This story doesn’t make the rounds much anymore. There was a time in the late 1990s when you couldn’t get away from it.

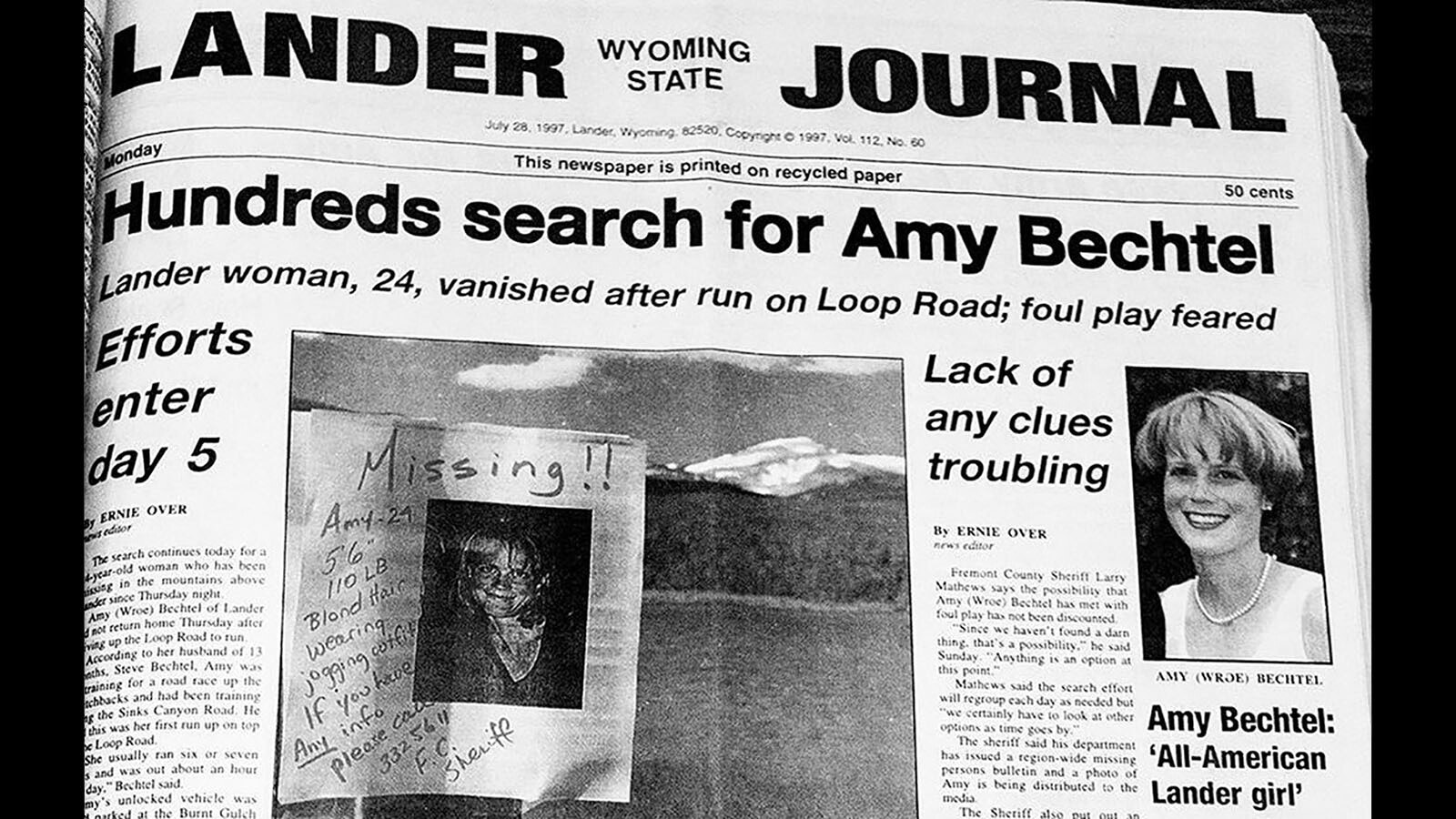

The unsolved disappearance of Amy Wroe Bechtel in 1997 remains one of the more baffling cases in U.S. history. The massive search launched when she vanished was like no other in Wyoming then or since. It was a hunt so exhaustive even the Russians were asked to assist.

