Recent controversy over who exactly made the first summit of Grand Teton in western Wyoming has cast credible doubt on the current attribution — William O. Owen, Franklin Spalding, along with ranch hands Frank Petersen and John Shive — and spurred more research on alternate claims.

At least two others may have summitted the famed peak as early as 1872, predating the accepted and proven claim of Spalding and company by 26 years. The problem is, only Spalding’s group thought to leave physical evidence.

To be really nitpicky, all climbs made by Euro-American explorers are hardly firsts. Native American peoples like the Shoshone, Blackfeet, Gros Ventre and Crow tribes certainly scaled the Grand and left evidence of such accomplishments that exists even today.

Longtime NPS ranger and climbing legend Renny Jackson called the dispute over who made the first ascent of Grand Teton “the greatest of all American mountaineering controversies.”

Owen-Spalding Led The Way

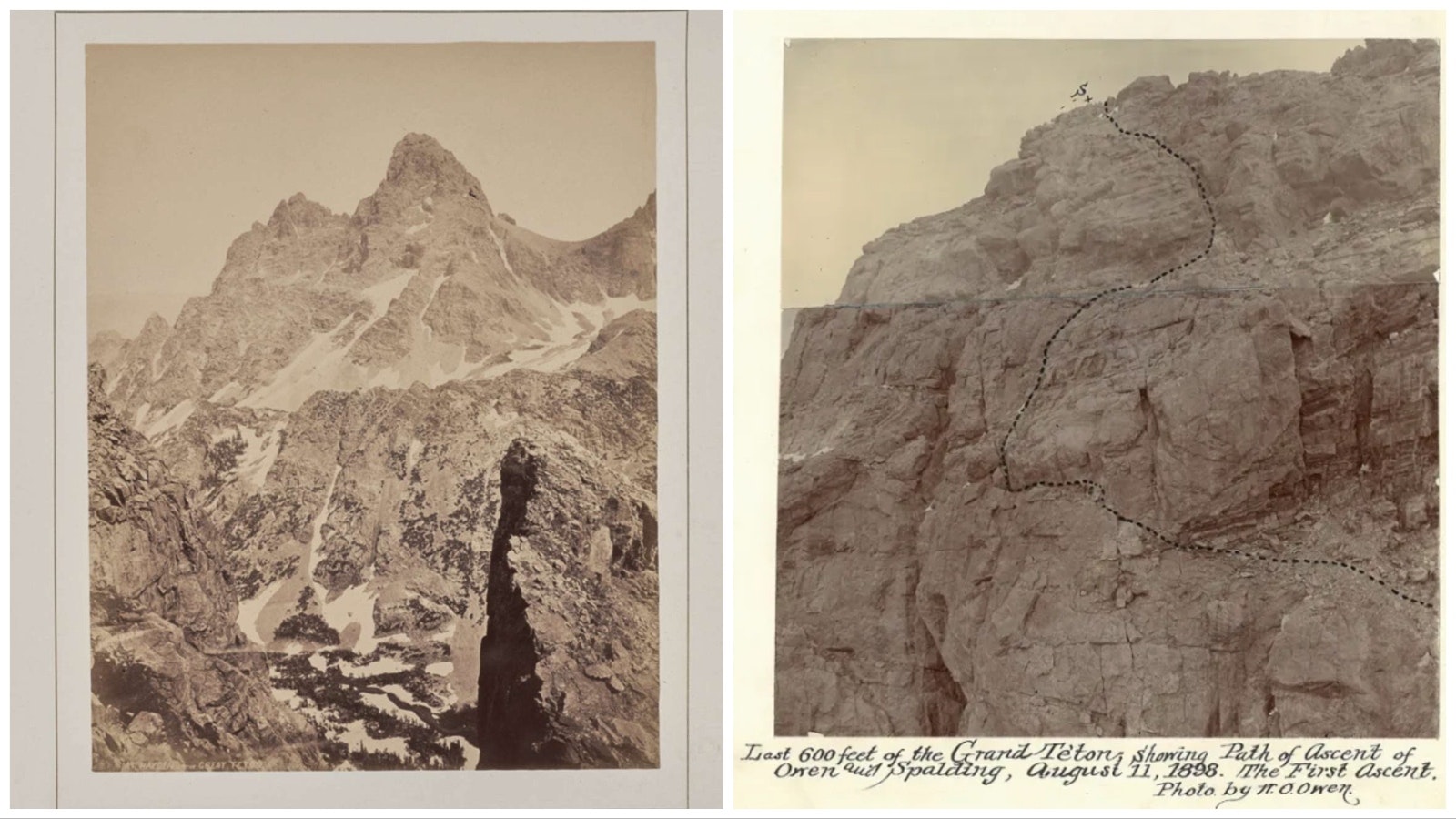

For decades, no one really questioned it was the Owen-Spalding group that summitted the Grand first Aug. 11, 1898. The four-member party was sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Club (RMC), a Denver-based organization established just two years prior.

The climb was so iconic that their documented route is named after them (Owen-Spalding) and is still heavily used with minor variations. Features like the “Chimney” and “Belly Roll” were nomenclature of Owen’s and still used by modern-day climbing guides.

A lot of the acceptance was due to the state of mountaineering at that time. In the late 1800s, climbing for sport was not yet a thing but for a sliver of a niche of hardcore outdoorspeople. Alpinism was in its infancy.

Therefore, no one really thought to include incontrovertible proof along with their exploits.

‘Peak Bagging’

The origin of mountaineering itself really did not begin until early exploration of the American West. Sorry, Appalachians, Adirondacks, et al. After leaving behind Eastern “hills” and traversing the Great Plains, explorers were legitimately floored when they first laid eyes on the towering Rockies.

Real mountains.

Still, the idea of climbing any of the peaks was largely for surveying and mapmaking purposes. The first known ascent of any major feature in North America was made by Maj. Stephen Long of the U.S. Topographical Engineers when he scaled Pikes Peak (14,115 feet) in Colorado during the summer of 1820. That was just to take a reading.

But when the Owen-Spalding party climbed the Grand, it was for the sole intent of saying they climbed the Grand. It was all about bragging rights from the start as “peak bagging” was just beginning to be important to various climbing clubs like RMC.

