There’s a post-World War II building boom happening across Wyoming and you step into an outhouse overhanging the Wind River and settle in to do some business. Suddenly, a loud voice shouts out from the chasm underneath you, prompting an acceleration of that business, and you run out in terror and embarrassment.

From a nearby bar, a man laughs as he puts down a microphone.

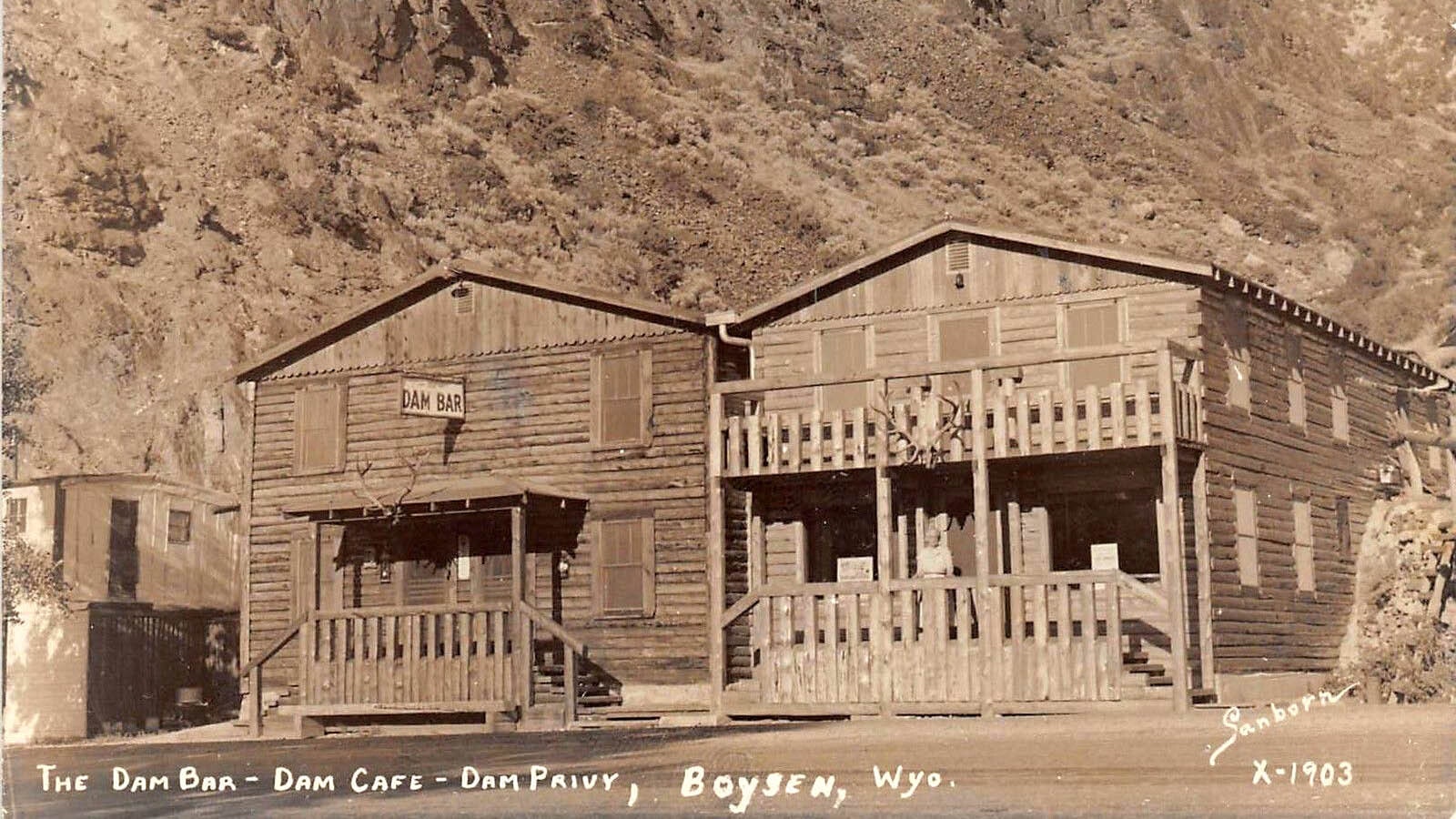

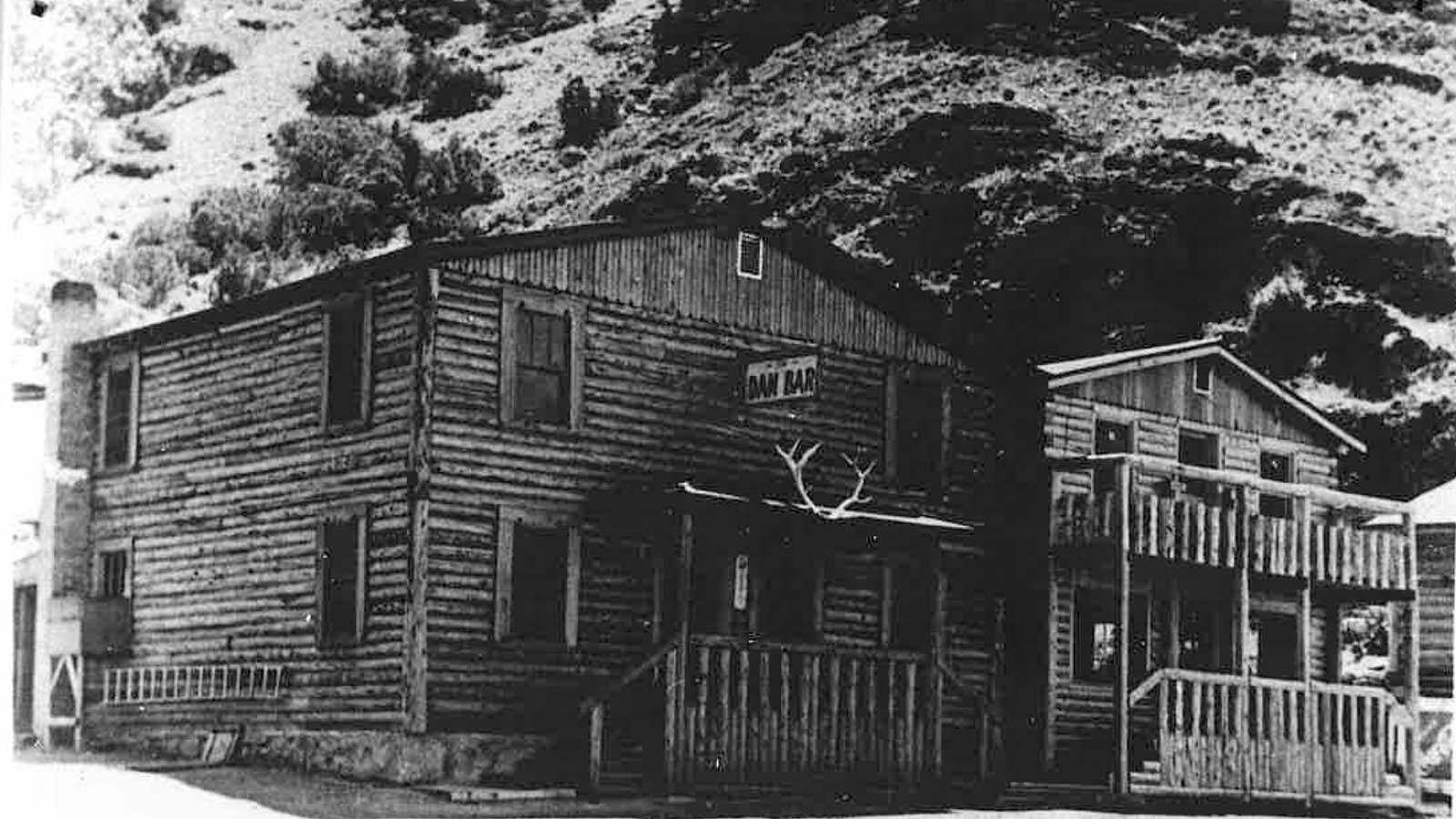

Many Fremont and Hot Springs County residents didn’t have to imagine. They witnessed it firsthand at the Dam Bar and Privy, a notorious watering hole at the southern end of the Wind River Canyon near the Boysen Dam.

There are many crazy but true stories associated with The Dam Bar and Privy, a relic of the Old West that had a brief, but colorful, history in the 1940s and 1950s.

“It was a very busy period, a very colorful time,” said Jackie Dorothy, tourism director for Hot Springs Travel & Tourism. “Some people still remember their parents going to it. They said kids were sent to the café while the parents went to the bar.”

‘The Best Damn Bar By A Dam Site’

The Dam Bar and Privy was the enterprise of Barney Smith, one of Hot Springs County’s most colorful characters. Smith was a member of the Farlow Family, which included Albert "Stub" Farlow, the man depicted riding Steamboat in Wyoming’s trademark bucking horse and rider.