The young, fit athlete went jogging in the Shoshone National Forest, and not a trace of her was ever found.

Posters, flyers and signs went up everywhere — for years. There were two dedicated websites and an 800-number hotline monitored 24/7. A grieving husband spearheaded efforts to find his missing newlywed bride even after he was considered the prime suspect.

Meanwhile, as the years would unravel, a better suspect was believed to be camping nearby in the area Amy went missing. He was a man so heinous he was the only inmate on Wyoming’s death row up until a year ago. A monster who fits every profile of a serial killer.

Was Amy one of his victims? Did the husband do it? Or is she still alive today and unable or unwilling to show herself?

Steve And Amy: The Early Years

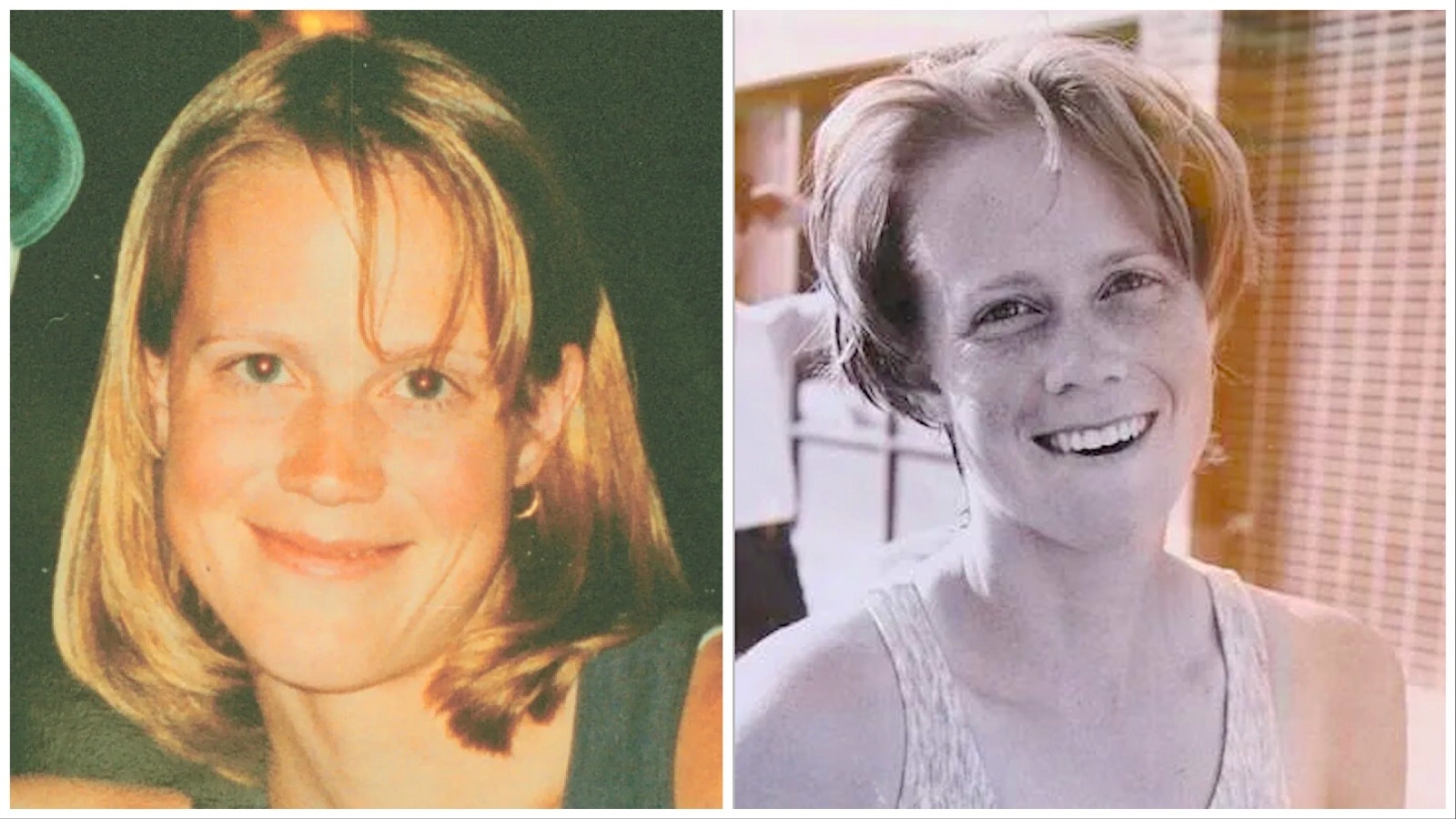

The Bechtels, Amy and Steve, met in college at the University of Wyoming. They both studied exercise physiology. The couple began dating in 1992, moved to Lander together after graduation in 1994, and were married in June 1996. Amy was 24, Steve, 27.

Amy was born in California but grew up in Wyoming, mostly in Jackson, where the family moved to shortly after her birth, and in Douglas, where they later moved to.

Amy was the youngest of four siblings, two sisters and a brother. Amy’s father Duane passed away in 2000. Mother Jo Anne taught school for many years in the Powell area until her retirement.

Steve was born in Casper, the son of Thomas Bechtel, an architect now deceased, and Linda Bechtel, who was the director of a school for developmentally disabled children. Steve has a younger brother, Jeff, and an older sister, Leslie.

Among many things, Amy was primarily a runner. Not particularly gifted in high school but a late bloomer, perhaps. She captained the UW cross-country and track teams and still holds the UW record in the 3,000 meters. After college, she hoped to qualify for the 2000 Olympics as a long-distance runner.

Since high school, Steve has been infatuated with rock climbing. Relatively obscure in the 1990s, climbing has quickly become a mainstream outdoor activity. Steve now owns and operates Elemental Performance + Fitness Gym in Lander and runs a climbing training program, Climb Strong.

