Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 wasn’t a good thing for the ammonia industry — especially when a key pipeline carrying the commodity got shelled last June.

Global ammonia prices initially shot up on news of the invasion two years ago, then spiked again on the pipeline explosion, combined moves that hurt the fertilizer market that relies on the key ingredient in the agricultural-rich Ukraine region.

Halfway around the world, Wyoming’s energy industry paid attention to this pricing gyration.

The price of ammonia hit a high of $1,808 per metric ton in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — essentially doubling the average price of $904 per metric ton the prior year, according to data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

For followers of coal in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin and elsewhere, the ebbs and flows of ammonia prices may become a new economic barometer to watch for coal’s rebound. That’s because ammonia can be made from coal.

One Wyoming project sees opportunity in this trend — plus a way to establish an industrial base that disrupts the top export rankings of China and Russia.

The backers of a proposed project in the energy boomtown of Kemmerer in southwestern Wyoming fortuitously began penciling out its coal-to-ammonia factory in 2021, a year before the Russia invasion of Ukraine.

Folks there see the urgency now for pursuing their strategy as the world rapidly turns to ammonia to cut down on carbon dioxide pollution at coal-fired power plants and for making up for fertilizer shortages in the United States and elsewhere.

The joint venture backers — which includes Glenrock Energy LLC of Casper and Kanata America Inc., a Cheyenne-based unit of Kanata Clean Power & Climate Technologies Corp. of Canada — have proposed building a $2.5 billion factory in Kemmerer to turn coal into ammonia, Matthew Coeny, Glenrock’s managing director and chief financial officer, told Cowboy State Daily.

Coal Is Unique

The process is unique because most energy-to-ammonia projects are done with natural gas, not coal, he said.

The joint venture’s proposed project, called the Kemmerer Decarbonization Works (KDW), would be built adjacent to the Kemmerer Coal Mine, which last year produced nearly 2.5 million tons of coal, according to data provided by the Wyoming State Geological Survey.

The Kemmerer mine supplies coal to the two-unit Naughton coal-fired power plant, which is a 15-minute drive through Kemmerer to the southwest of the mine.

Rocky Mountain Power, the Wyoming electric utility owned by the Berkshire Hathaway-backed PacifiCorp, has indicated plans to convert the coal units to natural gas in 2026, and to eventually retire Naughton a decade later.

Coeny, a former institutional private banker on Wall Street with Citibank who worked energy deals, said that his company is in talks with potential strategic and financial partners, and possibly customers, to make the plant a reality.

These customers could include overseas buyers of ammonia produced in Kemmerer in Japan or South Korea, like JERA, which is the combined power departments of Tokyo Electric Power Co. and Chubu Electric Power Co., or South Korea’s Energy Ministry.

In the case of JERA, the power company has ambitious plans to transition its existing thermal power plants to 100% ammonia combustion by 2050.

And South Korea’s Energy Ministry projects over half of the country’s coal-fired power plants will be running with ammonia by 2030.

Opportunity

Coeny also sees possible buyers of its ammonia in the upper Rocky Mountain region and Wyoming.

He cited farmers who need ammonia for fertilizer used in growing hay and alfalfa, or even a specific customer such as Cheyenne’s Dyno Nobel factory that requires the commodity for manufacturing fertilizer and ammonium nitrate, a chemical used in explosives in Wyoming coal mines.

His company estimates an ammonia supply deficit of as much as 500,000 metric tons per year exists within 300 miles of Kemmerer. Demand for ammonia from industrial facilities exceeds supplies, he said.

“As a result, KDW could serve those customers with a lower delivery cost — and lower the carbon intensity of their products,” he said.

