When United Airlines Flight 409 took off from Denver’s Stapleton Airport en route to Salt Lake City on Oct. 6, 1955, one of the 66 on board was a soldier on his way home from Germany to see his wife and 9-month-old baby.

Also onboard were a sergeant and captain from Hill Air Force Base in Utah, 17 young U.S. Air Force inductees headed to California and five members of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir returning from a concert tour in Europe. There were passengers from Michigan, California, Nebraska, Pennsylvania and other states.

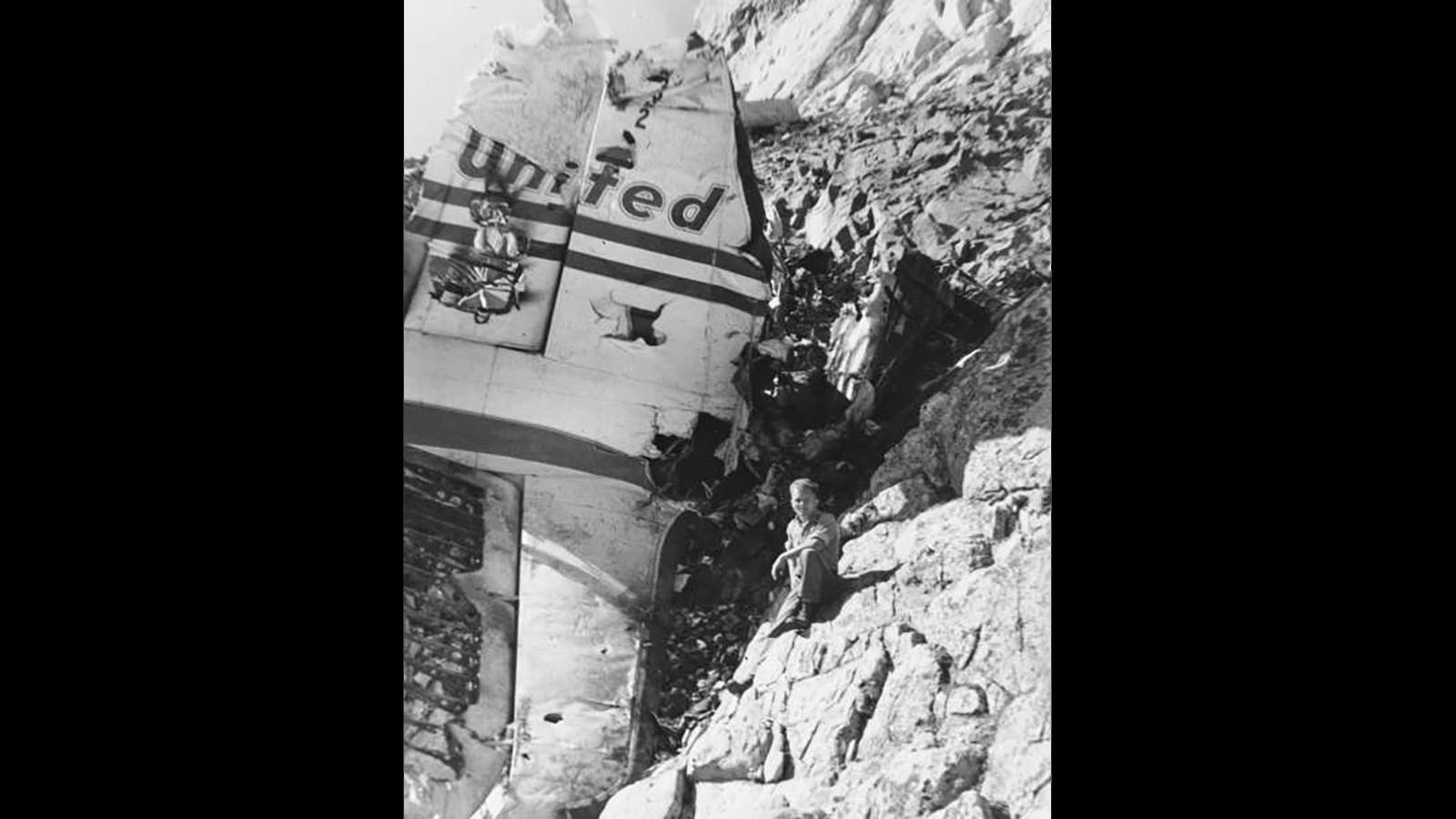

The Douglas C-54B’s flight had originated in New York City, stopped in Chicago then Omaha, and changed its crew in Denver. Captain Clinton C. Cooke Jr. was at the controls and First Officer Ralph D. Salisbury Jr. sat in the co-pilot seat. Stewardess Patricia D. Shuttleworth was taking care of the passengers.

The unpressurized four-engine plane lifted off from the Mile High City at 6:33 a.m. and headed north. Flying by visual flight rules on a scheduled route to Salt Lake City, plans called for a cruising altitude of 10,000 feet and navigation along what is now Interstate 25 and Wyoming’s I-80 corridor. The plane was supposed to check in by radio at Rock Springs around 8:30 a.m.

No Contact

That check-in never happened.

Repeated efforts were made to establish radio contact and an emergency was declared, and four hours later what was left of the plane was discovered just below Medicine Bow Peak west of Laramie.

Carbon County Museum Director Tom Mensik has studied the crash and produced a video about it, and said people on the ground reported hearing the plane smash into the peak.

“There were a bunch of ranchers nearby and people in the Medicine Bow Forest that heard a loud boom and a loud explosion,” he said. “A couple of people saw the plane fly over and didn’t really notice anything out of the ordinary.”

Mensik said the crash triggered “probably the first mass-casualty event” in Carbon County. The plane wreckage’s was discovered at 11:40 a.m. by a Wyoming National Guard pilot, and there were other planes in the air from the Civil Air Patrol and United Airlines.

The plane struck some 60 feet below the summit of the 12,005-foot peak, leaving two large smudge marks and four scars in a horizontal line likely caused by its four engines and propellers hitting the vertical rock cliff.

The force of the impact and explosion disintegrated the aircraft over a wide debris field. Nearly 70 years later, much of those pieces remain where they fell, a minefield of rusty remnants of the 66 who were killed in what, at the time, was the worst U.S. air disaster ever.

Mensik said the location straddled the Carbon County and Albany County lines and after discussion, the Carbon County Sheriff’s Office was given the task of leading response efforts.