On July 24, 1997, the day Amy disappeared, the couple was living in a cozy cottage at 9 Lucky Lane, one of 10 on the secluded hipster block that came to be known locally as “Climbers’ Row.”

They were renting the place from their neighbor, free-climbing pioneer Todd Skinner and his wife Amy Whisler. The Skinners were also part-owners of Wild Iris Mountain Sports where Amy and Steve both worked part-time.

Ordinary Start To An Unremarkable Day

It was a Thursday and a scorcher on that fateful day in July. Both Amy and Steve had the day off from work at Wild Iris Mountain Sports.

Amy thought about taking the day to drive to Powell and pick up some furniture from her parents’ place but canceled at the last minute. She had too much to do in Lander on her only day off, she told her mother.

Amy and Steve had breakfast at home and then went their separate ways at around 9:30 a.m.

Amy had a list of errands to run before heading out to the Loop Road to map out a 10K run she was planning. She envisioned a rugged hill climb with runners finishing at Frye Lake where they could jump in to cool off.

Steve took the couple’s dog Jonz and met up with a travel writer buddy from Jackson, Sam Lightner. They rendezvoused in Dubois, an 80-mile drive for Sam, 70 miles for Steve. The pair were checking on potential climbing routes up Cartridge Creek.

Amy taught a 90-minute youth weightlifting class at the Wind River Fitness Center where the owner, Dudley Irvine, described her “in a good mood.” Nothing out of the ordinary.

She then made a few phone calls — phone company, gas company, insurance company — in preparation to move into the $90,000 home they had bought at 965 McDougall Drive just days before.

A little after 2 p.m., Amy paid a visit to Camera Connection on Main Street in Lander. Owner John Strom made no unusual observation of Amy other than to note she wore a jogging outfit: yellow shirt, black shorts, running shoes.

Strom then sent Amy upstairs to Gallery 331, a portrait studio, to see Greg Wagner about framing a few photos she was entering in a contest. Wagner remembers Amy glancing at her watch during a brief encounter. Again, nothing unusual or memorable.

