Wyoming practically marks time by its blizzards. The way hurricanes frame bygone decades in Florida or how Alabama counts college football championships.

No big deal. Been there, shoveled that.

There was the winter of 1979 when some of the coldest temps ever recorded in the state made life miserable. The blizzard of 1955 dumped 40 inches of snow on Sheridan, Wyoming, in two days. In April! Still a record.

The Siberian Express of 1933 was a storm that began in Russia then walloped Wyoming with record-low cold temps, including minus 66 in Yellowstone — the coldest temp ever recorded in the Cowboy State.

And who could forget the Winter of 1887? Considered one of the harshest since records have been kept, more than a half million head of cattle died that season.

But those who lived through the Blizzard of 1949 — some of them hardened Wyomingites and centenarians — say it was the snowiest, coldest and longest storm they’ve ever seen. And they hope to God they never seen another one like it.

Accumulation measured in feet. Winds clocked 65-80 mph. Snow drifts buried cars, houses, and telephone lines. Double-digit subzero temperatures for weeks on end.

With little let-up, the storm that began Jan. 2, 1949, raged for 48 days. At the petitioning of four governors from affected states, President Truman declared the region a disaster area and wrote a blank check for “Operation Snowbound,” instructing members of the Army, Navy, Air Force and National Guard to “dig out the West.”

The devastation to livestock was heartbreaking. Wildlife was killed off in droves. Thankfully, human fatalities were relatively few.

The only reason the death toll was not higher for every living thing was because of the comradeship of the Wyoming people. Heroism was everywhere. Selflessness was brought to the surface in the face of hardship.

The Blizzard of ’49 brought out the best in Wyoming.

No One Saw It Coming

Dubbed the “Great White Death,” one of the things that made the 1949 snowstorm so virulent was that no one saw it coming. Not even the experts.

Sure, by today’s standards, meteorology 75 years ago was less the exact science than it is today. Still, one wonders whether this particular snowstorm could have been anticipated by even the great Don Day.

“Expect partly cloudy skies today with highs in the 30s. Occasional snow flurries are also a possibility.”

That was the weather forecast for the eastern half of the state on Jan. 2, 1949. After a gorgeous sunny day across the state to start the new year, Jan. 2 began much the same, with mild temperatures and plentiful sunshine.

A train full of Northwestern fans returning to Chicago from the West Coast after watching their football team win the Rose Bowl against California had no idea when they made a stop in Cheyenne they would be there long enough to grow beards.

By late morning that fateful Sunday, an eerie dark gray cloud advanced from the northwest.

“It was like hitting a wall,” Bill Miskimins recalled in the Wyoming State Archives as he encountered the storm’s front while returning to his family’s ranch outside of LaGrange.

Helen Sides pushed aside the curtains on her kitchen window and observed, “... the sky looked foreboding and different than anything I had ever seen before or since.”

A ranchwoman from Manville named Frances Tschacher said she’ll never forget the charged feeling in the air. “It was like static electricity,” she said for a 2015 PBS documentary on the blizzard.

The Storm of the Century was on the way.

