CHEYENNE — One of the more interesting relics of a bygone era at the Atlas Theatre in Cheyenne is its old-fashioned ad-drop curtain made of asbestos which is still in use in the theater today.

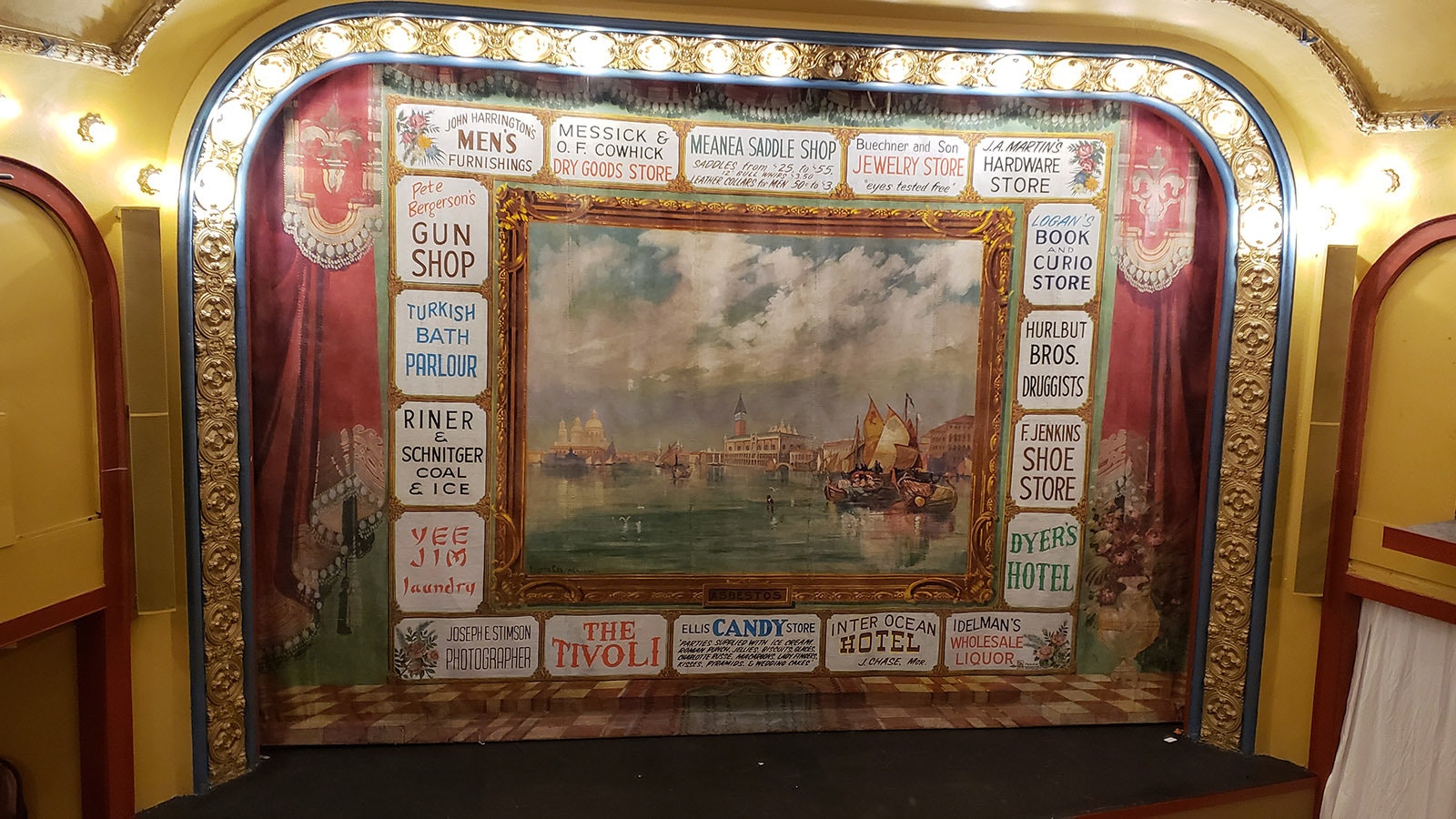

Unfurled, the curtain shows an inviting scene from Venice, bordered with advertisements form early 1900s businesses in Cheyenne.

