Every good story needs an antagonist. For the classic Western novel “Shane,” the real-life legacy of Natrona County Albert J. Bothwell fits the bill.

In life he was alleged to have had pet wolves while also leading efforts in Colorado and Wyoming to destroy them.

He married the widow of an employee who died, then had children with another woman while married to his first wife.

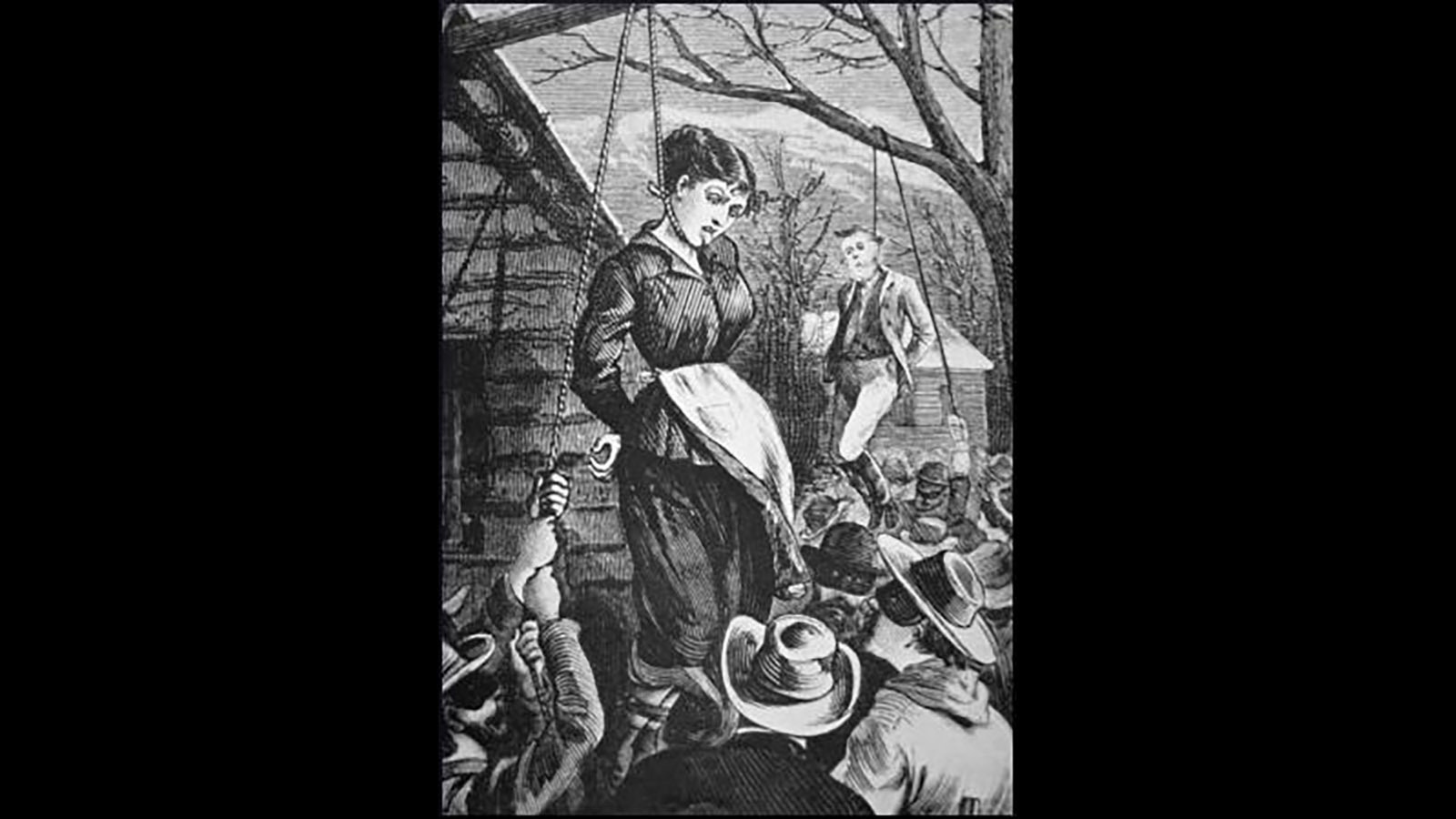

And most dastardly, he hung his neighbors from a tree, escaped prosecution, acquired their land and went on to greater respectability as a leader among the Wyoming Stockgrowers Association and an agent for the Western Breeders Association.

Bothwell may not be as famous as some other Wyoming outlaws, but he rolled like an original Western gangster.

The Hanging

Bothwell’s role in 1889 in accusing homesteaders Ellen Watson and James Averell of stealing cattle, and then helping hang them with five other ranchers, became one of the most-chronicled and worst examples of the Western lawlessness. His efforts to demonize small ranchers helped lead to the Johnson County War.

Averell, who had been on his 160-acre Horse Creek homestead for four years before Bothwell arrived and bought adjacent land, had written a letter in the local paper that called into question the “land grabber who is only camped here as a speculator in land under the desert land act.”

Watson had succeeded in getting a 160-acre homestead in her name, a cattle brand, and small herd of cattle allegedly from a man headed farther west.

In 1888, the Cheyenne Daily Leader reports that A. J. Bothell bought 1,500 head of cattle from Ed A. Page in Carbon County. That year he also tried to create a town named after himself by homestead claims and desert land entries on Horse Creek land. The town went nowhere.