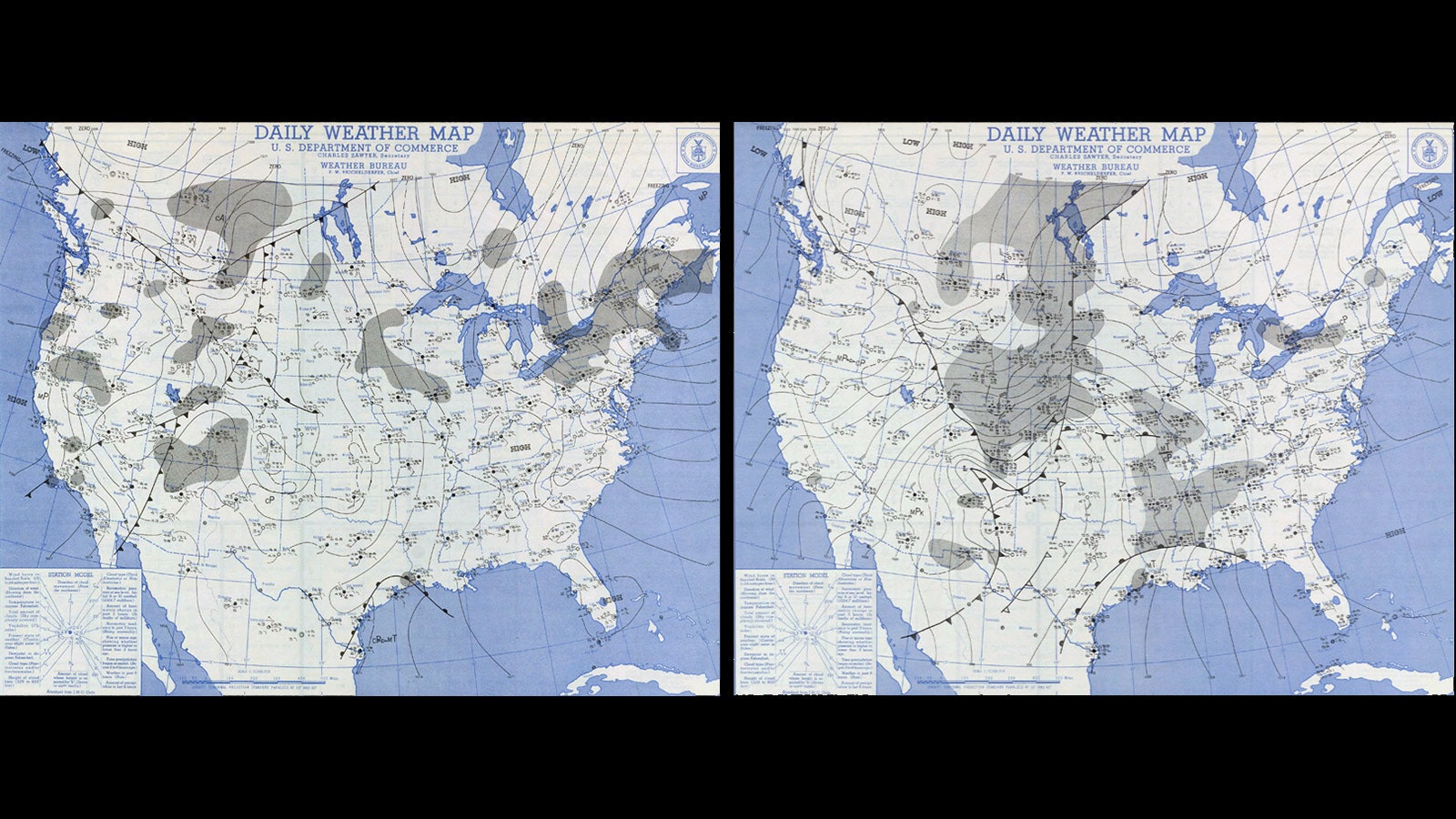

A low-pressure system consolidating over the southwest funneled moist air from the Gulf of Mexico northward. That energy met with an arctic high-pressure system pushing southward through the Canadian prairies. The collision of fronts took place in eastern Wyoming, and western South Dakota and Nebraska.

By the time a blizzard warning was issued out of Rapid City from the National Weather Bureau, it was too late. Every rancher in the vicinity could simply look up at the sky and know something wasn’t right.

Douglas ranch kid Larry Crummer was 14 years old when the snow started and never stopped.

“‘Look up here what we have over our heads,’” Crummer told his dad while they were outside getting the dairy cows in the barn ahead of the storm. “It was a perfect rainbow with the exception of the fact that it was upside down.”

When it came, it came on fast. The barometric pressure dropped so far, so rapidly it actually triggered false labor pains for many pregnant women.

