The first famous frozen dead guy in the world was not Bredo Morstol, patron saint of Colorado’s Frozen Dead Guy Days celebration held every year just south of Cheyenne in Estes Park.

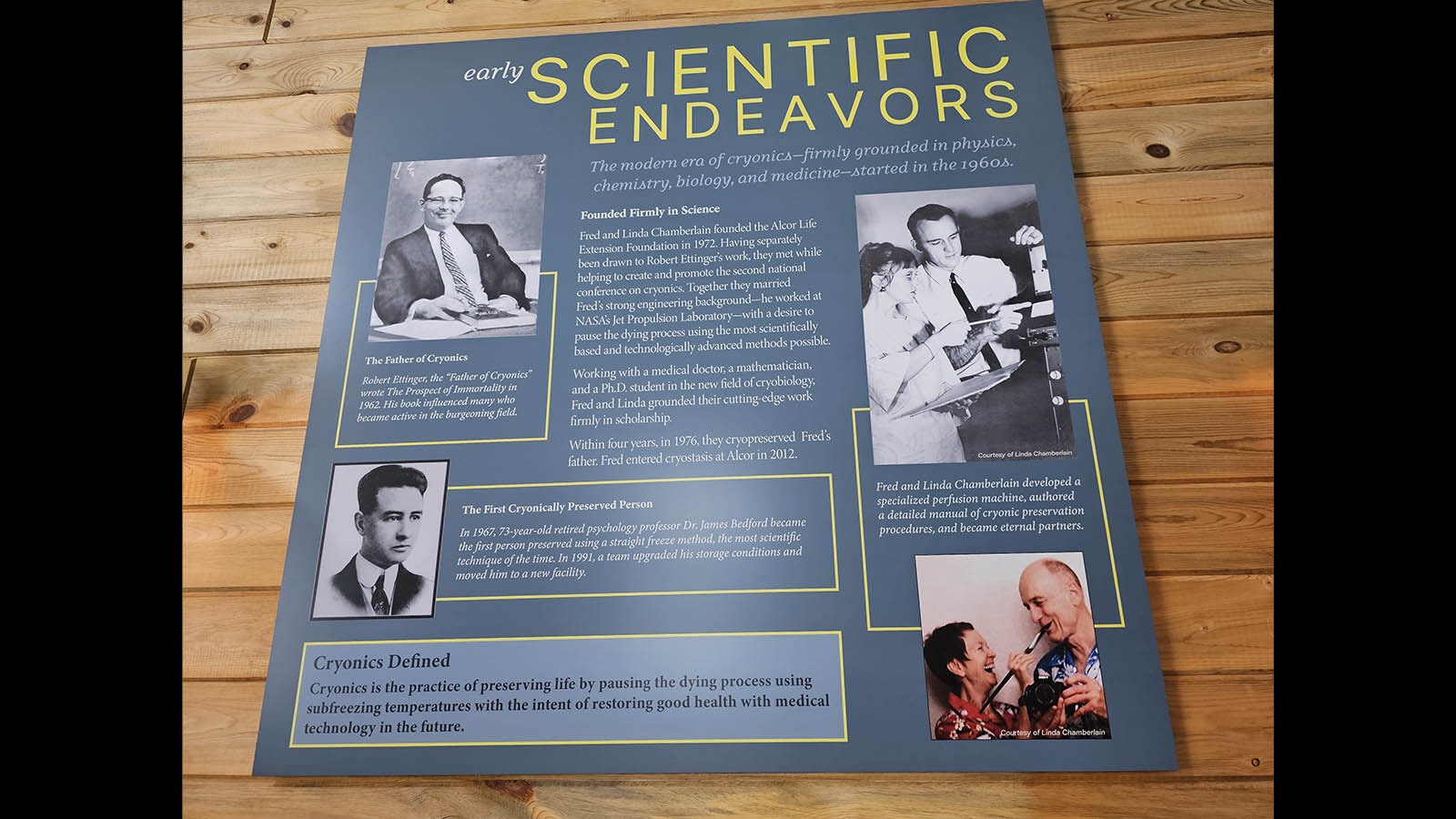

Morstol was cryonically preserved in 1989, after he died of a heart attack. But that was a long, long time after the first famous frozen dead guy, James Hiram Bedford, who died in 1967 of liver cancer after it spread to his lungs.

