When the winter weather in Wyoming gets weird — and when isn’t it weird — the Wyoming Department of Transportation has its own team of snow scientists it can call on.

It’s a group of hands-on scientists whose year-round mission is the practical study and application of science to snow, and more particularly to snow in Wyoming, where wind and cold combine to create some of the most hazardous driving conditions in the nation.

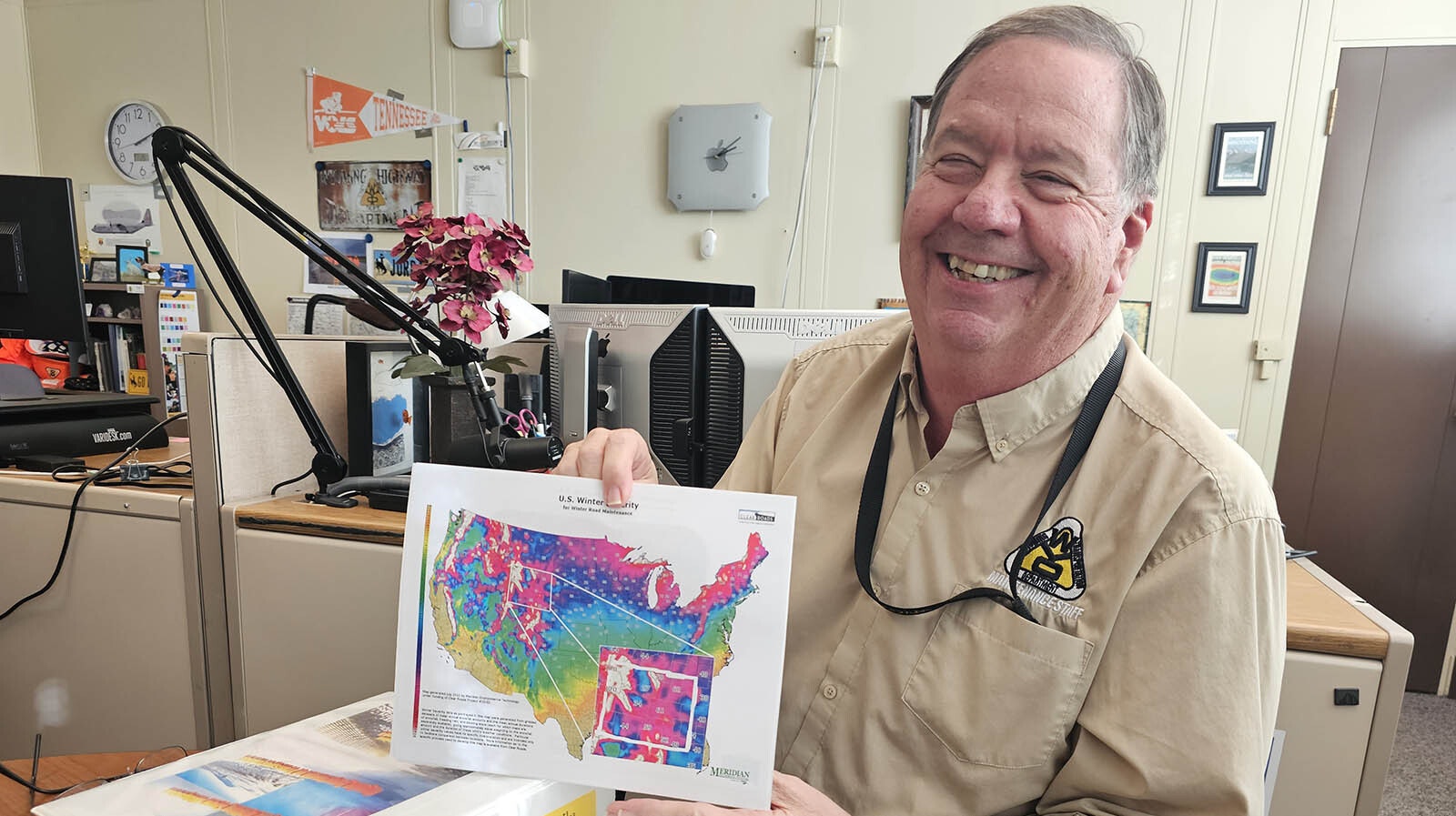

The leader of the team is Clifford Spoonemore, a civil engineer by training. Rounding it out is a geologist and, because this is practical, applied science, a snowplow operator to keep the science real and down to earth.