In a matter of hours that Sunday afternoon, temperatures plummeted from mid-30s to below zero. Winds peaked at 66 mph and the snow piled up so fast, traveling motorists were buried before they could pull off the highway.

When the storm finally relented on Feb. 19, there were 17 Wyoming residents counted among the dead, 76 total over the region. Stranded motorists perished just hundreds of yards from the nearest house. Unaware, in the blinding whiteout, help was a porchlight away.

Some bodies would not be found until spring thaw, buried in the snow, frozen in the position they died in.

Arctic Blast

“Heavens to Elizabeth, did it snow,” Crummer recounted.

It wasn’t so much the snow, but the wind. In some places, bare ground could be seen. In others, something as small as a pebble could generate a 10-foot drift behind it.

By Tuesday, Jan. 4, 20-30 inches had dumped on Cheyenne in the initial storm surge. Laramie was bogged down in drifts. In other more remote areas of eastern Wyoming, help was still days from arriving.

And this was no powder day. It was snow from hell, say survivors.

“It was a funny snow. Real small, granulated, hard,” Bud Turner told Wyoming PBS. “There wasn’t any flakes to it. It was kind of like salt.”

Fine snow pellets would find their way into everything, even supposedly airtight enclosures.

In one instance, a rancher went to check on his bulls in the barn after the first storm. They were protected from the worst elements just fine, but wind had blown snow into the enclosure as fast as the bulls packed it down by pacing. When the rancher threw open the doors, he couldn’t believe what he saw — the animals’ horns were practically scraping the roof as they stood high atop the snowpacked floor.

Stranded motorists, thinking they would simply wait out the worst of it, found the sand-like snow would blow into closed vehicles and nearly bury them inside.

Powerful winds drove granular snow so hard it scoured the eyes, lacerated exposed skin and packed into the nostrils of domestic cows until they could not breathe.

Windblown snowdrifts set up like cement. In some cases, Union Pacific railroad workers digging out trains frozen to the tracks had to use flamethrowers and dynamite to free machinery from its icy tomb.

On Jan. 5, the snow eased and the sun popped out. But the wind never let up.

“It didn't make any difference. When it would blow, you never could see the sun. Your visibility was very limited. You couldn't see anything. It was the darnedest storm I ever saw,” Crummer said.

Tales Of Heroism And Heartache

Forty-eight hours after the initial surge, rescue efforts were well underway.

Wyoming National Guard's 187th Fighter Squadron began ground operations snowshoeing to Cheyenne-area homes to check on those snowbound.

With phone lines down, radio was all many had to connect with the outside world and learn anything about what was going on. Cheyenne radio KFBC broadcast around-the-clock advisories and did what they could to reunite loved ones.

“Anyone knowing the whereabouts of Mr. and Mrs. Jamison, believed to be somewhere between Cheyenne and Greeley, are asked to telephone KFBC,” a radio announcer said on a staticky Jan. 5 broadcast. “And here is a plea for help. There are six or seven men stranded at the Inland Drilling company approximately 30 miles north of Cheyenne. These men need food.”

More than 50 trains with 8,000 passengers aboard were stuck in snowdrifts on rails that were impassable. Passengers thinking they were going from Chicago to San Francisco were not dressed for extreme cold. They melted snow for water and coffee and raided the dining car for food until it was gone.

The Red Cross served 1,700 meals a day to stranded railroad passengers during the first three days of the storm.

By Jan. 6, Wyoming Department of Transportation snowplows were making some headway, although efforts were hampered when equipment broke down after drivers hit something solid like a car or a frozen cow. As quick as some stretches of highway were cleared of snow, they would drift back in again.

Acting governor Arthur G. Crane declared a state of emergency for Wyoming. State funds were released, federal aid would be on the way. But for many it would be too late. Crane was Wyoming’s secretary of state before he became governor just a day into the Storm of the Century on Jan. 3, 1949. He stepped in for Gov. Lester C. Hunt, who had to resign to begin serving in the U.S. Senate.