The Farlows have a long history of Old West debauchery going back to the 1870s when the family settled in Lander. At least one Farlow was a known associate of Butch Cassidy’s gang of outlaws.

Barney Smith reveled in the family history while building his own reputation in the region. He was already running a bar and pool hall in Thermopolis when he embarked on a more ambitious venture at the southern end of the Wind River Canyon.

“He had quite the business going on,” said Dean King with the Hot Springs County Museum. “And I think he did really well. He was quite the promoter for his time.”

Several structures, most likely built by the Farlow family, were already standing at the southern end of the Wind River Canyon near the tunnels on U.S. Highway 20 between Thermopolis and Shoshone. They housed the workers who built the original Boysen Dam in 1908.

Smith acquired and rebuilt the structures to accommodate more customers and offer myriad ways they could spend their money. The Dam Bar opened for business in 1947.

At first sight, it looked like any other highway rest stop. The Bar Café served meals to locals and tourists, who could also buy gasoline and groceries there. Dorothy said the buildings must’ve been deceptively large for the area.

“I stare at that place, wondering how they had a huge café, a huge bar and an outhouse all in that area,” she said. “I think must have been built into the hillside, but I’ve never seen a picture of (the buildings) from the back.”

When the original Boysen Dam was removed and construction on a new dam started in 1948, Smith was ready to cash the checks of the workers building it. King said his uncle worked at a Thermopolis bank and made a cash run to the Dam Bar every week for this purpose.

“They had housing by the lake and couldn’t make it into town to cash their checks, so Barney would cash them at the bar. I’m sure they stayed around and had a drink or two afterward,” he said.

The business was seemingly nothing out of the ordinary. However, locals knew the Dam Bar and Privy for what it really was: “The best damn bar by a dam site.”

Cashing In

During the heyday of the Dam Bar and Privy, it was well-known that anyone who wanted to find a game of chance could “go to the tunnels” at the southern end of the Wind River Canyon. This was a constant irritant for local law enforcement, covered by the Thermopolis Independent Record in a 1948 story headlined “Gambling Stopped in the Canyon.”

Smith wasn’t deterred by the heavy hand of local law enforcement. The Dam Bar’s amenities included a pool hall, poker games and slot machines.

Smith was long suspected of hosting a high-stakes poker game at the Dam Bar and a gambling hall he built on the Adel Homestead, located inside the Wind River Canyon in Hot Springs County.

None of this was legal, but who would tell and ruin all the fun? And even if someone did, Smith had an ace up his sleeve.