Although separated by more than two decades, Bedford does have a couple of things in common with Morstol.

Both men sparked media frenzies when their frozen state was discovered by the world at large, and both spent a few years at the Trans Time cryonics facility in Oakland, California — though not necessarily at the same time.

Today, the two frozen dead guys have come together under the same umbrella of care.

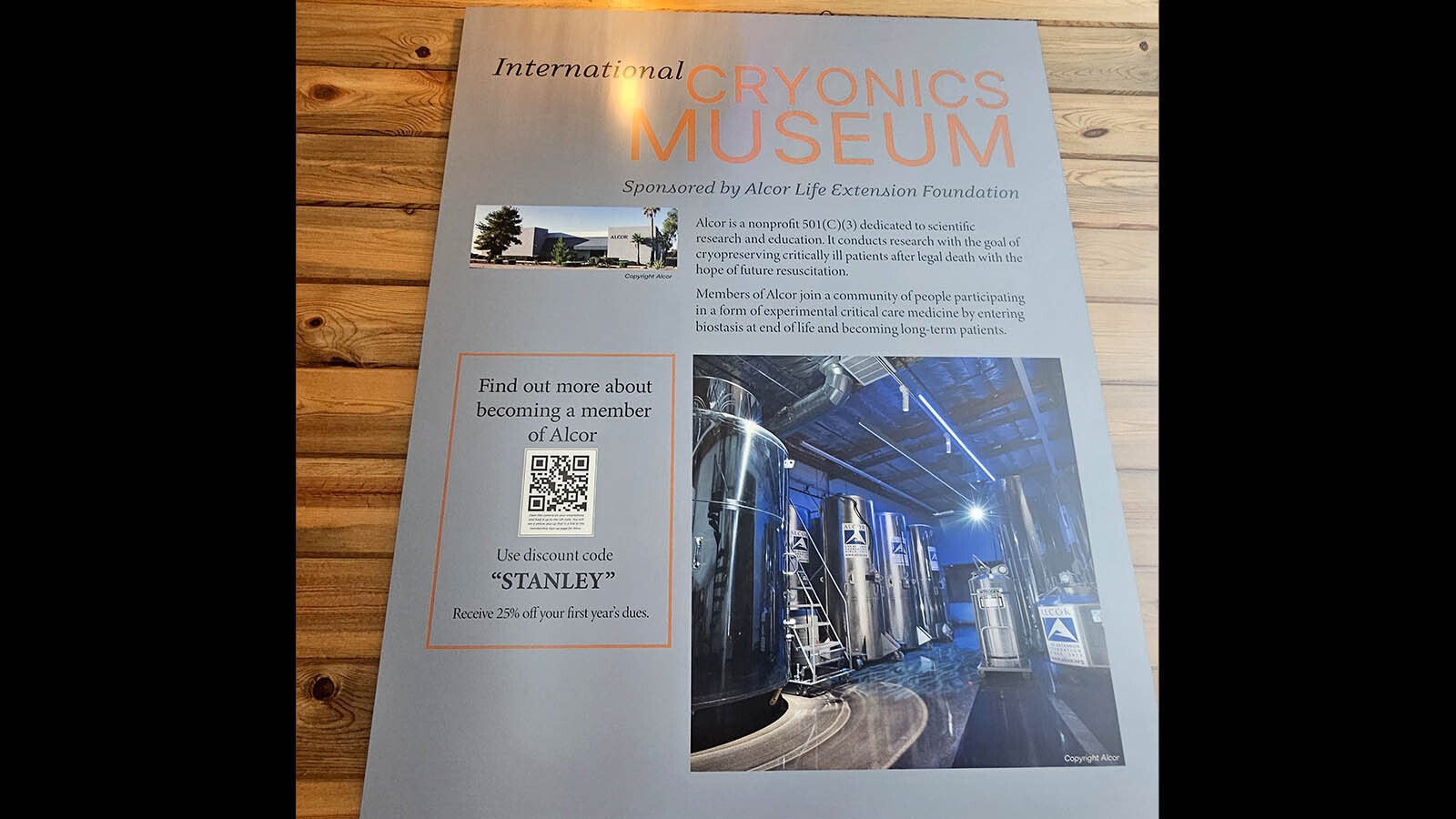

Bedford landed at Alcor Life Extension Foundation’s Scottsdale, Arizona, facility about 15 years after he was frozen, while Morstol this year became Alcor’s sole remote patient, residing in the world’s first International Cryonics Museum.

That was set up this year at the famous Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, an hour or so south of Wyoming’s border.

The two men also have one other thing in common — cryonic preservation wasn’t as advanced as it is today.

From Science Fiction To Science

Cryonics, which refers to preserving people who have died by freezing them, is a science that has been growing quietly over the past 57 years.

