Wyoming is home to three historic sites where thousands of settlers on their way West in the mid-1800s stopped to scratch their names in rock walls.

It was the social media of the time and remains significant today because those travelers saw fit to leave their marks on Wyoming for posterity.

Register Cliff in Platte County, Independence Rock in Natrona County and Names Hill in Lincoln County are all places where emigrants left their marks on Wyoming, and all three places are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Crossing Wyoming on a dusty trail in a horse-drawn covered wagon wasn’t for the timid. Powerful rivers and mountain ranges separated by miles of dry, sagebrush-covered desert were challenges that claimed many lives.

Wagon trains covered an average of eight to 20 miles per day. That meant at the end of a long day they could often look back over a vast sea of Wyoming desert to the place where they camped the night before.

Names Hill

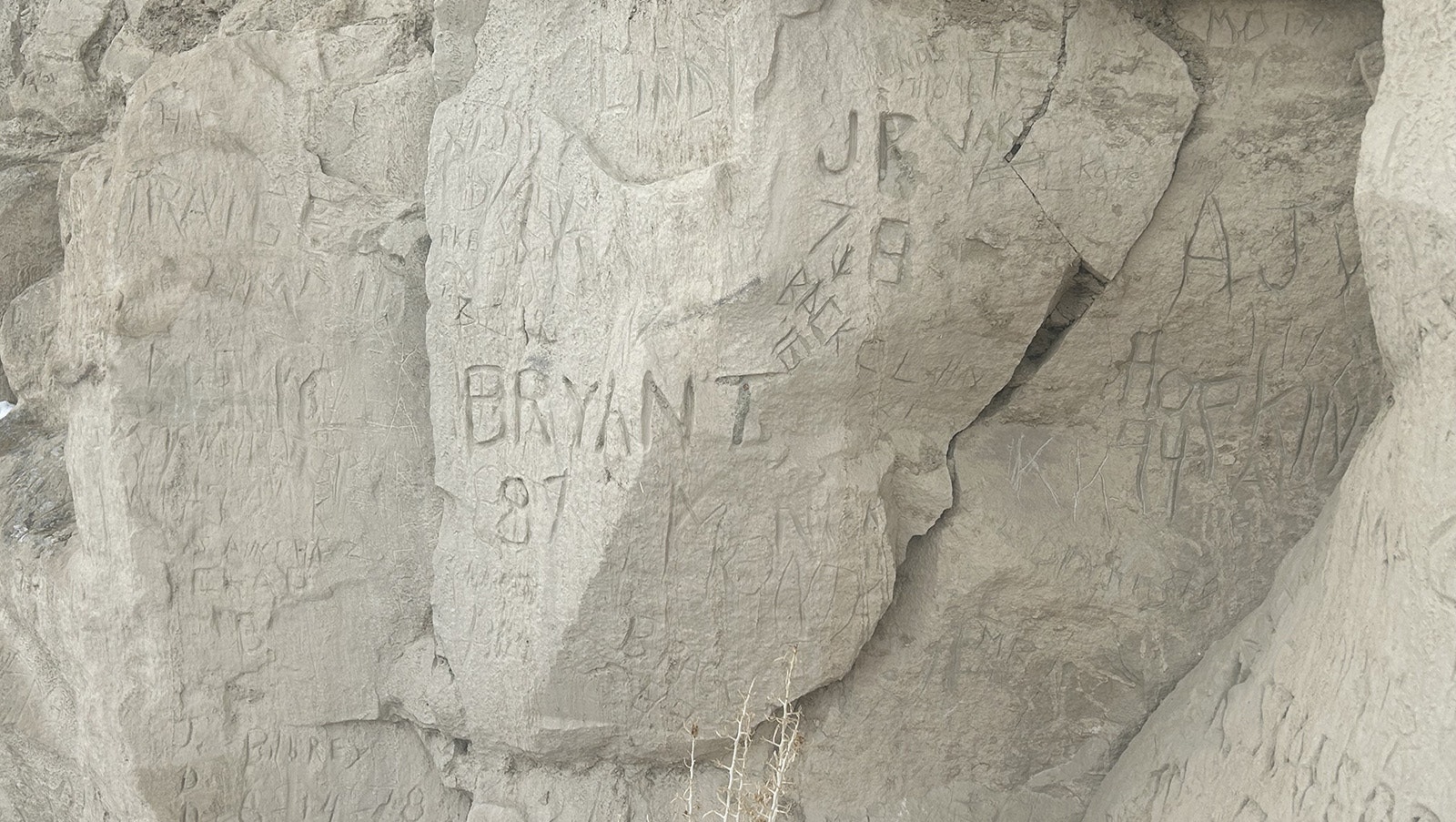

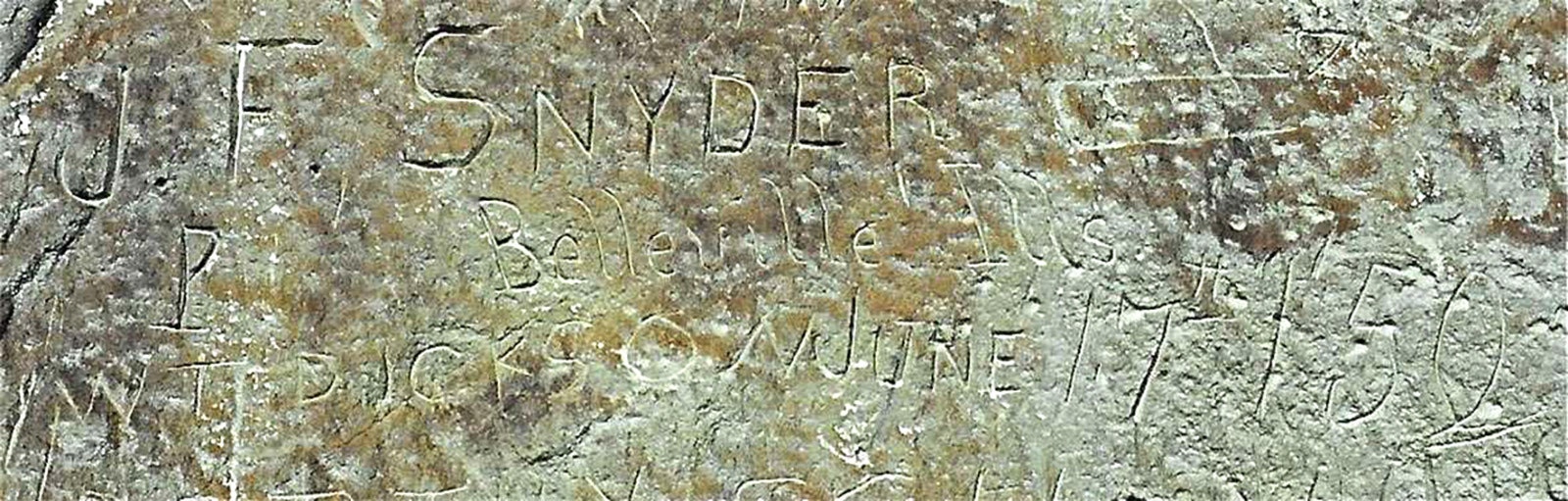

Dudley Gardner, an archaeologist and historian with Wyoming State Parks, said it’s uncertain how many names are scratched into the rock at Names Hill in Lincoln County.

“By the time they got to Names Hill they had been in Wyoming for a long time,” he said. “They wanted others to know who passed through. It’s a registry of those who traveled the West.”

Gardner said many of the names are hard to see at different times of the day because of the angle of sun hitting the rock wall. The stone is also eroding due to the freeze thaw cycle and exposure to sunlight and water.

