CASPER -— Call Wyoming the pilgrim way, because it rarely was the destination. The territory was just an interesting place to pass through.

Before white settlers came through what is now Wyoming, the Sioux, Arapaho, Shoshone and other tribes left their trails — many passing through.

In 1812, Robert Stuart was on his way from Oregon when he discovered the South Pass, set up a temporary cabin to winter in and then headed east.

In later years, other explorers passing through made maps.

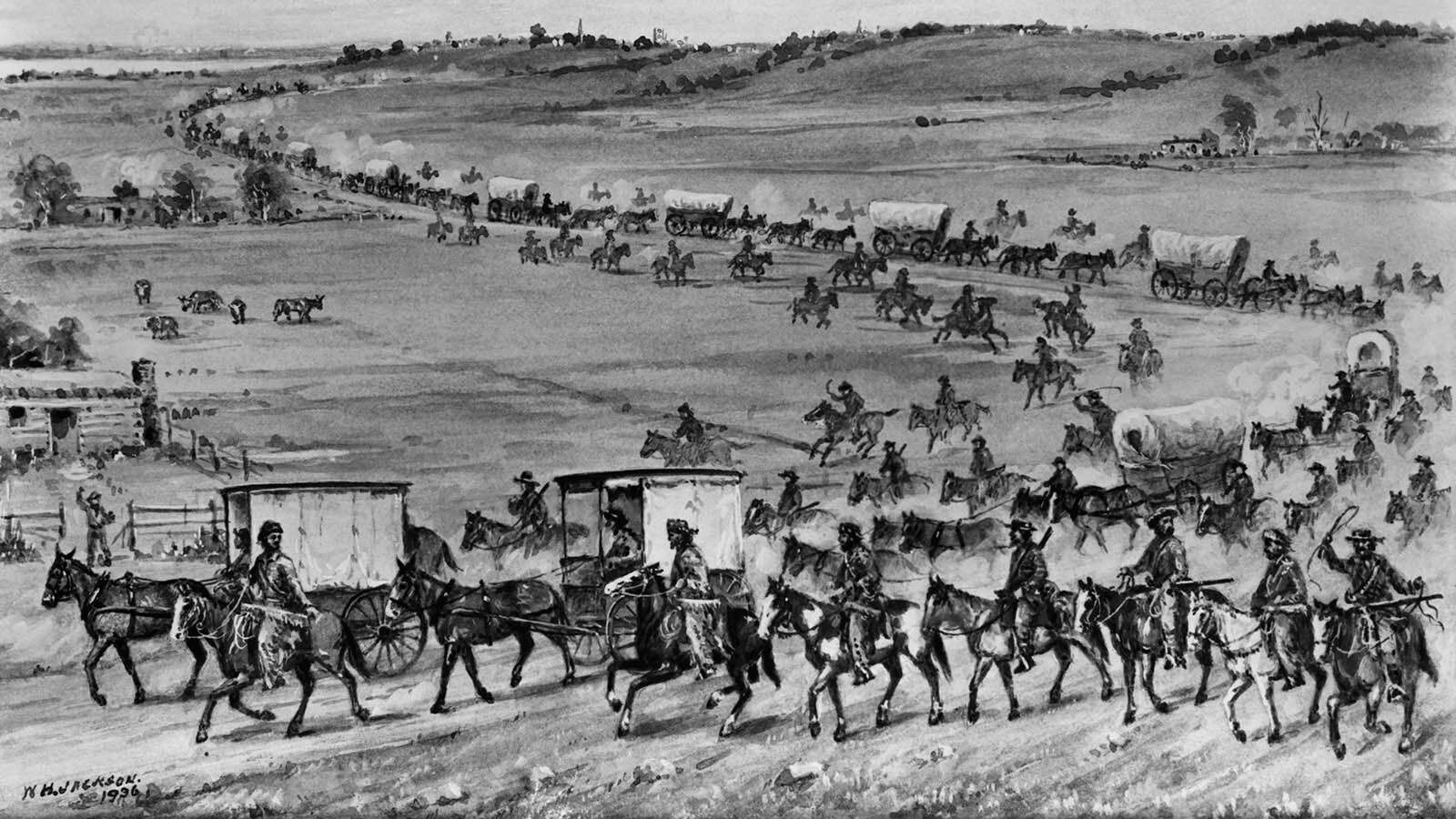

That led to more people finding and expanding upon native trails as they headed to Oregon for its fertile soil, Salt Lake City for its haven for Mormons, California for its gold and Pony Express riders for their mission as the first cross-nation, long-range couriers.