She left around 2:30 p.m., the last confirmed sighting of Amy.

Gone Girl

Steve returned home to Lucky Lane around 4:30 p.m., he guessed, a little earlier than he expected. The new climbing route north of Dubois never panned out and it began to rain, so he and Lightner packed up. Phone records confirm Steve made a call from the couple’s cottage at 4:43 p.m.

Steve would later tell investigators he was not immediately worried about Amy. The couple was not in the habit of leaving notes for each other. Neither owned a cellphone.

At around 8:15 p.m. Steve had dinner with the Skinners, who also lived in the Lucky Lane complex. By then, he was definitely becoming concerned. The Skinners invited Steve to an 8:45 showing of “Con Air,” but Steve said he was too worried about Amy for a movie and wanted to be at home.

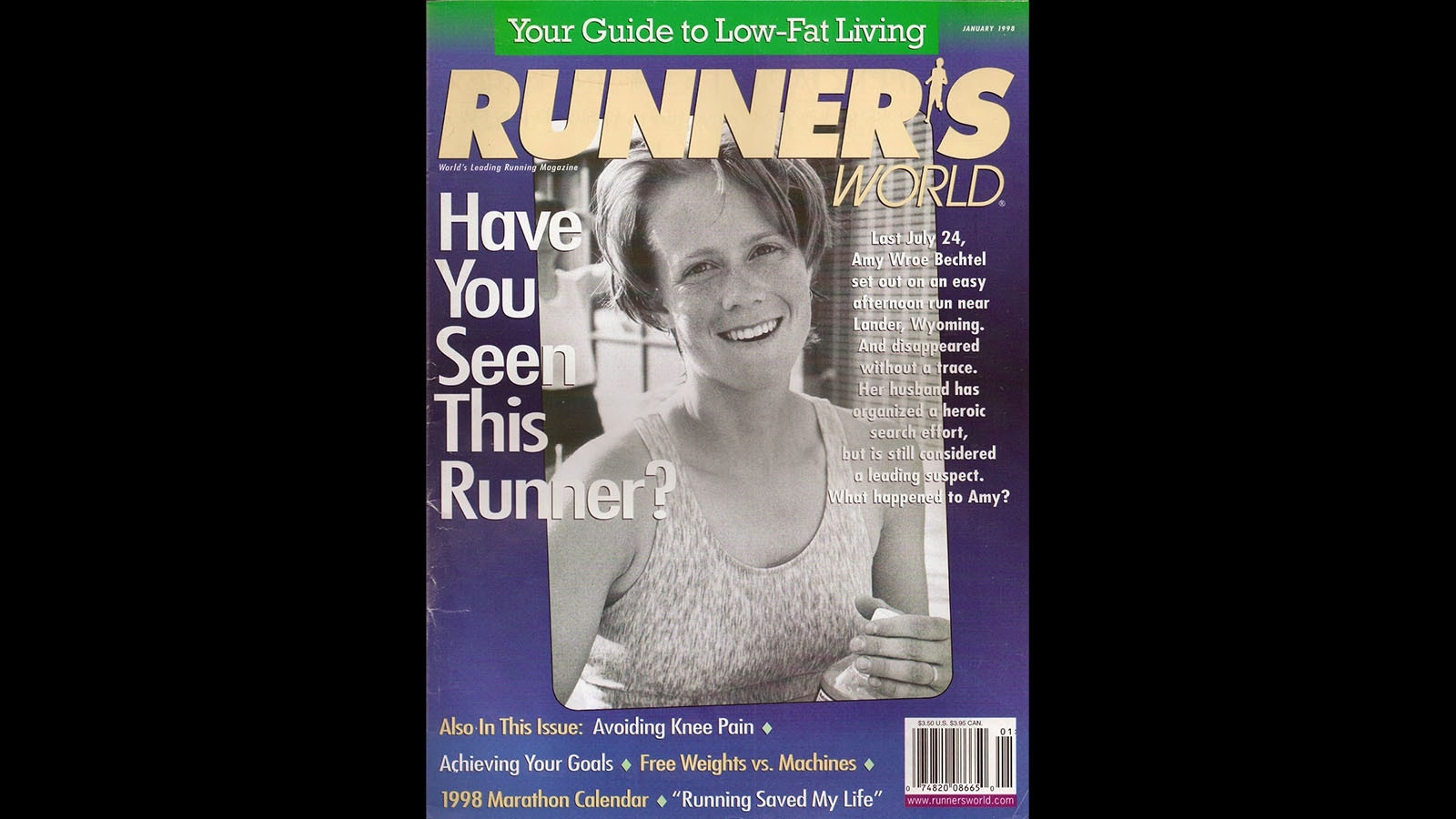

Years later, Bechtel would grant a rare interview with Runner’s World when he recalled that night.

“It was funny,” Steve told writer Jon Billman in 2016. “I got home from climbing, it’s just a normal day — get unpacked, feed the dog or whatever, then I start wondering, ‘Where is she?’ Make some calls, drive around a little bit. It gets to be like 8 p.m., 9 p.m., 10 p.m., that incredible anxiety builds up. You’re just worried. I hope she didn’t break her ankle. I hope she didn’t run out of gas. Those normal things where you’re like, ‘this sucks.’ But you’re not going, ‘I hope my wife wasn’t grabbed by some psychopathic serial killer.’”

Steve called Amy’s parents in Powell around 10 p.m. to see if maybe she did end up driving there on a whim. He also tried the local hospital. Nothing.

At around 10:45 p.m., Steve made a call to the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office and reported her missing. Two deputies were dispatched to the home and preparations were made to get search and rescue on it first thing in the morning.

When the Skinners returned from the movie around 11 p.m., they volunteered to drive around places Amy may have gone running off Loop Road, a 30-mile back road through Shoshone National Forest connecting Sinks Canyon Road with Louis Lake Road.

