CASPER — Wyoming’s Wild West legacy has been built on larger-than-life stories that have inspired books, movies and a love affair with the Cowboy State’s outlaw reputation.

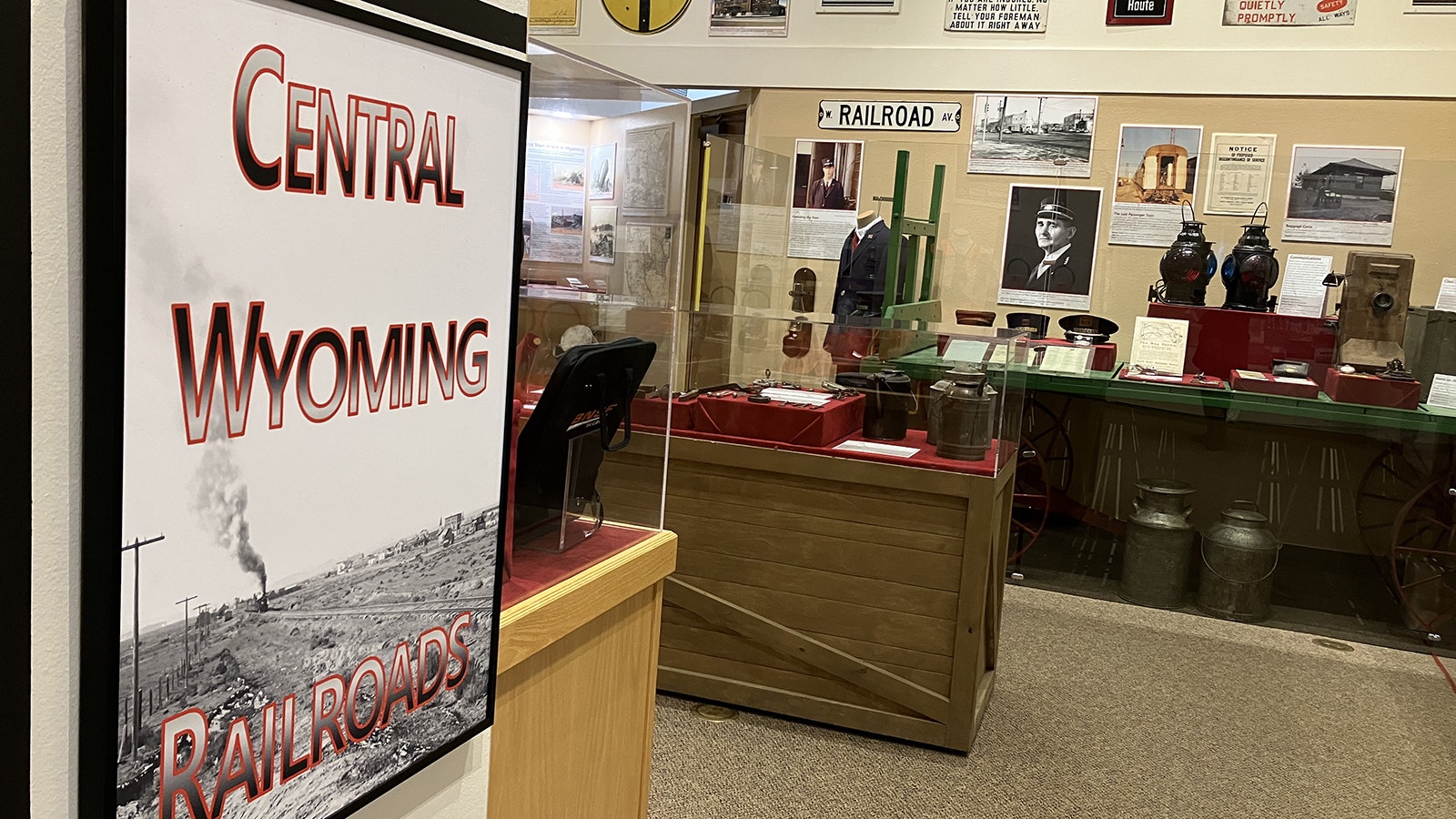

But it was the railroads that opened up Wyoming, spurred its growth and literally put it on the map between America’s coasts. It’s that history that’s inspired a Fort Caspar Museum exhibit highlighting the vital role railroads played in converting the region from an outpost to an economic hub.

“Central Wyoming Railroads” at the Fort Caspar Museum gives visitors a glimpse into the important role railroads played in converting the region from an outpost to and economic hub.