In the first few days, when it became apparent help was not coming, stranded motorists struck out on their own in search of shelter. Those who made it to nearby ranches were graciously taken in by homeowners even to the point of severe overcrowding.

For three days these makeshift B&Bs kept countless people alive through the ordeal.

“There was no question you would take them in and make them comfortable,” said Loretta Jewel of Carpenter.

Some did not survive, however. Jewell recalled the case of Andy Archiletta and his family.

They were visiting friends in Pine Bluffs when the storm blew in. He had 30 miles to get back to Hillsdale and everyone told him to stay the night. Andy thought he could beat the worst of it and headed out anyway.

Two miles outside of Burns, the Archilettas’ car bogged down in the snow. When rescuers found the vehicle the next day, the radio antennae was all they could see sticking out of the snow. They dug down to find the family frozen to death, huddled in the backseat around a hubcap Andy had pried from his tire and started a fire in.

Another man left his wife and baby in the car as he went to search for help. He died after falling off a snowdrift less than a mile from the Fred E. Warren ranch house in southeast Wyoming.

In yet another story of tragedy, one family of four was found frozen together in death — an aunt reaching toward a little girl, an uncle clutching a boy.

More Than One Storm

The Storm of the Century turned out to be not just the initial three-day event but a series of storms one after the other with unrelenting winds for two months.

As some travelers finally made their way out of the ravages of the weather and home safely, as more impulses continued to sweep across the state.

Six-foot drifts were reported on Highway 287 on Jan. 18 with a high temperature that day of minus 22. And new snow hit Jan. 23. Then on Feb. 6, another blast.

Kids were out of school for weeks at a time. The Rawlins-Laramie railroad line resumed sporadic service after two weeks of inactivity bringing mail to the town for the first time in 12 days.

In Lusk, drifts on Main Street rose to 12 feet high, 30 feet high just outside of town. Lusk residents, unsolicited, called local hotels and offered up their homes for lodgers who could not find an available room.

Casper received only 8-10 inches in the initial storm, but snowplows sent out from there to Lusk and beyond never returned.

In Goshen County, 65 men reportedly shoveled 30 miles to one rural home at the rate of a mile per hour to rescue survivors there.

By Jan. 13, even as The Branding Iron newspaper offered a five-dollar prize for the best blizzard story, it was becoming evident that the worst was yet to come, and the toll on livestock and wildlife would be brutal.

Country Folk Can Survive

Rural farms and ranches in Wyoming are all well-prepared for emergencies, for the most part. In 1949, some ranches were still not served by electric companies, or at least electricity was new enough that they still depended on heating oil, kerosene and wood-burning stoves for heat.

Ranchers in the West also are the original “preppers,” a self-sufficient demographic that cans food and sets store by having enough supplies to get one through a long weekend emergency or worse.

One ranching family was reportedly snowed in for nine weeks. When contacted, they declined help and claimed they were doing fine.

Still, codes were given on the radio asking rural dwellers to mark them the snow if they needed help. A single line in the snow meant a doctor was needed. Two lines, bring medicine. A large X meant a stalled auto. F stood for food. L for fuel and LL meant all was well.

The Civil Air Patrol — a voluntary branch of the Air Force — flew food, fuel and medical supplies to families, risking their lives in horrendous weather conditions.

They attached skis to their planes if they had to land and get someone to a hospital. Supplies were parachuted in from Lowry Air Force Base in Denver.

