In more than 40 years of caving, Juan Laden has plumbed the depths of live caves in New Zealand, Europe, Antarctica and Mexico, dropping as deep as 700 feet below the surface of the earth to see the wonders that lie hidden in a world far, far beneath our feet.

In Mexico, that’s included the amazing caves in Quintana Roo, while in New Zealand it led him through caves with ice so blue it’s like the sky, and then through the fossilized backbone of a whale.

“We were sideways in this oscillation, and you get into kind of a rhythm,” Laden told Cowboy State Daily. “And then you come around this bend, and there you see these giant vertebrae in the side of the cave.”

A couple of fossilized rib bones then came into view, along with a dawning sense of wonder at the realization that Laden was walking through the remains of a prehistoric whale that would have lived eons ago.

“When you’re caving, it’s not just backpacking in the Winds or something,” he said. “You’re actually in the earth, and so there is this really amazing sensation of communion with nature and the universe.”

But of all the cool caves he’s ever visited, one that is particularly high on Laden’s short list of coolest caves is right here in the Cowboy State.

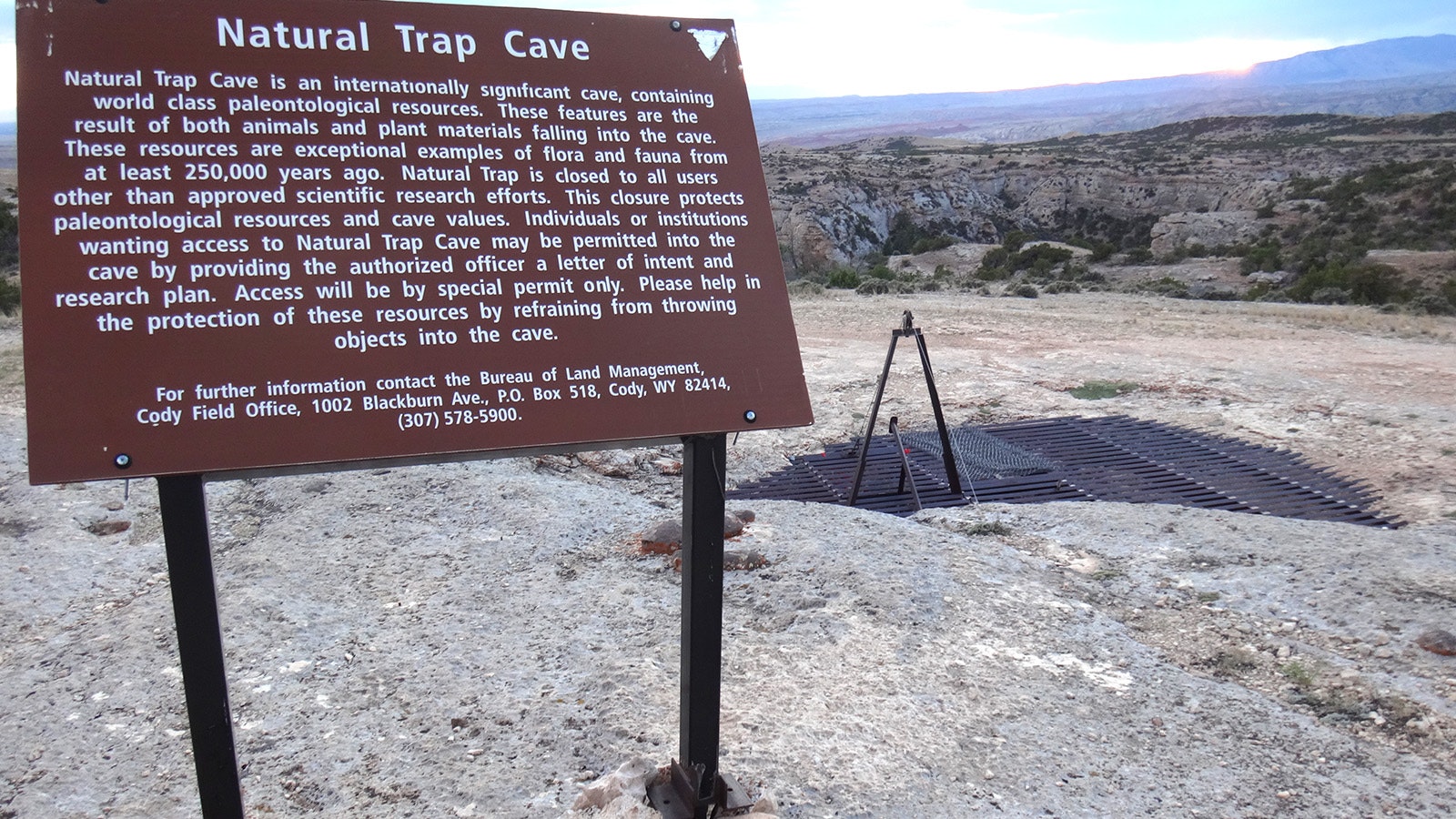

It’s called the Natural Trap Cave, and it has been hiding for a quarter million years or more along a main wildlife corridor in the northern Big Horns in Wyoming just below the border of Montana.