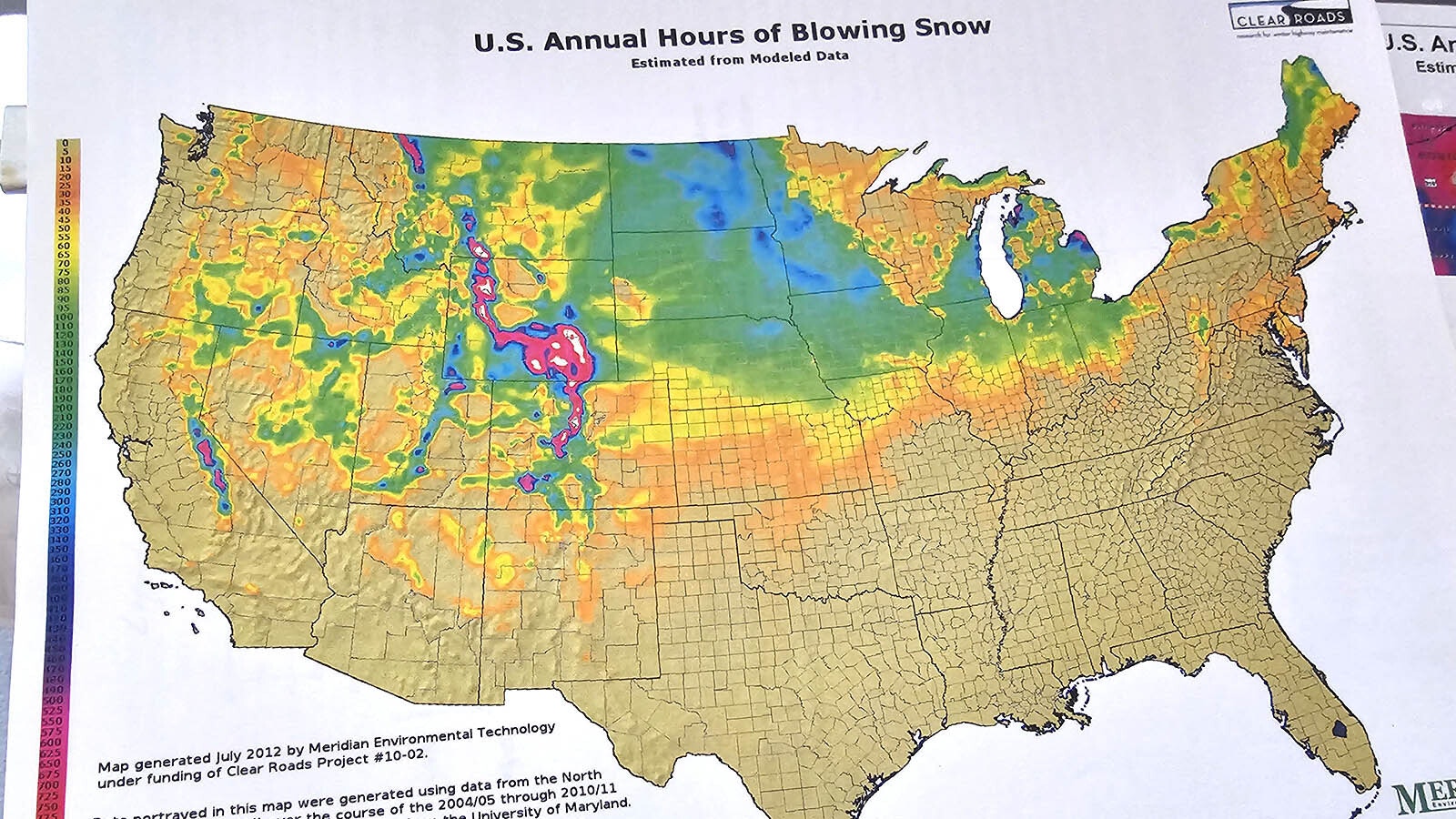

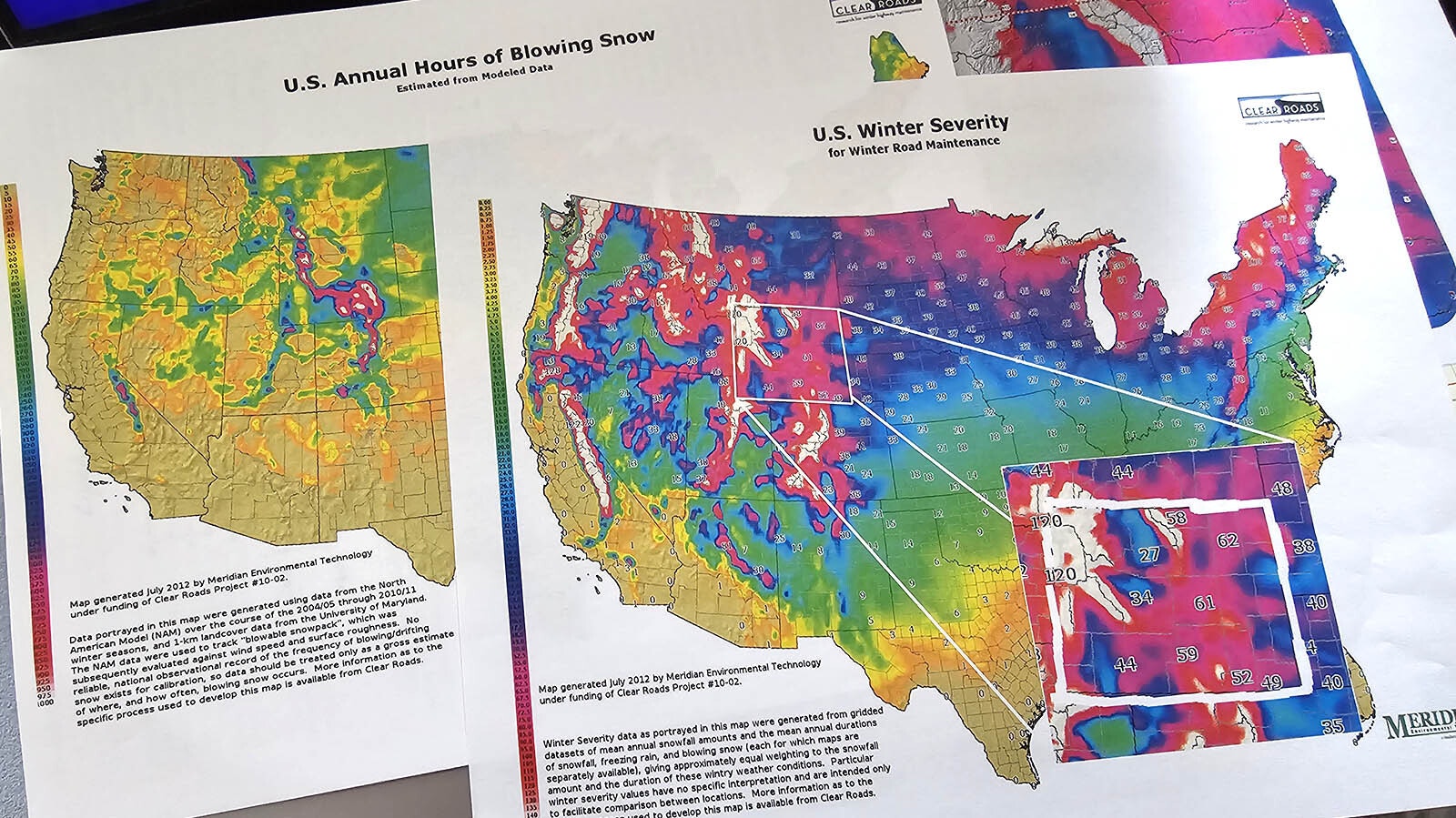

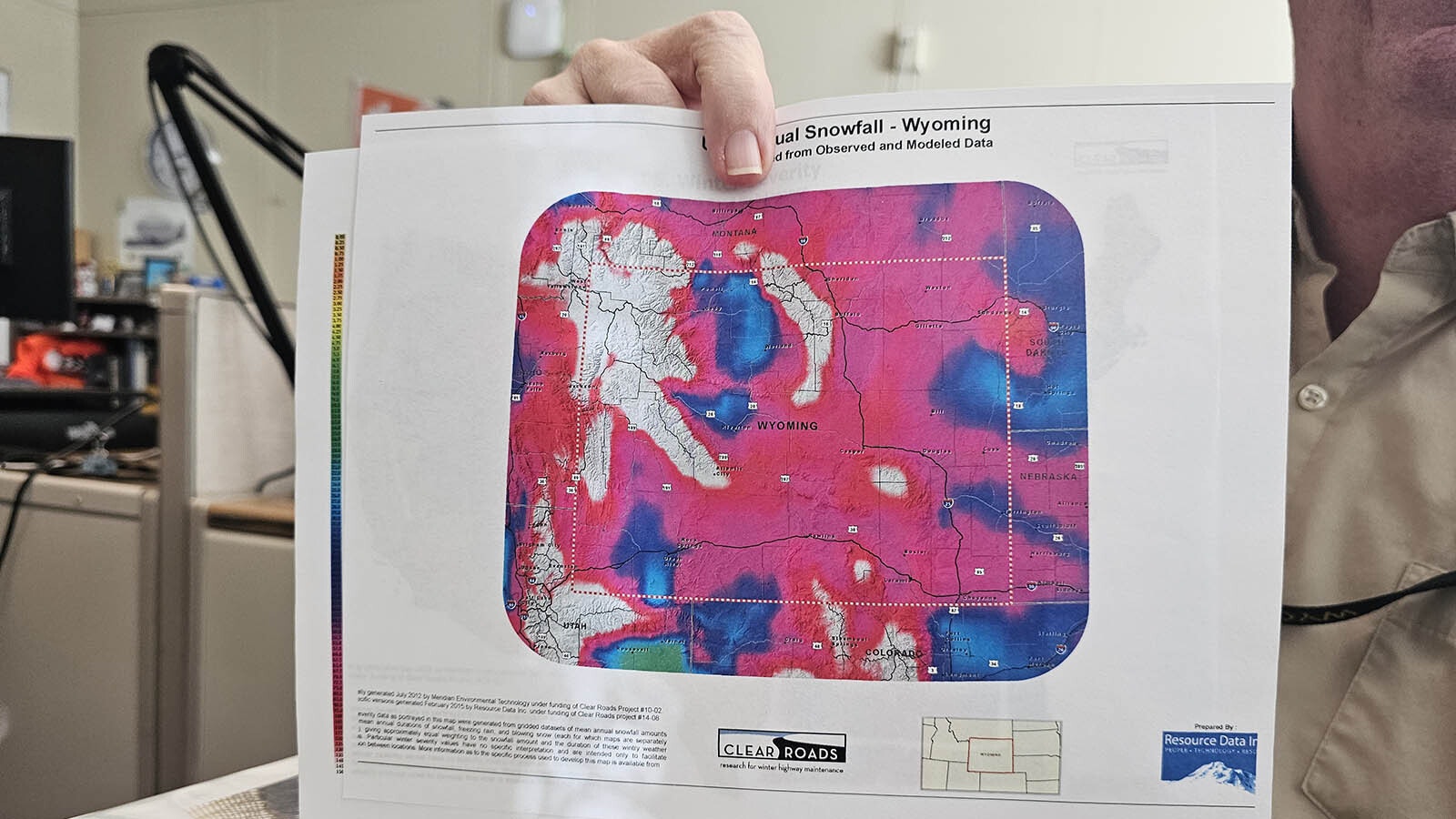

“This is our lovely state of Wyoming inside America,” Spoonmore told Cowboy State Daily as he held up a map showing storm severity across the United States. “And you can see with the scale here, white is the most severe. And, of course, you see (white) over Yellowstone and the Rocky Mountains here, the whole Rocky Mountain chain.”