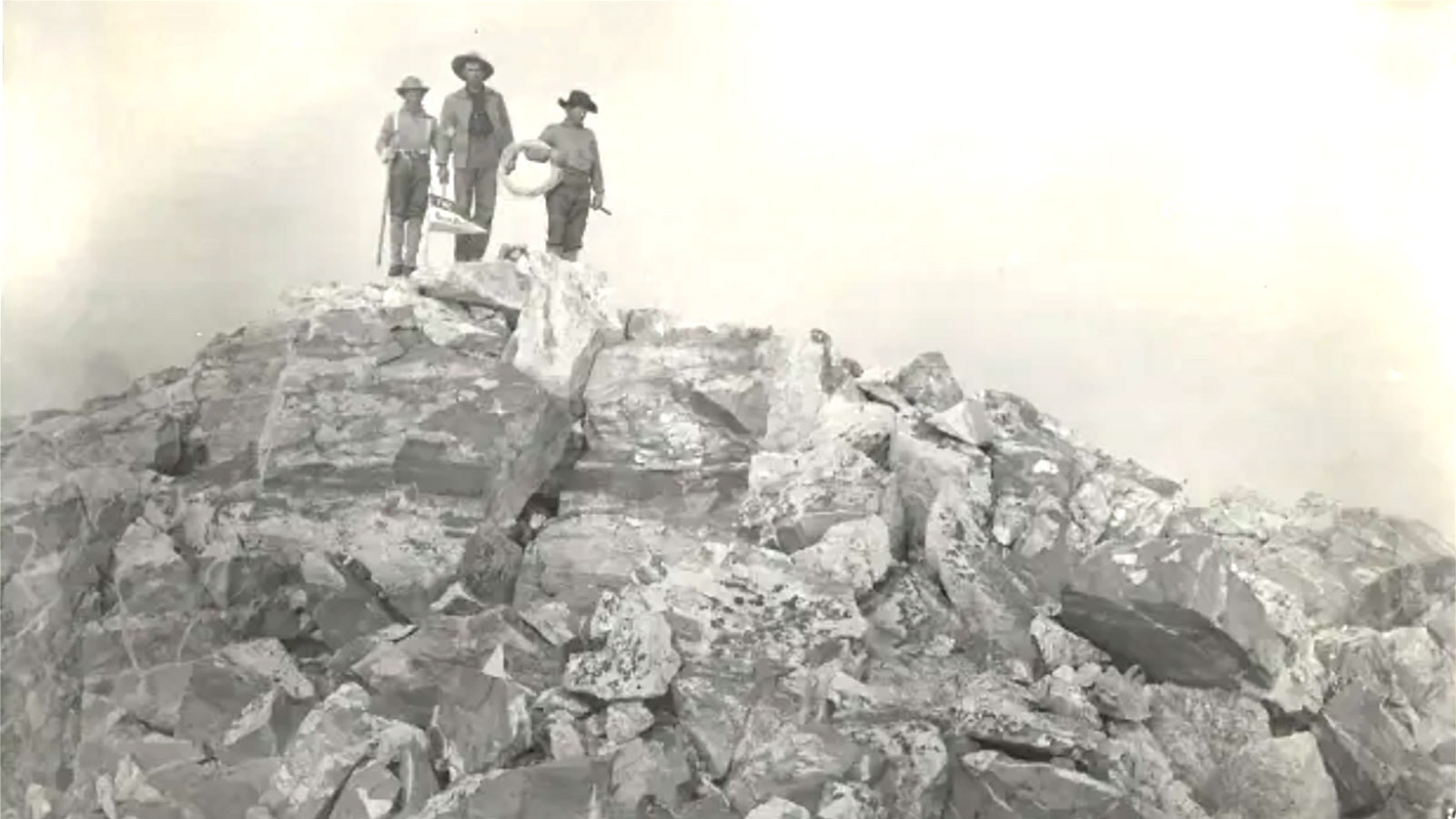

The group took care to grab selfies from the top, leave a sign as physical evidence, and otherwise carefully document the whole expedition. (Actually, they forgot a camera and had to climb the Grand a second time days later to get the photos.)

Gov. Makes It ‘Official’

Owen himself is mostly to be credited for putting his name in record books. In 1898, the 40-year-old Laramie native was nearing the end of his four-year term as state auditor.

Owen was not only a longtime land surveyor, but an avid outdoorsman and occasional writer who had published magazine pieces about his exploits, including an account of riding his Columbia high-wheel bicycle across Yellowstone National Park. A first, he claimed.

Owen went so far as to pester the Wyoming Legislature to recognize his efforts as part of a 30-year self-promotional campaign he spearheaded that included numerous newspaper interviews.

His place in history was firmly established in 1929 when Gov. Frank Emerson signed a proclamation confirming his party the first ascenders of the Grand. Owen immediately went out and bought his own brass plaque memorializing the achievement and had a couple of park rangers affix it on the summit July 30 of that same year, one day after the dedication of Grand Teton National Park itself.

The plaque mysteriously disappeared in 1977, perhaps as backlash to Owen’s claims. Trouble was just beginning to brew.

Other Firsts: What About Kieffer?

Moving in chronological reverse, let’s take a look at plausible summits of Grand Teton that would predate Owen’s. Keep in mind that Owen himself made several failed attempts to reach the top beginning in 1891.

Some historians have found credibility in the notion that a Capt. Charles Kieffer could have summitted the Grand in 1893, sometime around Sept.10. Kieffer, in fact, said such in a letter written to Owen dated April 3, 1899.

Kieffer, no doubt, had heard of Owen’s claim to be first and took umbrage with that. In the letter, the Army surgeon described in detail his route made with two other enlisted men — later identified as Pvts. Logan Newell and John Rhyan — during a hunting trip while the trio was on leave.

Owen kept the correspondence to himself, telling no one, and the letter was only fairly recently discovered in 1959, and subsequently published in O.H. and L.G. Bonney’s 1970 “Guide to the Wyoming Mountains and Wilderness Areas.”

Military records confirm Kieffer was indeed on leave from Fort Yellowstone near Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park where he was stationed. Kieffer stated he made attempts to get his Army buddies to corroborate the claim, but they had mustered out of the service and could not be located.

Kieffer also said he returned to the Tetons the following summer and tried again to summit the Grand but couldn’t because he found a critical snowfield used in his 1893 ascent had melted.