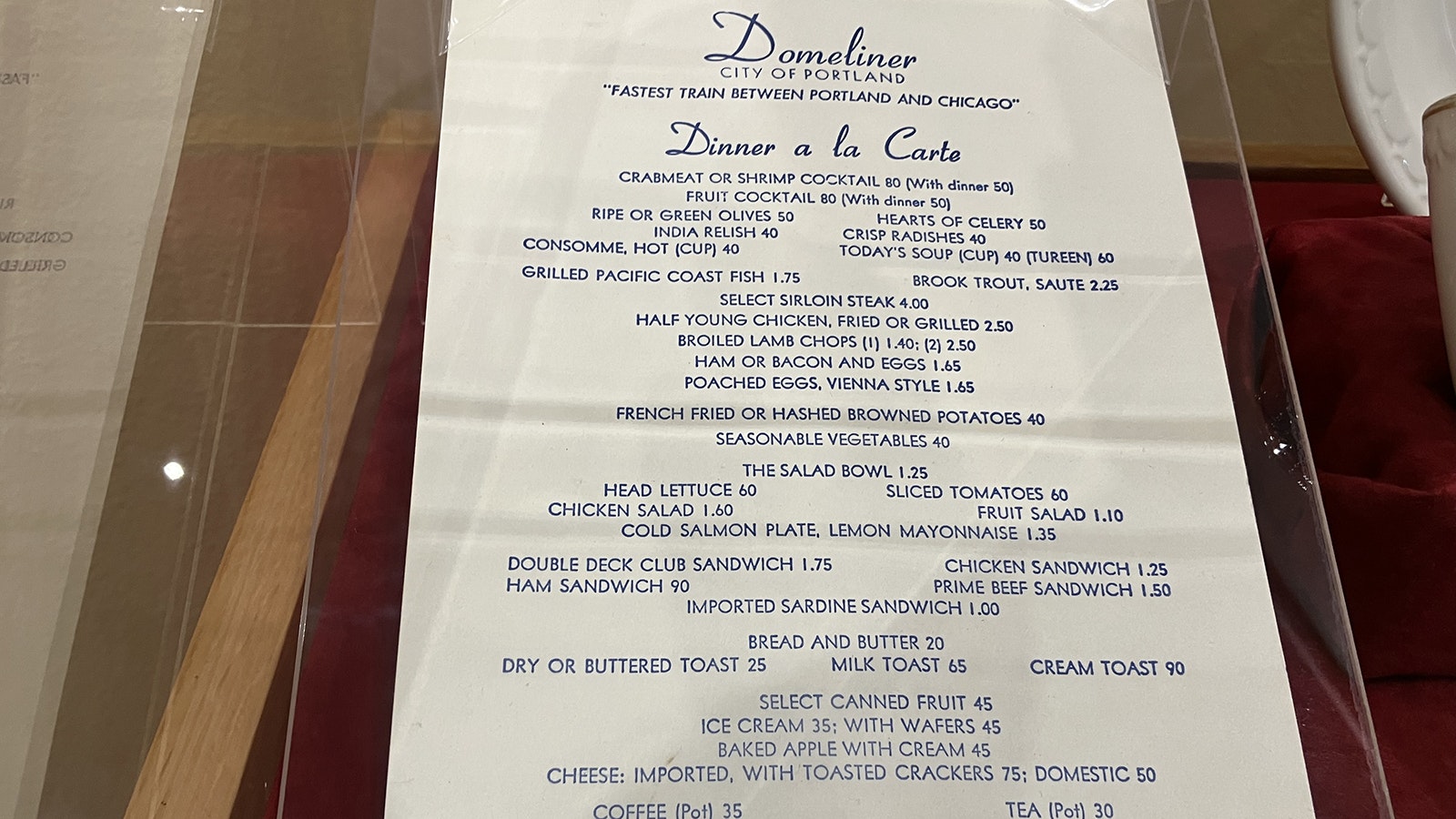

During its golden era, America’s railroads were the ultimate way to travel and represented luxury, status and money. It opened up the United States for commerce and were rolling hotels. The Pullman cars could be downright opulent while many trains featured chefs and fine dining better than people could find in many cities.

Museum Board Association Chairperson Con Trumbull, who works on a historic steam locomotive railroad in Nevada, said he helped pull together the “Central Wyoming Railroads” exhibit to showcase the impact railroads had in the region.

