There’s a new Loch Ness Monster in Wyoming, and it’s adorably tiny with puppy-dog eyes.

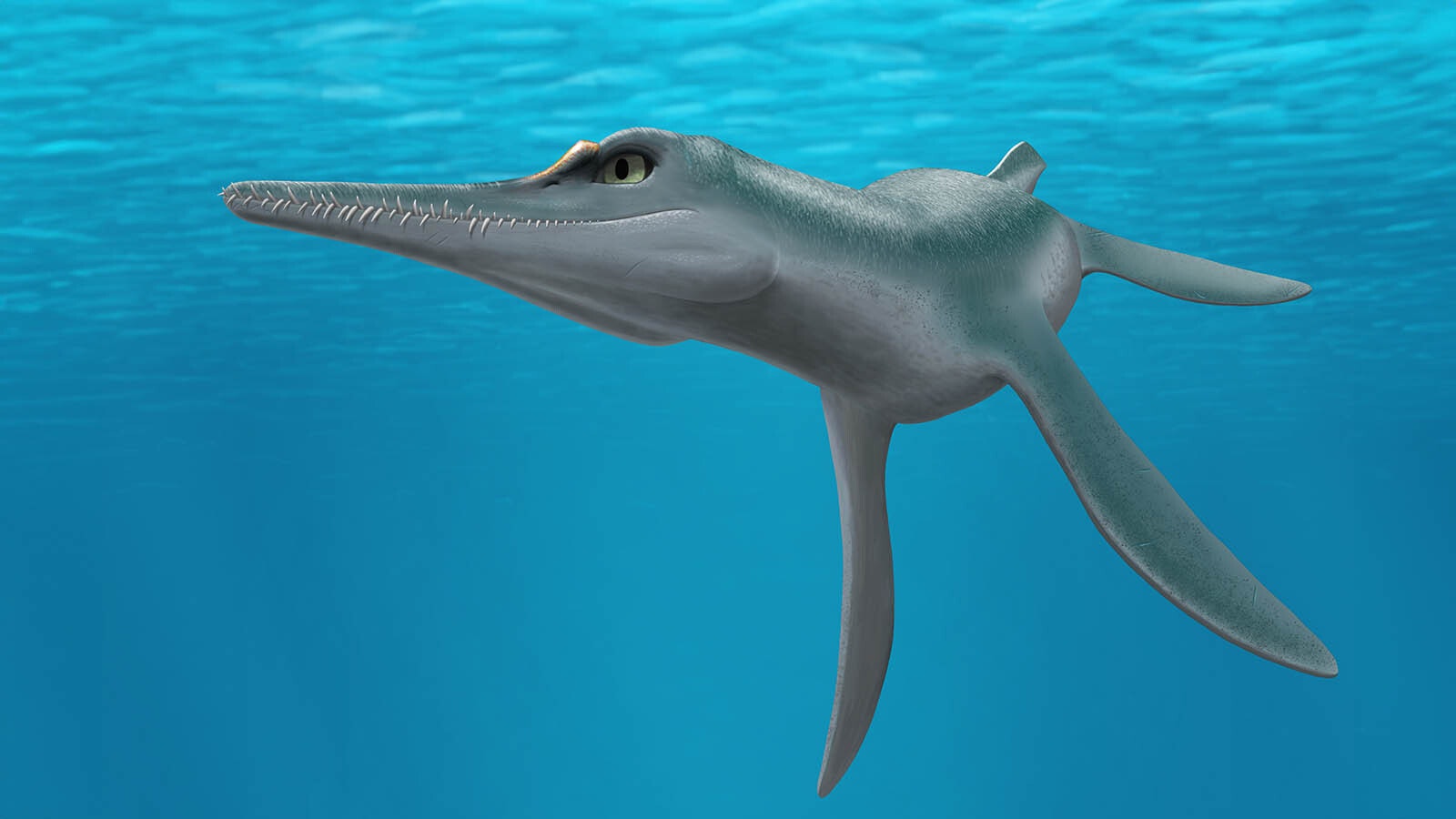

Unktaheela is the newest type of prehistoric marine reptile identified from the Late Cretaceous rocks of Wyoming, but it’s the proportions of this plesiosaur that make it unique.

“With its small body size and huge eyes, Unktaheela kind of looks like a baby,” said Robert Clark with the Department of Biological Resources at Marshall University in West Virginia. “That’s what baby vertebrate animals look like: little and cute, with big puppy eyes. And Unktaheela was a super cute little polycotylid.”

