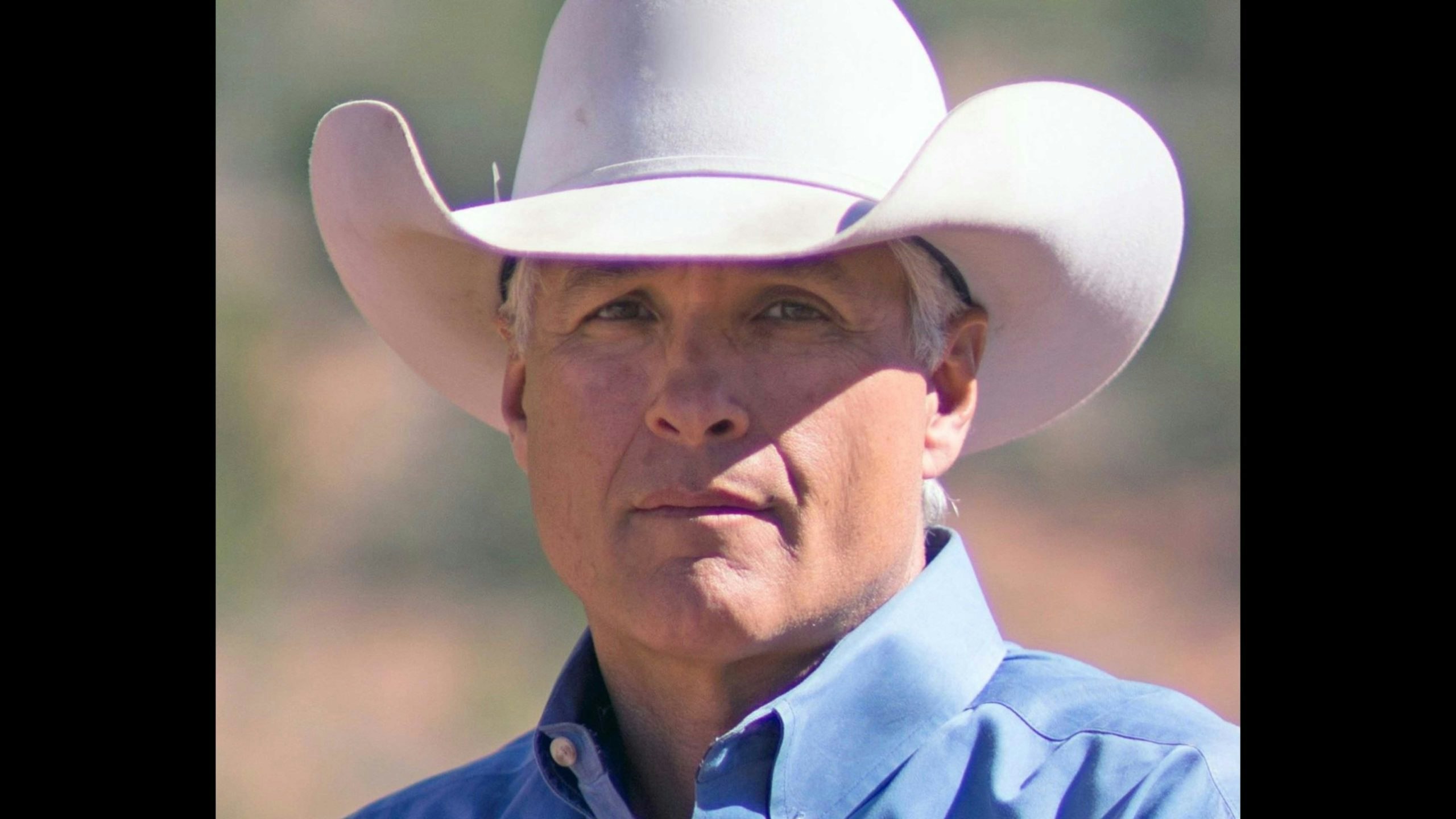

CASPER — Sculptor Chris Navarro believes following one’s intuition can lead to good places. It’s worked for him.

The renowned Casper sculptor recently shared with Cowboy State Daily how his artistic career was forged. There were no sculpting classes, just muscular, angry livestock and drilling rigs.

“I started out bull riding,” he said.

As a teen, Navarro saw his first rodeo in Madrid, Spain, where his family lived because of his father’s role as an officer in the U.S. Air Force. Those cowboys on broncos and bulls were inspiring.

After graduation, he followed a path that led him to Casper College to try to become good enough for the professional rodeo arena. That led to a degree in animal science and experience on the rodeo circuit.