Archeological Treasure Chest

The entrance to Natural Trap Cave is a 15-foot-hole that can’t be seen until it’s well past too late for any hapless creature stumbling upon it, regardless of whether it’s nighttime or broad daylight.

“It’s a very natural traveling path for a lot of animals,” Laden told Cowboy State Daily. “Typically, if animals are trying to escape predators, they’re going to run downhill as opposed to uphill. So, they’re running down the ridge, and just before the hole, there’s a little drop-off. So, you can’t see the hole until you’re on this little slopey edge, and then you’re in the hole.”

From the treacherous “slopey” edge, it’s an 80-foot drop straight to the ground — an instant killing blow for all but the smallest of creatures.

So far, researchers have found bones from giant bears, mammoths, camels and prehistoric horses lying on the floor of Natural Trap Cave. There are also giant lemmings, cheetah, American lions and wolves, as well as a range of microfossils — among them pollen — all of which could help researchers completely flesh out the ecosystem of a long-lost Wyoming world.

Laden, who lives in the Lander area, has been helping researchers access Natural Trap Cave since 2014. He will be talking about that work and his other caving adventures soon at an upcoming presentation set for 6 p.m. Jan. 18 at the Dubois Museum.

Perfectly Preserved

The humidity and temperature in Natural Trap Cave are nearly perfect for the natural preservation of bones.

The cave is about 42 degrees year-round, so a bit like a refrigerator even on the hottest summer day. And it’s just dry enough that things don’t readily rot. But it’s not so dry that everything just becomes a pile of meaningless dust.

The only other places in the world with this kind of high-quality preservation are Siberia and the Arctic, making Wyoming’s Natural Trap Cave a world-class resource with international significance.

“It’s just kind of a perfect, or very good situation for preserving bones,” Laden said. “And because of that, they’re getting mitochondrial DNA out that’s, like, 20,000 years old.”

Using new genetics techniques, that mitochondrial DNA is opening a new window on the lives of North America’s Ice Age animals.

Among the more recent discoveries is evidence that Beringian wolves might actually have been present in what is today the Lower 48 states of America.

Until now, it wasn’t thought their range extended down so far in North America.

“One of the researchers, Julie Meachen, did a comparative anatomy on all the wolf jaw bones,” Laden said. “And she claims that these jaw bones are not gray wolf or dire wolves. They could actually be Berengian wolves, which had a more robust lower jaw for breaking bigger bones.”

Meet Packey Le Pew

During the Ice Age, large glaciers covered most of the land north of what is today Wyoming. These huge sheets sometimes expanded, sometimes contracted, depending on the climate of any given year.

It’s thought that they provided a gateway for animals, and eventually people, to pass between North America and Europe or Asia.

Some researchers, including Meachen, have suggested that the Big Horns might have been the gateway, with Natural Trap Cave smack in the middle.

Meachen hopes to learn more by looking at the teeth of large mammals, which could tell what they were eating, and what the water cycles were like at the time they died.

That in turn could lead to new insights into what exactly killed off all the megafauna at the end of the Ice Age 20,000 or so years ago.

“One theory is that humans came over, you know, sometime 20,000 years ago or so — it used to be 10,000 but now it’s getting pushed back to possibly mid-20s — but that humans came over, and these animals had no idea that these humans, these tiny little things, are so dangerous, and the humans killed them all off,” Laden said.

Another theory, though, is that the megafauna died off due to sudden climate change, or perhaps a combination of both factors was in play.

“There’s other factors we may not know about that we may find there too,” Laden said. “And (the scientists) go back every year, and they’re doing pilot sedimentary studies, and they’re looking at all kinds of micro fossils, paleontological anatomy and DNA studies.”

In addition, other researchers have studies that are piggybacking the effort.

For example, herpetologists have been to the location after a rare sighting of a rubber boa snake, while an unfortunate pack rat that fell into the hole and instantly died has been turned into a study on how the creatures that fell into Natural Trap Cave desiccate and deteriorate over time.

“He became a taphonomy study, which is the study of how organisms deteriorate,” Laden said. “And so we put a little cage around him and he got named Packey Le Pew.”

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.