Kroger hasn’t missed a beat in preparing for its proposed $25 billion merger with Albertsons, which it says is “on track” to close in early 2024, despite a number of lawsuits and public opposition that have sought to slow or outright stop the deal.

In its third-quarter earnings call, company officials detail how they have continued to prepare for the merger, including dropping its debt ratio so that it will be well positioned to bounce back to target levels of debt post-merger.

Total debt to adjusted EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) is sitting at a ratio of 1.4 as of the end of Q3, as compared to a target ratio of 2.3 to 2.5.

Kroger CEO Rodney McMullen told investors the company has also filed paperwork with the Federal Trade Commission that certifies it has met substantially all of the FTC’s antitrust law requirements.

The filing, which was made in mid-November, starts a ticking clock for the FTC, which has until Dec. 15 to make a decision on the Albert-Krogerson deal.

FTC’s Options

The FTC has four possible responses. It could close the investigation and let the deal proceed, or it could impose additional requirements before the merger is approved. It could block the merger by filing a lawsuit in federal district court, or it could file an extension to delay a final decision and continue negotiations.

Nothing has so far been announced by the FTC one way or the other on the deal, but FTC head Lina Khan has taken a harder line on mergers and antitrust law than many of her predecessors. At a public forum in Colorado, however, she was careful to stress that she cannot stop a deal that can’t be shown to be anticompetitive.

“We continue to work cooperatively with the FTC and its review of the transaction,” McMullen said. “This step keeps us on track to close our proposed merger with Albertsons in early 2024. We are confident we have fulfilled all the commitments we set out in the original merger agreement.”

That includes a divestiture plan with C&S Wholesale Grocers, which has agreed to buy at least 413 stores from the combined Albert-Krogerson stores for $1.9 billion once the merger closes.

Under the terms of that deal, C&S could buy as many as 237 additional stores, depending on what the FTC requires to ensure robust competition in the marketplace. In that event, C&S would pay Kroger additional cash for each store, using an agreed-upon formula.

“C&S is a well-qualified buyer who meets all the criteria necessary to complete our transaction and will ensure no stores will close as a result of the merger,” McMullen said. “Frontline associates will remain employed, and existing collective bargaining agreements will continue.”

Continued Consolidation

The merger of Kroger and Albertsons continues a consolidation in the grocery store sector that opponents of the merger suggest is creating food deserts and lowering consumer choice in markets across the United States.

That dwindling choice was highlighted recently from the perspective of a grocery store worker in Cheyenne, Wyoming during testimony to Khan at a public forum in Colorado.

Tyler Welsh, of Cheyenne, told Khan he’s seen the grocery store sector become less and less competitive over the past 15 years as a result of mergers and consolidations, to the detriment of workers and consumers.

Each time there was one of these mergers, consumers and workers were told similar things, he added. Prices would go down, worker wages would rise.

“This simply did not occur,” he said.

Instead, what he witnessed was more of a “money grab” by private equity firms that left consumers with less choice, and sometimes caused longtime grocery store workers to lose pension plans and other benefits that had been part of their negotiated contracts pre-merger.

Further consolidation in the sector just isn’t the answer, he told Khan.

“Consumers want options,” he said. “During the 1980s, my community of Cheyenne at the time had a population of approximately 50,000 folks. We had many grocery options. Including Walmart, we had 11 grocery stores operated by seven different corporate entities.

Today, however, Welsh said there are just six stores left, operated by three different corporate entities, serving a population that now exceeds 65,000.

That loss of independent grocers has played out across Wyoming, Welsh said, leaving customers with fewer choices.