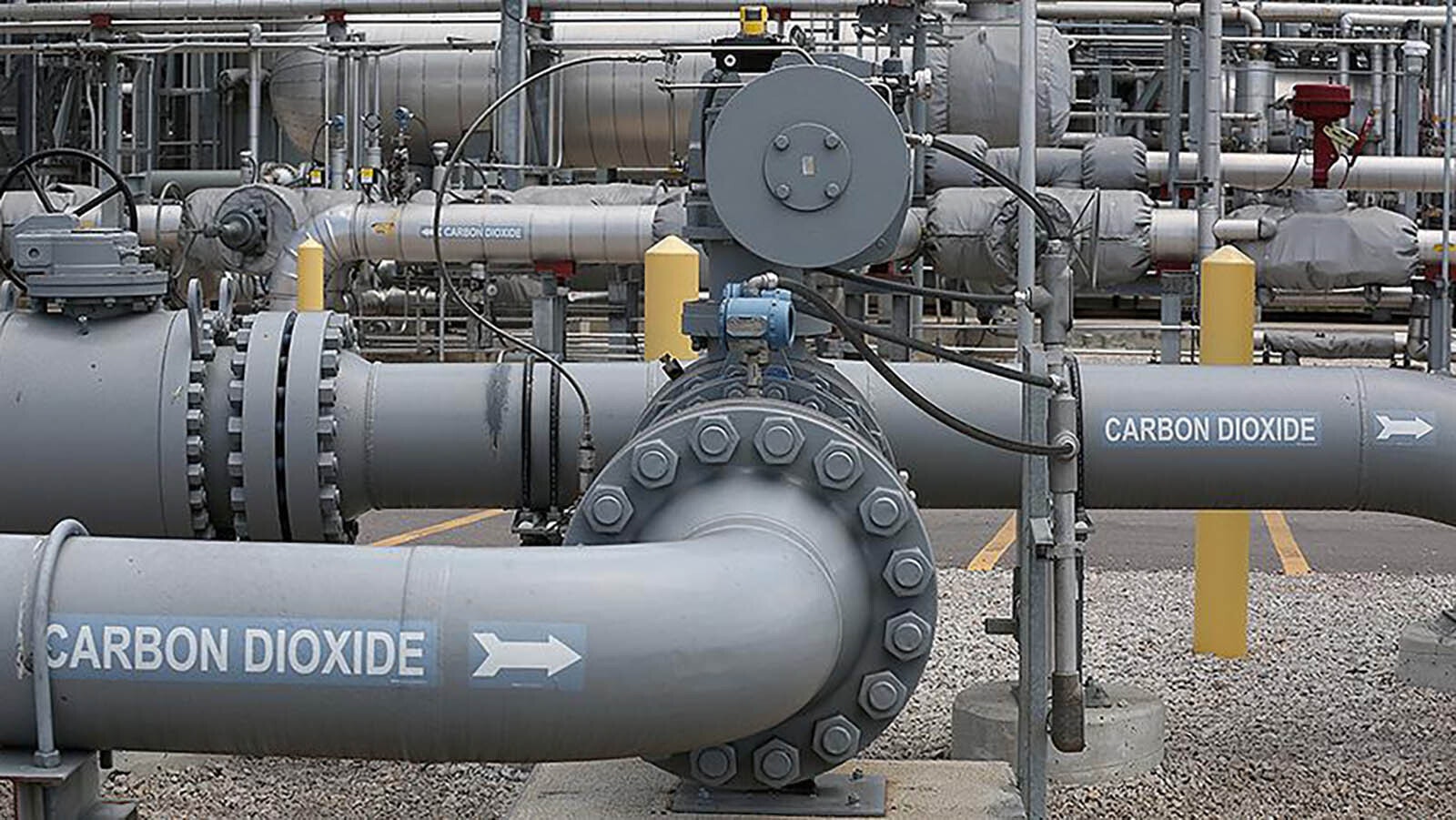

KDW’s project proposes a complex process to turn coal into ammonia that has been around for more than a century.

To make it all work, KDW said it needs a steady supply of roughly 1.5 million to 1.8 million tons of coal annually to strip out roughly 90% of the carbon dioxide and place it in storage.

In turning coal into ammonia, KDW would first break down the coal into a synthesis gas. That gas would then be used to generate electricity, with carbon dioxide stripped out along the way to produce ammonia.

All potential carbon emissions would be captured and permanently stored underground as part of the process.

The ammonia, said Coeny, could be transported to available regional markets on existing rail lines, or to ports along the West Coast or elsewhere for export destinations.

Coeny envisions a three-year construction process that could begin as early as late 2025.

The timing of the KDW project could coincide with Naughton converting to natural gas, meaning that KDW could take up the slack in coal that had gone to Naughton.

Even though KDW is envisioned for construction at the Kemmerer mine site, Coeny said that coal supplies could come from elsewhere.

Template For Future

"We are looking at multiple potential sources of which Kemmerer is one,” he said. “Our plan is to repurpose Wyoming coal.”

Coeny sees a national security purpose for the project as KDW is the only one of 32 existing ammonia plants in the United States that would rely on the coal-to-ammonia conversion process as others take natural gas to manufacture ammonia.

“We are the only one who plans to use coal,” he said.

The project sponsors also are considering the Kemmerer model as a possible template to build other coal-to-ammonia factories elsewhere in the United States.

“This plant is all about repurposing coal and utilizing technology that has been around for years,” Coeny said. “This could be the first plant, but it is very possible other states will want to use Wyoming coal.”

While Kemmerer might become the launching pad for the project, other sites are certainly possible in the Cowboy State.

“We could replicate this model elsewhere in Wyoming,” Coeny said. “Once this is up and commercially viable, there may be more interest.”

Pat Maio can be reached at pat@cowboystatedaily.com.