SAVERY — It’s not walls that William Stocks of Dixon wishes could talk.

It’s swords.

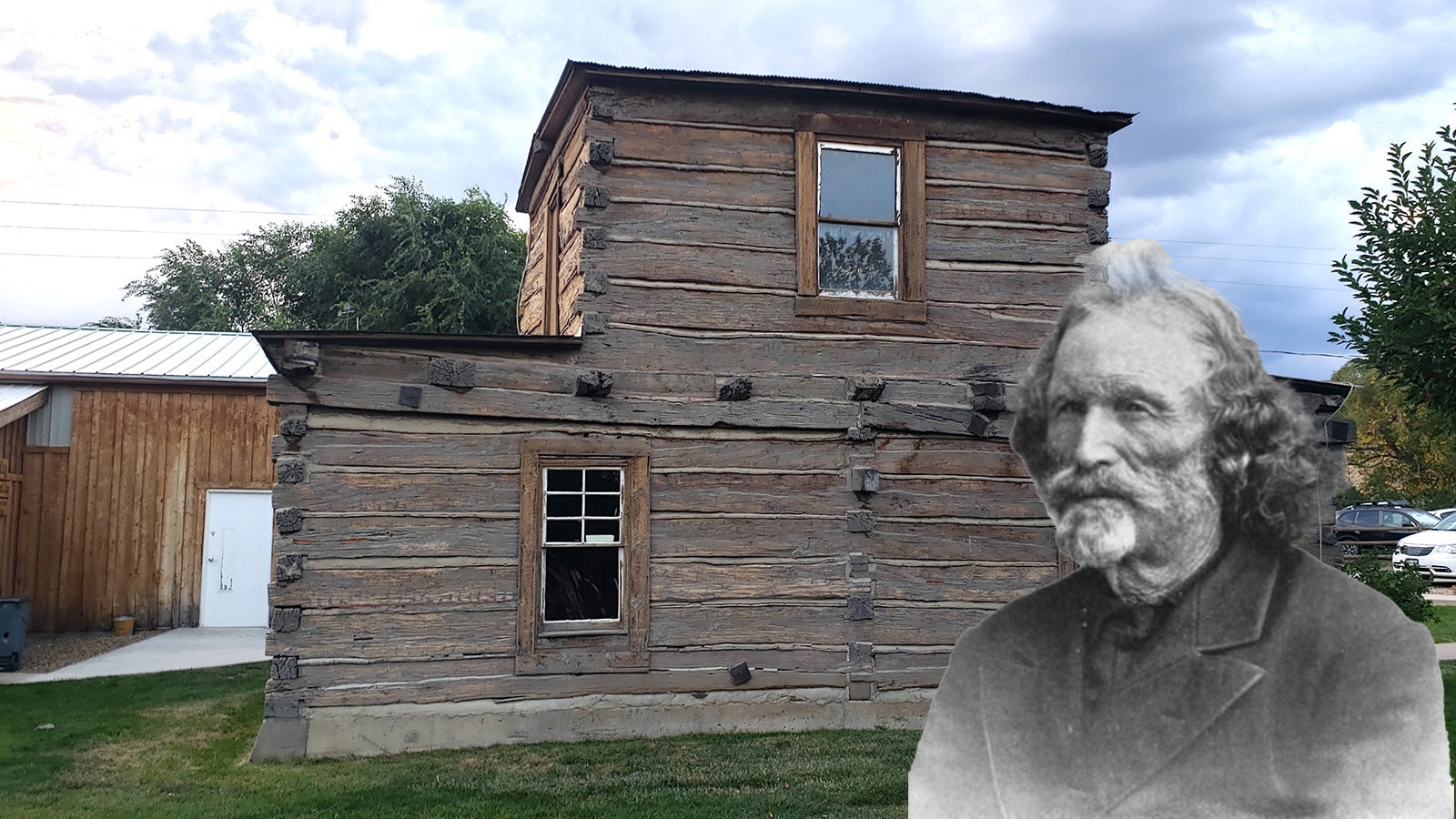

Specifically, a time-blackened sword that once belonged to Wyoming’s legendary mountain man Jim Baker. A sword that Stocks has just given to the Little Snake River Museum, where Baker’s original cabin still stands, and where Baker’s beloved 1869 Sharps rifle is on display.

