Kindergarten and first grade students from Jackson Hole Classical Academy (JHCA) enjoy an annual sleigh ride on the National Elk Refuge. Most have spent their first six, seven or eight years in Jackson, so elk are nothing new. For them, it’s kind of like a busman’s holiday.

The sleigh rides are operated by Double H Bar — a family operation that’s been the refuge concessionaire since 2007. They also run the popular Bar T 5 Covered Wagon Cookout every summer.

The HH owns about 20 teams and all types of wagons. They were recently renewed for another five-year contract, so they’ll be on the job in the Elk Refuge until at least 2028.

These teamsters do more than drive your sleigh. They are very knowledgeable about anything to do with elk, the refuge or wildlife in general. In fact, they are quizzed on it before they are allowed to take the reins.

“The educational component is something we take a lot of pride in,” said Double H Bar co-owner Chris Warburton. “From beginning of a sleigh ride to the end, we share fact-based information about the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Elk Refuge, and what they do. We talk about elk and all the other wildlife we encounter on our rides.”

On this particular sunny winter day in early 2023, the students from JHCA peppered their driver with questions that were decidedly more informed than the average tourist.

“Why are all the antlered ones together?”

“Do they ever fight?”

“Have you seen any mountain lions or wolves eat the elk?”

The sleigh driver, Max, takes it all in stride. It’s better than the usual: “At what age do deer become elk?”

“The ‘antlered ones’ are the boys. They are called bulls,” Max said. “This time of year, they aren’t much interested in the girl elk, called cows. They would rather hang out together.”

“Sounds like my husband,” one teacher mutters into her scarf.

Bull elk will also spar a little bit, especially the younger ones. It’s more horsing around. Nothing like the serious battles in August and September when bull elk are in rut, fighting over their harems.

As for predators, wolves can sometimes be spotted off in the distance. Mountain lions are more nocturnal and are rarely seen during the day.

Sleigh Bells Ring

The refuge’s most popular educational program takes place from the unique setting of a horse-drawn sleigh. Wheels are attached to the wagon when snow is not abundant enough; otherwise, the wagon glides on skis.

Sleigh rides began for the season Dec. 16. They operate daily through April 6, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., depending on conditions. Double H Bar hosts nearly 40,000 visitors for sleigh rides every season.

The one-hour ride is a perfect way to observe and photograph wildlife on the refuge. In addition to elk, passengers routinely see bison, moose, coyotes, bald eagles, trumpeter swans, ravens and other wildlife.

Max explained to the school group that sleighs are able to get very close to the elk because they are used to seeing them. As long as a person does not leave the sleigh, the elk are very tolerant of humans.

“If you were to get out and walk around, the elk would scatter,” Max assured. “They aren’t used to that.”

A refuge ride is similar to a safari outing, rather than a more zoo-like experience at Yellowstone Bear World or Bear Country USA. The elk, and all other animals within the 24,700-acre sanctuary, are truly wild. A careful balance is maintained to ensure all wildlife on the refuge remains wild.

True enough, the school kids’ sleigh pulled right up to a trio of bull elk all laying down in the snow. You could almost reach out and touch them. One bull with a massive rack munched contentedly while the other two gazed off into the distance, unbothered to say the least.

“When do they get fed,” asks one first grader.

“Usually in the morning. They’ve already eaten today,” Max said.

Elk on the refuge are most active in the morning when they are fed. They will lay down and conserve energy in the early afternoon. In the evening, they will begin grazing again. If they are being fed that day, they tend to group together to eat in the morning. Once the feed is gone, they will spread out more throughout the day.

Elk are fed alfalfa pellets and grass hay during the harshest winter months. Each elk will eat up to 8 pounds of feed per day. Refuge managers move the figure eight feeding pattern every few days to fresh ground to minimize impact to any one area. They also make every effort to keep feed spread out with contagious disease like chronic wasting disease and brucellosis a constant threat.

Feeding Starts

Elk typically arrive on the refuge in November or December, depending on weather conditions. Last year, snow started Nov. 1 and never quit. It was the type of long, cold, snowy winter that would have certainly taken more of a toll on the Jackson herd had they not received supplemental feeding.

Anywhere from 4,000 to 11,000 elk have used the National Elk Refuge just north of the town of Jackson. The average is around 7,000, and that figure is trending downward, which has feds pleased as the pressure to reduce or discontinue supplemental feeding has been growing.

