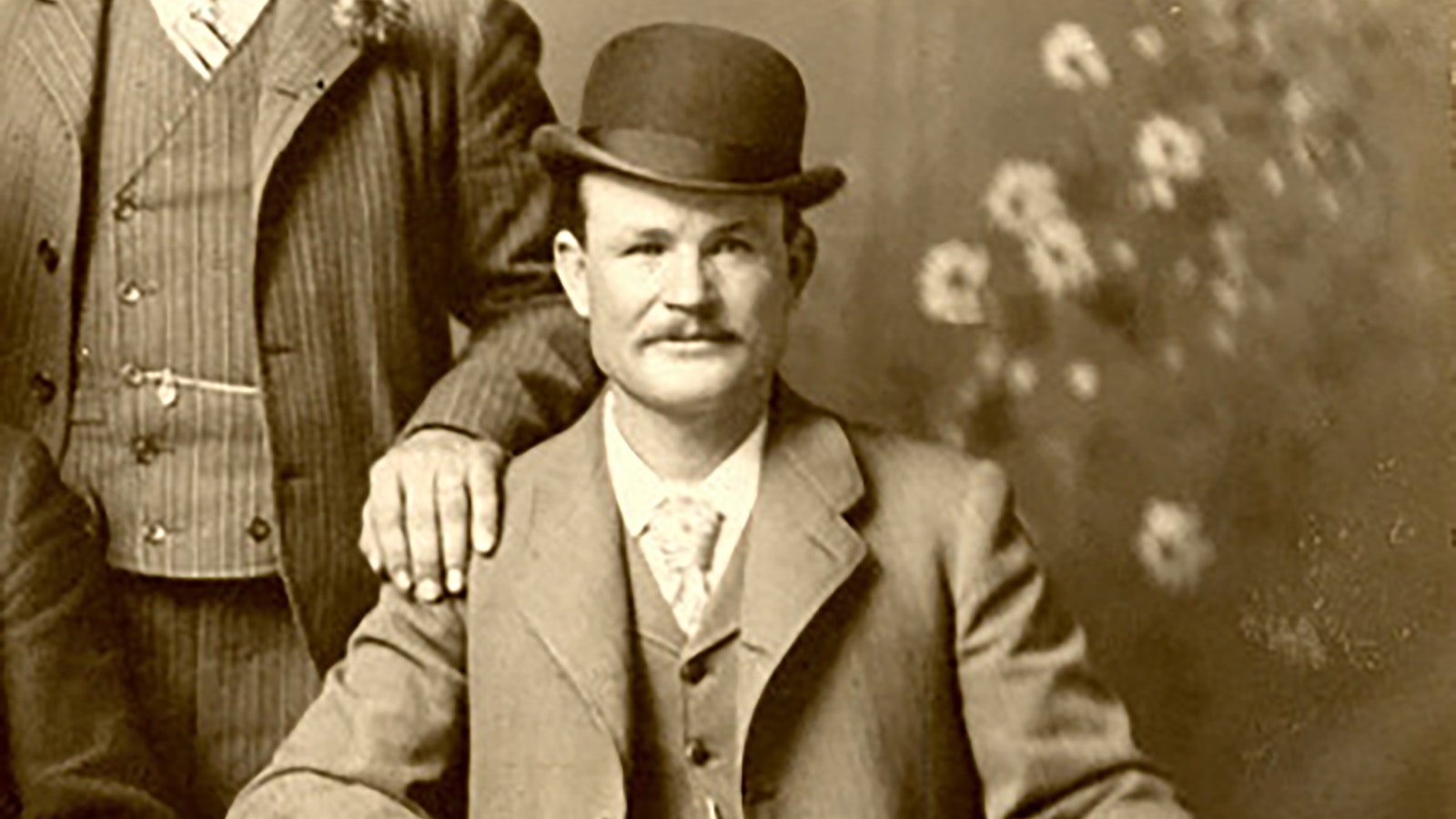

This is the first in a series about the famous outlaw Butch Cassidy and his connection to Wyoming. Up next is about Cassidy's best friend Matt Warner who started his life as a Western outlaw.

