Dear editor:

As retired wildlife biologists who worked most if not all of our careers in Wyoming, we have an uncommon perspective on wildlife and its management. Collectively we hold over 500 years of formal education and field experience in managing wildlife populations, conducting wildlife research, and in interacting with Wyoming’s public on many wildlife issues. But mostly we are just Wyoming folks who love our wildlife and want to see it conserved for the future.

The 2022-23 winter in Wyoming was one of the harshest on record. Animal death rates were over 50% in several herds with deer and pronghorn in western Wyoming hit the hardest. We know the herds will bounce back, but we don’t know whether populations will ever bounce back to the numbers present in the fall of 2022. Time will tell, but, like most wildlife observers in Wyoming, we know numbers of pronghorn and mule deer have declined for many years for many reasons.

We must address claims that wildlife is not negatively impacted by energy development. These anecdotal statements typically go something like, “pronghorn and deer aren’t harmed because we see them in the gas fields; we see them sheltering from the weather beside tank batteries, etc.” In truth, although some animals still use these developed areas, the science clearly tells us that most do not.

We are aware of the benefits of the oil and gas industry to Wyoming and to all of us who live here— jobs, lower taxes, better schools, and a more robust economy. We also know Wyoming plays a vital role in powering America. But this does not mean we can’t be honest about the impacts that development, including energy, has on our wildlife. Failing to acknowledge these impacts when development plans are made handicaps our ability to minimize the negative effects.

Wyoming leads the nation in energy development, and it has also led the way in evaluating and documenting the impacts of energy development on wildlife.

In fact, most of the science around big game and sage grouse and energy has been done in Wyoming, not some faraway place with different herds or landscapes.

The results of most Wyoming studies lay out a clear picture that most aspects of energy development are not beneficial to our wildlife. Rather, the human disturbance (e.g. traffic, noise, etc.) and loss of habitat associated with energy development negatively affect them. Casual observations can be a source of ideas to be tested, but long-term studies provide an unbiased, science-based analysis of the real impacts — impacts that might not be obvious or expected.

Examples of such studies for mule deer and pronghorn include a long-term mule deer study showing that deer wintering on the Pinedale Anticline experienced a 36% population decline as a result of energy development, despite mitigation efforts. From 2001 to 2014, the number of mule deer wintering on an area near Pinedale declined by 54% after oil wells were drilled. Meanwhile deer numbers across Wyoming declined by 24% over the same time frame. In the same area, researchers found pronghorn avoided well pads and progressively spent less time in the gas field, mostly leaving traditional winter ranges in favor of areas with no development.

Research has also shown deer speed up their movements as they migrate through gas fields and so use these habitats less than when moving through unimpacted areas. Another study showed that migrating mule deer in Wyoming reduce time spent on traditionally preferred feeding stopovers in response to increasing development. And mule deer migration sharply declines through areas with surface disturbance exceeding about 3%. Similar disturbance thresholds have also been identified for pronghorn.

A 14-year study on a mule deer herd south of Rawlins found that coal-bed methane development disrupted the herd’s ability to access the best quality forage during springtime green-up. This is an important time of the year for antler growth, nursing of offspring and herd growth. This herd declined by 39% when energy development occurred along its migration corridor.

Finally, a newly published study associates long-term declines in pronghorn productivity with increases in oil and gas development.

We all want to have our cake and eat it too, but deep down, we know there are no free lunches. This is also true with energy development and negative wildlife impacts. Common sense tells us that loss of habitat to roads, well pads and other facilities take a toll on deer, pronghorn and many other species of wildlife. Human activities and disturbances increase big game use of the fat reserves needed to make it through a tough winter. The research supports these common-sense notions.

Energy production is essential for our state and nation, but it needs to be thoughtfully planned, with an honest assessment of the impacts. Many energy players have actually stepped up to fund this research.

Many of Wyoming’s most ardent wildlife supporters work in the oil and gas industry and hunt and view wildlife on a daily basis. We are on the same side! Now we have to decide how to better use what we have learned to conserve these incredible resources for our grandchildren. Ignoring the wealth of science Wyoming has worked hard to produce benefits no one, especially Wyoming’s world class wildlife.