Refuge managers would like to get the numbers down to about 5,000 head.

Lately, certain groups like the Greater Yellowstone Coalition have warned that supplemental feeding of elk is allowing unnaturally inflated herd numbers and could create a breeding ground for disease. Proponents of the refuge say a safe winter haven and occasional feeding is owed the species for usurping much of their winter habitat and annual migration route.

The refuge is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, an agency of the Department of the Interior. In addition to elk, the agency feeds bison and protects habitat for bighorn sheep, mule deer, trout and 147 bird species.

Eric Cole is the refuge biologist. He sees a late start to the feeding program this winter season.

“Currently, snowpack depth is less than an inch at our headquarters monitoring site, which is four times less than average for this time of year,” Cole said. “Forage production was above average last growing season, and we have had very few elk using the refuge so far this season.

“All signs are pointing to a later than average feeding start date, but that can be subject to change if snowfall increases.”

In December 2021, elk also got a late start on their seasonal migration to the feedgrounds. The bulk of the herd did not begin arriving until Dec. 19.

Early arriving elk forage what they can until snow is too deep or crusted for them to paw down to it. That’s when Cole and company begin feeding.

“For a historical perspective, the average feeding start date on the refuge is Jan. 24, but that date varies depending on conditions. There has also been 10 years where the refuge has not fed at all, with the most recent nonfeeding year being 2018,” Cole said.

In the spring, elk begin migrating off the refuge toward their summer ranges. The majority will follow the receding snow line up to higher elevations in surrounding Grand Teton National Park and Bridger Teton National Forest.

All About Antlers

“When will their antlers fall off,” asks a kindergartener.

“Beginning in late February through March, the bulls will start to drop their antlers,” Max said. “Though some of the younger bulls might keep theirs into April.”

Elk antlers are prized by collectors. Antlers also are used by crafters in making furniture, knife handles and a wide variety of other items.

Local Boy Scouts get first crack at collecting any and all sheds they can find about a week before the refuge opens to the public in the spring. The antlers are then auctioned off at a weekend-long community celebration called ElkFest.

Last year, 9,696 pounds of antlers were sold at the auction, roughly 2,348 pounds more than 2022. Bidders paid an average of $22.53 per pound of antler this year, down from last year’s average of $27.41 per pound.

In all, $218,382 was raised during the auction. Jackson District Scouts retain 25% of the sale’s proceeds. The remaining 75% are returned to the National Elk Refuge.

How The Refuge Came To Be

The valley’s first settlers recognized the value of big game like the elk. They knew early on that Easterners would relish the opportunity to see or hunt western Wyoming’s big game.

But it didn’t take long to fence up Jackson’s Hole. Ranchers needed enormous acreage just to raise a few hundred beef cows to get them through a winter. Whether the elk came out of the hills to winter easier in the valley or whether they were bottled up along a historic migration route mattered little — they came just the same.