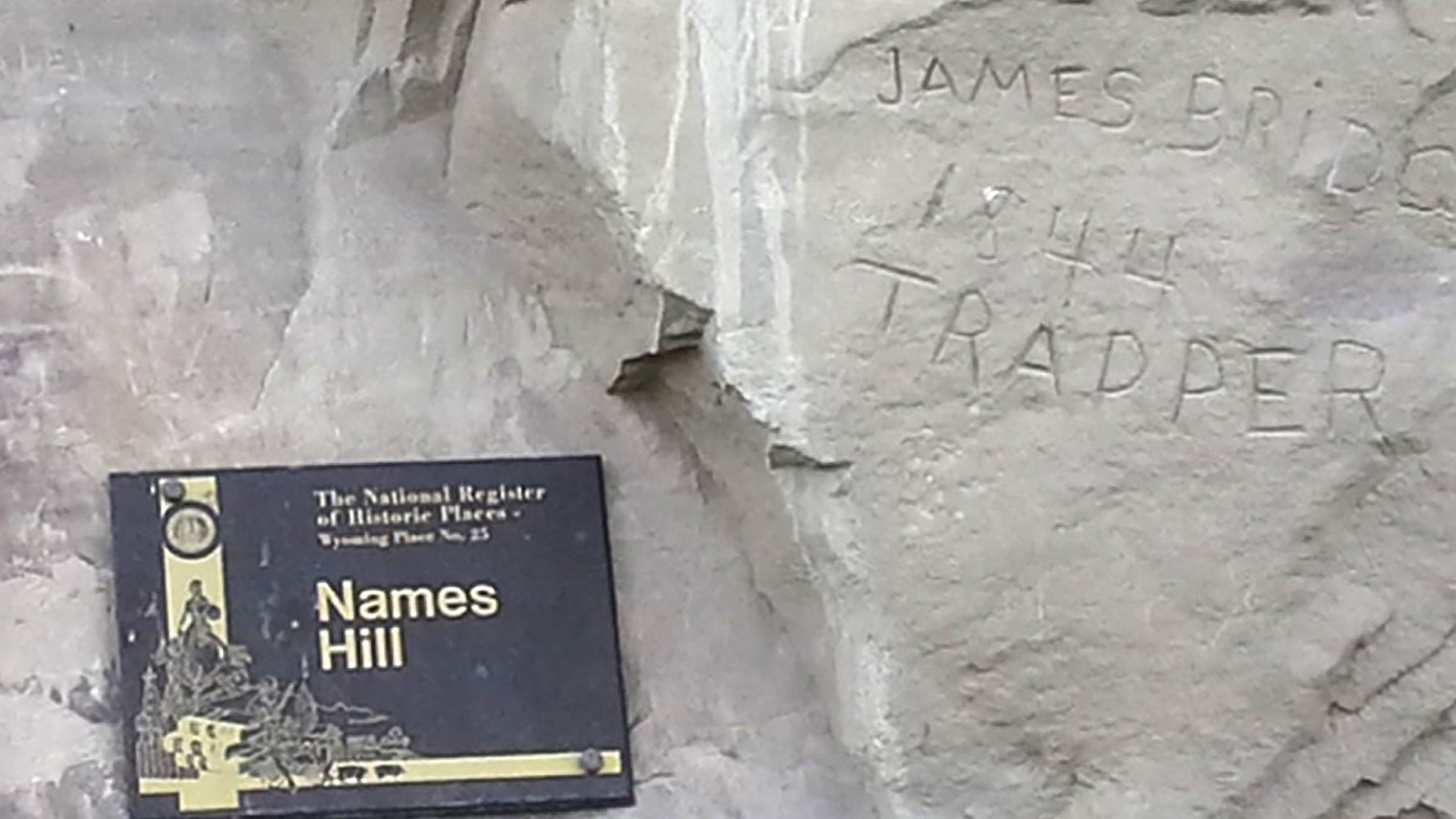

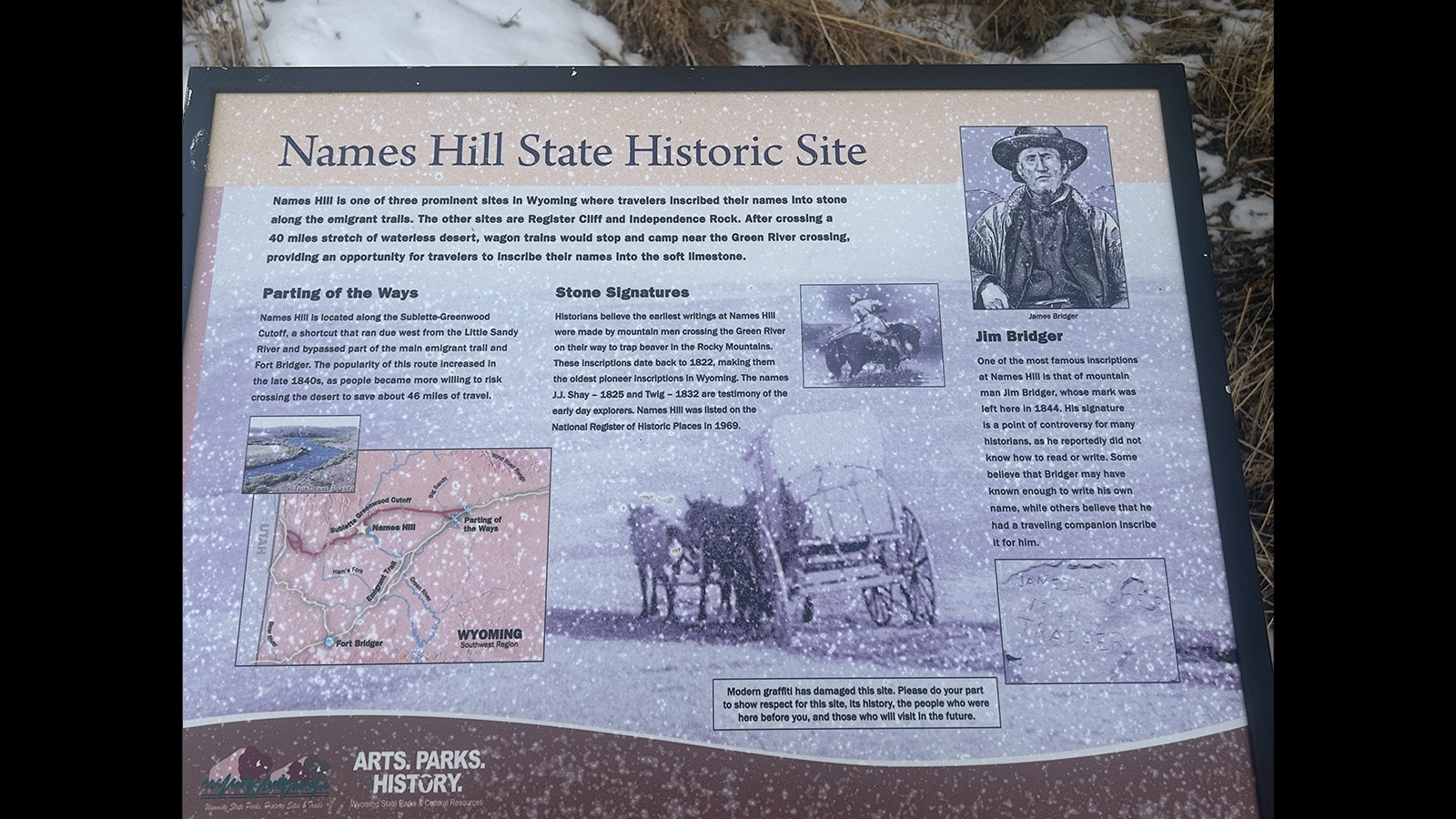

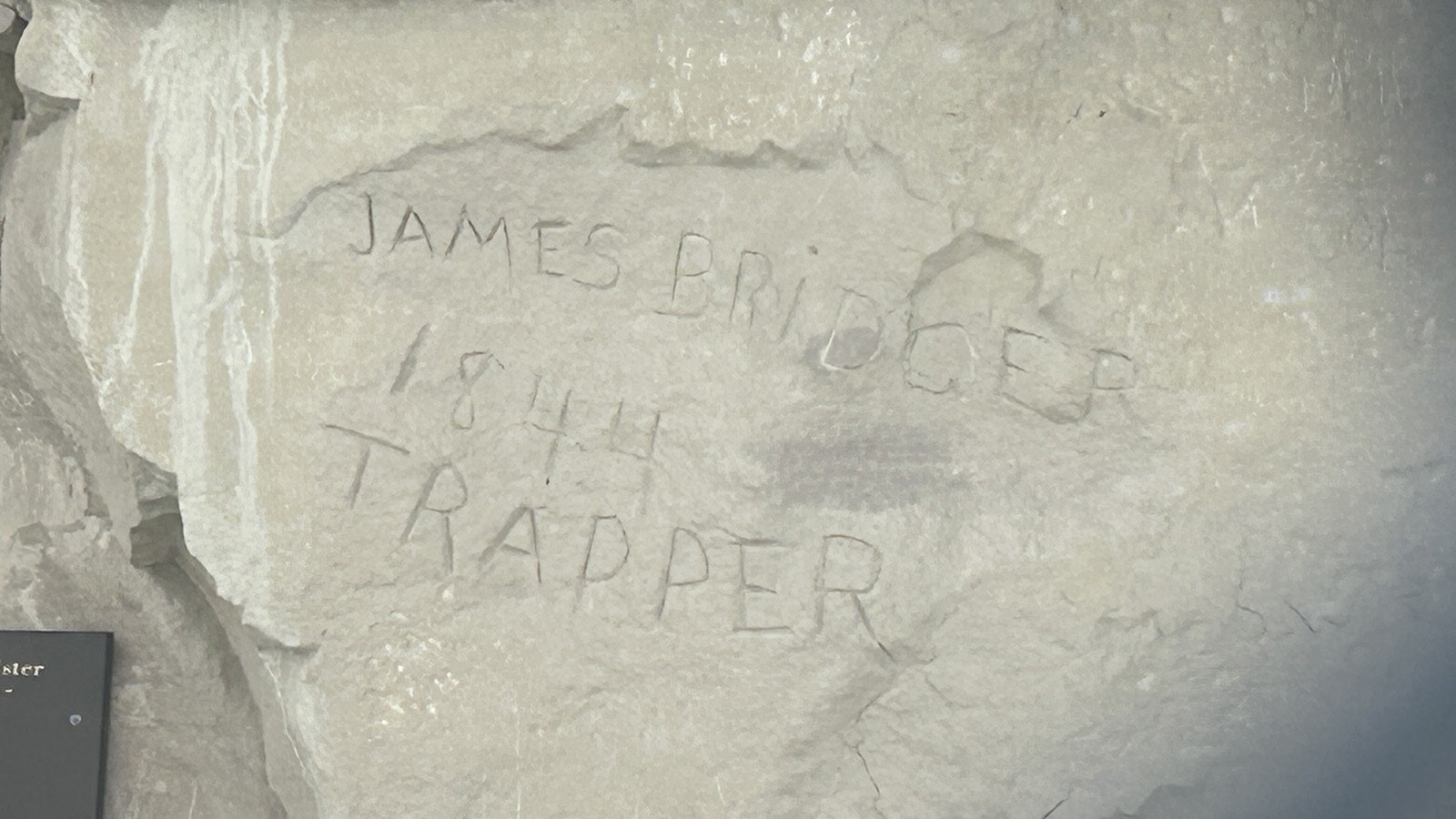

“James Bridger Trapper 1844” is one of the most famous inscriptions at Names Hill. The carved name is controversial among historians because Bridger reportedly could not read or write. Gardner said Bridger’s signature of record, found on other confirmed documents, is an X.

Two mountain men who carved their names into Names Hill are J.J. Shay in 1825, and Twig in 1832. These are believed to be the oldest pioneer inscriptions in Wyoming.

