Most hunters who think they’ve bagged an extremely rare mule deer-whitetail hybrid probably actually haven’t, but even if they have it’s not a sign Wyoming’s prized mule deer herds are in danger.

“You’ll hear that a lot in the taxidermy industry. People will say, ‘Oh this must be a hybrid.’ But usually it’s not. I’ve never seen an actual hybrid come through my taxidermy shop,” Kevin Monteith told Cowboy State Daily.

Monteith is a biologist with the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming and also a taxidermist.

There are certainly a few mule deer-whitetail hybrids around Wyoming, but their numbers are few, probably fewer than “the single digits” of the percentage of the deer population in any given area, Monteith said.

And although the mule deer population is struggling in Wyoming and across the West, crossbreeding with whitetails isn’t common enough to be a viable threat to mule deer, he said.

How To Spot A Crossbreed

People sometimes mistake deer for hybrids because of typical features, such as body mass or antler and tail structure, Monteith said.

However, those aren’t always reliable markers for whether a deer is a hybrid. There might be enough variation within each species in body size, coat color, tail color and other common features to throw observers off.

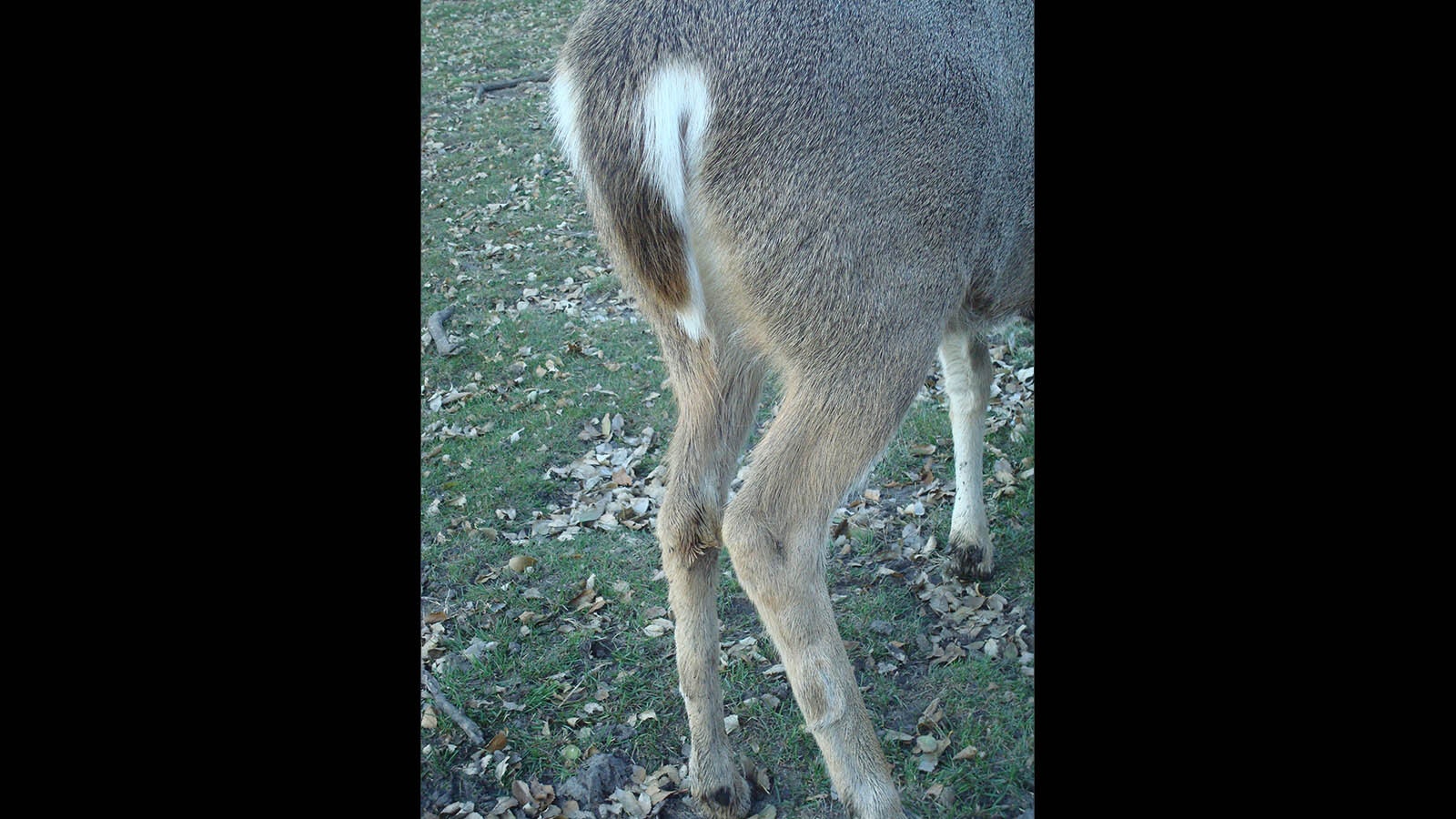

A dead giveaway is the metatarsal gland. Those are glands that deer have on the outside of their rear legs, often appearing under a tuft of hair growing in one direction.

The glands are about only an inch in size on whitetails, but are much larger — several inches long — on mule deer. So, glands that fall between those two size ranges are a clear indicator that the deer is a crossbreed, Monteith said.

Awkward Little Buck

Mule deer and whitetail frequently share habitat, but only very rarely interbreed.

As to whether it’s more common for a mule deer buck to pitch woo with a whitetail doe, or the other way around, “it can go either way,” Monteith said.

Earlier in his biology career, he worked with captive deer of both species. One year during the rut (mating season), a mule deer buck broke out of his pen and bred with a whitetail doe.

The result was a hybrid buck that seemed confused about some things, Monteith said.

Whitetails and mule deer take different tactics when evading predators. Whitetails just run.

“The whitetail is an all-out runner. They really haul the mail and can cover a lot of ground,” Monteith said.