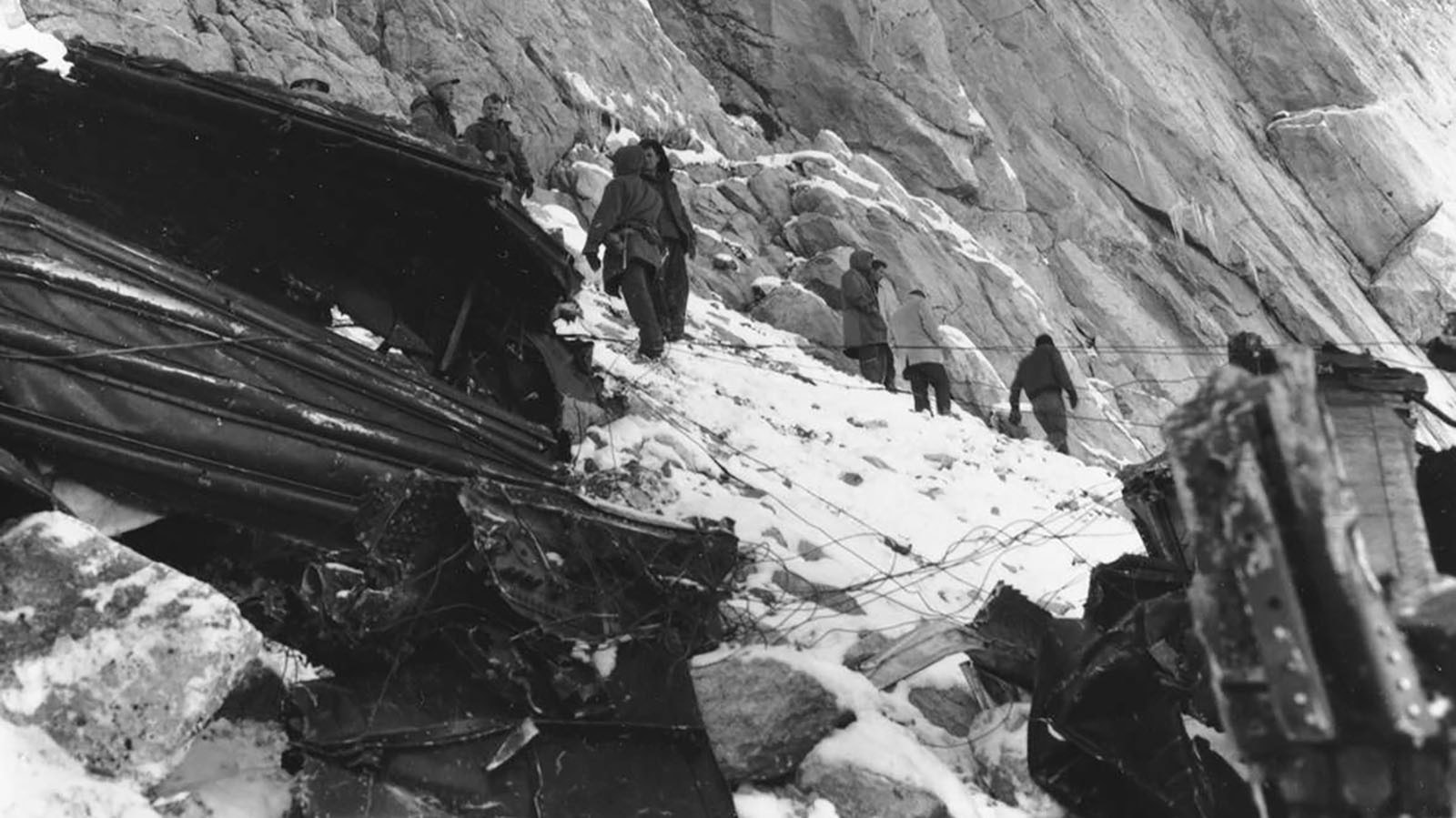

“It really tested the disaster response of the region,” he said. “Even on a good day, it’s not easy to hike a 12,000-foot peak. They sadly discovered bodies all over the site and even bodies that had been launched on the other side of the ridge after the impact.”

A Grim Search

A news account of the crash in Colorado’s Greeley Daily Tribune on Friday, Oct. 7, reported climbers battled high winds and deep snow in their efforts to retrieve the bodies.

“Rescuers who struggled through deep snow and up the precipitous peak Thursday counted about 50 bodies before rising winds and darkness forced their retreat,” an Associated Press reporter wrote. “They descended to a base camp more than a mile from the tragic scene.”

Mensik said that a University of Wyoming camp was used as a command center the search efforts and cabins there were converted to a temporary morgue. Those involved in the rescue operation included 10 members of the University of Wyoming Mountain Club.

Laramie resident Marjorie Daley said her father, William “Bill” Daley, and two of his closest friends, Keith and Robert (Bob) Lambertsen, were with the Rawlins Fire Department when the plane crashed.

“The rescuers had to make their way around the lake, and as they did so, they started finding body parts,” she said. “Keith mentioned that he found a torso and the only way he knew it was from a woman was because the torso had on a corset. He also said that the body was bright orange. They had expected the possibility of carbon monoxide poisoning (cherry red) but had never seen anyone who was orange.”

Daley said she remembers her dad talking about feeling around in the water looking for body parts.

“All the men looked at each other at this point and changed the subject,” she said. “All three men were military veterans and ranchers, so they were not particularly squeamish. Everything became a funny story for them, except this airplane crash and the rescue work. They never managed to find the lighter side.”

