison left the railroad and set up his own practice, and the couple went on to have six children: sons Myron, Richard and Robert and daughters Gwen, Maribeth and Carolyn.

Like Imelda Marcos

As the oldest, Myron’s outings with his dad were rare times that he got to spend with a busy father who seemed to be always working or golfing on his precious days off.

Apart from his proclivity for prescribing penicillin, Dr. Harrison was also well known for his snappy golf outfits and shoes, and for picking up the sport at a time when few people played it. He was the first member the Rolling Green Country Club in Green River.

Myron said his father was drawn to golf after seeing Bob Hope and Bing Crosby entertain the troops during World War II.

“Both of them were avid golfers and were joking all the time and having a great time,” he said. “My dad was so impressed with that that he came back to the United States and picked up the game.”

His dad even had a little No. 1 tag from the course that he put on his golf bag, and one of Myron’s favorite photos of his father is posing with that bag in one of his dapper golf outfits.

“He had a closet with 50 alpaca sweaters in a rainbow of matching colors with matching golf shoes,” Myron said. “He was like Imelda Marcos.”

As a golfer, Dr. Harrison wasn’t particularly good, but he loved being out there golfing.

“Those were his hours of relaxation because he was always on call, 24 hours a day for most of his life,” Myron said.

Doctor Of The People

Apart from his snazzy golf outfits, Dr. Harrison was known by many as a kind, generous doctor who didn’t discriminate when it came to his patients, even when it landed him in hot water.

During Rock Springs’ more notorious period in the mid-1970s when prostitution, drugs and corruption ran rampant during the height of a construction boom when the Jim Bridger Power Plant was being built, the doctor tended to the prostitutes who often came into his downtown office sick, exhausted and often needing various medications.

He had a heart for these women, Myron said, as he did for anyone who had a hard life and needed care.

“He would try to help whoever came in,” Myron said.

Good Man

It was only one setback in a long and storied career where he’s remembered by many in the community as a kind doctor who genuinely cared.

Locals like Cindy Netherton recalled the many times Harrison helped her family.

Today at age 55, she still gets emotional and tears up when she thinks of those visits and Dr. Harrison’s kindness toward her mother, Roberta, who was a single mom of two girls.

“We were so poor,” she told Cowboy State Daily. “I know my mom was on assistance, but I know for sure they gave us a lot of free treatment.”

Along with the free care, Harrison also stepped in to help her mom when Netherton was a rowdy teenager, helping find her proper counseling. He also helped her when she had a miscarriage as a teen and was able to help diagnose her mother’s brain tumor early enough to get her care.

“My mom did pass away years later, but the fact that he caught some of her symptoms as early as he did with her seizures, I might not have had her as long as I did,” Netherton said. “I will always be grateful to him for that, and all the penicillin.”

Stacie Rock Anastos also shared similar memories about the doctor’s generosity.

She recalled her father’s back surgery in the early 1980s when she was still in first grade. It was the holiday season, and the family was struggling because her dad’s disability payments hadn’t begun paying out when she and her two siblings got sick.

It was snowing heavily that day, so her mother couldn’t drive and instead called the doctor’s office for advice. The nurse took a message and said she’d call back. Within a few hours, however, Dr. Harrison was at their door with penicillin shots in hand.

Anastos said the doctor spent some time visiting with her father and refused any form of payment when her mother offered.

“He told my mom it was on him,” she said. “That’s just the kind of man he was. He was an outstanding doctor, but he was also a phenomenal human being.”

Good As It Gets

Dave Bernatis also has fond memories of Dr. Harrison to share.

“He was as good as they get,” Bernatis said.

Not only did Harrison deliver him as a child and make house calls, but he has a litany of scars by which to remember the good doctor, including a work accident from 1976 involving a broken finger that Harrison stitched and splinted up before sending Bernatis back to work.

“He was awesome,” he said.

Dean Muir agrees.

“He was one of two doctors who truly cared about his patients,” Muir shared on Facebook. “If you had strep, he treated the whole family and didn't charge everyone. He was about caring and making people well.”

Myron isn’t sure how many people his father treated for free, but said the community repaid his kindness with pastries and other presents during the holidays, including, the family’s favorite Slovakian cakes.

For years, up until the 1980s, Dr. Harrison charged $3 for an office visit for which Myron chastised his father not charging enough money. But the doctor wasn’t too concerned, nor was he overly worried if people couldn’t pay.

“That was just the kind of guy he was,” he said.

For years, he worked out of a two-story office on Broadway Street where his exam rooms were cordoned off with curtains, not doors, which many of his patients still remember.

Memory Lives On

Ultimately, however, that dysentery he contracted during World War II got the best of him.

Throughout his life after that, Dr. Harrison struggled with sensitive bowels and wasn’t able to achieve proper nutrition, Myron said, because he couldn’t eat a lot of things.

At dinnertime, Myron remembered his dad dunking his bread into a glass of milk because it was one of the few meals that didn’t upset his stomach.

Harrison spent about four months in the hospital following a bowel surgery, which didn’t go well, Myron said. He died Dec. 28, 1989, at age 74, the same year he retired.

“He was sort of the quintessential doctor,” Myron said of his father. “Guys like my dad were still around in the 1980s, but they were disappearing quickly as modern medicine crept into cities.”

But for the longtime residents of Sweetwater County, Dr. Harrison’s memory lives on as a kind man and doctor who genuinely cared for his community and patients.

Jen Kocher can be reached at jen@cowboystatedaily.com.