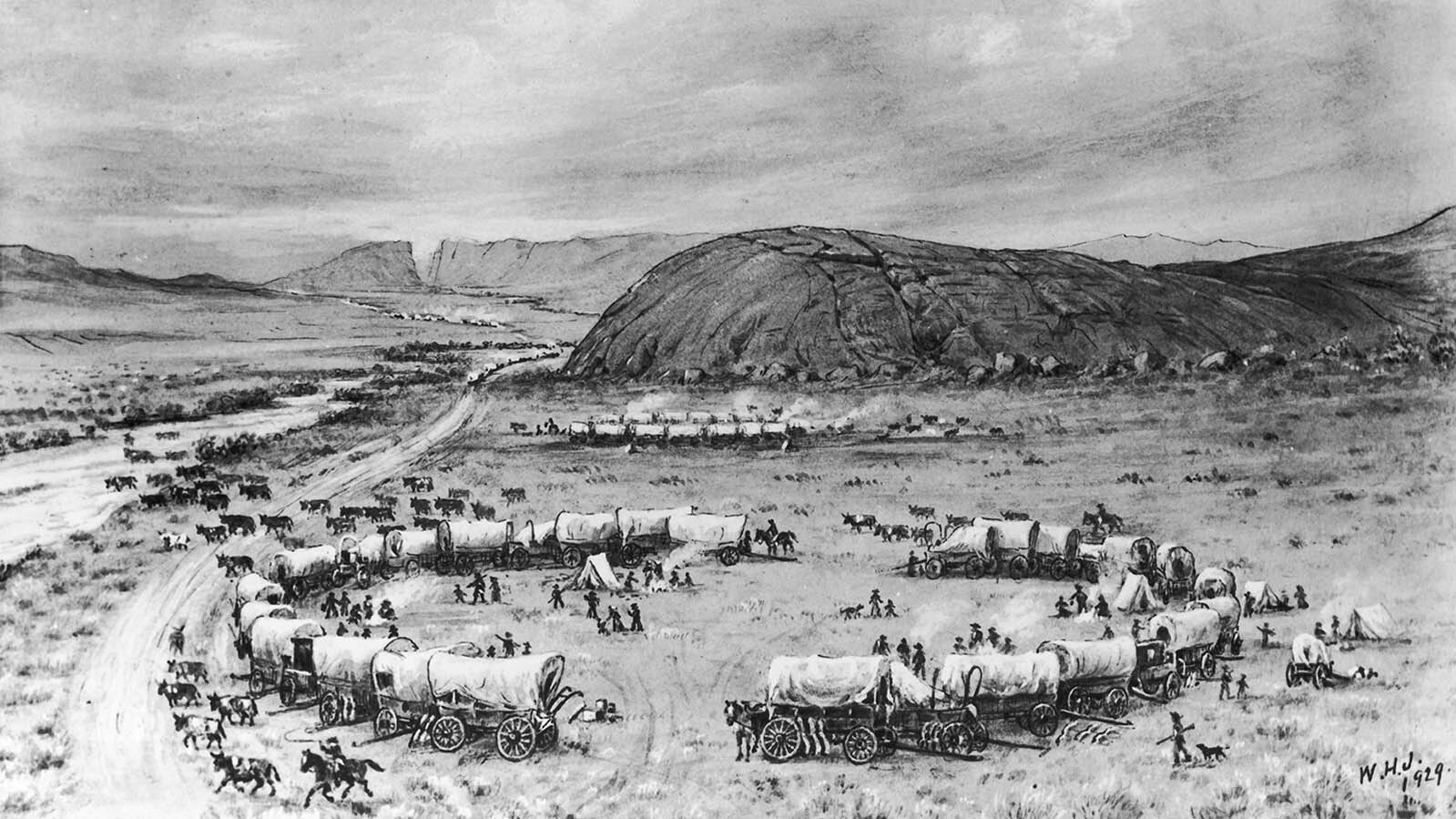

The legacy of the historic California, Oregon and Mormon trails — and others — blazed through Wyoming is carved into the Cowboys State by the wagon ruts of pioneer pilgrims who passed through by the thousands, and died by the thousands.

Most Trails Touched Casper Region

Many of those travelers’ footsteps, wagon tracks and hoofprints made their marks in the soil around Casper. So, the city is a fitting place to give those travelers their due.

At the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper, visitors get a taste of what it was like to cross the Platte River on a wagon, learn about Mormons using handcarts to make it to their promised land in Salt Lake City, and understand the impact of the California Gold Rush and other gold fever that led to conflict with indigenous tribes.

Interpretive Center Visitor Information Specialist Reid Miller and his colleague, Jason Vlcan, see their role as helping visitors experience a sense of the hardship and context of those who would have passed by more than 150 years ago.

“I represent the stories of the migrations,” Miller said.

And the stories are interesting. The video “Footsteps to the West” shares the words from letters and diaries of those who jolted in the ruts and walked along the plains in hope of a better future.

- “The same thing over, and over again …”

- “The Platte had become familiar to us having come along its banks and within sight of it for 500 miles.”

- “This is a good cause worth living for, wherever we go we find opportunities to do good. If we had packed one or two animals with Bibles or Testaments we should have had enough to dispose of there with trappers and traders in the mountains.”

Many Graves, Known And Unknown

Wyoming today remains the most unsettled state in the nation in terms of population, but it is also one of the most passed through. While only a hardy few put down roots here, a lot pass through on their way east and west.