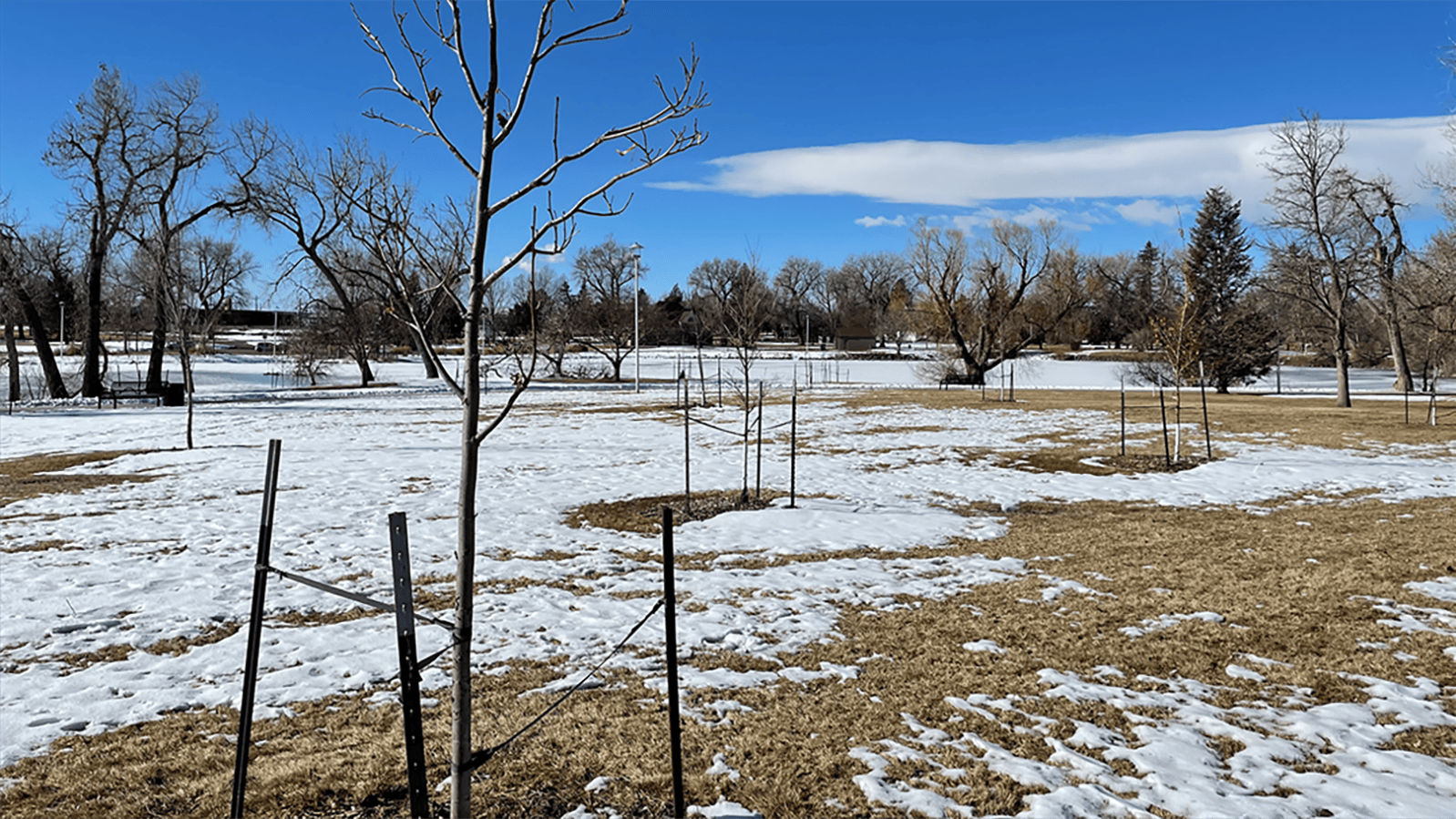

Meanwhile, data from the USDA’s map of food deserts shows that those grew in Wyoming following the 2015 Safeway-Albertsons merger.

Albert-Krogerson Merger Will Help Us Compete

Albertsons and Kroger have both said the company needs the merger to be competitive, pointing out how the sector is now competing with superstores like Walmart, Costco and Amazon, whose very size allows them to dictate retail prices that are, in some cases, lower than wholesale.

Kroger and Albertsons want some of that action to remain competitive.

“Our proposed merger with Albertsons creates meaningful and measurable benefits for our customers by lowering prices, beginning on Day One,” McMullen said. “(It) extends our commitment to associates by increasing wages and benefits and deepens trust with our communities by keeping stores open to assure America has access to fresh and affordable food.”

McMullen said the companies have already been working together through “integration teams” to ensure there is continuity for customers and associates once the merger deal closes.

“It’s exciting to see the complementary strengths of both organizations, and how we’ll be able to learn from each other to provide customers with an even stronger food retail experience and compete even more effectively against larger non-union operators in the future,” he said.

Strong Profits Despite Disinflation, Increased Wages

Kroger, while saying it needs the merger to remain competitive, has continued to report strong profits throughout a trying time in the sector, as has Albertsons. Those gains have continued despite more recent disinflationary trends, even as Kroger has already taken some steps to substantially increase wages.

For example, the average retail price of fuel was $3.77 in the third quarter, versus $3.84 last year, Kroger officials reported during the earnings call. Yet, Kroger’s cent-per-gallon margin on fuel was higher this year at 57 cents for the quarter, as opposed to last year’s 50 cents.

Through its loyalty program, customers are saving 14% more in rewards through fuel purchases compared to last year, Kroger Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Gary Millerchip said.

This shift to customer loyalty programs has helped shield the company from customers who are just shopping in the store for sale items that won’t make the store any profit, company officials said during the earnings call.

Those additional profit margins were realized in spite of raising worker wages 33 percent in the quarter, and finding a collective $1 billion in cost savings by year-end, through “eliminating waste in areas that don’t affect customer experience.”

There were no specifics on what’s being cut, whether it’s labor positions or something else, but it’s now the sixth straight year the company has reported a billion dollars in cost-savings.

Those six years of successful cost-trimming include a significant chunk of time where consumers paid record prices for the food on their tables.

Digital sales at Kroger have meanwhile grown by double digits during the quarter, Kroger reported, rising 11%, although the overall volume of items sold continues to lag and hasn’t improved at expected rates.

“As a team we are laser-focused on returning to unit growth and expect improvement in volumes to continue for the balance of the year,” Millerchip said.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.