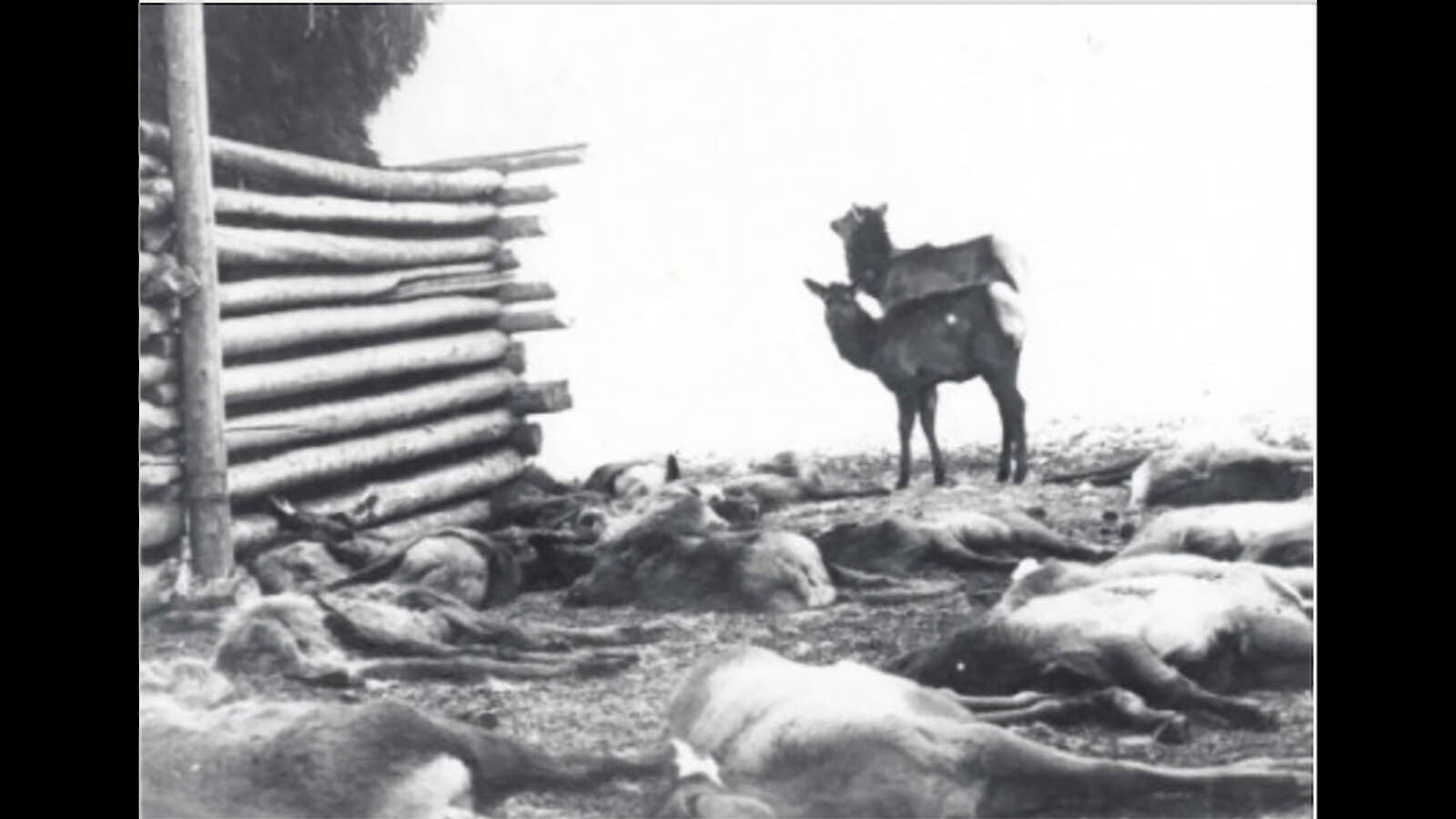

Ranchers fed them when they could and watched them die when they could not spare the hay.

A series of severe winters (1889-90, 1909-10, 1911-12) cut a herd of an estimated 50,000 to fewer than 10,000.

Stephen Leek is widely considered the godfather of the National Elk Refuge. His photographs of the 1909 carnage went a long way toward moving hearts and opening wallets.

By February 1911, the Wyoming Legislature passed a memorial requesting U.S. Congress cooperate with the state in preserving the elk. A month later, Congress appropriated $20,000 “to be made available immediately for feeding and protecting the elk in Jackson Hole.”

On Aug. 10, 1912, Congress appropriated $45,000 and decreed the creation of a National Elk Refuge, which consisted of 1,000 acres of public land and 1,760 acres of purchased land along Flat Creek to constitute the refuge. DC Nowlin became the first refuge manager.

Additional acreage would be added in later years until the refuge reached its current size of just under 25,000 acres.

JACKSON HOLE’S ELK — A TIMELINE

Timeline through newspapers shows what led up to Aug. 10, 1912, and the creation of the National Elk Refuge.

March 4, 1890 – Cheyenne Daily Leader

It is estimated that between 8,000 and 10,000 elk are wintering in Jackson's Hole, Uinta County. Besides these are large herds of deer, moose, mountain sheep and antelope. Ranchmen guard their haystacks to save the feed for their cattle.

May 2, 1891 – Cheyenne Daily Sun

“Elk in Danger,” proclaimed the headline. [Tom Cooper] says there are no less than 5,000 elk feeding over 100 miles [south of Yellowstone] and that the Indians will go in soon and kill hundreds just for sport. Some white men came down from Montana last fall and slaughtered many elk.