River Ferries

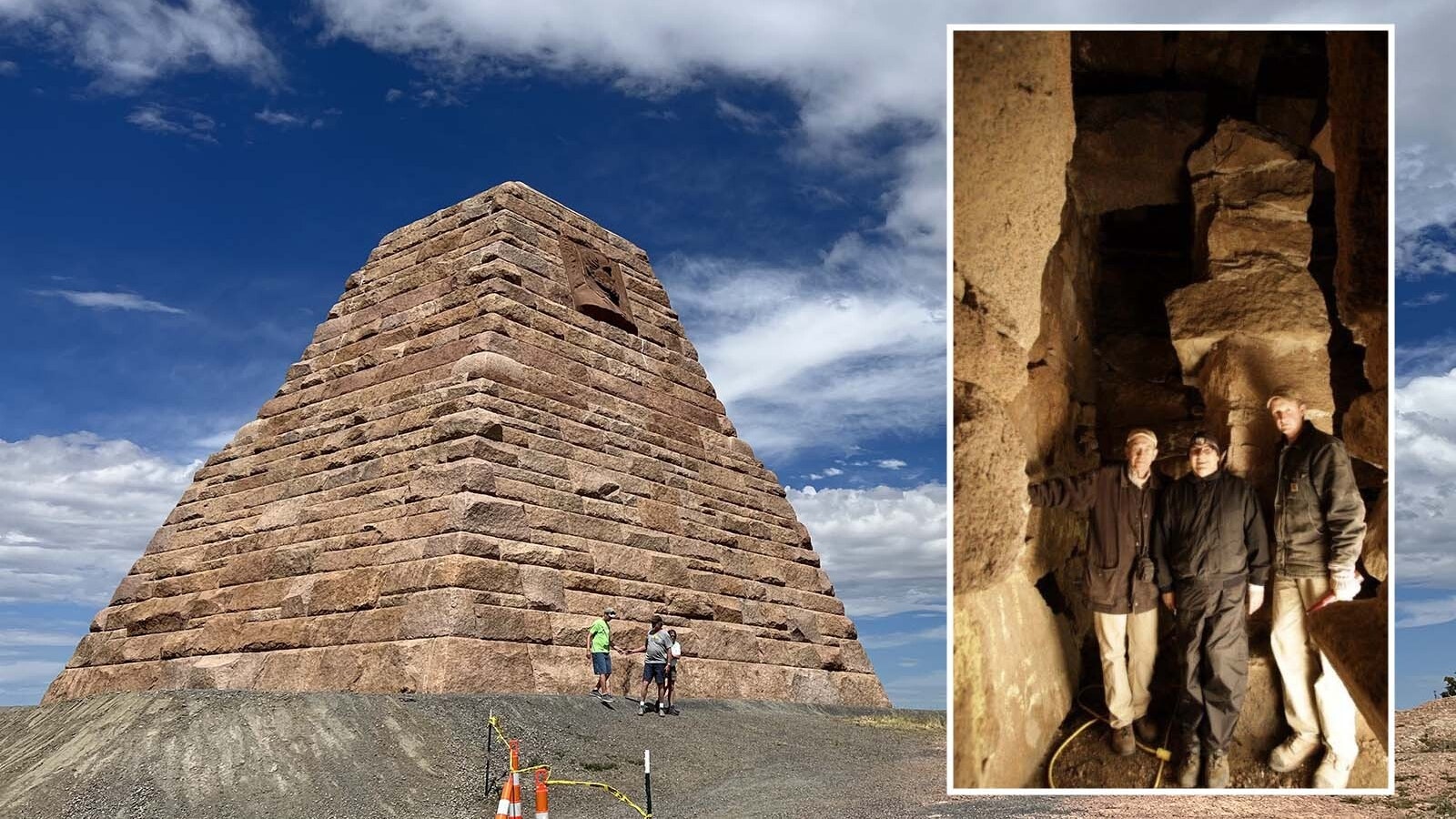

Among the reasons emigrants congregated at Names Hill was a ferry crossing. There were numerous ferries on the Green River and they moved up and down the river with changing river conditions.

Jim (James) Bridger was a partner in a ferry operation near Names Hill and records show he ran a trading post in 1841 at a crossing on the Green River south of the present-day city by the same name.

Bridger’s business acumen makes Gardner question the assumption that Bridger was illiterate.

Bridger was part of several businesses but most of his money was tied up in livestock. Gardner said the river bottom area near Names Hill had grass and water and that made it a prime area for rehabilitating tired livestock.

After crossing 40 miles of dry desert between South Pass and Names Hill, called the Sublette Cutoff, the livestock and wagon travelers generally needed a break.

“A long rest on good pasturage generally restored the oxen, horses or mules to health, and then they were once again marketable,” according to the Utah Historical Society in a publication titled “Mormons, Mountaineers and Utah’s Forgotten County.”

Records show Bridger traded fresh horses and other livestock with emigrants on the trail at a rate of two tired animals for one fresh animal. That allowed his herds to grow considerably and made for a lucrative business.

Ferrying customers across the Green River was also a profitable business. It cost between $3 and $6 per vehicle for a ferry ride across the Green River and there were five ferries that operated on the river during times of high water.

Gardner said the ferry crossings on the Green River and the North Platte River were places where a lot of emigrants died. Drownings were frequent, as was hypothermia.

“Some people say only five% of Americans could swim in the 18th Century,” Gardner said. “They didn’t have swimming lessons like we do today and I wonder if it even crossed their minds that it would be an issue while crossing a desert.”

By 1860, more than 250,000 people had crossed Wyoming on the California, Oregon and Mormon trails combined, according to the Utah Historical Society.

Independence Rock

Independence Rock in Natrona County is located about 60 miles southwest of Casper. It received its name because wagon trains leaving Missouri in the spring hoped to arrive there by Independence Day – July 4.

The explorer John C. Fremont camped near Independence Rock in August of 1843. Fremont recorded the following in his journal:

“Everywhere within six or eight feet of the ground, where the surface is sufficiently smooth, and in some places sixty or eighty feet above, the rock is inscribed with the names of travelers. Many a name famous in the history of this country and some well-known to science are to be found among those of traders and travelers.”

Fremont carved a large cross into the rock but it was blasted off in 1847 by Protestant emigrants traveling the California/Oregon Trail. According to the book “Memoir of the Life And Public Services of John Charles Fremont,” by John Bigelow, the protestants considered the cross a symbol of Catholicism.

Register Cliff

Located in Platte County, Register Cliff was a key navigational landmark for wagon train travelers because it allowed them to verify that they were on the correct path toward South Pass and not moving into impassable mountain terrain located farther north.

The cliff is located near the North Platte River and the earliest signatures on the rocks there date back to the late 1820s.

According to the National Park Service, an estimated 500,000 emigrants used the Oregon, California and Mormon trails between 1843 and 1869 with up to one-tenth of them dying along the way. Many of their names are recorded for posterity on rock walls in Wyoming.

John Thompson can be reached at John@CowboyStateDaily.com