Waiting For Word

In Laramie, hotels for United Airlines personnel and air crash investigators were hard to find. The Shriners had booked the city for a convention and after the crash, some Shriners gave up their rooms, while the university also offered lodging to help support response efforts.

Rescuers found the tail section of the plane severed from the fuselage and wedged in an opening of the cliff. The passenger compartment and cockpit were all in pieces on impact.

Among the loved ones waiting in Salt Lake City were the wife and 9-month-old son of Cpl. Richard Hawkins, 22, of Eureka, Utah. He and another soldier on board were to be discharged from the Army after their two years of service.

“She traveled from the tiny central Utah town to the Salt Lake airport to meet him,” the Associated Press reported at the time. “And she brought their only child — 9-month-old Sydney Lee Hawkins — so her husband wouldn’t have to wait any longer than necessary for his first look at the child he had never seen.”

A husband and wife from Pennsylvania were also at the Salt Lake airport waiting for two couples to arrive on Flight 409. J.B. Felten and his wife had won a coin toss to get the last two seats on a direct flight from Chicago to Salt Lake, while their friends had to take the Denver flight.

“Pausing frequently as tears welled in his eyes, Mr. Felten told how he and Mrs. Felten were in Salt Lake City and the broken bodies of four intimate friends and associates rested on the cold slopes of Medicine Bow Peak,” the Salt Lake Tribune reported Oct. 8, 1955.

The 17 Air Force inductees onboard Flight 409 ranged from 17 to 21 years old and came from Arkansas, Colorado, Nebraska and South Dakota. They were headed to Parks Air Force Base in Dublin, California.

Mensik said a pulley was used during recovery operations to pull larger sections of the wreckage off the mountain, while members of the Wyoming National Guard used large recoilless rifles to shoot debris stuck in the rugged crevasses on the peak to break it up and allow it to fall down the steep areas of the mountain.

Mensik said the coordination and response to the remote crash site was massive.

“The fact that the response of within four hours of finding this crash to within a day or two having hundreds of people up there scouring for victims and investigating, setting up a morgue site, setting up a command center, it was pretty remarkable,” he said. “Even by modern standards, that is a really, really good response time for a plane crash.”

Wind, Visibility And Off Course

A Civil Aeronautics Board investigation of the crash released was released March 22, 1957, and reported that the plane did not appear to have mechanical issues prior to hitting the mountain. All engines were operating. The weather for the planned route was generally fair; however, Medicine Bow Peak had broken to overcast conditions, light snow showers and winds from the northwest at 30 to 40 knots.

Those winds could have increased to 50 to 60 knots around the peak area and created downdrafts and turbulence on the east side of the mountain.

Cooke, the pilot, had qualified to fly the route in August 1951, and had flown it 45 times in the 12 months preceding the crash. That day, the plane was several miles west and 15 degrees off course from the route he had signed off on in Denver.

“According to his superiors in the company, he had never been known to deviate from a planned route without advising the dispatcher,” the Civil Aeronautics Board reported. “Considering the navigation equipment on board the aircraft, the fact that all pertinent ground facilities were functioning in a normal manner, the pilot’s knowledge of the terrain, and the good visibility prevailing that day, it does not seem possible that a navigational error of any magnitude could have been made.”

The board investigated a heater found at the crash site to try and determine if poisonous gasses entered the cockpit. It ruled that the theory seemed impossible since the aircraft was flying at 10,000 feet and hit the mountain at 11,570 feet — indicating it had climbed.

Pilot Error

In the end, weather, mechanical difficulties, weight and load distribution issues all were ruled out as causing the crash. The plane had the proper maintenance and the pilots the proper training.

The cause of the crash came down to “the pilot deviated from the planned route,” the board concluded.