May 12, 1891 – Lander Clipper

The complaint of the slaughter of game by Indians is greatly exaggerated ... Indians are not always the greatest offenders in this slaughtering of game. Some years ago, a party of Englishmen came into this section to hunt and slaughtered over 400 head of elk near the Tetons and took away only four or five pairs of antlers, leaving all the carcasses to rot in the valley of the Snake River.

Sept. 16, 1893 – Cheyenne Daily Leader

Life in a comparatively unknown part of Wyoming is a hunter’s paradise. The section lies directly under Yellowstone Park and is being gradually settled ... even in this, the remotest corner of Wyoming, the onward march of civilization is noticeable.

Small herds of cattle are the rule, as all stock must be fed in winter. In time, the winter range will improve as the elk are killed off. These animals, driven down by deep snows in the mountains, winter in the valleys by the tens of thousands.

March 12, 1894 – Cheyenne Sun

Update from Jackson’s Hole to the Sun: Leeks Flat, Wyo. — Ranchmen are running short of hay on account of the short crop last season. There is no sickness here, but the ranchmen sit up just the same to keep the elk out of their fields. Elk are dying by the hundreds here on account of the heavy crust on the snow.

April 14, 1895 — Cheyenne Daily Leader

Update from Jackson’s Hole: The first settlers located in here about twelve years ago and now there are sixty-five improved ranches.

May 29, 1896 – Wheatland World

The decision of the United States Supreme Court is notice to all Indian agents as well as to the Indians themselves that Indians as well as white men are subject to the game laws of Wyoming, and that the elk, antelope and other wild game still remaining in the state should not be wantonly destroyed in the future.

May 1, 1897 – Evanston News Register

True, a loss to the settlers of the valley occurred through the starvation of the elk calves, yet as reported in the state papers ... [T]he loss is not 75 percent of the yearlings. From the careful and conservative estimate of men who know, I am of the opinion that the loss will not exceed 2,000 head all told.

March 24, 1898 – Rock Springs Miner

[Letter to the editor from Albert Nelson]: Our little settlement is slowly but surely coming to the front and if Uncle Sam don't annex these parts for a gaming preserve, Wyoming can justly be proud of counting Jackson’s Hole as part of this state. (A bill was introduced in 1898 to increase Yellowstone NP from 3,321 square miles to 6,566 square miles, fully encompassing Jackson Hole).

In regard to the game question, I honestly believe that the settlers of this locality take as much, if not more, pride and do more actual work for the protection of game than the balance of the state. It is surprising that, knowing the amount of revenue the state receives from hunting licenses and the amount of money eastern tourists annually leave in our state, our legislature does not do anything to help. Something has to be done and quickly too.

Feb. 28, 1899 – Laramie Boomerang

[Observation by a visiting journalist]: Immense stacks of hay were surrounded by two parallel fences about eight feet high and the same distance apart. It was explained that these were necessary in order to keep elk from destroying these stacks in winter. The necessity for this protection had been abundantly manifested the winter previous. It had been of unusual severity and thousands of these animals had been lost.

May 16, 1900 – Wyoming Tribune

A ranchman of Jackson Hole has presented a claim to the state for $50 for hay destroyed by an elk, the killing of which [is] prohibited by law. The state auditor rejected the claim.

April 26, 1901 – Crook County Monitor

Reports from the northern part of Uinta County say that during the past winter hundreds of head of elk have starved to death in the Jackson's Hole country. For time immemorial the animals have been in the habit of wintering in the hole, where the snow does not get as deep as in other parts of the country, making it possible for them to dig down to moss and other food.

Within the past three years the country has been settled up to such an extent that practically all of the old feeding grounds have been fenced in by ranchmen and, returning to the winter pasture as was usual, the animals were unable to break through the fences and get the pasturage and slowly died of starvation.

There seems to be no remedy for the trouble, and sportsmen can only look on with sorrow.

April 14, 1903 – Cheyenne Daily Leader

State Engineer Fred Bond has received a letter from C. W. Lee residing in the Jackson Hole country. In which Mr. Lee denies the reports sent out that thousands of elk have perished from starvation in northwestern Wyoming during the past winter. Mr. Lee says the winter has been quite severe and that while a number of elk died the reports sent out greatly exaggerated the loss. The snow is now rapidly melting and elk are in good condition.