Sometime around 1 a.m. after an hour of driving, the Skinners found Amy’s white Toyota Tercel station wagon parked at a turnoff for Burnt Gulch. The car was unlocked. Not unusual for Amy or many Wyoming residents at the time. The keys were found on the passenger seat under Amy’s “to-do” list with four of its 13 items checked off, right next to her expensive sunglasses.

The only thing unusual was Amy’s green Eagle Creek wallet. It was not in the car and never found. She never took it running.

Todd called Steve from his cellphone telling him he found his wife’s car. Steve grabbed a friend, Kirk, some lanterns and a sleeping bag and took off for Burnt Gulch.

Chasing Amy

They searched all night. Several friends also arrived before dawn to help. They were joined by the official search party early on the morning of July 25. By the weekend, more than 200 searchers — most of them well-trained professionals — scoured the area.

The search mission began with an intensive scouring of the 5-mile radius around Amy’s vehicle. A day later, that expanded to a 20-mile radius, then a 30-mile radius on day three with 300 people assisting in the effort.

“We know what we’re doing,” lead investigator Dave King of the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office told media outlets at the time. “We have 50 activations a year. We have specialists in steep-angle searches, swift-water searches, cave rescues. We have trackers, air spotters and cadaver dogs, which supposedly can catch scents even underwater.”

For the first five days, the search included multi-jurisdiction search and rescue teams with trained tracking dogs, along with others on horseback, on ATVs and dirt bikes, or on foot. The National guard was called in. Civil Air Patrol provided fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, one outfitted with infrared heat-seeking technology.

If Amy was lost or hurt she would have been found. Period. If she was attacked by a bear or mountain lion, the dogs would have alerted. Searchers would have found something of her remains or clothing.

After five fruitless days, investigators began to suspect foul play. After eight days, the search was called off.

Case Turns Criminal

The missing persons case turned criminal investigation after that first week. The only thing anyone seemed to agree on was Amy was not the type of person to vanish voluntarily. That ruled out a runaway or suicide.