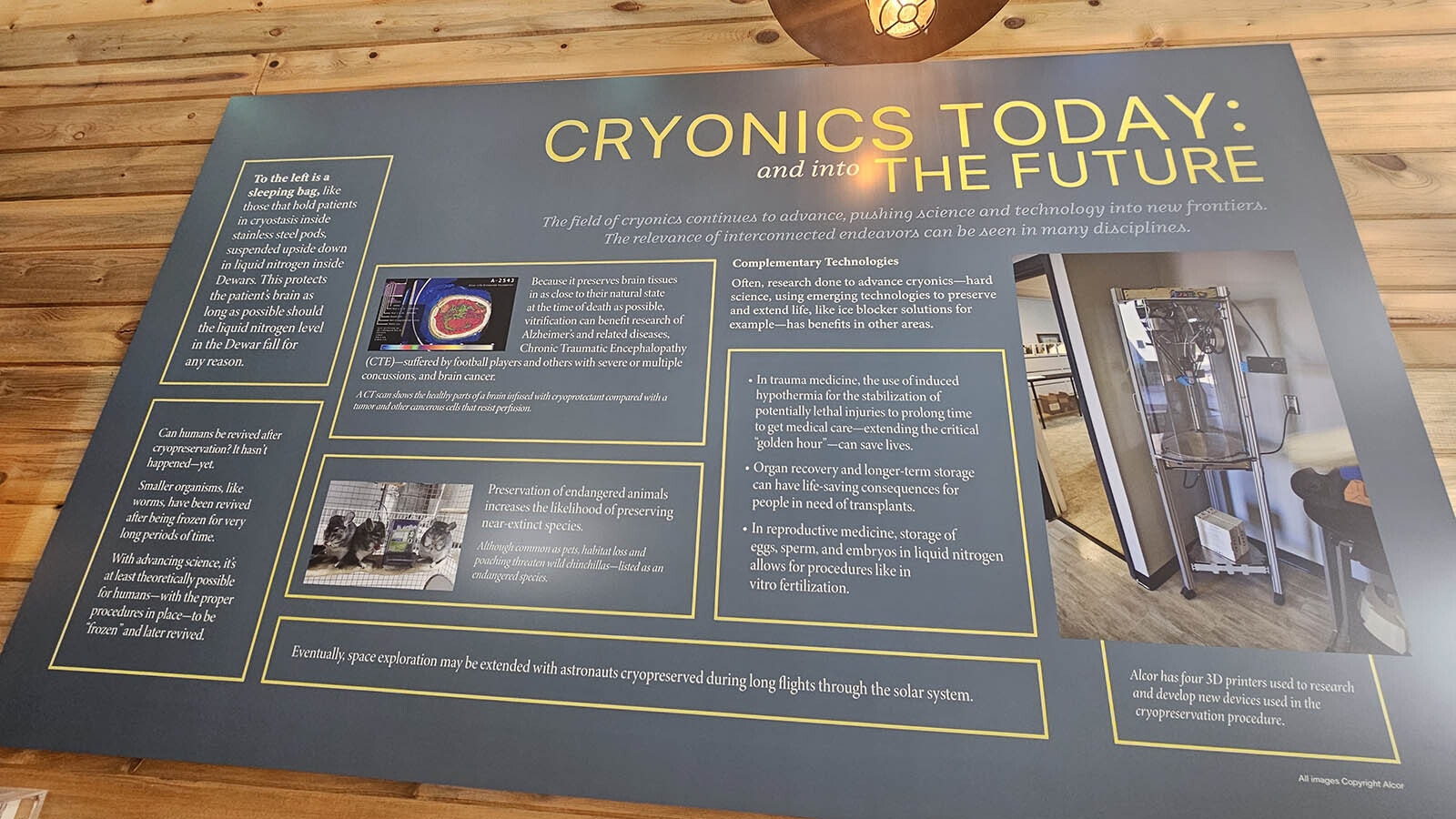

And while the past almost six decades may not have brought humanity any closer to reviving frozen dead people, the science has nonetheless progressed in hopeful ways.

Cryogenics — which refers to freezing things in general — and cloning have been used, for example, to help save Wyoming’s black-footed ferrets.

Rat kidneys have been successfully cryonically preserved for 100 days before thawing and transplanting into other rats.

Alcor’s Co-CEO and General Counsel James Arrowood told Cowboy State Daily that the nonprofit research center is focusing on attainable goals like kidney preservation and saving extinct species. These are meaningful baby steps along the way to a greater, aspirational goal.

“Kidneys are frankly one of the better organs to try to achieve in the near term,” Arrowood said. “And it’s also the one that could save a lot of lives right now, if we get it done.”

It’s also research that Arrowood believes would be difficult to do, except under a nonprofit model.

“It’s illegal to buy or sell a viable transplant kidney,” he said. “The government doesn’t want there to be a black market for organs, which makes total sense.

“But the problem is, how do you research whether a viable organ can be preserved unless you have viable organs to work with? And that’s where Alcor comes in.”

Freezing People Isn’t Easy After All

Water is a huge problem for cryonic preservation. When it freezes it expands, crushing the biological tissues that make up internal organs. Think about what happens to poor frozen strawberries once thawed.