Roy Parker seemed to be having quite the string of luck.

The 23-year-old had just drawn his third queen in a game of all-day poker with his newfound friends and bank-robbing companions, Matt Warner and Tom McCarty.

But there was a tired look to young Parker as he eyed that third queen.

The man who would become Butch Cassidy, one of America’s most notorious cowboy outlaws, had been hiding out with Warner and McCarty in Charley Crouse’s cabin in Brown’s Hole, Wyoming, for a couple of days, fresh off the June 24, 1889, robbery of the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride, Colorado.

A lot of poker hands had passed through their sun-bronzed fingers by then, and they were all going just a little bit stir crazy. Like it or not, though, these men had nothing else they could safely do to pass the time.

Though the three had hauled $31,000 from the robbery — worth just over $1 million in today’s money — they couldn’t afford to spend this newly acquired bounty that had stirred up law enforcement in multiple states. Large rewards had been put up for their capture, and it seemed every which way they went, someone was looking for them.

“We had no idea how taking $31,000 from a bank would stir up the whole country against us,” Warner recalled in his memoir “The Last of the Bandit Riders.”

There was a “dragnet” waiting for them in “every state and county” of the West, he wrote.

Each man had carried a third of the heisted money with him as they fled from one hideout to another, chased along the way by the law. The money bags had worn a raw and painful ring around each man’s waist. Each had threatened to toss their money belt away more than once by this time.

But until just then, none had actually done so.

Parker, however, didn’t hesitate to toss the entire belt of money down on the strength of his three queens beating Warner’s three jacks.

Warner, however, drew a fourth jack and tossed his money belt in alongside Parker’s.

McCarty, with nothing good showing, kept his money belt and passed.

“Butch was game to lose all he had,” Warner recalled. “But I didn’t want his money. I told him I would shoot him if he tried to make me carry another dollar of the damn stuff.”

Warner knew that while his friend Parker might be tired of being on the run, he didn’t really want to give up everything he’d just risked his life to get.

And he was right. Butch was already tired of the outlaw lifestyle — even as it was just beginning for him with his first bank robbery — but he accepted the money bag back without a fight.

A Bet And A Friendship Are Made

It wasn’t the first time Warner had let Parker off the hook this way.

The first time was in Telluride some months ago, when the two had placed an alcohol-inspired bet one against the other on a horse named Betty and a horse Parker believed couldn’t be beat.

Neither man was in Telluride to rob banks. They wanted to make some fast cash, and a little betting on horse racing seemed like the surefire way to do it.

Betty was the fastest horse that Warner and McCarty had ever seen, and they figured to make a killing off her in Telluride, luring suckers in by underplaying the filly’s abilities. They never let her win by too big a margin in any given race.

This had set the stage for a matchup with the local favorite, owned by a man named Mulcahey. It was right after betting $500 to bind that race that Warner and Parker bumped into each other at a fancy saloon full of what they both described as “lady-fingered” men — men who’d never done any kind of manual labor — which both agreed didn’t really suit their taste.

Parker, like Warner, already had a great interest in racing horses. In fact, not so very long ago, using the name Ed Cassidy, he’d shown up in Brown’s Hole to successfully race a horse to victory for Charlie Crouse. The same Charlie Crouse who had sold Betty to McCarty and Warner. And the same Charlie Crouse whose cabin they would eventually land in, playing bored games of poker to try and pass the time.

Parker bought Warner a drink and told him it was an expensive mistake to bet against the Mulcahey horse. Warner bought the next round and suggested that Parker should put his money where his mouth was.

All Parker had to bet was his personal riding outfit. That was about all Warner had as well.

When Betty indeed won the race, he figured he’d never see Parker again. But Parker showed up with saddle, chaps, bridle and spurs and insisted Warner take them.

Warner wasn’t the type to leave a cowboy without his gear, but Parker said he wasn’t the kind to “squawk” about it when he lost.