More than two dozen Federal Bureau of Investigation and Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation agents arrived from Denver and surrounding areas. They set up shop in the sheriff’s office and stuck pins in a map. They questioned everyone, chased every lead.

The FBI even obtained NASA satellite images of the area. They came to nothing. Months later, the FBI turned to Russia after learning their Mir space station had also taken satellite photos of Wyoming at that time. Extensive cloud cover prevented those from being of use.

Specially trained scent dogs followed one trail, then frustratingly backtracked. A footprint believed to be Amy’s was eventually lost in the efforts, trampled by searchers. Other potential evidence was also compromised in early blunders when volunteer searchers believed they were simply looking for a lost hiker.

Sgt. John Zerga, who decades later took over the cold case, admitted mistakes were made.

“We didn’t close off any routes out of here. We didn’t close off any vehicles. All we had was a bunch of people up here looking for a missing runner. We actually ruined it with the vehicle, because we allowed the Skinners to drive it home. [The investigation] was not good for at least the first three days. There was a lot of stuff that was lost,” Zerga was quoted as saying in a Runner’s World article.

Lead investigator King may have been in over his head as well. He had just been promoted to detective from county jailer. He joined the search days late because he was away on a horse packing trip at the time of Amy’s disappearance.

King handed the case off to Detective Sgt. Roger Rizor after two months and focused on his campaign for sheriff. King would later resign that position Nov. 3, 2000, and was subsequently convicted of drug use and stealing cocaine from the department’s evidence room.

Husband Becomes Prime Suspect

Both King and Rizer zeroed in on one suspect from the beginning: the husband.

"If a man's wife disappears mysteriously, you don't clam up, you don't refuse to cooperate with the cops," Rizor told the Billings Gazette.

Steve’s alibi appeared lock tight. Lightner vouched for him, said they were together in Dubois most of the day. Lightner recalled stopping at a store in Dubois and buying a hammer. Records show the purchase though the shop owner did not recall either man.

In fact, no third-party verification placing the two in Dubois has ever been made. It would seem unlikely that Lightner would lie for his friend, though. In later interviews, Lightner admitted to a falling out with Steve, adding he actually got along better with Amy.

Detectives also could not verify the phone call to the hospital that night, and had other minor timeline discrepancies.

All the while, however, Steve was leading search groups, helping put up posters of his missing wife and willfully participating in investigators’ interviews — four such sessions to Steve’s count.

The investigation hit a wall Aug. 5, when an FBI agent named Rick McCullough attempted to strongarm Steve (a common interrogation tactic), accusing him of murdering Amy. He said he had evidence linking him to the crime. Steve figured he was bluffing, but it freaked him out enough to lawyer up.

Steve hired Wyoming lawyer Kent Spence, son of famed attorney Gerry. The Spence Law Firm advises all of its clients to refuse a polygraph because they are “unreliable, inadmissible in court, and prone to false positives.”

Steve was quoted as saying, “The polygraph is like one of those monkey traps. Anybody who needs me to take that test — I don’t need them in my life.”

When Steve would not submit to a lie detector test it was a red flag for Amy’s brother, Nels, who has to this day pressed him to take one.

A search warrant was obtained in early August. The Bechtels’ place was thoroughly searched along with Steve’s pickup. Cadaver dogs smelled nothing. Luminol tests, which pick up the tiniest fraction of blood even if it has been painted over, came back negative.

Investigators found no incriminating evidence whatsoever, but the search did turn up suspicious old journals in which Steve had written some dark poetry concerning power, death and killing. Steve claimed they were written as song lyrics when he was in a punk band in high school long before he ever met Amy.

Steve quickly became a polarizing force. Townies and Amy’s family were suspicious of him. He came off as cocky. Hiring a high-profile lawyer like Spence didn’t win him any points, either. His refusal to grant further interviews with investigators is still a red flag for some.

On the flipside, the NOLS crowd and other fitness hipsters in Steve’s circle were quick to come to his defense. No way could he have done something to hurt Amy, they said.

Marital problems? No one other than Nels saw that as a reality.

Skinner, who was a close friend, a landlord and a boss, said, “They were the sweetest couple I ever ran across.”