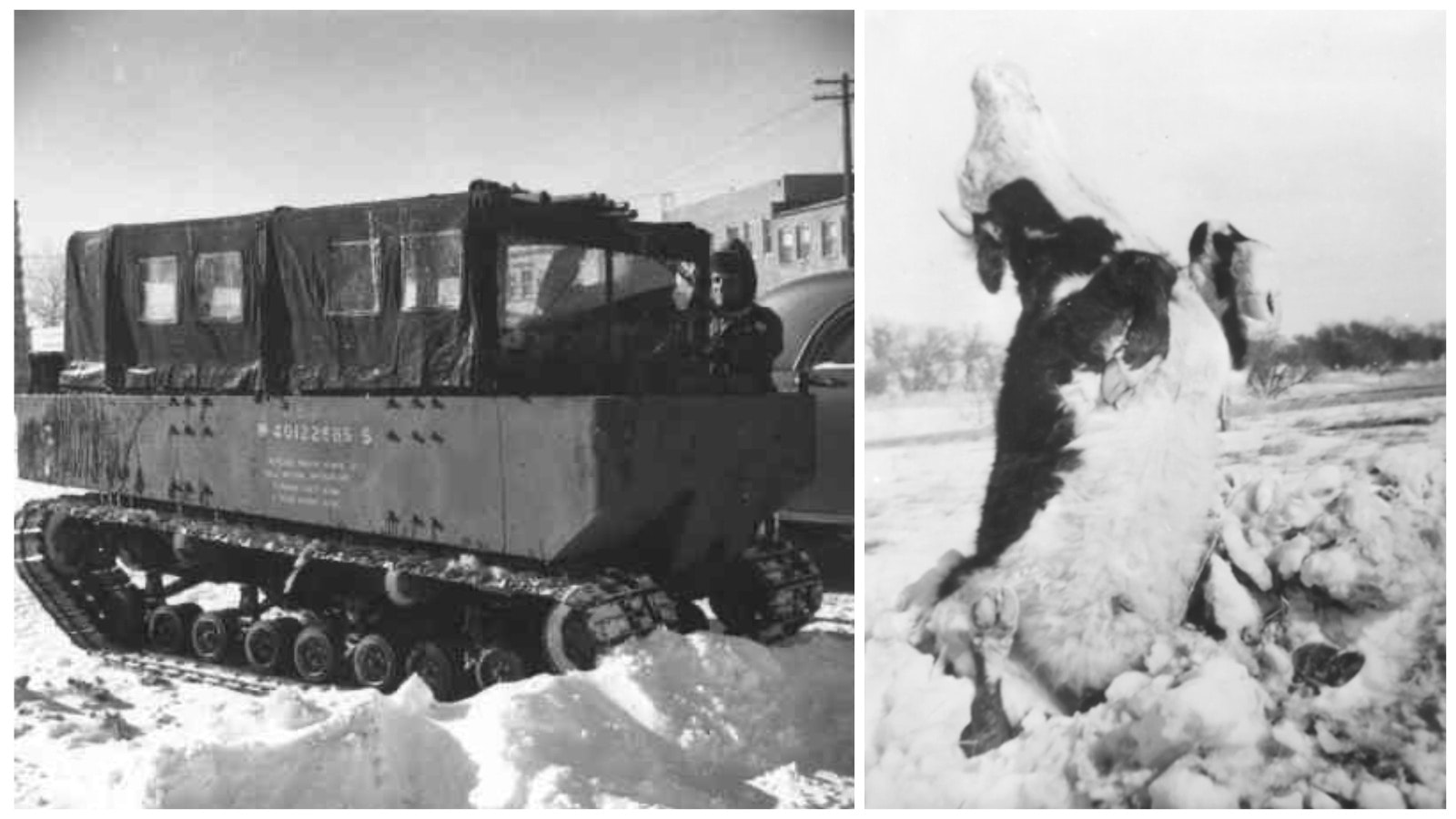

Anything and everything that could be operated in snow was employed for rescue missions. Tractors, bulldozers, Army M29 cargo carriers known as weasels, and even one Sherman tank was dispatched to Green River to rescue a sick Union Pacific employee from an isolated pumping station.

Operation Haylift

After a couple of weeks of unrelenting snow and wind, the focus shifted to livestock and wildlife.