With the human body made up of about 60% water, that’s a dynamic cryonics has to solve before it can ever hope to become an “ambulance to the future” that saves the life of a person who medical science couldn’t save at the time.

In Bedford’s time, there wasn’t yet any sort of state-of-the-art solution for the water problem. And, too, Bedford died earlier than expected, which led to more than a bit of improvisation for the world’s first cryonically preserved human.

The team that preserved him was an ad hoc mixture of people — a physicist, a chemist and a television repairman. They used artificial respiration to keep oxygen flowing to Bedford’s brain while they worked.

They then pumped a chemical called dimethyl sulfide into Bedford’s veins to replace his blood — trying to save his organs from freezing damage.

Today’s cryonic preservation has much better options, however.

The state-of-the-art now is a fish protein called M22. It’s isolated from the bodies of some arctic insects, as well as certain fish, amphibians and reptiles that are able to withstand freezing cold temperatures without dying.

“Think of it as biological antifreeze,” Arrowood told Cowboy State Daily. “You know, when you put antifreeze in your car, that’s to let the fluids continue to flow, even though it’s beyond freezing temperature outside, right? That’s the same idea in the body, to infuse or perfuse the body with something that replaces the water.”

The chemical is extraordinarily expensive, Arrowood added.

“And, because we are nonprofit, we don’t make any money on that chemical,” he said. “It’s an experimental chemical, and it’s just pretty much used for our type of research.”