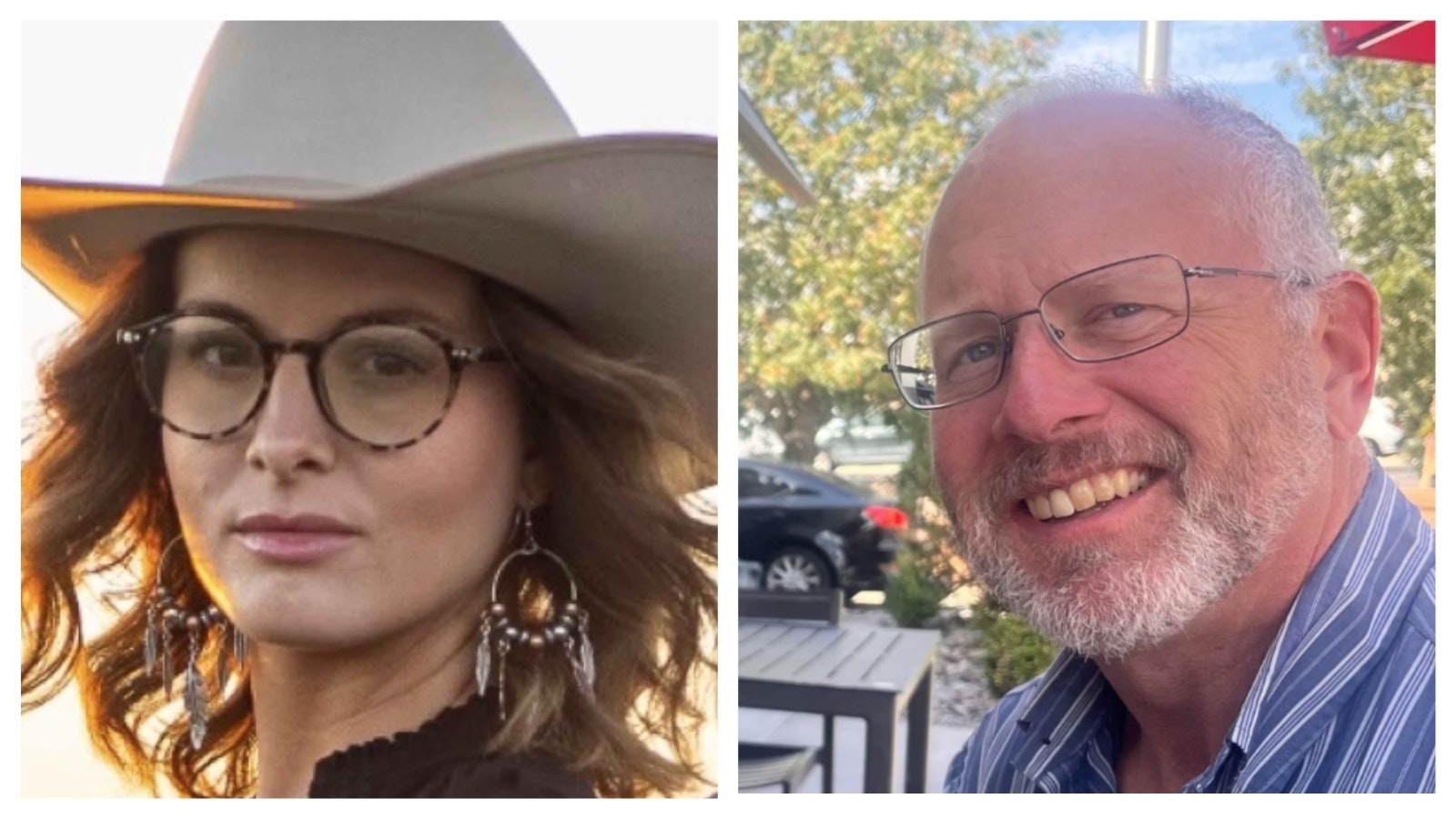

Submitted by 18 retired agency, private and university wildlife professionals listed alphabetically:

Dr. Bill Alldredge, Joe Bohne, Tom Christiansen, John Dahlke, John Emmerich, Walt Gasson, Rich Guenzel, Dr. Harry Harju, Bert Jellison, Duane Kerr, Bob Lanka, Chris Madson, Dave Moody, Reg Rothwell, Tom Ryder, Dan Stroud, Dan Thiele, and Mark Zornes.