And it may be that the state that contains the most remains of those among the 500,000 people from 1840 to 1869 who failed to reach their destinations. Dysentery cholera, accidents and battles are all part of the stories of those pioneers.

An account written by the daughter of Luzena Stanley Wilson, who left Missouri headed for California in 1849 with her husband and two children, can be found at the Library of Congress. She shares her first experience with death and a burial along the California trail that passed through what is now Wyoming.

“We were sitting by the campfire, eating breakfast when I saw two digging and watched them with interest never dreaming of their melancholy object until I saw them bear from their tent the body of their comrade, wrapped in a soiled gray blanket and lay it on the ground,” she wrote. “Ten minutes later the soil was filled in, and in a short half hour the caravan moved on, leaving the lonely stranger asleep in the silent wilderness …

“Many an unmarked grave lies by the old emigrant road, for hard work and privation made wild ravages in the ranks of the pioneers and brave souls gave up the battle and lie there forgotten, with not even a stone to note the spot where they sleep.”

A Diary Of Dates And Graves

A page from the book “Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey” includes part of the diary of Cecelia McMille Adams, who took a wagon train from Illinois to Oregon in 1852 and kept track of the dates and the graves she passed, a grim timeline of death along her pioneer journey.

“June 25, passed seven graves,” she wrote. “June 26, passed eight graves; June 29 passed 10 graves; June 30, passed 10 graves, made 22 miles; July 1, passed eight graves, made 21 miles; July 2, one man of (our) company died. Passed eight graves, made 16 miles.”

Historians say the goal of wagon trains was to be at Independence Rock, in what’s now southwest Natrona County in Wyoming, by July 4, indicating the possibility that all those June deaths were in what is now Wyoming. And her account from July 2 to the end of July — 64 graves, 162 miles — indicates those deaths were also likely in Wyoming.