The curtain’s central image is an inviting scene from Venice, complete with boats floating idly by while seagulls soar and dip on the water’s surface. In the distance, the Venetian skyline beckons, inviting the eye deeper into the painting, deeper into a place of imagination.

What’s surrounding the painting, though, is even more interesting than fluffy clouds floating over Venice. It’s a solid collection of ads — all of them the one-time supporters of art and culture in Cheyenne’s early days.

Of the 18 advertisements painted around the scene, only the Tivoli today survives. But the names of the other businesses alone are quite interesting.

In addition to the Inter Ocean Hotel, there was a Turkish Bath Parlor in Cheyenne — who knew?

The Tivoli started life in Cheyenne as a saloon. Its ad sits sandwiched between an ad for the Ellis Candy Store located in the Atlas Theatre and an ad for the famous Joseph E. Stimson. He was a Union Pacific photographer who produced hundreds of scenes from Wyoming and The West as part of a campaign to scrub Union Pacific’s image clean of scandals.

The curtain shows the Mean Saddle Shop advertised saddles ranging from a mere $25 to $55 dollars. But there were also bull whips for $3.50 and leather collars for men, 50 cents to $3 — a true bargain.

Buechner and Son’s Jewelry store, though, offered to test one’s eyes for free, an even better deal.

Other businesses advertised on the curtain included the F. Jenkins Shoe Store, Dyer’s Hotel, Yee Jim’s Laundry, Riner & Schnitger Coal & Ice, Pete Bergerson’s Gun Shop and John Harrington’s Men’s furnishings.

Messick & O.F. Cowhick’s Dry Goods Store, J.A. Martin’s Hardware Store, Logan’s Book and Curio Shop, Hurlbut Bros. Druggists, and Idelman’s Wholesale Liquor rounded out the list of prominent turn-of-the-century businesses determined to do their part to help elevate the senses in Cheyenne.

A Fast-Disappearing Slice Of American History

The Friends of the Atlas Theatre spent $30,000 to restore the theater’s asbestos curtain with the same company that restored the State Capitol dome in Cheyenne. The curtain had become so dirty over the years, the three-dimensional quality of the brick steps at the bottom of the curtain could no longer even be seen.

While there are hundreds of these drop-down asbestos curtains in, they are a fast-disappearing piece of American history, according to Minnesota art historian Wendy Rae Waszut-Barrett. Few places are choosing to have them restored because of the high cost involved, and many of them are not in the best of conditions.

Waszut-Barrett had the chance to view the Atlas Theatre’s curtain in 2018. She was promoting a book she’d written about the Santa Fe Scottish Rite. As part of that, she took a whirlwind tour of historic theaters in the West, including Cheyenne’s Atlas Theatre.

Waszut-Barrett was interested in the Atlas Theatre in part because she has particularly studied the artist behind the Atlas Theatre’s cool curtain. His name was Eugene Cox, and he was quite famous across the country for his work on ad-drop curtains just like the one in Cheyenne.

“Scenic artists back then could just rake in the profits,” Waszut-Barrett told Cowboy State Daily. “There was a real perceived value for what they brought, and this was at a time when the demand for painted scenery outweighed the supply of artists to deliver it.”

Having such a high-profile artist do its scenic ad-drop curtain would have been a feather in the cap for Cheyenne’s growing arts and culture scene — and an addition very much in keeping with its moniker, the Magic City on the Plains.

Eugene Cox himself did do the curtain, Waszut-Barrett added, which makes the curtain even more significant.

“There’s no question, you know, that someone else did this,” she said. “It’s Eugene Cox. It says Eugene Cox on the back.” If it had just been artists employed by the company, the signature stamp would have said Eugene Cox Studios instead.

“So this wasn’t filled with dozens and dozens of people,” Waszut-Barrett said. “This is his painting. This is a large-scale artwork by a nationally ranked artist.”