Whenever the Fremont County Sheriff came to raid the Dam Bar, Smith moved the poker games and slot machines across the county line to Hot Springs County to the Adel Homestead. And when the Hot Springs County Sheriff came to raid that gambling hall, he moved everything back across the county line to Fremont County and the Dam Bar.

Smith was never caught in the act, nor did he face any gambling charges. Nearly everybody saw him as an honorable businessman.

One account from a Thermopolis resident recalled Smith as “a good neighbor and created much humor around the area. We always wondered where he stashed the cash to keep from paying taxes.”

“Some of our biggest businessmen would be seen today as crooks, but (back then) people looked the other way because they were good for business,” Dorothy said.

King said Smith found another lucrative enterprise he operated from his home in the canyon.

“He had a whiskey still in his Wind River Canyon gambling hall,” he said. “He’d take the whiskey to the Dam Bar and sell it there.”

King said a tribal elder from the Wind River Reservation confessed they regularly bought whiskey from Smith, often drinking it at his gambling hall before going home.

And then there’s the story of the “setters” and the speaker.

Pointers And Setters

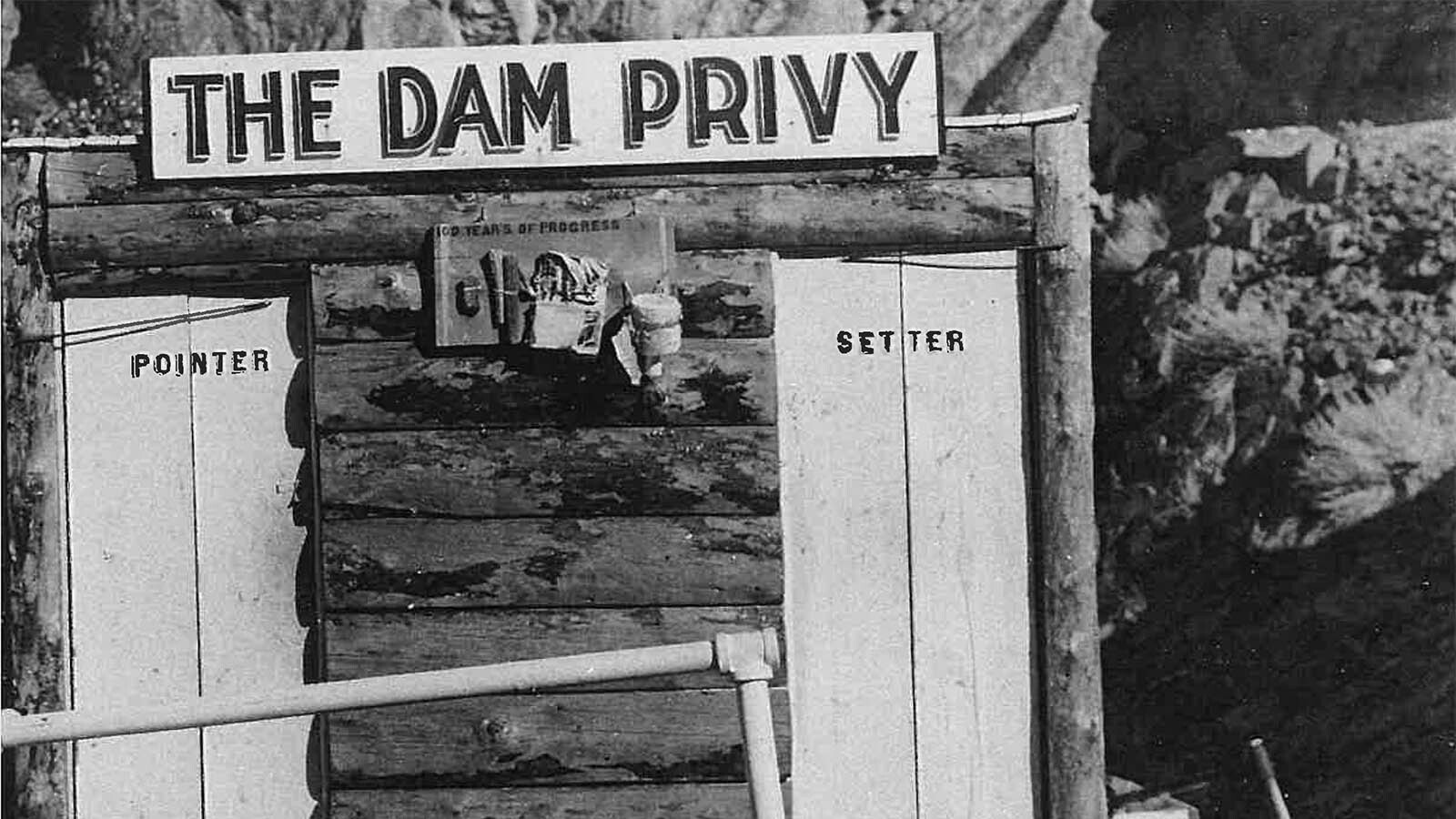

Anyone who needed to use the Dam Bar’s bathroom would have to cross U.S. Highway 20 to reach The Dam Privy, which hung over the Wind River. One was marked “Pointers” and the other “Setters,” designating their use by respective genders.

Even here, Smith had an enterprising way to engage in skullduggery.

“He ran a speaker wire from inside the bar, underneath the highway, to the outhouse,” King said. “He had a microphone in the bar. When a lady would stop and use the facilities, he’d pick up the microphone and say something like, ‘Hey, I’m working down here!’ And they’d almost always get in their car and drive away.”

It’s more than an urban legend. King said several accounts of this prank have been verified, and eyewitnesses have attested to seeing it happen — the speaker was located on the wall beneath the toilet seat.

In the 2000s, The Hot Springs County Museum found a poem in its archives. “The Old Gas Station” was a poorly written but accurate chronicle of how Smith operated the scheme that lines up with primary sources from Dam Bar patrons.