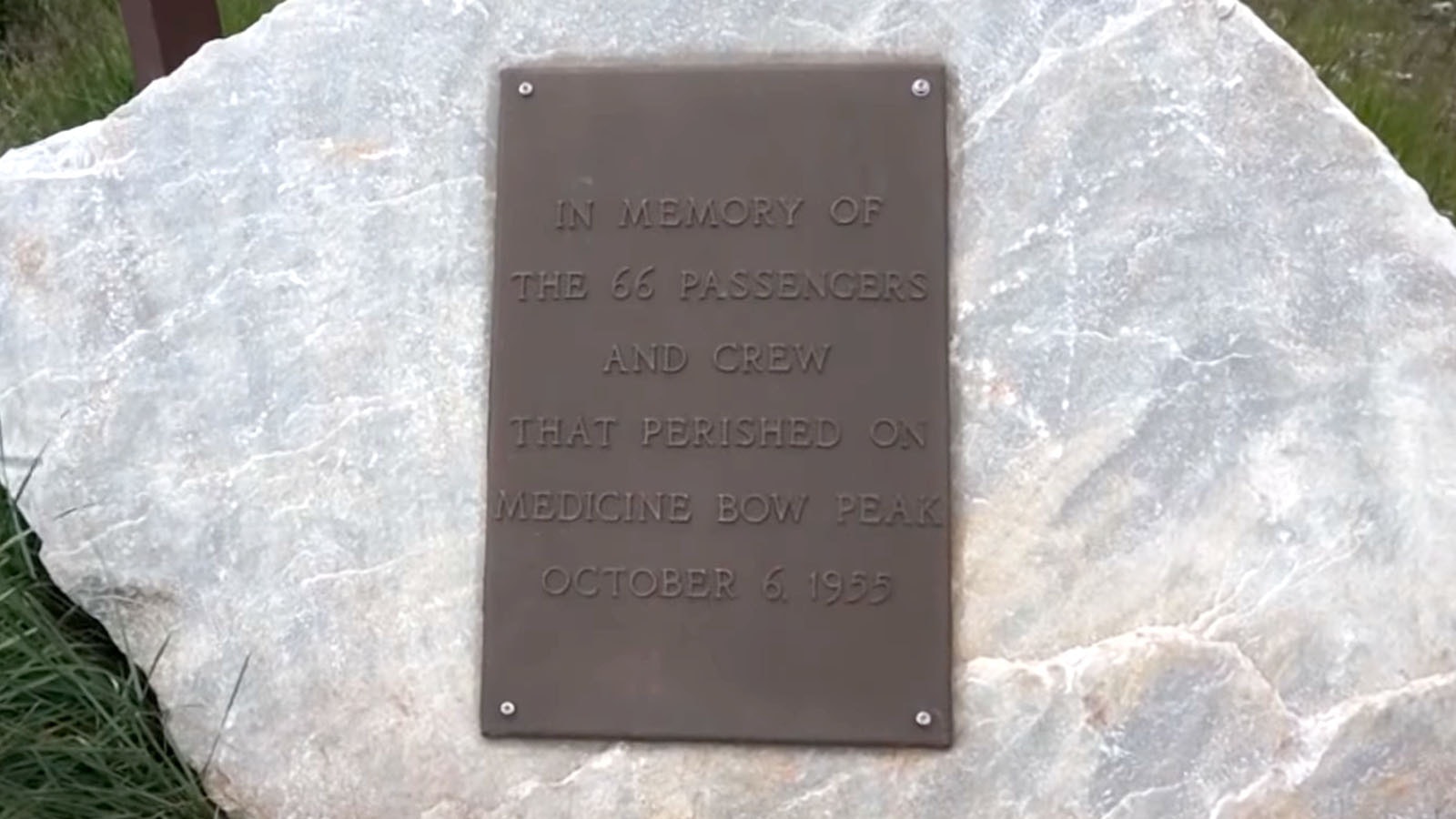

Menzik said the crash’s effect on the Laramie community was important enough for a memorial plaque to be erected to honor the victims in 2001 at the highest point on the Snowy Range Scenic Byway, and scars on the mountain remain visible.

“Having a plane crash into the side of a mountain is a huge, huge tragedy no matter where it is,” he said. “It’s not said that anyone (locally) personally knew anyone in the crash, considering it originated in New York … (but) it’s just kind of a personal trauma and scar on such a beautiful place.

“People still hike around in that region at the base of the peak and still find pieces of the airplane around.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.