This fact would help verify his claim as the route described by Kieffer is considered today to be an extremely technical climb of an exposed ridge not attempted or successfully achieved until mountaineering pioneer Glenn Exum did it in 1931.

Kieffer could theoretically have only done it in 1893 if he used snow to establish his footing. His admission that once the snowfield had melted out his later efforts were thwarted would check out with the fact that route is simply too difficult without ropes and more advanced climbing skills.

Without physical evidence left behind, such as an identifiable rock cairn, there is no way to prove or disprove Kieffer’s claim, Jackson said.

Even Earlier Claim

There also is some reason to believe Nathaniel Langford and James Stevenson made it to the top of Grand Teton on July 29, 1872. That was the year Yellowstone was established as the nation’s first national park, and it was a busy time of exploration in the Jackson Hole area.

Langford and Stevenson were part of the 14-member federal survey team known as the Hayden Expedition.

An 1873 article published in Scribner’s Monthly stated “eleven brave souls” left their camp at the head of the south fork of Teton Creek west of the Continental Divide (in Idaho) and made for the Grand with the intention of summitting.

Four soon turned back. Two more never made it to the lower saddle between Grand Teton and Middle Teton. That left Langford, Stevenson, Frank Bradley and two teenagers — Sidford Hamp and Charles Spencer — to complete the ascent. Bradley quit soon after, then Hamp and Spencer.