Serial Killer On The Loose?

Steve said all along the cycloptic focus on him as the sole suspect hampered what could have been a more effective investigation. Zerga, who picked up the cold case in 2010, didn’t disagree.

The dogged pursuit of Steve by King and Rizor likely blinded them to other crucial evidence pointing toward the worst serial killer in Wyoming history.

In 1997, Dale Wayne Eaton was not yet fully on law enforcement’s radar. His first brush with authorities would not happen until just months after Amy’s disappearance when he was convicted of attempting to kidnap a family that had broken down on an isolated highway in the Red Desert.

Eaton’s brother Richard reached out to Fremont County detectives during this time and suggested Dale may have been involved with the Bechtel case. He told authorities he and his brother would often hunt and fish in the Burnt Gulch area where Amy’s car was found, and he thought Dale was camping there in the summer of 1997.

In retrospect, Zerga said the information should have been followed up on. “Few people camp there or even know of that area,” he said.

But the tip was basically ignored. Authorities believed Richard Eaton was more motivated by the $100,000 reward than actual justice. Plus, they were convinced they had their man with Steve.

“I think our detectives who were working the case were so adamant that it was Steve that they weren’t looking in other directions,” Zerga told the Casper Star-Tribune in 2013.

After spending a mere 99 days in jail for the attempted kidnapping, Eaton was eventually arrested again near Dubois on July 30, 1998, after violating parole. While being held, Eaton killed his cellmate in a fit of rage. Facing manslaughter charges for that, authorities learned something even more gruesome about the convict.

DNA samples taken from Eaton would link him with the 1988 cold case rape and murder of Lisa Marie Kimmell. An ensuing search of his property in Moneta turned up Kimmell’s buried car, as well as women’s clothing and purses, and numerous newspaper reports about other murdered and missing women.

Steve asked the Natrona County Sheriff’s Office if he might see some of those items in case there was anything he might recognize as belonging to Amy, but was reportedly denied.

Some authorities say Eaton may indeed be the Great Basin Serial Killer, a madman believed responsible for the murders of at least nine women in Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and Nevada between 1983 and 1997.

The Bechtel case also has many consistencies with those involved in the Kathleen Pehringer disappearance, a 41-year-old who went missing from nearby Riverton in 1989.

On March 3, 2004, Eaton was found guilty of raping and killing Kimmell. He was sentenced to death at the time. Endless appeals eventually bought Eaton a resentencing last year when he received life imprisonment without the possibility of parole.

Eaton has never cooperated with authorities regarding other cases of missing women. Zerga and an FBI agent tried to visit Eaton in Colorado in 2010, but the killer refused to see them.

Zerga followed up with Richard Eaton in 2012. The brother reiterated his conviction that Dale Wayne Eaton was camping in the area Amy vanished from around that time.

So, Zerga went back to the death row inmate in 2013. It was a short meeting, Zerga said. Eaton cursed him and told him “where he could go.”

When just a word, even from a hardened killer, could have set a family free, Eaton gave nothing.

Detective Zerga seems more and more convinced these days that it was Eaton who had something to do with Amy’s disappearance. Rummaging through cold cases, working with FBI agents involved in the Kimmell killing and speaking with Eaton’s family members have all led Zerga down the same path.

“There’s a good reason to believe Dale was involved with this,” he told reporters in 2013.

No Lead Too Crazy

In the early weeks, months and years of the investigation numerous false leads poured in from crackpots, to physic readings that never panned out, to mistaken eyewitnesses.

Nothing ever came of a report of gunfire on the night of July 24 at Louis Lake, 8 miles from Burnt Gulch, and a voice yelling, “Come on, you sissy, do it, do it!”

Abandoned mines, caves and crumbling homestead cabins were checked on the advice of psychics who saw Amy being held there. Divers checked the waters of the Popo Agie as it disappears in Sinks Canyon.

On Aug. 2, an unidentified woman called to say she saw a light blue pickup (Steve’s) speeding through a campground on Loop Road with a blonde woman inside around 5 p.m. July 24.