Artists Were Big Stars Too

Artists were a really big deal in the theater world at that time, and were often billed alongside even the biggest stars, Waszut-Barrett said.

“There’s like this golden age of scenic art in North America, where the visual artists are on par with the performance artists,” she said.” So, it’d be like so and so is performing and all new scenery is being provided by …”

Cox was one of three brothers who had all made a name for themselves nationwide, with beautiful dropdown curtains across the land in communities both large and small.

“These were people who understood the stage machinery and painted illusion and just the mechanics and the lighting that go with it,” Waszut-Barrett told Cowboy State Daily. “And this is a little bit different because it’s an asbestos curtain, but painted scenery in general is, it’s metamorphic on stage. It’s not just this beautiful thing that hangs on a wall and has one type of lighting on it. They’re meant to transition, to go from dawn until dusk, and bring out colors and reveals. So, this visual aspect of a production would rival the performance aspect.”

Part Of A Larger Business Model

The curtains, in addition to being a fool-the-eye visual experience, were part of a larger business model, one that very much worked in the theater’s favor.

“Scenic companies like Eugene Cox, who did this one, would go and they would collect payment for the ads and that would pay for the production of the curtain,” Waszut-Barrett said. “They would also come in, and they would not only deliver ad curtains, they would do private murals for residences or commercial endeavors.”

The curtain company could also do things like scotch guard the theater’s carpets and other add-on services like that.

Ad-drop curtains typically were not a one-and-done type of service, either.

“It would be a stream of revenue for either the curtain company that produced it, or the theater, depending on what the financial arrangements were,” Waszut-Barrett said.

Ad spaces around the center scene didn’t necessarily stay the same, either. They were a rental, and if a company decided to stop renting that space, it could be painted over with a new sponsor.

“You can see what was previously underneath as the curtains start to age,” Waszut-Barrett said. “It’s very cool. It’s like a history of the town. So, you can look at an ad-drop curtain as a kind of time capsule, because you’re able to see at what point those ads stopped being sold. It’s a whole history of the community that’s wrapped up in a single painting.”

Why Venice In Cheyenne?

Scenes from Venice were something of a fad for the day, and such scenes appeared all over the country, Waszut-Barrett said.

“Before the 20th century, there was a look back to the old world,” she said. “Let’s say you were in some place that hailed from English Heritage. You’d look back at Old English scenes.”

The exception, though, was Venetian scenes. These were universally popular all over the country at the time, regardless of any particular heritage an area claimed.

Beneath the Atlas Theatre’s scene from Venice, the painted word “Asbestos” is prominently displayed. That was all about safety, though it may be strange to think of asbestos and safety in the same sentence today.

But there’s a story behind that which harks back to the infamous Iroquois Theatre Fire in Chicago, where mob bosses had cut corners on key safety features for a theater that could seat around 1,700 people.

When the curtain at the Iroquois inevitably caught fire in 1903 during a matinee — theaters of the day were often lit with kerosene lanterns after all — hundreds of parents with their children were trapped inside a burning theater and couldn’t escape.

“So you had parents who were enraged and sought legislation” to improve the safety of theaters across the nation, Waszut-Barrett said.

Opening just five years after the infamous Iroquois fire in Chicago, the Atlas Theatre owners needed a way to communicate that their theater was safe for patrons, Atlas Theatre tour guides Bill Blansfield and Kelly Douglas told Cowboy State Daily.

“Cheyenne would have heard about that,” Douglas said. “It was in all the papers. So, five years later, if you’re opening a theater, you’d better have something that says we’re safe.”

The word “asbestos,” so prominently displayed, helped advertise the idea to theater patrons that if there was a fire, the ad-drop curtain would fall down to help smother any flames and protect the theater’s patrons, ensuring that everyone could get out safely.

The Atlas Theatre curtain’s asbestos these days is no longer needed to put out fires, but it is still quite safe. The asbestos is all encapsulated by paint, so there is no danger of anything that would cause any health issues.

Renée Jean can be reached at renee@cowboystatedaily.com.