“When you look at Wyoming’s history, most all of our towns that we have today are tied to the development of the railroads, especially down along the UP (Union Pacific) corridor, that’s where that development started,” he said. “But even up here in central Wyoming, Casper did not grow until the railroad arrived.”

The railroads brought the supplies, people and goods over long distances, and when a railroad arrived it changed everything, Trumbull said.

Railroads Bring Change

“When the railroad arrives you see the fundamental change in the development of the town,” he said. “You very quickly go from small wooden structures with dirt streets to once the railroad arrives you start seeing the brick and the stone and the paved roads and the electricity. Everything really starts to boom.”

For example, in Casper during the 1920s there were more rail cars hauling oil to market than anywhere else in the world.

While the museum and other Casper entities do not have a lot of their own artifacts related to the railroads, Trumbull said the museum turned to some local railroad collectors to add to the display. The idea is to share the overall story.

“We tried to go by theme and show the different aspects of railroading both historically all the way up through modern operations,” he said.

So, visitors see brief histories of the major rail lines that impacted central Wyoming — the Chicago and Northwestern and Chicago, Burlington and Quincy. The exhibit also offers information on railroad signaling, the different roles and responsibilities of the railroad crew, and provides a sense of what was on the menu in those swanky dining cars.

There is also information on railroads themselves and some tangible links to the past including actual locomotive lights, lanterns, a baggage cart, and tools used by those who crewed the train, as well as other workers responsible for the tracks.