Meanwhile, the so-called lake effect that should produce bad conditions for Michigan and New York isn’t as severe as one might expect.

“You’d think the lake effect there would be really bad, and it is, but it’s not white like we get,” Spoonemore said.

After pointing out where the snow falls most in Wyoming — the Rendezvous areas, Yellowstone, the Big Horns and Snowy Range — Spoonemore pulls out one more map. It shows the hours of blowing snow on an annual basis for the United States.

“You can see, Wyoming is the epicenter of blowing snow,” he said, pointing to a river a pink that is centered right over the Cowboy State and appears nowhere else in the U.S. “Everybody else gets some snow, and they get wind, but they don’t get both of them like we do.”

Wyoming Is The Eye Of The Storm

Wyoming Department of Transportation has heard often from drivers that it seems as though conditions get remarkably worse as soon as they cross the border into Wyoming.

Maps of snow accumulations and of blowing wind clearly show why. Winter really is much more powerful in Wyoming than in other states.

The challenges that presents have driven the state to take a scientific approach to its snow management that’s a little more dedicated than anywhere else in the nation.

“We are not the only group (across the nation) that was ever formed to do this,” Spoonmore told Cowboy State Daily. “But most states just do it within the internal working order of their table of organization. They don’t break it out into a separate group. We kind of pulled it out separately for, especially because of the special wind that we have.”

The forerunner of WYDOT’s science team was Dr. Ron Tabler. He was commissioned in the early 1960s after Interstate 80 was built to help the state figure out how to keep the highway open more days during winter.

“I-80 was closing 40 days out of 60,” Spoonmore said.

And, it wasn’t even new snow that causing that problem. It was all the dry snow that built up out on the plains, blowing in and closing the road weeks after any snowstorm.

“It might be blue skies in Cheyenne, but out on the interstates, the wind is blowing 60 to 80 mph, and it’s got hundreds of miles of plains full of dry snow and that will just blow across the road when it’s not even snowing,” Wyoming Department of Transportation Communications Director Doug McGee told Cowoby State Daily. “It’s 2-week-old snow, and it’s closing our road.”

Enter The Wyoming Snow Fence

Tabler was with the U.S. Forest Service at the time, studying ways to trap and keep winter moisture around for agricultural use. He had come up with an idea he called a snow fence, which could be placed in desired locations to trap snow.

His idea was that later, when the snow melted, the moisture would seep into the ground slowly, helping create a deeper moisture bank and lusher vegetation.

Wyoming Department of Transportation had a completely different idea for snow fences, however.

They wanted to use the fences to trap all that dry and blowing snow that was shutting down I-80.

Tabler sought out a grant for a 10-year study on when and where to place snow fences to control the blowing snow.

That became his life’s work, much of which is captured in a thick notebook that Spoonmore keeps close at hand.

The Winter Science Team took over Tabler’s work after he retired, to keep improving on the state’s management of blowing snow.

Moving I-80 Isn’t The Solution Some Believe

Many in the Cowboy State have contended since I-80 was built that the interstate should have followed Highway 30 to avoid the worst of wind and blowing snow.

However, maps of what the wind and blowing snow are doing in Wyoming show that moving the route to follow Highway 30 wouldn’t necessarily solve those problems. The route still lies in a giant pink blob where there is more snow and more wind than anywhere else in the nation.

That territory belongs to winter, and it is huge. Going east to west, the blob covers an area that starts right around Cheyenne, just after the edge of I-25. It doesn’t fade at all until sometime after Rawlins, somewhere in the Wamsutter area, and it remains in the next highest level — blue — until Rock Springs.

Going north to south, the blob goes from the Colorado border almost to Casper, stopping just shy of Douglas.