Life’s Hard Knocks

Then life’s, and especially rodeo’s, hard knocks came calling.

“All you can look forward to is being broke and getting hurt,” he said about the prospects of a rodeo career.

With his pro rodeo dream gone, Navarro started working as a pipe inspector for oil rigs. Inspiration was hard to come by, even though he inspected the pipe on Wyoming’s deepest well at 20,000 feet.

“It was not my dream job, for sure,” he said. “I wanted to do more with my life.”

In 1979, the then 23-year-old and a friend were hunting and decided to visit his friend ’s cousin, who served as caretaker for famous Wyoming sculptor Harry Jackson’s home and studio in Lost Cabin.

“I had no idea my life was about to change,” he said.

There in front of him was the bronze “Two Champs" that depicted the famous rodeo bronc Steamboat in the process of sending the cowboy to the dirt.

Navarro thought he wanted to buy it. Then he asked the price and heard “$35,000.”

The Beginning

While that kind of money was beyond his oil field paycheck, something inside said he could make his own bronze.

“The very next day I visited Goedicke’s Art Supply store in Casper. I had never been in their store, either. I told the owner John Goedicke that I wanted to make a bronze sculpture and asked if he would sell me the supplies I needed to get started,” Navarro said. “I put all the materials in my truck and drove to the Natrona County Library.”

There he asked the librarian to help him locate all the books on sculpting. He took them home to his trailer, knowing his first work was going to be about bull riding. He started to create using the trial-and-error method, spending nights and weekends at his task.

The hours were not enough. He decided to use one of his annual two weeks of vacation to get it done. His oil field buddies thought he was crazy.

“Somehow, I knew that it would change my life,” Navarro said.

Once the bull riding sculpture he called “Spinning and Winning” was completed he took it to a Cody bronze-casting foundry owned by Bucky Hall. (Navarro still uses the foundry today.) The cost in 1980 was $1,000.

“I used my savings and went and had it cast,” he said. “Bucky Hall said it was a nice sculpture for my first one.”

Hall entered the sculpture into a contest and Navarro won, a prize of $15.

“I said, ‘I am on to something here,’” Navarro recalled. “I just kind of fell in love with making sculptures. I had no idea you could make a living creating sculptures.”

The Leap

Navarro went back to the oil field and kept working nights and weekends on his art. In 1986 and married to his wife, Lynne, and soon after with their 10-month-old son J.C. in tow and another baby on the way, Navarro turned his back to the rigs and pipe and picked up clay full-time.

“I was a self-employed artist with a 10-month-old and another on the way,” he said. “I picked the two worst professions if you wanted to make a stable paycheck— rodeo cowboy and artist.”

But success builds on success.

His first bronze was 19 inches high. In 1990, he did his first more life-size commission piece. Later, he did several pieces for a Colorado collector. Opportunities kept coming for him to showcase his skills doing large sculptures.

“I started doing one big monument every year,” Navarro said. “Once I started doing it full-time, I never had to go back and do another job. I was able to support my family with my sculpture.”