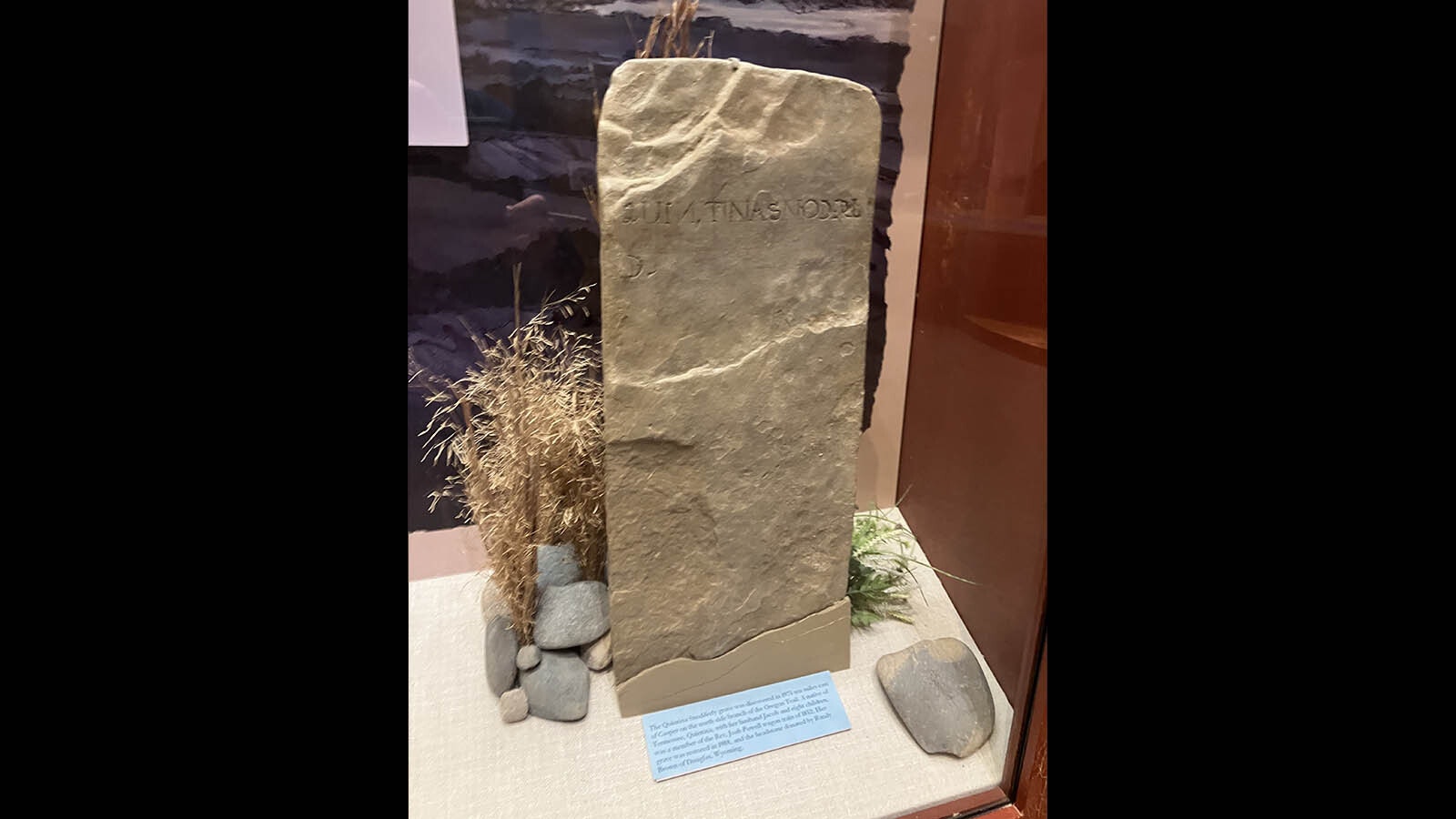

One Interpretive Center display shows visitors the actual headstone of a Quintina Snodderly. Her grave was discovered in 1975, 10 miles east of Casper on the north side branch of the Oregon Trail. Along with her husband Jacob and eight children, she was a member of the Rev. Joab Powell’s wagon train of 1852.