So Warner found a clever way out for them both. He offered Parker a job matching up horse races for Betty all over Colorado.

When Parker accepted the job, he thrust all of Parker’s gear back at him.

“I won’t have a partner trailing me around race tracks afoot,” he declared firmly. “You’ll have to use these while you’re with me.”

Betty Runs Out Of Suckers

Horse racing was loads of fun for the three men, but word of Betty’s speed spread almost as quickly as the horse could run, and they soon ran out of people to sucker.

They also ran out of money about as fast as they made it. After every win, they would blow all their winnings on parties in the saloon. They needed a new gig, and only something lucrative would do.

These were not men who were interested in the plodding strategies of honest men. Parker, for one, had already seen how that played out for his own parents.

They had lost their family ranch in a property dispute, which forced them to move and start over again. They’d lived like paupers before that and were even poorer after.

So, it wasn’t difficult for Warner to convince Parker that a bank job in Telluride would be easy and set them up nicely.

It was their elder, McCarty, who needed convincing.

Big cities like Telluride are full of people packing pistols, McCarty pointed out, and none of their escapades to date had been in crowded cities. It wasn’t wise to try something with so many people around to fight back.

Let’s stick with open country,” he told them. “We can get rich here in a few years of safe operations.”

But McCarty and Parker weren’t interested in taking years of their life to get rich.

“Cowboys has been getting away with bank robberies lately in a number of Western states,” Warner said. “Can any range-riding maverick in the United States do anything we can’t do?”

Pride wouldn’t let McCarty answer that question any other way than a resounding no. The bank robbery was on.

Enough Cash To Choke A Cow

The outlaw trail is not a defined system of trails.

It’s a loosely connected series of hideouts that stretch from Texas to the Canadian border, connected by trails that exist still today in some of the most remote, rugged and dangerous places in America. Many of these areas, including Brown’s Hole, have become state and national parks since then and look much as they did in 1889.

Parker, Warner, and McCarty had not done anything yet that would firmly plant their footsteps on the Outlaw Trail. But that would all change with the Telluride Bank robbery.

The Rocky Mountain News out of Denver attributed the robbery to the “Stockton Gang,” and described the caper as “four daring cowboys” pulling off one of the “boldest affairs” of its kind “ever known in southern Colorado.”

According to the article, two of the four entered the bank after one of the cashiers left, while two remained on the street watching the horses and the entrance to the bank.

Inside the bank, one robber presented a check to the remaining clerk, grabbing him by the neck and shoving a gun in his face just as he bent to examine the check.

After that, according to Warner’s account in his memoir, Cassidy filled one sack with enough cash to “choke a cow,” then went into the vault to get some more.

The newspaper article says McCarty threatened to shoot the sobbing clerk for being such a big coward before they left the bank with what the paper said was close to $21,000.

Later newspaper articles would detail how the quick-thinking clerk had saved almost $6,000 in cash by quickly covering it with a newspaper.

McCarty, Parker and Warner rode out of Telluride with gunshots in the air, the newspaper article said, and it was at least 15 minutes after that before the other cashier, whose name was Painter, returned to the bank.

“It’s all gone, all gone,” the clerk told Painter.

Outlaws Try To Save The Sheriff

Warner, in his account of the robbery, does not mention who the fourth cowboy might have been. Various identities have been suggested over time, including one of Parker’s own brothers.

The fourth individual did not go with McCarty, Warner and Parker on their wild ride across the countryside. The three ultimately found posses coming at them from all different states and directions — all after the reward money that had been offered for their capture.

Eventually, they shook the posses off their trail and made it to Robber’s Roost in Utah, where they figured they’d finally be safe until things died down.

But things did not die down, not at all. And when Parker finally took a chance on more provisions for their dwindling supplies, he was spotted by an acquaintance in Green River, Utah. That put a stubborn bulldog of a man on their trail — a man Warner referred to only as Sheriff Fares. He had a reputation for always getting his man.