Bedford was in many ways lucky to make it to Alcor at all.

Cryonics organizations of the time didn’t reckon with the uninterrupted long-term maintenance that a frozen dead body would require. That has even inspired a screenplay titled “Freezing People is Easy.”

But freezing a dead person is anything but easy, and making sure they stay that way is just as difficult.

In fact, there were 20 or so people cryonically frozen in the early days of cryonics after Bedford. Today, Bedford and two others are the only ones who remain frozen.

An Expensive Hail Mary

Alcor’s price tag isn’t cheap, but it takes both long-term maintenance fees into account, as well as doing research to keep advancing the science along.

Alcor’s present fees are $220,000 for whole-body preservation, or $90,000 for just the brain.

So why just the brain?

The idea is that the memories and experiences of a person will eventually be saved, whether through robotics or cloning or some as yet unforeseen method.

The fee is not as unattainable as it might at first sound.

“Most people pay the fee through their life insurance policy,” Arrowood said. “Like very few people write a check. I can’t afford it myself, and I’m the CEO. I’m the co-CEO, and I don’t get it for free.”

The $220,000 or $90,000 fee is essentially split three ways. One part covers the cryopreservation itself. One part goes to research to advance the science. And a third part goes to a nonprofit trust that is responsible for long-term maintenance if anything ever happens to shut down the lab.

“So, if the research lab were to shut down, there’s this separate nonprofit that has a bunch of money that can pay for a caretaker for the facility until somebody takes up the research again, or takes it up separately,” Arrowood said. “And Alcor cannot touch that money. It has its own board, it has its own governance.”

The research funding model has, from the start, always been a little bit like crowdfunding, long before that became an Internet buzz word.

“A bunch of people put in a little bit of money to accomplish a big goal,” Arrowood said. “And the way that happens is somebody like myself, you know I’m a member, a cryopreservation member, so you can be an associate member where you are just interested in the science and you get a newsletter, or you can be a cryopreservation member where you say, ‘Hey, I’m donating my body under the Anatomical Gift Act, essentially.”

Billionaires Are Buying In

It was just last year that billionaire Peter Thiel talked about his own plans to be cryonically preserved by Alcor after he dies, even though he’s skeptical that the technology actually works.

Headlines around the conversation suggested it was a shocking new development, but in reality Thiel has been talking about this idea since at least 2014, when he told The Telegraph that he didn’t see it as such a crazy thing.

“There’s always this reaction that it’s really crazy, it’s disturbing,” he said. “But my take on it is, it’s only disturbing because it challenges our complacency.”

In Thiel’s opinion, this is science humanity as a whole needs to advance. And he’s not the only influential person to think that way.