Vlcan said there are about 75 graves in Wyoming that have been identified as those who were on various wagon trains. Historians estimate 25,000 to 30,000 deaths happened along the trails between 1842 and 1859. During spring and summer, the center leads expeditions on the trail and to known gravesites.

Crossing The Platte

As part of the pioneer-pilgrim experience, the Interpretive Center offers visitors an opportunity to get in a covered wagon and understand how uncomfortable and scary it was to cross the Platte River in one back in the day.

On the day Cowboy State Daily was at the center, Miller invited visitors to step inside the wagon and take and seat while a video at the front opening of the wagon depicted the wagon master directing it across. Once in the middle of the river, another wagon in front starts drifting away.

The wagon jars from side to side, simulating the rutted and rocky crossing to the north side. One family enjoyed the lesson that day.

“It was fun. What a hardship the whole thing was,” said Marcia Rice of southeast Pennsylvania, who “traveled” the bumpy river crossing with Neal Martorelli, his wife Cora and little son, Benjamin.

An actual account of the crossing by Luzena Wilson at the Library of Congress conveys how dangerous crossing the North Platte River was without the dams that are there today to tame the river.

She characterized it as a “boiling, seething, turbulent stream, which formed and whirled as if enraged at the imprisoning banks.”

“Two days we spent at its edge, devising ways and mean. Finally, huge sycamore trees were felled and pinned with wooden pins into the semblance of a raft, on which we were floated across where an eddy in the current touched the opposite banks,” Wilson wrote.

The Interpretive Center also shares the account from the Mormon Trail that began with the first group in 1847 led by Brigham Young. The members of the fledgling church created an immigrants’ guide that provided useful information to all travelers, not just Mormons.

‘Handcart Mormons’

One display features a story of the “Handcart Mormons” in 1856, who got off to a late start from back East. Instead of oxen or horses, they used their own power to push handcarts with their possessions.

They were hit Oct. 23 with a snowstorm near Red Buttes west of what is now Casper and quickly found themselves in trouble. Brigham Young sent a rescue party from Salt Lake. They were able to rescue 622 of the pioneers, but 150 still died.

The California Gold Rush brought many more travelers through the trails, and the discovery of gold in Montana led to the Bozeman and Bridger trails heading north out of the region. Those trails broke treaties and led to conflict with the native tribes, most notably Red Cloud’s War.

The Pony Express, which only lasted less than two years, saw 80 young riders on the trail between St. Joseph, Missouri ,and Sacramento, California, in 1860 on fast horses galloping across the state to take mail to the West Coast and back. The experiment by the Russell, Majors & Wadell Co. was eclipsed by installation of the transcontinental telegraph in 1861.

Trails To Railroad

By 1869, the transcontinental railroad was in place and the use of the trails dwindled as a means to get to the West Coast. But some travelers were still passing through.

Miller at the Interpretive Center said the railway explorations and mapping funded by Congress a couple decades earlier led to the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862. The Civil War delayed its construction.

Some of those who passed through returned to establish homesteads and “dabble in mining and growing livestock,” Miller said. Surveys by the federal government on public lands showed the “highest and best” use of Wyoming territory was for grazing.

That led to federal legislation favorable to stock growers and the ranches and industry that remains a vital part of the state today.

But the transiting did not stop.

The Union Pacific rail corridor would become the visual path for the fledgling air mail industry across the state in 1918 before there were navigation instruments and in later decades that rail corridor would lead to the development of the Lincoln Highway, which evolved into Interstate 80.

“Wyoming has been a place that people transit through for a long time,” Miller said.

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.