Mule deer put their stiffened legs together and bounce. It’s called “stotting,” as the deer move in what could be described as a rapid “boing-boing-boing” pattern, he said.

Monteith said it’s a pattern of movement mule deer adapted to escape predators across the rugged, uneven terrain they frequently occupy.

In the case of the young hybrid buck, he seemed confused over what to do when spooked.

“He would open up and run, and then he’d stot for a couple of rounds. Then he’d open up and run, and stot for a couple more rounds,” he said.

The buck’s odd behavior showed that hybrids “don’t quite know what to do with themselves,” which could hurt their chances of survival in the wild.

Some crossbreed species are infertile, but mule deer-whitetail hybrids are generally capable of reproduction, Monteith said. But again, their confused behavior might make it difficult for them to survive in any significant numbers.

Are Whitetails A Problem For Mule Deer?

There is a noticeable pattern of whitetails growing in number and expanding their range, while mule deer continue to lose ground.

A common assumption is that whitetail aggressively drive mule deer out, or out-compete them for resources. That idea has been central to an ongoing debate over whether the Wyoming Game and Fish Department should manage whitetail and mule deer as separate species and split management of and hunting seasons for them.

However, as to whether whitetails really are a threat to mule deer, there’s no clear answer yet, Monteith said.

When resources such as forage are scarce in areas where mule deer and whitetail share habitat, having both species there might put more strain on those resources, he said.

But he doesn’t think it’s a case of whitetails bullying mule deer and running them off of food.

Whitetails and mule deer also respond differently to changes, such as land development and habitat fragmentation, he said. Generally speaking, whitetails are much better at adjusting to human presence and infrastructure.

Disease also can be a factor, Monteith said. For example, whitetails can be carriers of a type of brain worm that’s fatal to mule deer if it’s transmitted to them.

Mule deer are facing a wide range of challenges all over the West. And while whitetails might be “just one more thing” in some areas, they likely aren’t a primary cause of mule deer decline, Monteith said.

Mark Heinz can be reached at mark@cowboystatedaily.com.