Ego can prompt many into thinking the universe revolves around them, but for people in Wyoming, that’s true — to an extent.

That’s because North America as we know it basically spun off from the giant stable block of the Earth’s crust that’s under present-day Wyoming. Scientists call that a “craton,” and the one here was the nucleus of a continent.

It’s not an opinion or theory, it’s written in the bedrock foundation that everything in Wyoming stands and was built upon, according to Dr. Ron Frost of the University of Wyoming.

Political and philosophical debates aside, Wyoming is the most stable ground in the United States.

2.5 Billion Years Of Stability

Frost is an emeritus professor at the Department of Geology and Geophysics at UW, and he has a special relationship with the Wyoming craton, as he was one of the geologists who helped discover it.

“When I came out here and started working on geology in 1978, we knew nothing about the Wyoming craton,” he told Cowboy State Daily. “Since that time, we’ve developed ways of dating these rocks, and we found out that Wyoming was a special craton, independent of the rest of North America.”

A craton is a portion of the Earth’s crust that has not been deformed or modified for a significant amount of time. The Wyoming craton was discovered when Frost and others confirmed the age of Wyoming’s rocks and realized how old and unchanged they are.

The crust and continental plates that comprise the North American continent have been remaking themselves for billions of years. Frost said the bedrock of Wyoming has stayed mostly the same throughout all that time.

“Nothing has really happened (in the Wyoming craton) in 2.5 billion years,” he said. “The Wyoming craton is a portion of the Earth’s crust that has been very, very stable for a very long time.”