Buried Treasure?

The outhouse prank is crazy enough to be true, but there is another urban legend associated with Smith. He made plenty of money through his various enterprises and was very particular about what he did with it.

“Every week, he would come to the bank with his cigar box full of cash and make a deposit,” King said. “He did not trust the banks, so he deposited it in his safe deposit box.”

But Smith only deposited his cash. He never brought his coins to the bank, which started the urban legend of Barney Smith’s buried treasure, a fortune of coins supposedly buried near the Dam Bar.

“Barney never told his wife where he buried the money,” King said. “And only one nephew knew.”

Privy To History

Smith died in 1953 while attending a funeral in Adel, Iowa. His wife ran the Dam Bar for a time after his death, but later sold the property. By then, much of the Dam Bar’s reputation had transitioned to memories and anecdotes.

It’d be only fitting that the Dam Bar and Privy met an infamous end, which it did in August 1963, when the structures were destroyed in a fire. Only the foundations remain, which can still be seen near the Boysen Dam.

“That (fire) was suspicious, too,” King said.

The news of the Dam Bar’s end might have been bad for many, but not everyone. King said a woman from Fort Washakie had told him how much women hated the business.

“She told us, ‘I hated that place. Most women did. Anytime I came around the corner, the place made me sick.’ She knew what went on there,” he said.

King said she had a secret wish fulfilled when she learned of the bar’s destruction.

“She’d always say, ‘I wish that place would just burn down.’ One day, she turned the corner, and it had,” he said.

And for anyone wondering, King said the nephew who knew where Smith’s buried treasure was located died within a year of Smith’s death.

“No one ever found the money,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s true or not, but it makes for a great story.”

For Dorothy, the colorful story of the Dam Bar and Privy adds to the luster of Thermopolis’ Wild West legacy. In many ways, the spirit of those days persisted in the region long after the Old West was relegated to history.

“I don’t think the Wild West left Thermopolis until the 1970s,” she said. “We might still be experiencing a bit of it.”

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.