Park County Archives Curator Brian Beauvais has worked to combine two of his passions — history and exploring the outdoors.

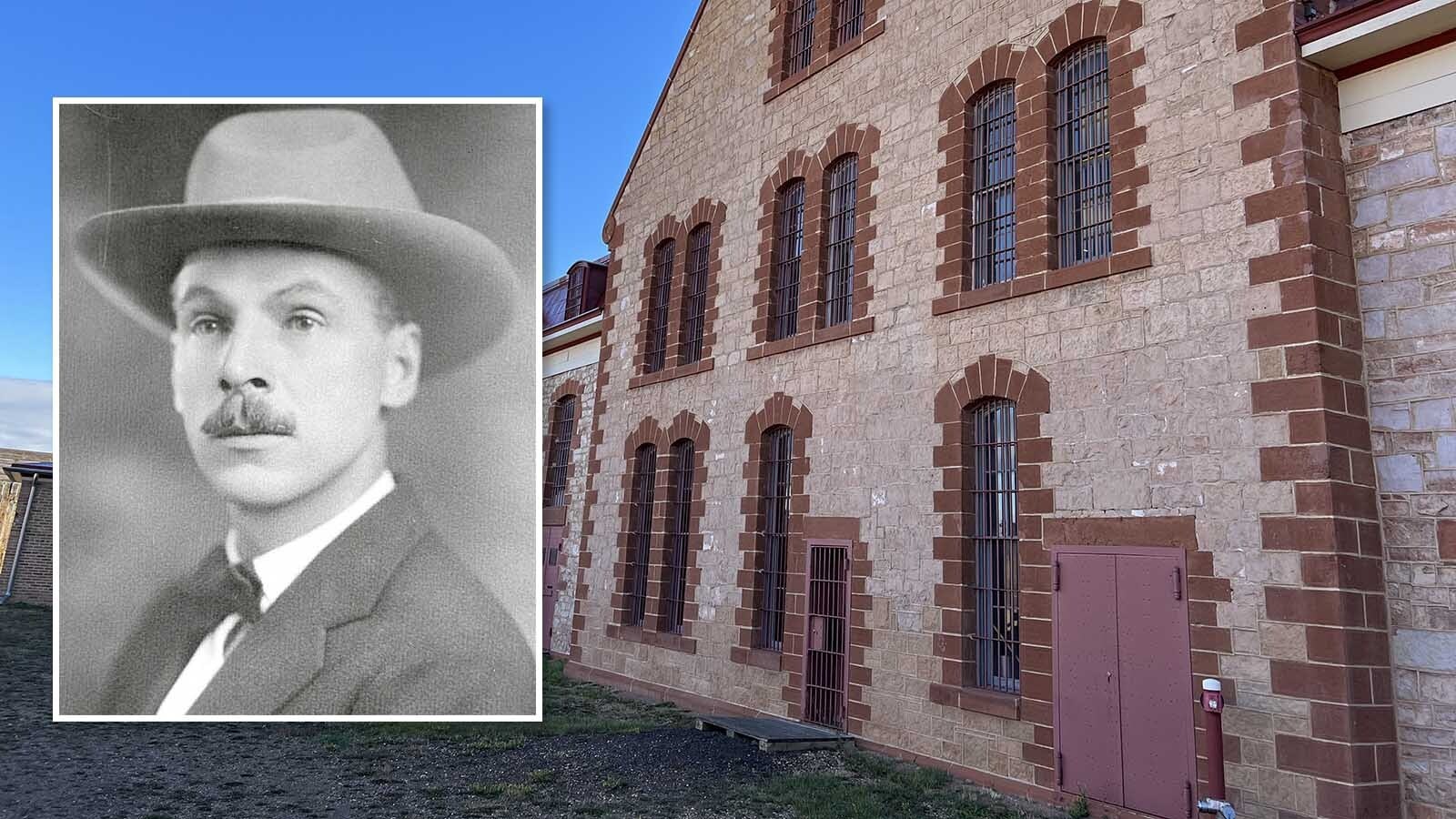

It’s what led him to the photos and diaries of geologist Thomas Jaggar four years ago. Jaggar worked as an assistant under geologist Arnold Hague, who began the first detailed survey of Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding areas in 1883. Jaggar came to the area in 1893 and 1897 to help survey the lands just east of Yellowstone, mainly in the Absaroka Range.

“He is not really well known around here, but he was a volcanologist,” Beauvais said. “He was really active with the U.S. Geological Survey in the early 1900s. He graduated from Harvard in 1893, and he came out on this trip as the assistant of Arnold Hague.”

Jaggar’s diaries include information on the area, survey records with geology notes and photos, which he developed right in the field. After reading a book about Jaggar that’s housed in the Archives, Beauvais took an interest in his photographs.

He traveled to Denver in March 2020 to the U.S. Geological Survey Library to get copies of Jaggar’s original diaries, as well as the photos that are housed there. The day after gathering the information the library shut down due to COVID.

“I got started on this because I've always loved his photos of the outdoors around the Absarokas,” he said. “The diary is really cool because it mentions the South Fork, Sunlight and a bunch of places around Park County, along with who he encounters and what he's looking at.”

With things shut down thanks to the pandemic, Beauvais decided he wanted to find where some of the photos were taken and take his own shot to look for differences.

“It was a project for myself to try to rephotograph these because a lot of them are not super remote,” he said. “They're good day-hiking objectives and it was a good excuse to get outside, go to these places and see how the landscape is changing or not changing.”