Bothwell and five others banded together July 20, 1889, to find, seize and then hang the couple who may or may not have been married, but they had a marriage license.

The San Francisco Examiner reported the story that charged the men with the murders, and how the court allowed $5,000 surety bonds to be posted. Bothwell was described as a “postmaster and a merchant.”

Bothwell and others readily admitted their roles in hanging the pair, accusing them of stealing cattle. The Examiner reported they said, “This will be the policy of the cattleman hereafter.”

“Prominent men in Rawlins say the town will be razed before the punishment of the lynchers is permitted,” the newspaper reported.

Witness Disappears

History shows the lone witness to the hanging — a friend of Averell’s who tried to stop the lynching by firing a revolver but was driven off by the lynchers returning fire — shared his account of the event with newspapers. Shortly after that he disappeared.

There was never a trial for the hangings, charges were dropped. Bothwell would eventually end up with the couple’s land.

The classic novel “Shane” depicts the struggle between cattle barons and homesteaders in Wyoming. It includes the killing of a homesteader by a wealthy rancher. Bothwell was a good template for the character.

Wolves As Pets

Casper historian Tom Rea in his book “Devil’s Gate” characterizes Bothwell as a “mean” neighbor.

In 1886, Bothwell dared to put a fence across the Oregon Trail. In 1888, he shot a horse out from under a rider during a dispute over ownership of draft horses. In 1894, he worked to prevent another neighbor from becoming a member of the Wyoming Legislature by trying to have him arrested for killing a steer.

Turns out the steer execution was legitimate because he was in business with its owner. The case was dropped.

“Bothwell also kept wolves as pets, and at least once in 1903, the wolves attacked a ranch hand who was trying to feed them, tearing up the man’s left arm and shoulder,” Rea wrote. “Bothwell’s neighbors remembered the wolves for a long time and recalled that when they howled in their pens, wilds wolves and coyotes would answer back from the ridge tops.”

It may have been those wolves were the same ones Bothwell had his ranch hands capture in January 1899 as he prepared to address stock associations in Denver and then Cheyenne. An article in The Denver Post and reprinted in the Natrona County Tribune on Jan. 26, 1899, tells of Bothwell sending wolves to Denver to be used during his talk on why wolves should be “exterminated.”

“A.C. Brown, a helper at the yards, is suffering from bites and scratches and clawings, which are serious and which may prove fatal,” the Post reported. “Several other men bear witness of wolf caresses.”

The paper reported after the incident while trying to get wolves into separate crates.

“There they will be fed and cajoled as far as possible into good nature until the momentous day of the paper (from Bothwell),” the Post reported. “They will then be muzzled and brought on the stage where thousands may see them, while Mr. Bothwell sets forth the necessity and the mans of destroying them and their kindred.”

The wolf antagonist and protagonist Bothwell was born Valentine’s Day, Feb. 14, 1854 in Galena, Illinois. Newspaper accounts have him traveling to Cheyenne in the early part of the 1880s. On Nov. 26, 1887, he is appointed a notary public in Sweetwater and Carbon counties.

In 1888, the Cheyenne Daily Leader states that A. J. Bothwell bought a Carbon County herd of 1,500 head of cattle from Ed A. Page.

Respect And …

During his life, Bothwell would become an agent of the Western Breeder’s Association. He would also be involved in a well-publicized federal lawsuit involving his Natrona County ranch and the creation of the Pathfinder Dam because he valued his property much higher than the Bureau of Reclamation wanted to pay.

He fought the government again in 1919 over a fence. An article in the Casper Tribune-Herald on Sept. 22, 1919, has him contending in court why the government should not collect $42,000 from him for illegal fencing.

Bothwell’s family life also proved contentious.

Information on Bothwell at Find A Grave shows he married his wife, Margaret Gray, in 1891. She moved with him to his Wyoming ranch along with two children she had with a Henry S. Church, who died in Cheyenne in 1885 and had worked for Bothwell.

However, twin daughters attributed to Bothwell and his second wife, Alice Wadsworth, who worked for the family, were born in 1906.

Messy Divorce

On July 20, 1910, his lengthy divorce case with wife Margaret G. Bothwell was among the headlines in the Natrona County Tribune.

“(The case) which had the promise of being one of the hardest fought cases in Natrona County and one that would bring forth some testimony that would be racy in the extreme, came to a sudden and unexpected termination last Friday afternoon,” the newspaper reported.

While “Mrs. Bothwell” had asked for $75,000, the court on only the testimony of Albert Bothwell ruled in favor of him and his wife agreed to accept a $10,000 payment and release him from other claims.

During his testimony, Bothwell said he had left his wife at a boarding house in Denver in 1903 while he traveled to Natrona County to check on his ranch. He testified his wife then, without informing him, traveled to Chicago and New York City, and later brought action against him for divorce.

“She was very much interested in the work of ‘free thought’ or divine science, which teaches right living and right thinking,” the Natrona County Tribune reported. The article stated Albert Bothwell pursued many depositions from Denver, Chicago and New York and those dispositions were the reason his wife yielded “to the terms of her husband.”

On June 8, 1916, the Natrona County Tribune reported that Bothwell was still fighting for himself and offering a $500 reward for evidence that would lead to the conviction of those responsible for stealing “30 head of fine horses from the pastures of the Bothwells on the Sweetwater River.”

As age overtook him, Bothwell would go on to sell the ranch and move to California, leaving his lawlessness and brutality behind.

He died in Los Angeles in 1928.

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.