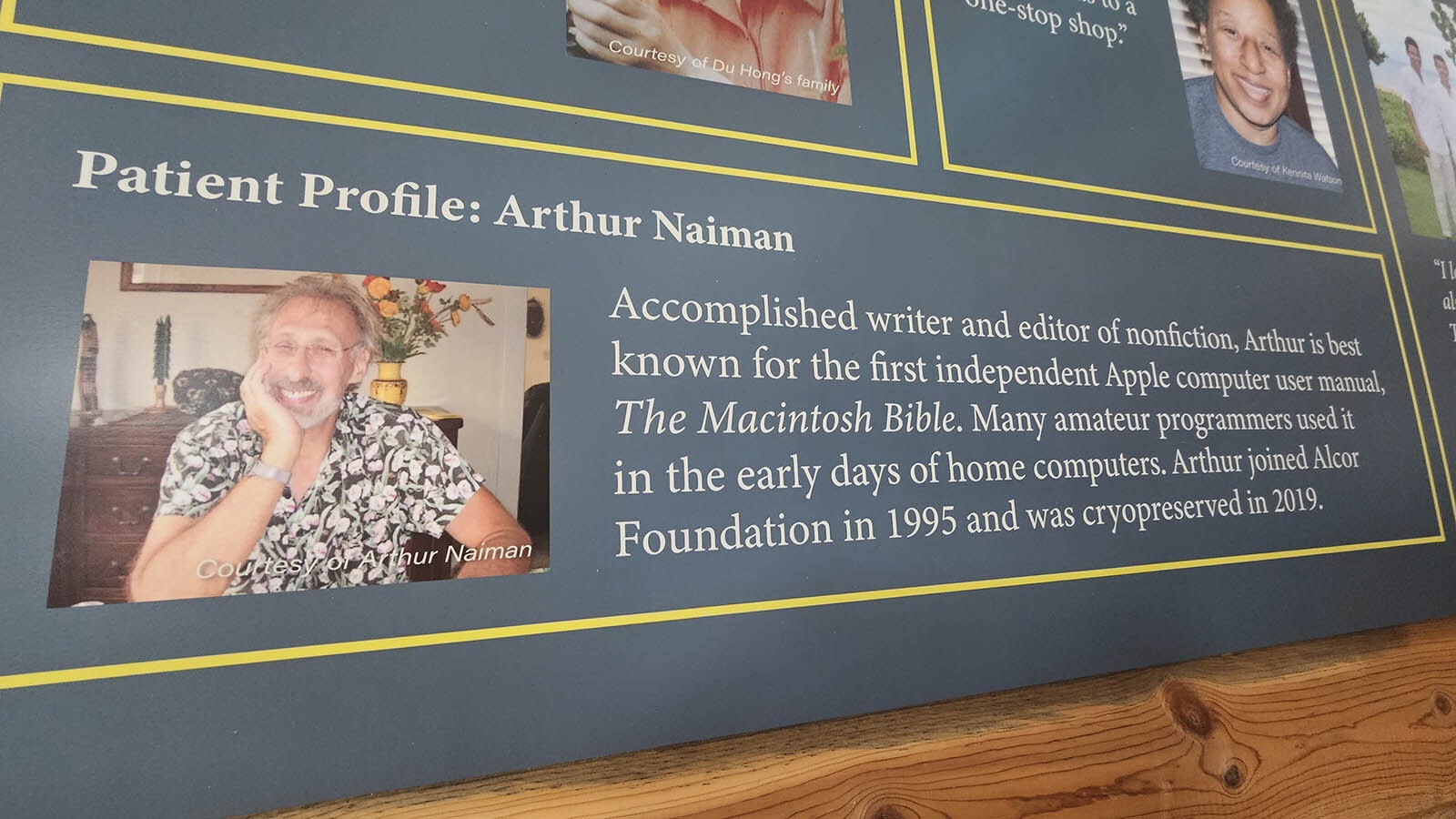

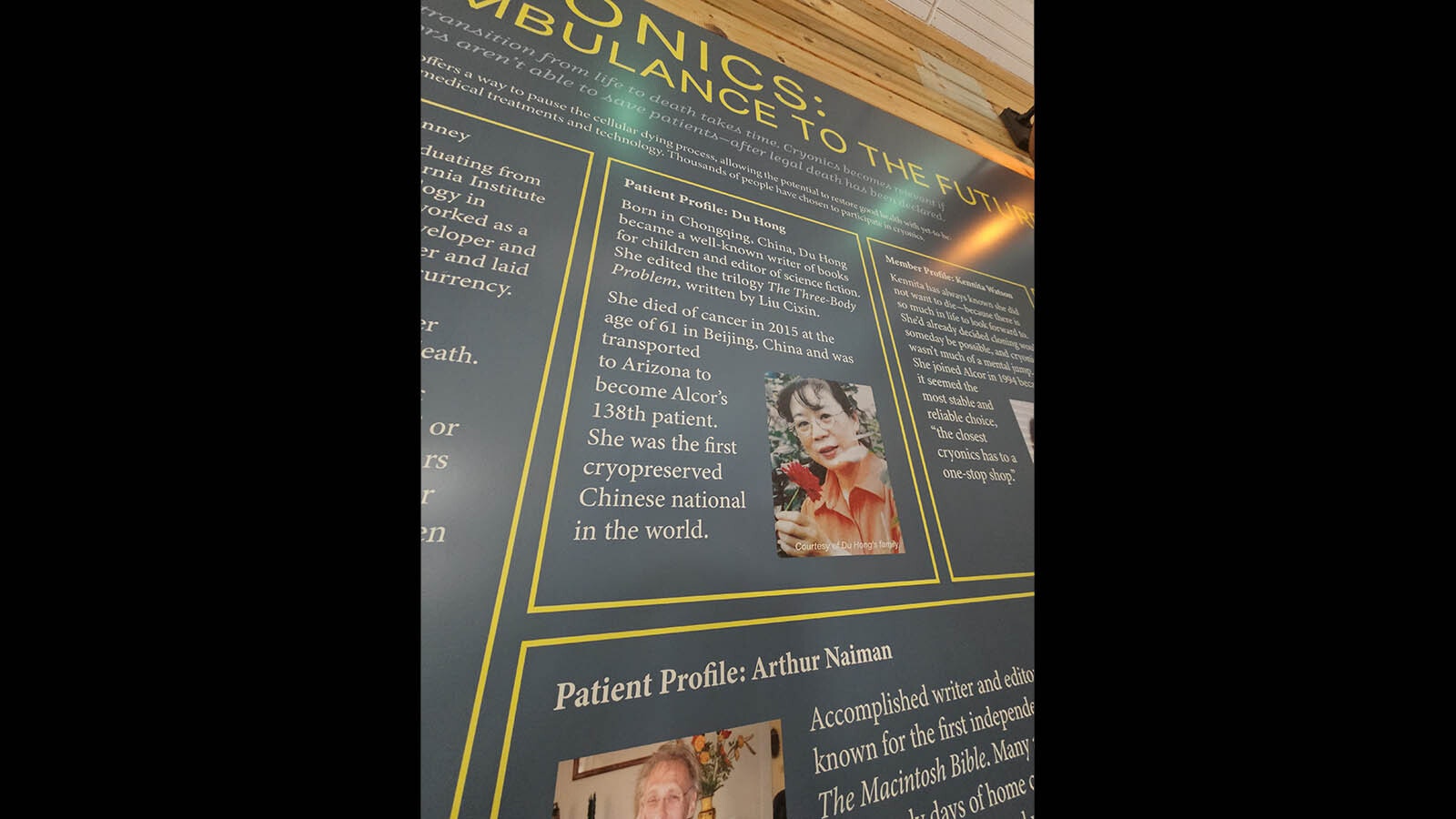

Alcor has 227 cryopreserved patients and 1,427 members. Included among its patients is the brain of Boston Red Sox baseball icon Ted Williams, who died in 2002 due to complications from heart disease. Software developer and bitcoin pioneer Hal Finney, who died in 2014 from ALS, is also among Alcor’s charges.

Arrowood said he knows that his odds of being revived are slim. But he feels a slim chance is better than no chance at all, and he can be part of helping advance the science, bettering the chances for others in the future.

Arrowood points out that cryonic preservation is already being used with success for some human cells.

“Embryos and eggs and what have you are stored in liquid nitrogen indefinitely, and they ultimately result in humans,” Arrowood told Cowboy State Daily. “That’s just a scientific fact.”

The scale and complexity involved there are much less, Arrowood acknowledged, but to those who say it’s impossible. He points out that many scientific advances, including the flight of humans in airplanes, were once thought impossible.

“We are studying death to extend life,” he said. “And that might be life extension through emergency trauma treatment-induced hypothermia. It might be life extension because we can clone endangered or near extinct animals. It might be life extension because you can go deep into space and survive now.

“It might be life extension because, ultimately, 200 years from now we find a way when your heart quits working to keep your brain going long enough to fix your heart.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.