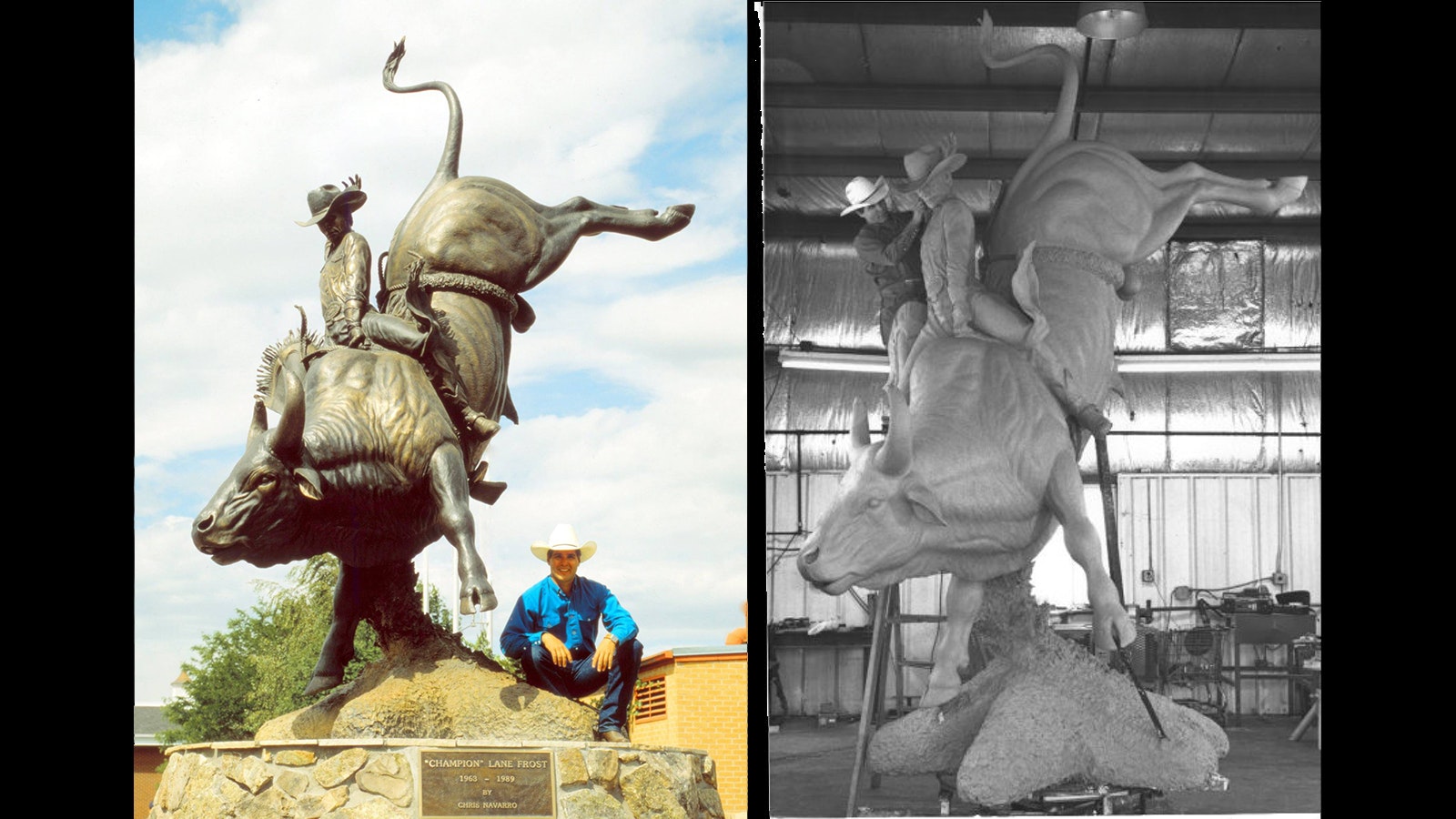

He still recalls his work on a sculpture honoring world champion cowboy and bull rider Lane Frost, who was gored to death by a bull at Cheyenne Frontier Days in 1989.

“One night after I drove past Cheyenne Frontier Park, Frost’s image would not leave me. I knew I had to create a monument that would capture his image and his spirit,” Navarro said.

The Project

Navarro had tried to raise money for the sculpture from the Frontier Days Committee and was denied. He decided to raise the $150,000 himself, offering everyone who donated $1,000 a miniature bronze of the piece. The money came in.

Because the 15-foot piece would be impossible to make in his studio at the time, he went to Caleco Foundry in Cody. As he was nearing completion March 6, 1993, he lay on the bed in the foundry, living there to get the project done.

He had been using an electric heater to help keep the clay warm enough to mold it. That clay had a petroleum base. He woke up at 3 a.m. to smoke and fire.

“I had to call 911 and jump out of a second-story window,” Navarro said. “It ruined the sculpture and I had to redo it.”

He ordered new tools and clay and finished it days before the planned dedication in Cheyenne on July 26, 1993. The piece was his first large public monument and lives at the Cheyenne Frontier Days Old West Museum.

Dozens of sculptures later, including 16 around Casper, the artist continues to follow his intuition.

New Visions

This winter Navarro is working in his studio where he owns a gallery in Sedona, Arizona, on a piece he’s calling “Canyon Cat.” It involves some abstract design, a cat and the Grand Canyon.

“I’m going to be 68 next month and I am trying to do sculptures that I haven’t seen,” he said. “Sometimes I get these ideas in my head.”

Navarro has no plan to retire and the desire that fired him up at Lost Cabin remains tangible in his talk.

The hands of the former pipe inspector have generated six one-man art shows and put pieces in 13 museums. Those same fingers molded 36 monumental and life-sized bronze statues in varied places across the West and nation.

“I don’t know how many more big monuments I have in me,” Navarro said. “But if someone wants one, please contact me.”

For all those in dead-end jobs who want to follow a dream, Navarro advises it will take a lot of work to make that dream a reality and most likely require some self-promotion.

And listen to those thoughts spurred by the cowboy on Steamboat, he said, adding that, “I’ve always tried to listen to my intuitions.”

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at Dale@CowboyStateDaily.com

Dale Killingbeck can be reached at dale@cowboystatedaily.com.