Stocks, who made the donation Monday, June 17, said it was important to him that Baker’s sword find a home “where it belongs.” As he sees it, that is in Savery, where Baker came to live out the remainder of his days.

“Some say Baker is the forgotten mountain man,” Stocks said. “Not around here. When I look at, you know, past, present, and the future, Jim Baker deserves not to be forgotten.”

Baker doesn’t have the same fame as Hugh Glass, whose story was retold recently in the film “The Revenant.”

But Baker was no less legendary. One of the last of the mountain men, he was still making his living as a trapper long after the last official trapper rendezvous in 1840. Most of his colleagues gave up the dangerous profession soon after that rendezvous and moved on to other careers.

Baker is best known for the Battle Creek Fight. An old newspaper clipping found by Cowboy State Daily that features interviews with Baker and other contemporaries like Kit Carson, credits Baker with holding off an Indian force of hundreds with just two dozen trappers — Thermopylae-like odds.

Baker took the leadership role just after their commander was killed, using horses to serve as a barrier from gunfire, and husbanding their limited ammunition to make all-important kill shots, which kept their foes from charging and over-running them. He was just 22 at the time.

And Baker, like Glass, had survived bear attacks, two of the grizzly bear fights he himself instigated while traipsing around Wyoming with famous mountain man Jim Bridger.

His body was covered with scars from bear fights, and many historians believe those weren’t the only two bear fights he survived.

With stories like that, Baker was a larger-than-life figure to Stocks when he was growing up, and he was fascinated by the mountain man’s sword, which hung above the fireplace in Stocks’ childhood home. So much so, his siblings decided he should be the one to inherit the Baker sword.

Stocks, a history buff, never knew much about the sword growing up, other than how it came into the family’s possession.

That’s a tale that goes way back, before the founding of Dixon, Wyoming, in Little Snake River Valley, to the last days of Wyoming’s last mountain man.

Baker’s Old Stomping Grounds

Dixon today is the south-central gateway of the Medicine Bow Forest. It’s named after Bob Dixon, one of the region’s first white trappers, and a contemporary of Baker’s.

Baker was a frequent visitor, and still has descendants living in Dixon today.

Among the earliest Dixon residents were Stocks’ great-grandparents, Tennie C. Patton Jones and her husband Dayton C. Jones. They arrived in 1886.

At first, Dayton worked for a general store owner named Charles Perkins, located in present-day Baggs. After a falling out with Perkins, Dayton moved east, up the road, building his own blacksmith shop in what would eventually become Dixon.

He also partnered with W.T. Hays to establish a general store — Dixon’s first — and he served as the Little Snake River Valley undertaker for many years.

The “cold room” in the rear of Dayton’s blacksmith shop was not just used for undertaking, though, Stocks said. Teeth might be pulled by a visiting dentist, and minor surgeries like tonsillectomies were also performed there.

“Civic matters were ‘cussed and discussed’ in the front,” Stocks said. “As a blacksmith, D.C. was a very skilled maker and fitter of horseshoes. He was renowned for his ability to ‘customize’ them.”

Baker’s Last Days

The Joneses hosted an ailing Baker at Tennie’s boarding house just five years after they settled in the area.

“Baker was suffering from a kidney stone, and, I guess in those days, they just did these invasive surgeries,” Stocks told Cowboy State Daily. “Tennie, my great-grandmother, had a boarding house, and that is where Baker convalesced after the surgery.”

Not much is written about this period in Baker’s life, Stocks said.

Newspaper accounts of that era were more interested in exciting and lurid tales of grizzly bear fights and Indian battles. They had no ink to spill for a Wyoming mountain man’s illness.