Unfortunately for Fares, he did not know Robber’s Roost nearly as well as Parker and his colleagues. McCarty, Warner, and Parker spotted Fares and his two deputies long before he spotted them.

At first, the three bank robbers were all for just shooting the lawmen.

But, when they saw the three lawmen heading the opposite direction from the only water source around, that no longer seemed sporting. They decided instead to help the lawmen survive this foray into Robber’s Roost, hoping it might also persuade the officers to let them go.

Ambush Awaits

McCarty took a position high up on a ridge, far from the officers but within eyeshot, and fired a shot to get their attention. As the lawmen made for his location, McCarty left a note that said essentially, “Water is this way. Follow me if you want to live.”

Even though the lawmen suspected an ambush, they were desperate for water. And, indeed, the outlaws were set up within earshot of the watering hole to listen in on what the lawmen were saying.

The bank robbers had decided if what they heard was favorable to them, they would just let the lawmen go. Otherwise …

After drinking their fill, two of the lawmen agreed that it had been mighty kind of the outlaws to take a chance and save their lives this way, and they were all for leaving the outlaws to Robber’s Roost and saying that they couldn’t find them.

But Fares had no intention of giving up. He had a reputation to maintain.

“This is all a trap anyway,” he insisted. “You wait and see.”

McCarty was so incensed by Fares’ attitude, he wanted to shoot all three men right where they sat. But that didn’t seem too sporting with such an obviously fatigued party. So instead, the three outlaws surrounded the three lawmen, covering them with their rifles.

To teach the sheriff a lesson, they forced him to remove his pants, then put him on a horse headed back into town with his partners right behind him. They pinned the pants to a tree with a note that said the sheriff might always get his man, but he didn’t always get his pants.

The sheriff, according to historical accounts, bore this humiliation with as much dignity as a man of his stature can muster, declining offers to bring him some pants before he rode into town, saying that he deserved this for letting “cheap outlaws” get the better of him.

Now that the law had found them at Robber’s Roost, the “cheap outlaws” realized they could no longer afford to stay. They needed a new hideout, and that is what ultimately sent them to Brown’s Hole, playing endless rounds of poker.

Outlaw’s Dream Hideout

Brown’s Hole is a place where three states meet in one place — a fact which was not lost on smart outlaws like McCarty, Warner, or Parker.

One day, Brown’s Hole would become the most important hideout for Parker — though its fame has long since been eclipsed by the red cliffs near Kaycee and Ten Sleep known as the Hole in the Wall.

Today, Brown’s Hole is a national wildlife refuge, full of adventures and world-class fishing, in an uncommonly beautiful valley. It is still one of the most remote places in the West, with lush green forage ringed by mountains that protect it from winter wind. The cattle here still roam the open range, too, much as they did when Cassidy was still roaming the earth.

Visitors to the park will even find the John Jarvie Historic Ranch, where Butch Cassidy once shopped. It has been restored and kept intact, much as it was in Cassidy’s day. There’s a general store open weekdays for visitors, along with a blacksmith shop and other services once offered by the ranch.

Jarvie’s initial homestead, a bunker built into the earth, still exists as well. It was kept for storage after Jarvie built his bride a nicer home, and it was used by many an outlaw to hide, possibly even Cassidy, according to park literature.

Jarvie even sold bootleg whiskey from his ranch — which got him in rare trouble with the law. Most of the time, though, the law stayed as far away from Brown’s Hole as it could, knowing it to be full of wild and lawless men.

In fact, any time bar patrons in Rock Springs, Green River or Vernal, Utah, would shoot up the place, it was inevitably blamed on that “wild bunch” from Brown’s Hole, which only helped to build the location’s reputation.

The inhabitants of Brown’s Hole always knew their neighbors had a past, just as they did.

It wasn’t customary in Brown’s Hole to ask anyone too many questions about their past. That made it the perfect hideout for outlaws like Cassidy, and it was a place he would return to, time and time again, throughout his Wyoming years.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.