Not Without Its Challenges

Beauvais tries to take photos in August and September when Jaggar himself was in the area, but the project isn’t without its challenges. Some of the original pictures are mislabeled, making them impossible to find. Others were taken on what is now private property.

And while many of the rock formations have remained the same, there has been erosion in some areas. Many spots are covered in much more vegetation than in the late 1800s as well.

“In some photographs you can see the erosion of an entire mountain range on a very small scale,” Beauvais said. “Or for example, when he came through in 1893 at the confluence of Little Sunlight and Sunlight, a forest fire had just ripped through the area. Now it's all regrowth, so it's a lot of dense cover that doesn't really make for great photos.

“Some you just can't rephotograph at all, because in 1893 you can see these big, open meadows and now it's just all overgrown.”

Jaggar also took some photographs at the base of a rock glacier because he was really interested in how a stream there emerged out of the rock.

“I went up there a few years ago to get the photos,” Beauvais said. “So when he was there in 1893 he was probably on a good 20-30 feet of snow and ice on Aug. 12. I went up there a few years ago, and there's just no ice left. It's completely a rock glacier. That makes it hard to rephotograph because he was up 20-30 feet higher and I can't get up there.”

Beauvais does note that many things have stayed almost exactly the same, including a dead tree in a photo of Ishawooa Canyon that is still there today.

“It's just astounding to me that a dead tree in 1893 is still standing as a dead tree,” he said. “I mean, how old are these trees? It makes me think, when I gather dead logs for a fire, am I burning something that's 500 years old?”

Finding Each Location

Before traveling to a site, Beauvais goes to Google Maps to drop a pin so he can follow the GPS coordinates. Then he hikes to the location and tries to calibrate exactly where he needs to stand to get the photo. Sometimes there could be a tree or other obstacle in the way, but Beauvais tries to get as close to the original location as possible.

“The rocks haven't moved,” he said. “So in some of the photos, I can get to the exact spot because the rocks help me line it up. Other times I just have to guess more, and I don't really know if I'm 100 yards off versus 300 yards off versus further.”

While not a trained photographer, Beauvais brings a DSLR camera to photograph the sites. He said many of Jaggar’s photos aren’t the best quality either, but the goal for both men – documentation of the area.

“They're not Ansel Adams photographs,” he said. “He's interested in geology. Some of them are close-ups of rocks, which I can't rephotograph because I can't be up in a place for a week to try and find the exact rock.”

Beauvais has rephotographed 30 of Jaggar’s images so far, but he’s hoping to get at least 20 more completed by the end of September. Most are located at the head of Rattlesnake Creek, up Sulphur Creek, down near Camp Creek and by the Shoshone River.

“Last week I was going to go up Sulfur Creek and Sunlight and take some photos, but if the smoke is bad it's not worth the time and effort,” he said. “I mean, even though they're just documentary photographs, I still need to have a good product to show. I can't show people smoky photographs where you can't see anything. So hopefully the smoke clears and we can do some of that.”

Pack Trip And Project Future

While many of the photos are accessible on day hikes, there are some that take much longer to get to. So Beauvais asked his friend Meade Dominick of the 7D Ranch last year if he would lead him on the trip up the South Fork, over Marston Pass, down into the Thorofare, up Pass Creek, over Ishawooa Pass and down Ishawooa Creek back to the South Fork.

To help offset the cost, Beauvais applied for and received a research grant from the Wyoming Historical Society for the trip. Unfortunately, when it came time to go in early August, Dominick was injured, so Silas Ward and Spencer Strike, who work for the 7D, took Beauvais and his friend Corey Anco on the trip. There were 18 photos along the route to reshoot.

“I didn't really want to go backpacking by myself through there, so I needed someone to help me cover ground,” he said. “The trip lasted six days and covered more than 70 miles of trail (and non-trail). The whole point was to cover ground and get to Jaggar photo locations that were too remote for me to reach on a simple day hike.”

As part of the grant, Beauvais will write an article about Jaggar’s photography for the Annals of Wyoming: the Wyoming History Journal. He also hopes to write something for Yellowstone Science about documenting landscape change through rephotography. And early next year he’ll give a talk about the trip and his overall findings at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

“One of the cool things about this project is it documents how things have changed, but it also just documents that a lot of this stuff is exactly how it was 130 years ago,” he said. “We complain about landscape change or development around Park County, but these geological features are the exact same things as they were seeing 130 years ago, probably 200 years ago. It just hasn’t really changed all that much.”

His long-term goal is to republish Jaggar’s diaries with his updated information included.

“I’d like to add historical commentary,” he said. “And my friend Hank Hessler and his wife Cheryl are both retired National Park Service geologists in Yellowstone, so it'd be nice to get their geology commentary too.”

Beauvais also hopes the project will make people realize there is more than one way to conduct historical research.

“I’d like folks to know that learning about the past doesn’t always have to take the form of lonely reading and studying dusty old documents – it can involve adventure and exploration and getting outside to see the world,” Beauvais said. “I’ve learned so much about the geography and landscape of the Absarokas and Northwest Wyoming in trying to find the exact spots where Jaggar took all these photos. Some are in super remote locations, others are not. But it’s fascinating to document how the landscape has or hasn’t changed over the past 130 years.”

Beauvais has put Jaggar’s photos on a GIS map that can be found on the Park County Archives website. For the ones he’s been to, his photograph is included with the Jaggar original.

“I know I'm not going to get all of them, just because there's only so much time,” he said. “I can't just leave whenever good photo conditions come around. But I've got a lot of them, and I feel good about it.”