Baker, known both as the Red-headed Shoshone and Honest Uncle Jim, depending on who you asked, would, in the mountain man vernacular of the day, “go under” quiet as a whisper. All the secrets of Baker’s sword would die with him.

Stocks doesn’t know for sure how long Baker stayed with his great-grandmother Tennie in her boarding house, or just what prompted him to give the sword to her.

His dad never talked much about the sword. He was more enamored of a rifle that he’d been given as a young man.

But Stocks believes the sword had a deeper meaning at one time.

“It was important enough and valuable enough to give it to Tennie C. for taking care of him,” Stocks said. “That’s all we know for sure.”

The sword comes with a small placard on which Tennie C. Jones swears the sword came to her from Jim Baker after he stayed at her boarding house in 1891.

The formality of the statement suggests Tennie knew the sword was an important artifact. She gave it to Stocks’ father on Dec. 8 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor was bombed.

“Whoever typed this card up spelled her name wrong, though,” Stocks said, pointing at what looks like a torn recipe card. “See, they spelled it like the state of Tennessee, but you can see when she signed it, she spelled it T-e-n-n-i-e.”

Unknown chain of custody

As a history buff, Stocks has done his own research on the sword itself. It came from a factory belonging to Nathan Starr Senior and his son, Nathan Jr., shipping out from their Connecticut factory in 1821. Starr was America’s first sword manufacturer and is well-known among history buffs and weapons collectors because he had so many military contracts, producing thousands of weapons.

In 1821, Baker would have been just 2 years old. Someone else had to have owned the sword first. Someone who was a soldier.

Who that soldier was is a mystery Stocks hasn’t been able to unravel.

“There were 10,000 of these swords,” Stocks said. “And they primarily went to state militias.”

After the war of 1812, the U.S. military realized that it was ill-prepared for conflicts, and it really didn’t have a sizable standing army. Its answer to that was the 1818 contract sword, destined to be carried by members of state militias, who could be called up for battle at need.

The swords were delivered between 1820 and 1822, and each was stamped with its shipping date.

The cavalry swords were marked with N. Starr U.S. and carried a proof mark, “P.” They also had the initial of the government inspector who verified the weapon for military use.

In the case of Baker’s sword, that was L.S., which stood for Luther Sage.

Sage inspected all but 1,000 of the swords. He would have been looking primarily at the quality of the sword, both the metal and the way the handle itself had been constructed.

The handle where the sword entered the hilt was often a particular weak point.

“A lot of swords would develop slack right there,” Stocks said, pointing at the base where metal sword and wood meet. “So, he would inspect all that just to make sure they fit the specifications of the contract.”

The first of the 1818 contract swords were delivered with leather scabbards, but those were later replaced with iron.

Baker’s sword no longer has its scabbard, or the belt used to strap it to a soldier’s body.

A Battle Weapon

In those days, the contract price for the 1818 Starr swords was $6, a sizable sum.

The swords are still valuable today as a highly sought after collector’s item. And they bring a good price, regardless of condition, because there aren’t too many of them left.

The Baker Sword is in great condition, tending to suggest it may not have seen the hard use that other swords in the series did. Its wooden handle is still intact, including the ribbed leather cover, and the leather washer at the hilt.

The latter is usually gone on most contract swords of the era, Stocks said. After all, these weren’t fantasy blades intended for ceremony. Men literally tried to strike killing blows with them, putting all their might behind their swings, which were, in turn, often blocked by equal and opposite force.

Many of the swords found use during the Civil War, as well as later, out on the frontier.

“There are no pictures of Baker with the sword,” Stocks said. “And we don’t know how he came by it.”

But Stocks’ gut feeling is that it must have come from someone in the military. Whether that was a general in the army — Baker sometimes served as a military scout — or a family or friend is not known.

“Maybe it came from his family in Illinois,” Stocks said. “Maybe he had someone who was in the militia give it to him when he got older himself. We just don’t know.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.