Conductor Uniform, Punch, Watch

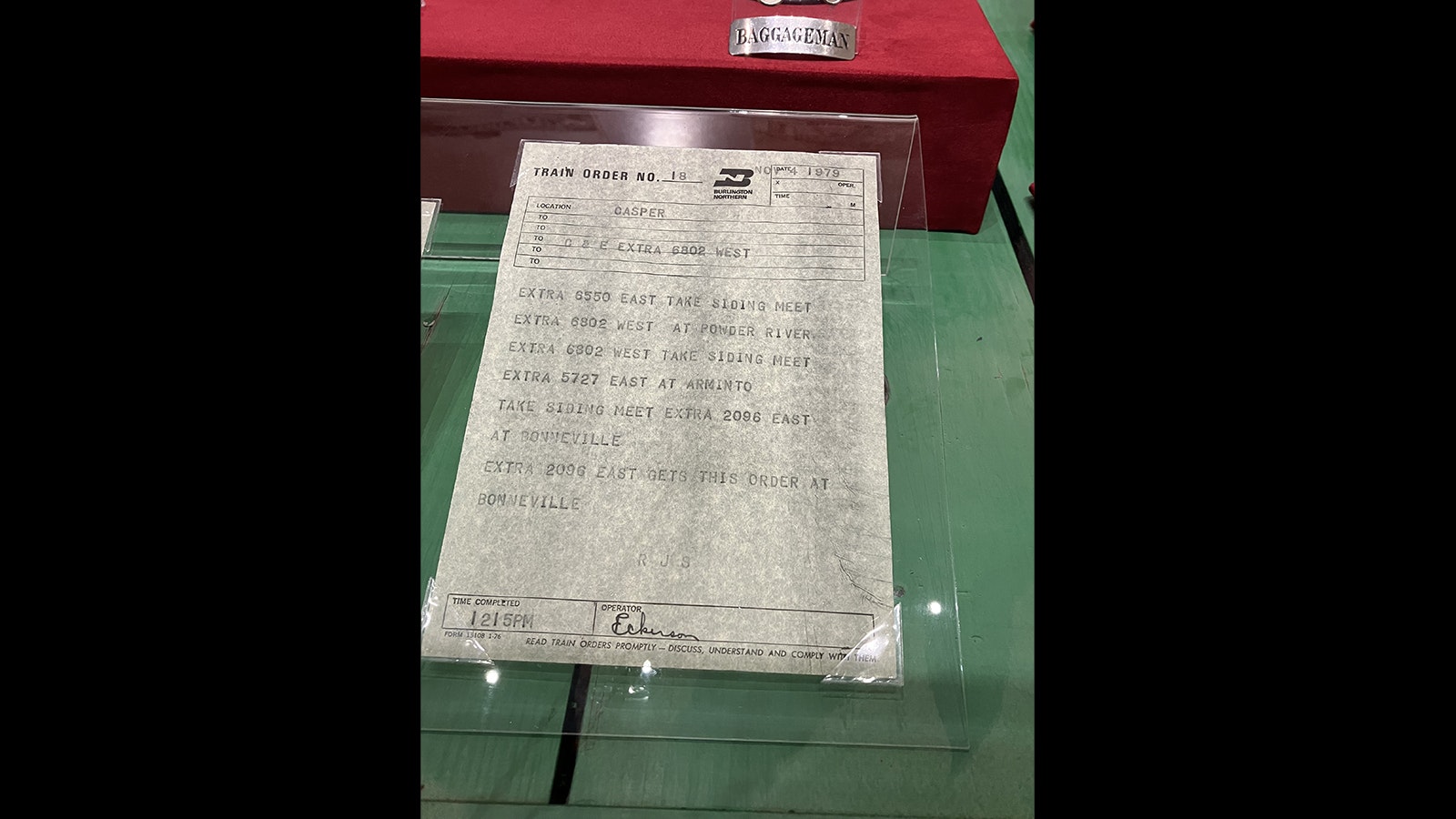

Trumbull said Casper resident Charles Eckerson, a former conductor and yardmaster with BNSF Railway, loaned his former conductor uniform and other artifacts to the museum.

“In the exhibit we have his original conductor’s uniform, we have lanterns that he’s got, tools that he used, pictures that he took and the stories of his time on the railroad,” Trumbull said.

Two marker lamps that Eckerson loaned to the museum were taken from the last passenger train to leave Casper in 1967.

There is also a conductor ticket punch. Each conductor had a ticket punch with their own distinctive shape. There is also a pocket watch and watch inspection card from 1949 that signifies how key time was to railroads, and railroads were to time.

“Railroads pretty much invented time for us in modern society. Time zones were a railroad invention,” Trumbull said. “Before you had radios and cellphones and computers, you had to dispatch trains, and the only way you could do that was by time. So, if you were a train, I’m going to say you can occupy the main line at 10:30 a.m. and you have to be off it by 11:30 a.m. And then I am going to send the next train.”

So, the railroads worked to ensure that all employees operated on a strict time schedule that was dictated by time zones with cities on the same time and then watches that had to be very accurate. Railroad employees had to have their watches, such as the one on display at the museum, inspected regularly.

“If they (the railroad) found that your watch hadn’t been inspected, that was grounds for pretty severe disciplinary action,” he said.

Cole Creek Train Wreck

The exhibit also has a small display on the worst train wreck in Wyoming history at Cole Creek on the evening of Sept. 27, 1923.

Rainfall in the region created a surge of water that took out the bridge over the creek between Casper and Glenrock. The bridge had been inspected a short time before the train left Casper. The locomotive and five of the seven cars plunged into the creek. In all, seven of the crew and 21 passengers died.

Trumbull, who has written a book on the wreck, said the display features an actual letter that has a postmark stamped 7 p.m. Sept. 27, 1923, and addressed by typewriter to “Standard Oil Co (Ind), Decatur, Illinois.”

“They recovered it from the wreck, they dried it out, they stamped it that it was salvaged from the wreck, and they sent it back to the oil company,” he said. “On the back side of that envelope there is still sand from the stream bed in Cole Creek. You can see on the front the discoloration from the sand but when you turn it over there is actually little pieces of sand on it.”

Museum visitors who stop by the display can also see a hat box on top of a trunk and piece of luggage on a baggage cart as it may have looked a century or more ago. The hat box was used by Wyoming Gov. B.B. Brooks, Trumbull’s great-great-grandfather.

“He was very much a train traveler. He went many times to Washington, D.C., and to Chicago,” Trumbull said. The hat box would have been for one of the governor’s top hats, “his dress up and go-to-the-White House hat.”

The exhibit offers a sense of the various roles and jobs on the railroad, the tools that were used, how modern railroad equipment compares to the past.

And while most travel is by car and plane today, the railroad used to be considered the ultimate way to travel in Pullman cars — a hotel on rails — and chefs serving up high class meals in a dining car.

Trumbull said Casper had Pullman cars that provided sleeping accommodations with a separate staff from the train crew. While Casper offered a diner inside its train depot, the region did not get the high-class dining that was available on the Union Pacific line.

A menu on display from the city of Portland Domeliner train that ran between Portland and Chicago offered travelers brook trout for $2.25, half a young chicken (grilled or fried) for $2.50, or broiled lamb chops for $2.50.

“There was a time in American railroading when you could almost get a finer meal on a dining car than you could in a restaurant,” Trumbull said. “It was a huge deal to eat on the train.”

Contact Dale Killingbeck at dale@cowboystatedaily.com

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.