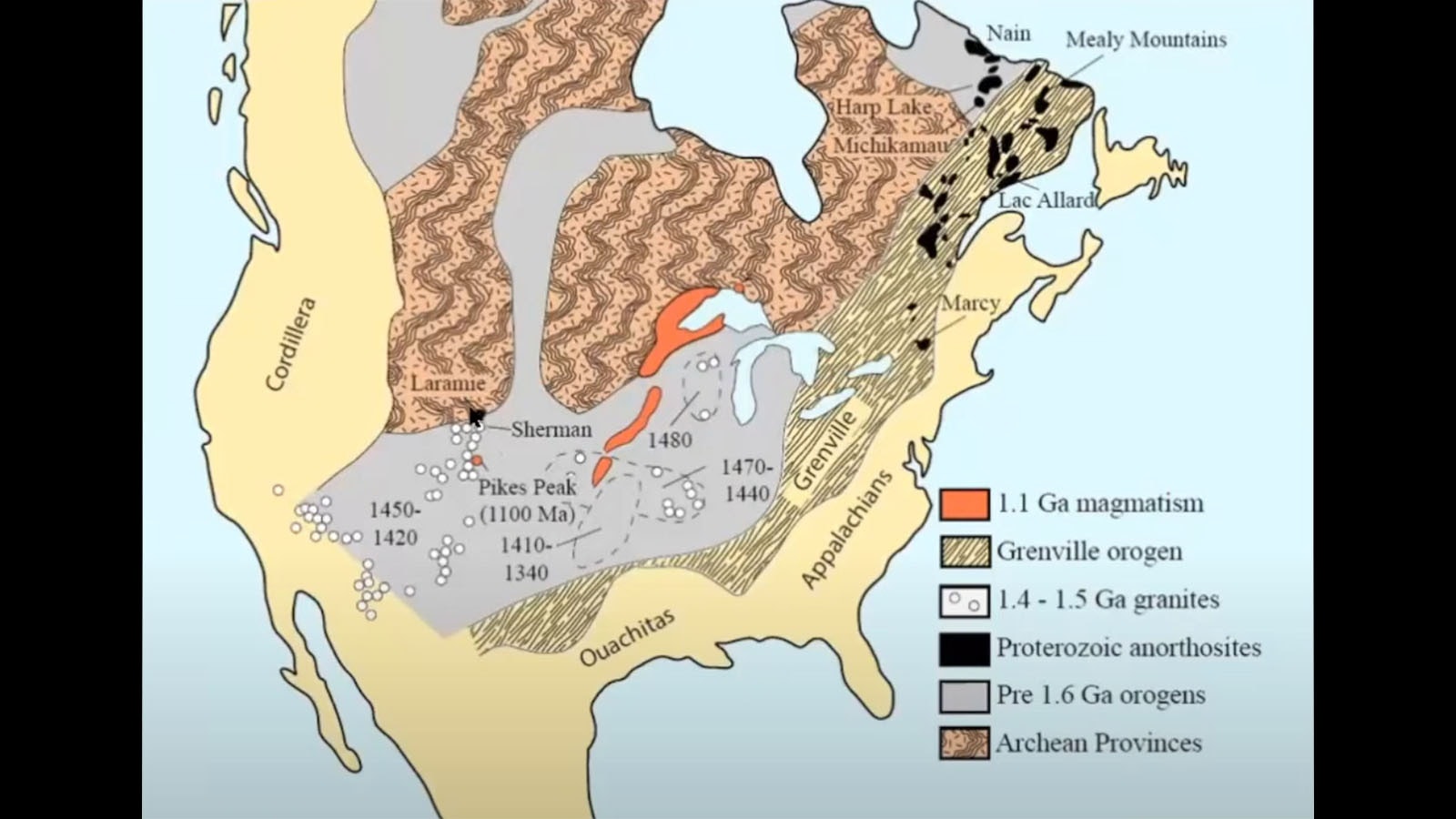

The craton itself is almost entirely contained in Wyoming. Its southern boundary extends along the Medicine Bow Mountains to the Sierra Madre Mountains. The northern boundary extends into parts of western South Dakota and southern Montana, but the vast majority is within the state lines of Wyoming.

“That’s how it got its name,” he said.

How And Why

Identifying the Wyoming craton is one thing. Explaining it is quite another, and the mysteries of it are just as resilient as its unchanging bedrock.

Frost said there’s no consensus on why the section of the planet’s crust under Wyoming has stayed so stable for so long.

“It’s very difficult to answer,” he said. “Was this something that was totally random, or was there something special about the fact these rocks are so old that the mantle beneath them was just rigid enough that deformation never took place? It’s a very interesting mystery that geologists still haven’t solved well.”

The Wyoming craton’s stability is especially interesting, given the hyperactivity that created the Rocky Mountains. Between 75 and 50 million years ago, massive forces inside forced the Rockies through the continental crust to form the rugged terrain of the Rocky Mountain region through what scientists call the Laramide orogeny, or basically a volatile time when the Earth was making mountains.

“I like to say California rudely slammed into Wyoming and brought all these rock layers to the surface,” Frost said.

The Laramide orogeny is why Wyoming’s geologic history is so dramatically displayed in its landscapes. Rocks that would ordinarily be deep underground were lifted onto the surface, including the multibillion-year-old rocks that led to the discovery of the Wyoming craton.

A lot of deformation happened during the Laramide orogeny and continues underneath the surface today. But through the entire dramatic episode, the Wyoming craton remained stable and unchanged.

“The old rocks were brought to the surface when the Rocky Mountains were formed,” he said. “So, you can wander around, look at them, and try to make a story out of them.”

The Yellowstone Intrusion

While the stability of the Wyoming craton is unquestioned, there is one noticeable challenge to that stability: Yellowstone National Park. Wyoming simultaneously contains some of the planet's oldest, most stable sections of crust and one of its largest hotspots, creating some of the planet’s younger rocks.

Hotspots are places in the Earth’s mantle, the layer under the crust, where anomalously hot magma burns through the cooler crust and onto the planet’s surface. Yellowstone and the Hawaiian Islands are excellent examples of active hotspots.

For the last 17 million years, as the Earth’s crust moved over the Yellowstone hotspot, the superheated magma burned its way through. A trail of volcanic fields from the hotspot’s destruction stretches across Oregon, Nevada, Idaho and Montana.

The Yellowstone hotspot’s last eruption happened around 640,000 years ago when it reached the northwestern edge of the Wyoming craton. That eruption created the geothermically active landscapes that became Yellowstone National Park.

“Geologically speaking, the Yellowstone hotspot has just recently started interacting with the Wyoming craton,” Frost said. “The eruptions of the last 2 million years were right on the edge.”

The hotspot has been relatively quiet since, with no significant eruptions. Frost said that’s led to speculation that there may never be another Yellowstone eruption.

Since the multibillion-year-old crust of the Wyoming craton is so different from the younger crust the Yellowstone hotspot melted through, the volcano might be stuck there. Frost said this is “total speculation,” but the Yellowstone supervolcano may have met its match in Wyoming.

If so, Wyomingites can breathe easier that their national park probably won’t go anywhere for at least the next several million years.

Life On The Craton

While a uniquely fascinating spot on the planet’s surface, Frost will admit that the Wyoming craton doesn’t impact most people's day-to-day lives. Despite its deep-rooted stability and resistance to change, the surface geology of Wyoming has changed just as dramatically as anywhere else in the 4.5 billion years of Earth’s history.

What the Wyoming craton continues to do is offer insight into the geology of the planet, and North America in particular. Frost anticipates that the Wyoming craton will become more interesting and important for the upcoming generations of earth scientists.

“The Wyoming craton is less well known than others,” he said. “But science slowly moves. I think as the next generation of studies on the evolution of North America take place, the Wyoming craton will play a pretty important role. It gives us a better view of how the old crust was put together. It continues to show us how North America was created.”

The best news for those future scientists is that the Wyoming craton isn’t going anywhere. For the last 2.5 billion years, the bedrock of Wyoming has determinedly stuck to its own ways while the world spins off and changes around it.

Andrew Rossi can be reached at arossi@cowboystatedaily.com.