Months later, possible sightings of Amy in Salt Lake, Florida, New Mexico and Colorado all came to nothing.

A suspicious smell near Louis Lake reported by woodcutters turned up a dead deer. Investigators dug up the ground at another smell alerted to by cadaver dogs and found nothing.

A bottle discovered floating in the Middle Popo Agie River with a message inside reading: “Help. I’m being held captive in Sinks Canyon. Amy,” was dismissed. The handwriting did not match up.

The more reliable clues and tips came from a few eyewitness accounts that seem to confirm Amy did at least drive her car to where it was found and probably got out and began jogging.

Investigators discovered, at the bottom of the to-do list found in Amy’s car, a milepost description of landmarks that she had jotted down, while referring to her odometer, along the first section of the proposed route of the 10K race. That would indicate Amy was driving her car and not abducted at that point.

Investigator Rizor and the FBI followed up on stalker angles, checking out men in Amy’s past that were “obsessed” with her. One man in particular who moved to Lander to be closer to her. Another man who doted on her where she sometimes waited tables at a local restaurant.

Six years later in 2003, hikers found a watch up the middle fork of the Popo Agie matching the description of the one Amy was wearing when she went jogging the day she vanished. Bones found nearby were proved to be from an animal, and police could not determine whether the watch was really Amy’s.

Some tips were more useful than others. Investigators did manage to find at least three eyewitnesses who remember seeing someone fitting Amy’s description running on Loop Road that day she went lost.

A mechanic for the county remembers seeing a female jogger on the switchbacks of Loop Road that day. So, too, does a surveyor on a job that day.

Jim and Wendy Gibson, owners of the Pronghorn Lodge in Lander, also later recalled passing by a slender blonde woman in dark shorts jogging, swiftly, high up in the hills on Loop Road.

National spreads in The New York Times, People Magazine and Runners World failed to produce anything of value. Amy’s photo and information appeared on the jumbotron at University of Wyoming Cowboys football games. More than 270,000 missing posters were sent to the obvious locations in 40 states offering a $100,000 reward.

A 24-hour hotline was established and manned by Steve with his friends and family. A www.whereisamy.com website was created linking out to hundreds of other sites.

Still, the years rolled by with no useful leads coming in. Amy’s story was featured on “Unsolved Mysteries,” “The Geraldo Rivera Show” and “Disappeared.” New batches of tips were elicited at each airing but never any solid leads.

State newspaper Casper Star-Tribune ran a regular link in large bold lettering (HELP FIND AMY) on the homepage of its website through the remainder of 1997. A year later, it was still there, but in a smaller font and no longer bold. By May 1999 it was gone.

The case went cold.

Fewer Than 1%

It’s been 9,635 days since Amy didn’t come home, more than 26 years. She would be 51 years old today.

At this point, Amy is a rare statistic. Fewer than 1% of people reported missing are never found.

On average, 500,000 to 700,000 people are reported missing every year in the U.S. About 77% of those are found within 24 hours and 87% within two days. Only 3% of adults will be missing for longer than a week.

In this day and age with webcams, cellphones and other technology, it is difficult for someone to just vanish. But that is exactly what Amy Wroe Bechtel did in 1997.

For her family and friends, the worst thing is not knowing. It’s one thing to take a life. Killers like Dale Wayne Eaton do that. It’s another thing to take a death.

A silenced eulogy, a stolen memorial service. Not even a gravesite to remember her by. Amy Wroe Bechtel, like the rest of the missing, is not altogether alive nor convincingly dead. She’s a ghost.

For Steve, Amy is an ex-wife now. Steve had her declared legally dead in 2004. He has since remarried and remains in Lander.

He and his wife Ellen run their gym in Lander. They have two kids.

Steve has moved on from the past. The last interview he granted on the subject was in 2016. At that time, he had not met with his lawyers in a decade and had not spoken to Amy’s family in 15 years.

Steve also bears the weight of the condemned in the minds of some. At the very least, he has “prime suspect” still attached to his name on a Wikipedia page.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.