Missing the pink area altogether is impossible.

It’s most narrow across the Colorado border, but moving I-80 there would put the route going over challenging, mountainous terrain in the area of Baggs and Savery, or even further south into Colorado.

“We don’t know that trying to skirt up and go through Medicine Bow would have helped too much. It’s just one of those, we still would have been there,” Spoonmore said, pointing at Highway 30 on the map, with all the pink surrounding it.

400 Miles Of Snow Fences

Wyoming has more than 400 miles of snow fences these days, and just about every aspect of them has been studied, either by Tabler or the snow science team that took over for him.

Studies have looked at optimal locations, whether vertical snow fences are better than horizontal, and the ideal gap between the ground and the snow fence. The most recent study looked at how much energy a solar panel attached to a snow fence collects, and whether the panel harms snow fence efficiency.

The study shows the panel can collect a lot of energy, without appreciably harming the ability to capture snow.

WYDOT has no concrete plans to add solar panels to all of its snow fences at this time, but it’s something that may be considered at some point in the future. Power from the solar panels could help run roadside signs and other applications.

Once the science team was established, it didn’t take long to realize there are a lot more questions that the team can tackle for the department to determine what’s optimal for winter weather management.

“Over the years, we’ve learned far more about winter overall, and now we get into almost everything winter,” Spoonmore said.

New studies are looking at things like automated vehicle location devices that can track vehicle locations and measure how much material is being put down in those locations. Another study is examining what color of lights are most visible in a snowstorm to try and prevent crashes involving snowplows.

“We can use drones to fly into our indoor stockpile sheds and take measurements,” Spoonmore said. “And that will save people from having to climb up and take the measurements themselves. They can get all sorts of information using drone technology.”

Why More Salt Isn’t Always The Right Answer

One of the really important questions the team has tackled is when and where to place snow-fighting materials like salt and sand, which the department buys by the ton.

WYDOT used 234,564 tons of sand and salt mixes for the 2022-2023 winter season, 6,044 tons of bulk sodium chloride, just over 1 million gallons of various liquid deicers, and 4,865 tons of other melting compounds.

With a shopping list that large, it pays to be efficient with the materials use, and that’s one of the things the science team works to refine.

In many cases, the answer isn’t necessarily to just put down more material either. There are complications with each material because of Wyoming’s winter conditions.

“We can put down salt, but the issue is dry salt has to go through a phase change (to be effective),” Spoonmore said.

A phase change refers to changing salt from a solid, dry powdery substance that would just blow away to something that is in a liquid form that can stick around long enough to do some good.

Generally, that means having enough natural energy from the sun to melt some of the snow. That helps keep the salts working in a brine at appropriate and effective concentration.

Temperature Places A Hard Limit On Salt Use

But salts have their limits temperature-wise, and that’s a complicating factor. They just won’t work below a certain range.

For sodium chloride, that outer limit is minus 6. But it works far better between 16 and 28 degrees. That gives a window for the snow to melt enough that a snowplow can come through and get it off the roadway.

Magnesium chloride, meanwhile, has a little bit lower effective temperatures. Its outer limit is minus 28.

But, like sodium chloride, its effective window is much higher. Its optimal range is between zero and 20 degrees.

Other materials that go further down the temperature scale are possible, but too expensive for widespread application and, in some cases, highly hazardous substances. Wyoming doesn’t use them for those reasons.

Putting salt down when conditions aren’t optimal has its dangers, and can actually be counterproductive to road safety. The salts have to be applied wet, so that wind doesn’t just blow it all away before it can be of use, as well as to ensure the brine has an optimal salt concentration.

“Any time you put down a chemical — go back to our wind,” Spoonmore said. “It is above 50 mph. All you’re doing is making your road wet and giving a spot for that snow to stick, and then it becomes your problem instead of your solution.”

Sand, meanwhile, is generally used as a means of adding more traction to the roads. It is vulnerable to both high wind and passing trucks, which blow it right off to the side of the road.

Renee Jean can be reached at: Renee@CowboyStateDaily.com