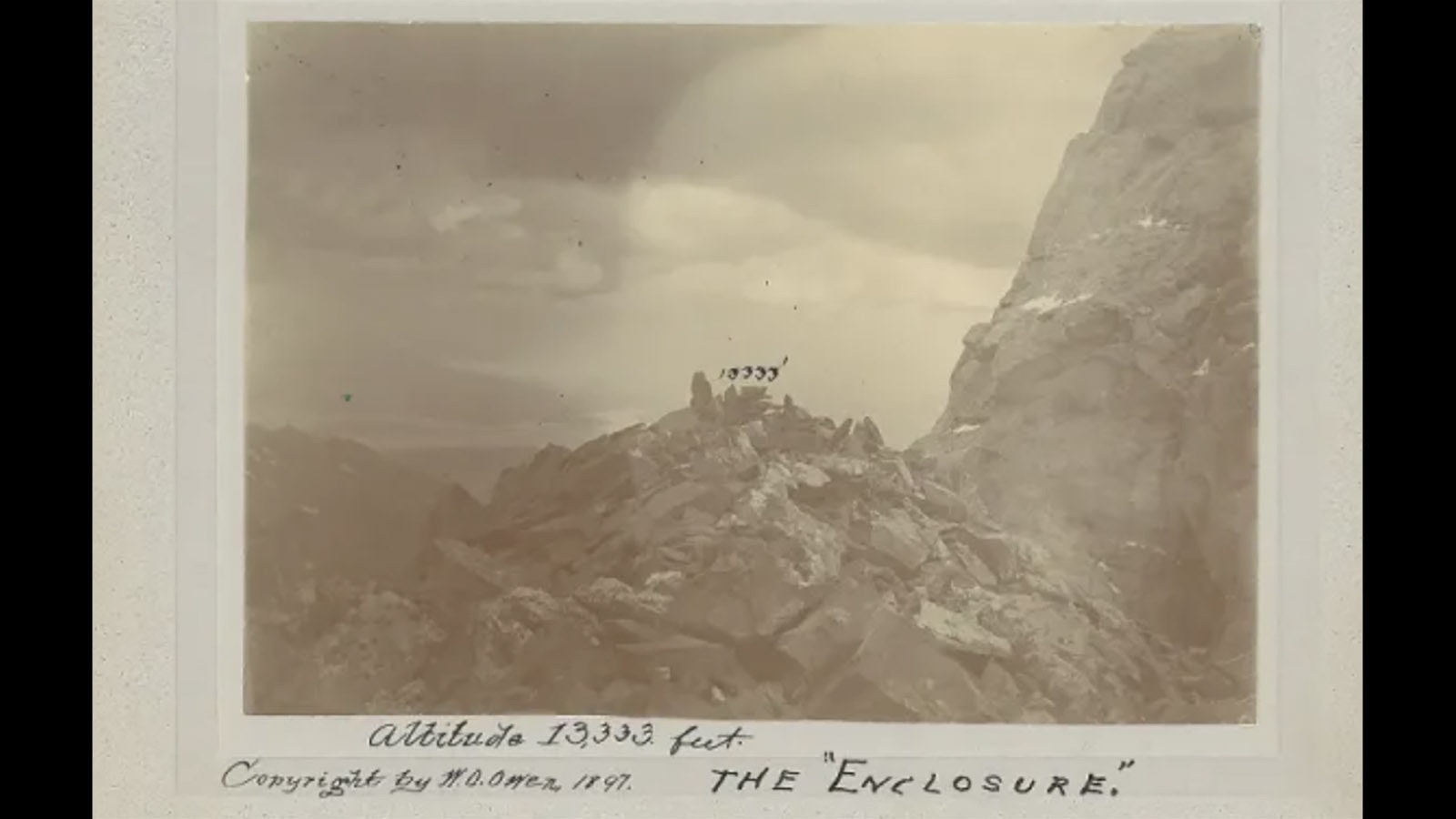

Langford later recounted to Scribner’s: “We found a circular enclosure, six feet in diameter, composed of granite slabs, set up endwise about five feet in height ...”

The Feud Builds

This would confirm Langford and Stevenson made it to at least the Upper Saddle as the unmistakable feature now known as the Enclosure is impossible to miss and thought to be evidence of a spiritual place constructed and used by the Apsáalooke (Crow Indians).

Between the Upper Saddle and the summit, however, is a formidable 100-foot sheer vertical cliff. It, and any other route from there, would require 20th century climbing gear and techniques.

Langford’s descriptions of the climb also become very generalized and vague after the Upper Saddle leading some to believe that’s as far as he actually got. There is no mention, for instance, of particular features or sections of the climb like places referred to by Owen as the “crawl” or the “double chimney.”

Speculation that perhaps, like Kieffer, Langford benefitted from a snowfield helping him through the difficult vertical section to the top has also been scrutinized as photographic evidence from William Henry Jackson (official photographer of the Hayden Expedition), taken within days of days of Langford’s supposed ascent, appears to show a mild winter of 1871-72 as very little snow was seen accumulated on the Grand above the Upper Saddle, especially when contrasted with modern photographs of the area.

A longstanding feud between Langford and Owen played out in front of the public immediately following publication of a full-page article in the New York Herald recounting Owen’s 1898 ascent. Outdoor magazine Forest and Stream in the late 1890s ran a series of back-and-forth articles from the two climbers, each explaining why the other had to be wrong.