Operation Haylift began Jan. 28 when the U.S. Air Force flew 550 tons of hay to Casper. Feed was also delivered to other parts of Wyoming, with bales sometimes dropped on the open range as close to stranded cattle as pilots could get it.

An estimated 2 million cattle and sheep received hay from the air.

Undoubtedly, many livestock were saved by such efforts. But many more perished.

A survey of about 1,000 farmers and ranchers, completed in early June 1949 reported heavy livestock losses for the hardest hit counties: Fremont, Sweetwater, Carbon, Natrona, Johnson, Campbell, Crook, Weston, Converse, Goshen, Albany, Laramie, Niobrara and Platte.

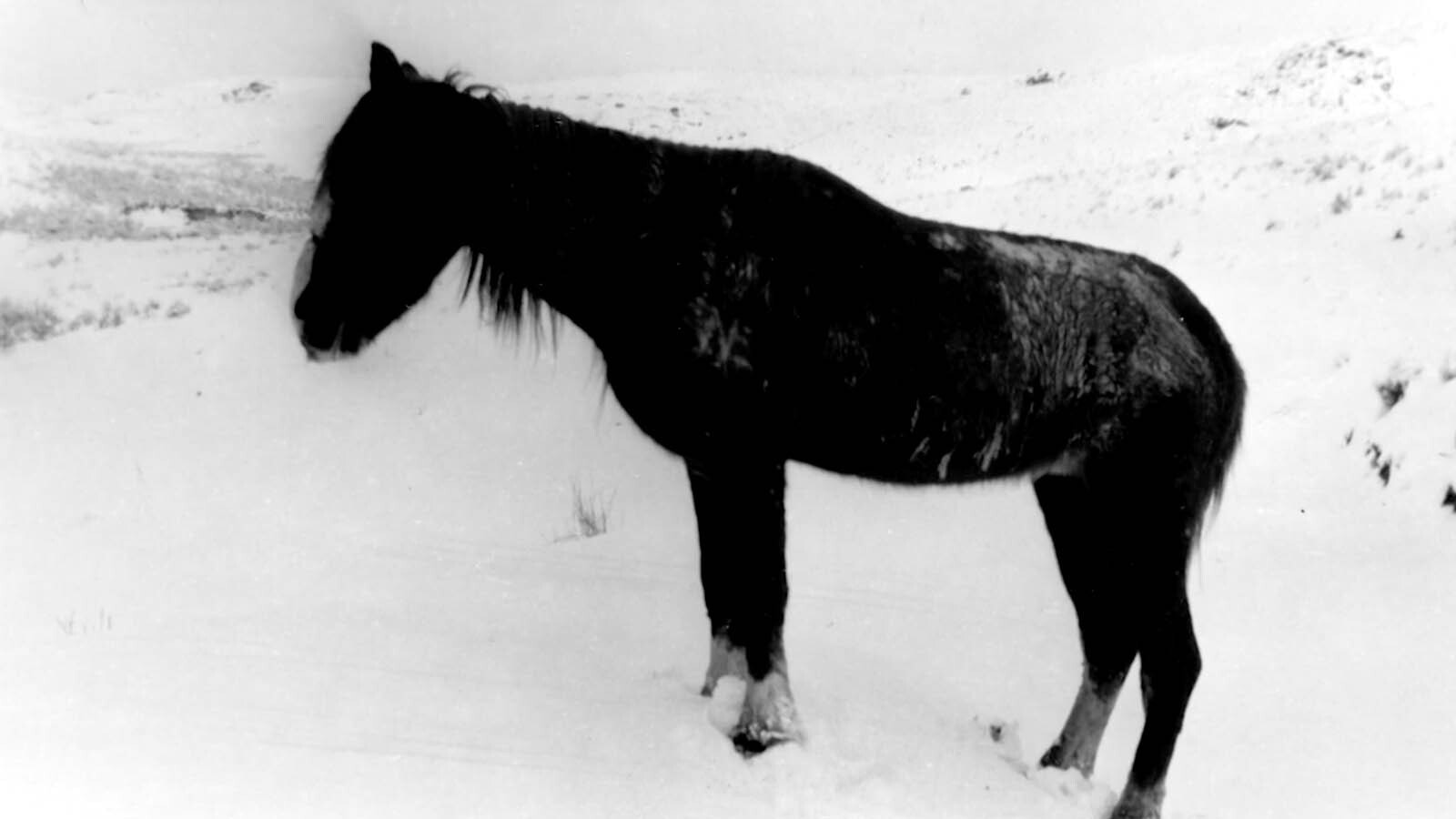

Total cattle loss to the Blizzard of ’49 was estimated to be 55,000 head. Sheep loss was pegged at about 150,000. Most stockmen put that estimate way too low.

The loss and suffering was sometimes too gruesome to witness. Cattle were welded to the ground, frozen in place. Dead on their feet. Horses were found later stiff as a board, standing upright as if merely sleeping.

Sheep, particularly, would panic at a fence line and stand atop one another until they stacked 6 or 7 high and suffocated those below.

Even the animals that survived the initial onslaught later had to be put down because their feet and legs were too badly frostbitten. In some cases, milk cows’ teats and bulls’ testicles froze off.

“We lost our whole herd,” recalled Alice Kimball, who was 21 at the time and ranched with her husband near Glenrock.

There were also astonishing tales of survival.

In one instance, a rancher was certain he had lost his whole flock of sheep, only to discover them days later in his haystack where they burrowed themselves for protection.

Pigs were particularly adept at staying alive.

Bill Fraser, a Pine Bluffs resident at the time, reported that three months after the storm a farmer near Albin dug a hog out of a snowbank still alive.

The snowstorm was also hard on wildlife.

December 1948 was tougher than usual with cold temps and lots of snow. Wildlife was in depleted condition going into January.