Pretty Plesiosaurs

While dinosaurs dominated land, plesiosaurs were abundant in the prehistoric seas during the Mesozoic Era. The most famous plesiosaur is Kansas’s Elasmosaurus, which had a 23-foot neck with 72 vertebrae.

“Among nonscientists, plesiosaurs are mostly known for being huge and having long necks,” Clark said. “But there were also medium-sized and small plesiosaurs, and many of them had shorter necks. And that’s where polycotylids come in.”

Polycotylids are a family of plesiosaurs that tend to be smaller, with short necks, large heads and especially large flippers. Unlike their long-necked relatives, polycotylids were agile swimmers that chased fish and other small marine critters, catching them with long, narrow snouts with conical teeth.

The fossils of Wyoming’s newest polycotylid were found in 1975. A field crew from the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History excavated the fossils from the 80 million-year-old Sharon Springs Formation in Niobrara County.

Clark, one of the authors of the new scientific paper, “rediscovered” those fossils in the university’s basement. They conclude that there are plenty of plesiosaurs in the stone seas of the Cowboy State.

Eyes On Unktaheela

There are dozens of different polycotylids from the Late Cretaceous. But even in a family of short, stumpy sea lizards, Unktaheela is unique.

“It’s the smallest known polycotylid at only about 7 and a half feet long,” Clark said. “It also has proportionally larger eyes, a wider skull, an especially narrow snout and a shorter back of the skull than any other polycotylid. And it has at least a dozen distinctive characteristics that make it different from everybody else.”

A 7-foot-long adult Unktaheela would look more like a meal than a relative of the nearly 40-foot-long Elasmosaurus. Even amongst other polycotylids from the same time and place, Wyoming’s newest Loch Ness Monster makes a big impression with its small size.

But it’s the eyes of Unktaheela that are especially eye-catching for paleontologists. The bone structure of its skull is similar to the skulls of eagles and other birds of prey, suggesting that the unrelated animals saw the world and hunted in similar ways.

“Both have forward-angled eyes for binocular vision, a narrow snout affording a clear forward view, and a large, flat, bony ledge over each eye,” he said. “Bony ledges over the eyes of eagles have been shown to shade their eyes from the sun’s glare as they search for prey. We think the ledges over the eyes of Unktaheela may have shaded its eyes as it hunted in sunlit habitats just below the water’s surface.”

With its eagle eyes and puny physique, Unktaheela swam the warm waters of the Western Interior Seaway, an inland sea with different environments than the open ocean. It would’ve shared its world with other Wyoming polycotylids, like Dolichorhynchops and Serpentisuchops (a relatively new species found near Glenrock).

“North America was split into eastern and western landmasses in the Late Cretaceous by the Western Interior Seaway, which ran from Canada to Mexico and over the midwestern United States,” Clark said. “Unktaheela patrolled the Western Interior Seaway with other plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, sea turtles and sharks.”

An Unknown Adult

Clark has been studying plesiosaurs at Marshall University with Dr. F. Robin O’Keefe, a renowned expert on plesiosaurs. The research that led to Unktaheela started in 2019 when the adult polycotylid was still masquerading as a child in the basement of the University of Colorado Natural History Museum.

“There was a paper published in the ’90s that described one of the Unktaheela skulls as being a baby of another genus,” he said. “But we’re confident that both Unktaheela specimens are adults.”

Based on these fossils and a second specimen found in South Dakota, Clark and his colleagues determined that Unktaheela was too well-developed to be a young animal. It has too many teeth, its bones are fused (which is interpreted as a sign of old age in many animals), and the bones in its large flippers have lost their youthful smoothness.

When giving their discovery a new name, Clark said the eyes inspired a name from the mythology of the indigenous people who shared a home with the plesiosaur (although their residencies were 80 million years apart). The bony ledges above Unktaheela’s eyes reminded the paleontologists of a mythological monster.

“Plesiosaurs are a bit like sea serpents,” he said. “We chose to name it Unktaheela to pay homage to the keen-eyed, horned water serpent of the Native American Lakota people who lived in South Dakota and Wyoming close to where the fossils were unearthed.”

The eyes of Unktaheela helped Clark and his colleagues see a new polycotylid perspective. Clark believes many more monsters are waiting to be unearthed in Wyoming’s ancient seas, and they’ll add their mythology to the complex science of paleontology.

“Wyoming is an important state for polycotylid paleontology,” he said, “and there’s undoubtedly much more to discover.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.