Additional mounting evidence against Langford’s claims is the fact that he would have run out of daylight to make the journey as he described it.

“Langford and Stevenson may not have had enough time to do much of anything except to find their way safely down off the peak,” Jackson stated.

Indeed, a recreation of Langford’s trip made by Rick Reese and Jim Fearick in 1998 cast serious doubt on Langford ever reaching the summit. Reese and Fearick duplicated the journey from Teton Creek to the top of the Enclosure and back, taking 13 hours to do so.

Keep in mind, the pair had extensive knowledge of topography and route-finding when they did it. They knew exactly where they were going. They also estimated an additional two hours would have been needed to account for an actual summitting and return from the Enclosure at the Upper Saddle.

A 15-hour journey? Doable, but suspect.

No Less Grand Today

Maybe surprisingly, no one climbed the Grand again for 25 years after Owen and Spalding.

That’s “astonishing,” Jackson said, considering the Tetons were considered a crown jewel in the climbing world and Owen’s account was so well-publicized.

It would not be until the 1920s when the next generation of alpinist legends like Paul Petzoldt and Fritiof Fryxell would begin their famed assaults on the Teton Range.

Petzoldt, incidentally, made his first ascent at the age in 16. He did it in cowboy boots with nothing more than a pocket knife and a can of beans for nourishment. At the time of his death in 1999, Petzoldt had made more than an estimated 300 trips to the top.

Many other firsts have been recognized since, from first woman (Eleanor Davis in 1923) to first Down syndrome (Ducky Harris in 2017).

Today, the Grand is climbed by thousands every summer who use more than 85 routes to the summit.

For more on the controversy over who was first to summit Grand Teton check out “The Grand Controversy” by Helen Thayer.

Jake Nichols can be reached at jake@cowboystatedaily.com.