May 11, 1904 - Cheyenne Daily Leader

“WILL CULTIVATE ALFALFA FOR ELK.” The announcement that the government intends this spring to sow a large acreage in Yellowstone Park to alfalfa for the feeding of elk and other animals during the winter is being received with much satisfaction by the ranchmen in the northwestern part of the state.

There are thousands of elk and deer in the park and in the Jackson's Hole country, which have been in the habit during past winters of coming down out of the mountains in the winter and causing great annoyance and loss to ranchmen by breaking into their pastures and open haystacks.

March 31, 1905 – Crook County Monitor

“Elk Frozen in Snow,” read the headline. A dispatch from the Jackson Hole country states that during the severe cold spell of February many elk perished, and that owing to the unusual snowfall in that section the animals would necessarily remain in the valleys of the settlements until April.

In vicinities where feed has been short, hundreds of elk have visited ranches and attempted to get at hay and alfalfa in stacks. Previous experience, however, had taught ranchmen that such visits might be expected and in a majority of instances haystacks are enclosed in corrals and safe from depredations of the big game.

March 7, 1907 – Wyoming Tribune

Headline: “ELK STARVING.” Band of 150 in Jackson Hole Country now eating quaking aspen bark. Game Warden organizing dog teams, similar to those in Alaska, to make an attempt to carry feed into the animals by this method.

Feb. 20, 1908 – Cheyenne Daily Leader

“For First Time in History Successful Moving Pictures Are Taken of Big Game at Close Range.” Were you at the Elks Home last night to see S. N. Leek's moving pictures of Wyoming game?

State Game Warden D. C. Nowlin states that there are now about 25,000 elk in the Jackson Hole country that are worth $2,500,000 to the state, and that they have not decreased in number during the last four years.

He opposes any form of a national game reserve, but believes that the state of Wyoming should set aside a state reserve and take drastic measures to protect this magnificent band of animals from the fate that befell the buffalo.

Feb. 15, 1909 – Laramie Boomerang

“Thousands Will Die,” the headline read. [W. J. Kelley interviewed]: Last Saturday afternoon I counted and estimated at least 7,000 elk in the Jackson Hole country, and the condition of those creatures is pitiful indeed. These elk will stay up in the hills as long as they can get anything to eat, and then the cows and many of the others will come down into the valley to graze.

And when they do come down they are hungry, and everything they strike goes as completely as though it was ravaged by the grass-hoppers. Fences will not keep them out and ranchmen have to sleep at their stacks and guard them or they would have no hay in a few days after the herd strikes the country.

I want to tell you that this is a serious matter, and it makes a man's blood boil to think that in the face of it all the legislature is apparently dead to the situation ... It is a case which ought to be handled by the humane society, and if something is not done, we who live up there are going to see what the reason is. We are tired of being ignored ... [t]he state has got to feed these animals or pay the ranchmen for doing so.

Jan. 2, 1910 – Cheyenne State Leader

“Don’t Desire Game Preserve. Citizens of Jackson Hole Country Protest Against Action Which Legislature Requested.” The last legislature memorialized congress to set aside $30,000 for the purchase of eight townships in Jackson Hole, Wyoming for use as a game preserve or refuge for the 35,000 wild elk which range in that section.

The citizens of Jackson Hole have now joined in a protest to Congress against such action, pointing out that the proposed reserve is little frequented by elk, that it supplies insufficient feed and that it would be utterly impossible to herd the 35,000 wild animals onto the preserve and keep them there.

March 14, 1911 – Laramie Daily Boomerang

During the opening day of the sixty-first congress, Senator Warren secured an amendment to the agricultural bill appropriating $20,000 for feeding the starving elk of Jackson's Hole, Wyoming, and for the removal of a portion of them to better feeding grounds in other parts of the state.

July 20, 1912 – Laramie Republican

Senator Warren has succeeded in obtaining legislation of to protect and preserve the wild elk of the Jackson Hole region, $20,000 for feed and $45,000 for the “establishment of a winter game (elk) preserve or refuge ... which shall be located in that section of Wyoming, south of the Yellowstone park, and shall include not less than two thousand acres ... and the secretary of agriculture is hereby authorized to purchase said lands with improvements, to erect necessary buildings, and to incur other expenses necessary for maintenance of the reserve.”

Jake Nichols can be reached at: Jake@CowboyStateDaily.com

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.