The Wyoming Game and Fish Department began emergency feeding of deer, elk and antelope early in January and continued through early March. About 21,000 animals were given hay, cottonseed cake and alfalfa pellets.

State emergency feeding failed, however, to save many deer. Mortality rate was high. Pheasants were also nearly wiped out.

Antelope fared the worst. The Red Desert herd was all but annihilated. An estimated 1,800 antelope were killed on the Union Pacific mainline from trains alone.

Only elk made it through the winter without significant loss.

Operation Snowbound

The federal relief effort hit high gear in late January and early February. Operation Snowbound used some 1,645 pieces of heavy equipment and a 6,000-man workforce at its peak.

Several branches of the military worked in unison with state and local authorities across a four-state theatre of operation with a total square mileage the size of Spain.

In the end, more than 4 million cattle were saved and 243,780 snowbound people rescued. An estimated 115,138 miles of road was cleared by a whopping 18,000 machine hours and a whole lot of backbreaking shoveling.

More than 4,000 people in Wyoming received federal aid. More than 1,000 ranches were assisted in some fashion.

The economic impact of the catastrophe to the state was estimated at $9 million, with a total cost of $190 million to Wyoming alone.

By Feb. 19, the last of the great storms had rolled through and weather began to improve. Mercifully, the spring thaw was a gradual one so flooding was not an issue. In fact, it was a gloriously green spring, a productive summer, and a bountiful fall in 1949 across the state.

Still today, friendly tavern arguments persist over which was truly the worst winter or blizzard ever in Wyoming.

Crummer says there is no doubt in his mind.

“The temperature hovered around daytime highs like 25 to 30 below zero. I saw it the coldest that winter that I have ever seen it in my life. It was 48 below zero,” he said. “Nothing compared to that. We've had winters where we had big storms, but they weren't as big as that, they weren't as cold as that, and they didn't last as long.”

Jake Nichols can be reached at: Jake@CowboyStateDaily.com

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.